From the Theatre of Death to the Theatre of Pity

A “Phantom Panel” ex Mnemosyne Atlas, Panel 42

edited by the Seminario di Tradizione Classica, coordinated by Monica Centanni and Katia Mazzucco; translation by Elizabeth Thomson

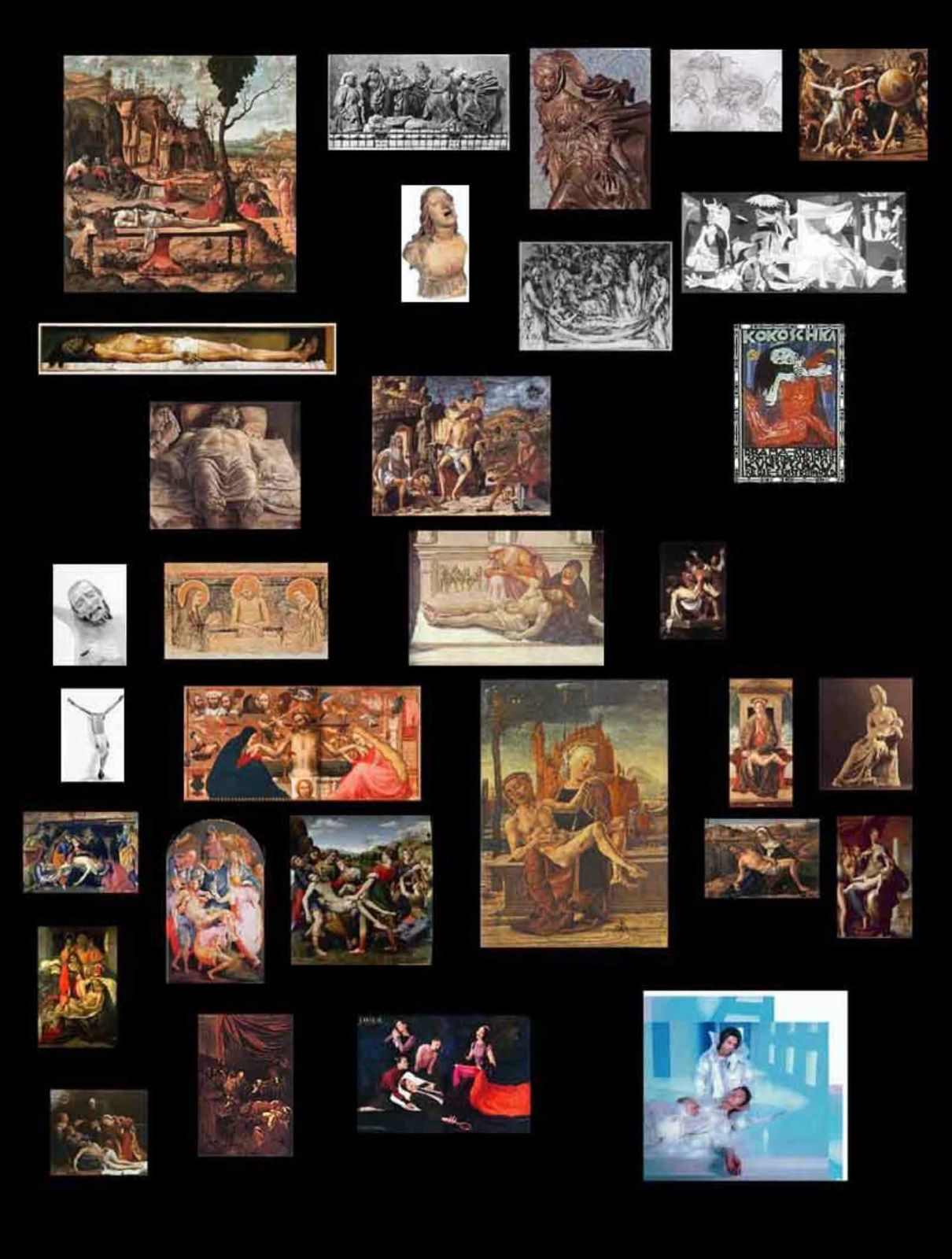

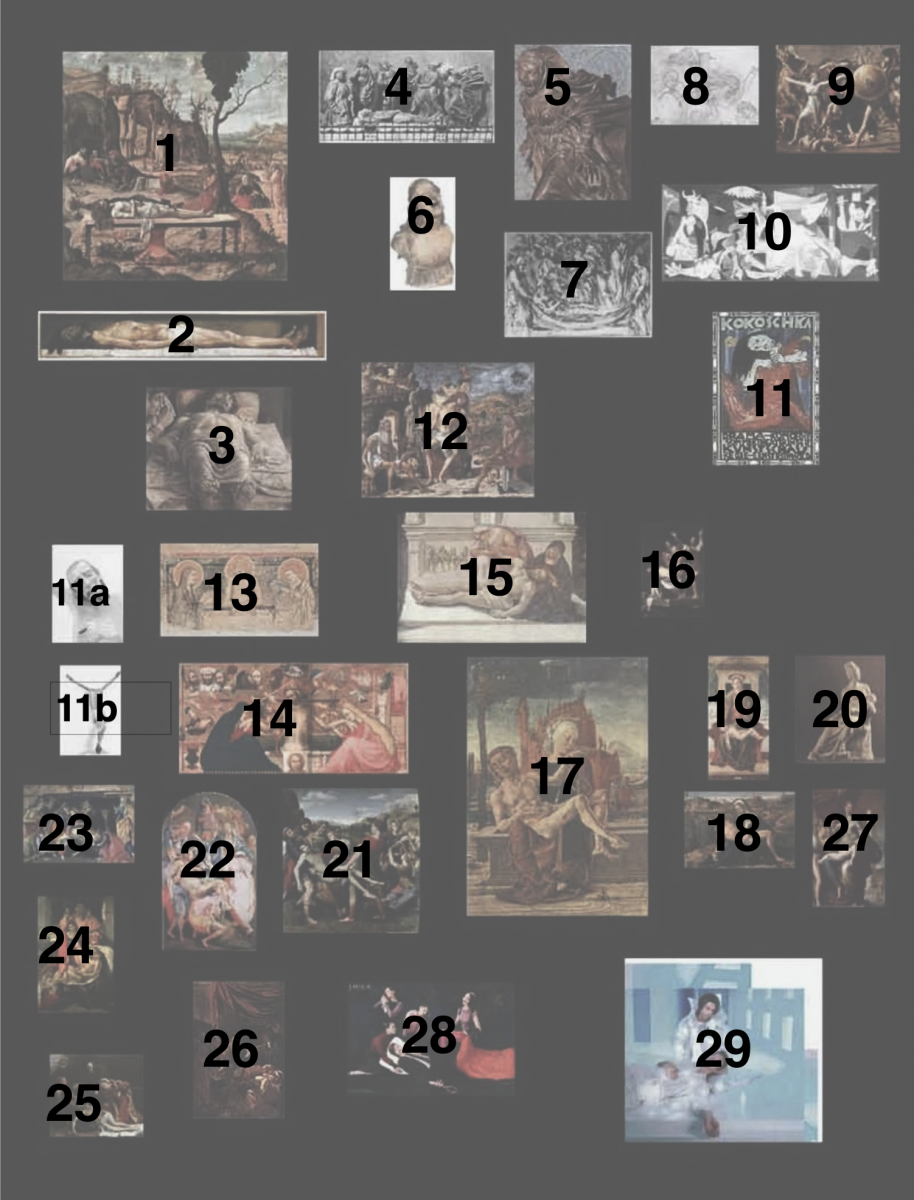

Introduction to creating a Phantom Panel

In accordance with the criteria adopted by Engramma, each of the Mnemosyne panels can be seen to have been created by placing together in multiple groupings of motifs images which are thematically or formally linked by a certain “family resemblance” (Salvatore Settis’ definition). The process of creating each panel gives momentum to a further associative process in the reader by evoking new configurations of images that confirm and develop the ideas identified in the Warburg panels. The outcome of this procedure is called a “Phantom Panel” — from phántasma – and it reflects the images that the interpreter-reader garners by reacting creatively to the hermeneutic stimulus created by the groupings originally assembled by Warburg.

The seminal standing of Warburg’s work is revealed by the fact that the visual hypercourses that can be traced through the panels are not locked in a rigid and finished form; they continually open themselves up to new, and different, trajectories of meaning. Without fixing set itineraries, Warburg placed his images on card, foreseeing the likelihood of moving them around, and allowing them to migrate from one panel to another.

Interpreting and reading the images of a panel, and the newly assembled panel that derives from it, are just one of the many interpretations possible. The diversity of itineraries confirms the value of the interaction between Warburg’s work and the reader-interpreter: unencumbered by preordained threads, s/he is able to shift her/his gaze to identifying archetypal motifs and morphological continuities. As Giorgio Pasquali early on observed, Mnemosyne acts on and reacts to the scholar’s gaze allowing itself to be prolifically transformed into new creative exploration, that in our case have found expression in a “Phantom Panel”.

Guide to the “Phantom Panel” ex Mnemosyne Atlas, Panel 42

1 | Vittore Carpaccio, The Dead Christ, 1520 ca., Berlin, Gemäldegalerie.

2 | Hans Holbein, The Dead Christ in the Tomb, 1521-1522, Basel, Kunstmuseum.

3 | Andrea Mantegna, The Dead Christ, 1478-1480, Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera.

4 | Nicolò dell’Arca, Lamentation over the Dead Christ , 1485 ca. Bologna. Santa Maria della Vita.

5 | Nicolò dell’Arca, Magdalene, detail from Lamentation over the Dead Christ, 1485 ca. Bologna. Santa Maria della Vita.

6 | Guido Mazzoni, Complaining Woman, 1485-1489, fragment from Compianto su Cristo morto, dalla Chiesa di Sant’Antonio di Castello a Venezia, Musei Civici di Padova.

7 | Baccio Bandinelli’s Workshop, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (detail), mid-16th cent, Firenze, Museo Horne

8 | Jacques-Louis David, Draft for The Sabine Women, 1795-1799, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

9 | Jacques-Louis David, The intervention of the Sabine Women (detail), 1799, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

10 | Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

11 | Oscar Kokoshka, Imago pietatis (Murder, Hope of Woman), poster, Kunstshau 1909, Wien, Österreichische Museum für Angewandte Kunst.

11a | German-Rhine sculptor, Crucifix, detail, 1300-1315, Pisa, Chiesa di San Giorgio dei Tedeschi.

11b | German-Rhine sculptor, Crucifix, 1300-1315, Pisa, Chiesa di San Giorgio dei Tedeschi.

12 | Vittore Carpaccio, The Meditation on the Passion, 1510, New York, Metropolitan Museum.

13| Anonymus, Resurection, XIII-XIV secolo, Venosa (PZ), Chiesa della Santissima Trinità.

14 | Master of the Straus Madonna, Piety with Mary and Magdalene, 1400 ca., Firenze, Gallerie dell’Accademia.

15 | Luca Signorelli, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, detail, 1499- 1502, Orvieto, Duomo, Chapel of San Brizio.

16 | Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, 1602-1604, Roma, Pinacoteca Vaticana.

17 | Cosmè Tura, Pietà, 1470-1480, Venezia, Museo Correr.

18 | Giovanni Bellini, Virgin Enthroned Adoring the Sleeping Child, 1475, Venezia, Gallerie dell’Accademia.

19 | Giovanni Bellini, Pietà, 1505, Venezia, Gallerie dell’Accademia.

20 | Mater Matuta, II sec. a.C., Capua, Museo campano.

21 | Raffaello, The Deposition, 1507, Roma, Galleria Borghese.

22 | Pontomo, The Deposition, 1526 ca., Firenze, Chiesa di Santa Felicita.

23 | Sandro Botticelli, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, 1495, München, Alte Pinakothek.

24 | Sandro Botticelli, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, 1490 ca., Milano, Museo Poldi Pezzoli.

25 | Annibale Carracci, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, 1604-1606, London, National Gallery.

26 | Caravaggio, Death of the Virgin, 1604-1606, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

27 | Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck, 1534-1540, Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi.

28 | Death of the Dandy, advertising campaign for a clothing brand, November 2000.

29 | David Bowie, “Auto-pietà”, cover image of Hours, 1999, Virgin Record America (photo by Tim Bret-Day).

The “Phantom Panel” derived from Panel 42 of the Mnemosyne Atlas. This composition begins with the closing image of Panel 42 [Fig. 1] and continues re-using and developing the thematic strands contained within it. In the theatre of death of Panel 42, the tension between the polarities of masculine and feminine, life and death, stasis and movement are emphasised by means of a series of Renaissance images that are brought together. On the one hand the images confirm these polarities by their uniquely strong lines, and on the other they lead to the break down of the primary tension and to the freezing of gender and role differentiation (mother son, life death, masculine feminine) into the posture of majesty-pietà. (Figs. 17, 18, 19, 20, 27, 29). In this way, a different thematic itinerary develops out of the chronologically and thematically compact grid of Warburg’s composition, and it culminates in the final image with a further complication in meaning.

In Carpaccio’s Lament over the dead Christ [Fig. 1], the closing image of Panel 42 and the opening image of the “Phanton Panel”, three themes revealing itineraries of meaning come to light: death, grief, and contemplation of death. The principal theme is death: one is struck by the deserted landscape and the serene expression on the face of the dead Christ resting on his funeral bed in the foreground of the painting, by the composure and position of his hands, factors that despite the visible bleeding wound in his ribs and the hole made by the nail hammered into his right foot, seem to express the notion of death as a peaceful slumber. Mary Magdalene and John, to the right of Christ, express grief in the face of death, a grief that is silent and contained; Mary is almost lifeless, and supported by Mary Magdalene, her face completely in shade and turned upward toward heaven. The figure of Job, closely associated with the body of Christ, almost forming part of it, is positioned, it would seem, between the green cloak and the feet of Christ. Job introduces the theme of contemplation on the mystery of the death of Christ. His face expresses anxiety, but it also expresses awareness of the inevitability of his sacrifice.

The tension between the polarities of masculine-feminine, life-death, and stasis-movement, evoked in Carpaccio’s composition finds release in the image of the dead Christ on the one hand, and the intensity of the grief manifested by the grieving women [Figs. 4, 5, 6] on the other.

The figure of Holbein’s Christ in his tomb [Fig. 2] is the manifestation of death’s finality. The rigidity of his grey emaciated limbs, the contraction of his right hand, the spasm in his face, and his fixed gaze, are amplified by the complete isolation of the figure which is locked and squeezed into the narrow space, removed from the suffering of the outside world. The body of man-god is forced into the restricted space of the picture-sarcophagus and his carnality is more than real; the abstract silence of the tightly enclosed space speaks of the all too human horror of death, and communicates the impression of desolate death as the exhaustion of all vital energy and capacity for grieving. In Mantegna’s Dead Christ [Fig. 3], Christ’s humanity is portrayed differently. His body laid out in an enclosed space, seen frontally, displays the holes left by the nails hammered into his hands and feet; by his side, Mary and John display their profound grief; but compared with the isolation and total seclusion expressed differently in Carpaccio’s deserted landscape, and the dark airless space of Holbein’s sarcophagus, Mantegna’s two grieving figures inspire a circular sequence of pathos, although this is marginal.

Reasserting the two principal hermeneutic perspectives of Panel 42, the impetus of the grieving women also functions as a counterpoint to the deathly motionlessness of Christ the man in the upper border of this composition.

In Niccolò dall’Arca’s Pietà, grief for Christ’s death is the dominant theme [Fig. 4]; the overwhelming grief of the female figures is communicated by their contorted bodies and their quivering garments in the conventional emotive formulas of despair. The climax is reached in the figure to the right — the Mother — whose dramatic entrance into the scene with arms stretched behind her evolves, in an almost circular fashion, into the movement of her garment in an unrestrained eruption of potent pathos.

The howling grief [Fig. 5] of Niccolò dell’Arca’s Pietà is transformed into exhaustion and grief in Guido Massoni’s Pietà [Fig. 6], which represents a moment in the process of internalising the grief that reaches a climax in the veiled figure in Baccio Bandinelli’s Lament over the Body of Christ (Fig. 7 ex Fig. 42.14).

Various other perspectives branch off from the emotive formula of the rushing figure with arms stretched behind her. From a drawing in which the pathos of a grieving figure can be seen, David takes the posture of the central figure in the The Sabine Women [Fig. 9] where once again the stasis of the masculine figure (in this case the statuary pose of a warrior) is countered by the emphasis of the female figures and their grief, but whose pose is frozen in the neo-classical composition. A further derivation of the emotive formula of pathos can be found in the context of war in Picasso’s Guernica [Fig. 10], and also in the Kokoshka’s Pietà [Fig. 11] in which grief deforms the features and postures of the bodies—postures and bodies deformed by grief as can be seen in the medieval images of Christ and the Crucifixion which were directly modelled on the martyred bodies portrayed in the Via Crucis [Figs. 11a, 11b].

The theme of contemplation of the mystery of the death and resurrection of Christ acts as a link between the two polarities, and is central to Carpaccio’s Contemplation on the Passion of Christ [Fig. 12], a representation of internalised grief (as prefigured in the Veiled figure [Fig. 7]), rationalised and completely immersed in contemplation.

The grieving figures, which represent the humanised pain of Mantegna’s Christ, were a dominant in Venosa’s Lament, both Piety and Resurection. In this case the howling despair isolates the characters in the scene in an irreconcilable way. The body of Christ, his arms folded, lies between Mary, with her eloquent gesture of desperate suppliance, and John, who opens up the garment he is wearing unbearing his chest in grief. Master of Madonna Straus’s Deposition acts as a counterpoint [Fig. 14]: the figure of Christ in the same position (half standing figure exiting from the tomb) holds his arms open in a gesture of binding together in their grief the figures of Mary and Magdalene. The union of the two Marys is sealed with a double kiss as they support the inert arms of the dead Christ.

The kiss of Christ’s hand, an occasion for sharing and accepting their grief, returns as an eloquent gesture in Luca Signorelli’s Lament [Fig. 1] in which Mary Magdalene gathers to her breast the hand of Christ lacerated by the nails of the Crucifixion, whilst Mary supports the head of her son in one hand, and holds the other open to heaven (thereby making another eloquent gesture). In the background of the image, painted en grisaille, appears a scene showing the body of Meleager being carried, an obvious echo, in counterpoint, of the posture of the body in the forefront. In the dialogue between the ancient theme and pathos, resemanticised in the new religious context, a topos of death, typical in Renaissance art, is present: the arm extended alongside the body or hanging, a motif that also reappears in Caravaggio’s Deposition [Fig. 16].

Cosme Tura’s Pietà [Fig. 17] constitutes a thematic and gestural turning-point in the panel: there appears the eloquent gesture of the kiss on the hand, but it opens up a new perspective of meaning and informs the third level of the “Phantom Panel”, a section which is completely original in respect of the themes inspired by Panel 42 of the Atlas, the theme of the Pietà and Majesty. In the representation of Mother and son, Tura synthesises two emblematic images: the ancient figure of Majesty (derived from the icon) and the new iconography of the Pietà. The sensation of this synthesis lies in the representation of the Madonna in majesty sitting on a tomb holding in her arms not the body of a Christ child but the adult body of Christ contracted and diminished by death, and for this very reason eminently capable of being identified with a child. A Pietà of Bellini’s in which the Madonna, disconsolate, holds her dead son in her arms [Fig. 18] is superimposed by a Maestà by Bellini [Fig. 19], in which the prefiguration of death is already consciously rendered in the posture of the sleeping infant abandoned in the lap of his mother with one arm hanging and his little legs crossed. This can be perfectly interchanged with the posture of the dead body now in his mother’s arms. The dogma associated with the incarnation — the death and resurrection of Christ — leads back to the theme of the mother, giver of life and death, a subject that was already established and featured in myth and the cult of Mater Matuta [Fig. 20].

From the synthesised figure of the Pietà and Majesty [Fig. 17], that recalls the theme (Panel 42) of the giver of life and death on the one hand, and on the other the spiritual union sanctioned with a kiss, an itinerary leads via a circular route to the climax of the closing image [Fig. 29] via the phenomenology of death.

It is here that, contrary to the “Theatre of Life and Death” of Panel 42, the gradual dissolution of the polarities between masculinity-stasis-death versus femininity-movement-life occurs: pathos is expressed no longer in opposing tensions; rather, it is the conjunction and confusion between life and death, between the masculine and feminine.

The motif of the bearing of the dead Christ that originates from Raphael’s Deposition [Fig. 21], functions as a feature of narrative unity between the Pietà — where disfiguring grief is reconstituted in the figure of the mother who has accepted her son’s fate — and Pontormo’s Deposition from the Cross [Fig. 22] in which all the figures in the lament scene appear to be drawn from immediately consecutive flash images (compare Magdalene’s progressive approach towards the body of Christ and the sequential movements of the characters in the painting).

In Carracci’s Three Marys [Fig. 25], Mary’s loss of sensibility is fused with her son’s death, a fusion that seems to identify Mary with Christ, and therefore the woman with the man, sanctioned by the common destiny of death, which at the same time is slumber (Dormitio Verginis), and therefore a seeming death, which in Christian theology is a prelude to eternity. The position of the two figures, one superimposed upon the other, the Virgin’s hand resting not on her breast this time, but on her son’s, portrays in their common loss of sensibility, the mirrored reflection of their two identities. Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin [Fig. 26] justifies this identification: death, or Dormition, until this point, the fate of the son against which the grieving mother fought, unites the two protagonists and transfigures them. The interchange of their identities also involves the group of grievers around the corpse, at this moment that of the dead Mary — they are all male figures excepting the grieving female figure in the forefront. Caravaggio’s work acts as a counterpoint for the Pietà by Niccolò dell’Arca.

The assimilation of death-new life is continued in the iconography of Parmigianino’s Madonna enthroned With Child [Fig. 27], a representation of the incarnation and prefiguration of the passion-death-resurrection of Christ. This is a motif that cannot have been drawn from a model; it is retrieved via an engram from the figure of Mater Matuta [Fig. 20]. This mother figure with powers over life and death, by the eloquent gesture of her hand on her breast, can be juxtaposed again with the image of the Pietà.

A contemporary publicity image [Fig. 28] would appear to be a retake from the theatre of Pietà and Death. The body of Christ has been substituted for an obviously ambivalent figure, either a woman or a man, a death that relates without distinction, therefore, to either sex, and to symbolic figures to whom the figures in the Lament and Death relate. The corpse holds in his hand a mirror that as well as being an attribute of vanity is, in the context of our interpretation, a symbol of refracted and illusory identity.

The next image is a Pietà, represented by a double image of David Bowie [Fig. 29] based on the double role of the female figure, the Pietà-Madonna and the masculine figure of Death-Christ.

In the closing image, therefore, the polarities perceived as opposites implode and cancel each other out. Via Death a kind of coincidence of opposites is produced, and is synthesised into one figure — David Bowie’s Pietà — which, for the singularity of its representation (overexposed light that freezes the figures into a statue like fixity) fully expresses the abstract thoughts that have influenced the mentality of this enigmatic individual.

English abstract

In the panel ex Mnemosyne Atlas, Panel 42, that was called “Phantom Panel”, and it’s Warburg’s work, we can see the Theatre of Death’s representation, which comprehends various relationships that are internal to the theme of death; this essay wants to take a trip from the Theatre of Death to the Theatre of Pity, including how those artistic forms, their roles and their internal tensions were used not only during the period of the Renaissance, when we can witness the work of artists like Carpaccio, Mantegna, Tura, Caravaggio and Raphael, but also by modern painters like Picasso and singers like David Bowie. Death and Pity have developed different and intertwined characters, so, what are the relationships between these theaters and their evolution during years? These are the questions that this essay wants to answer.

keywords | Theatre of Death; Theatre of Pity; Mnemosyne Atlas.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Seminario Mnemosyne, From the Theatre of Death to the Theatre of Pity. A Phantom Panel ex Mnemosyne Atlas, Panel 42, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 6, febbraio/marzo 2001, pp. 17-23 | PDF