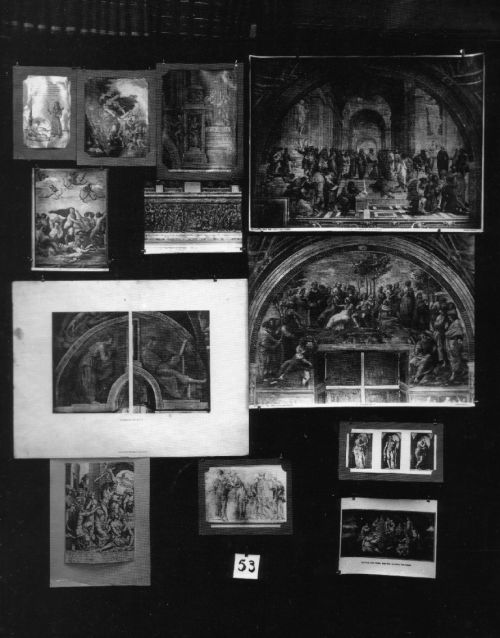

Mnemosyne Atlas’ Panel 53. The Muses

edited by Seminario Mnemosyne, coordinated by Monica Centanni e Katia Mazzucco. Translation by Elizabeth Thomson

English abstract | Versione italiana

Panel 53 | Notes by Warburg & co; details; captions; papers

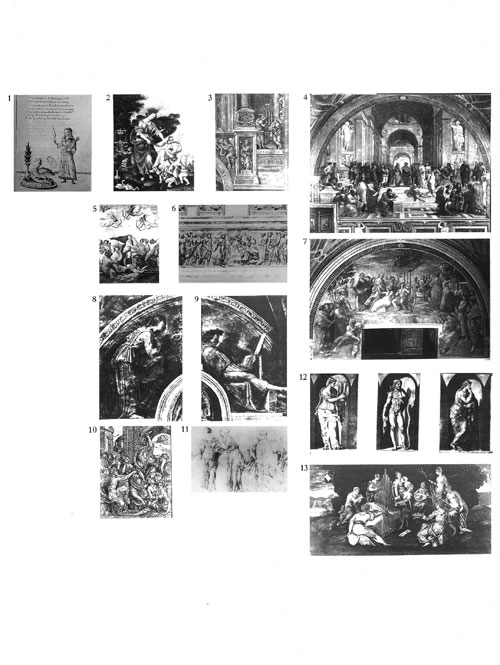

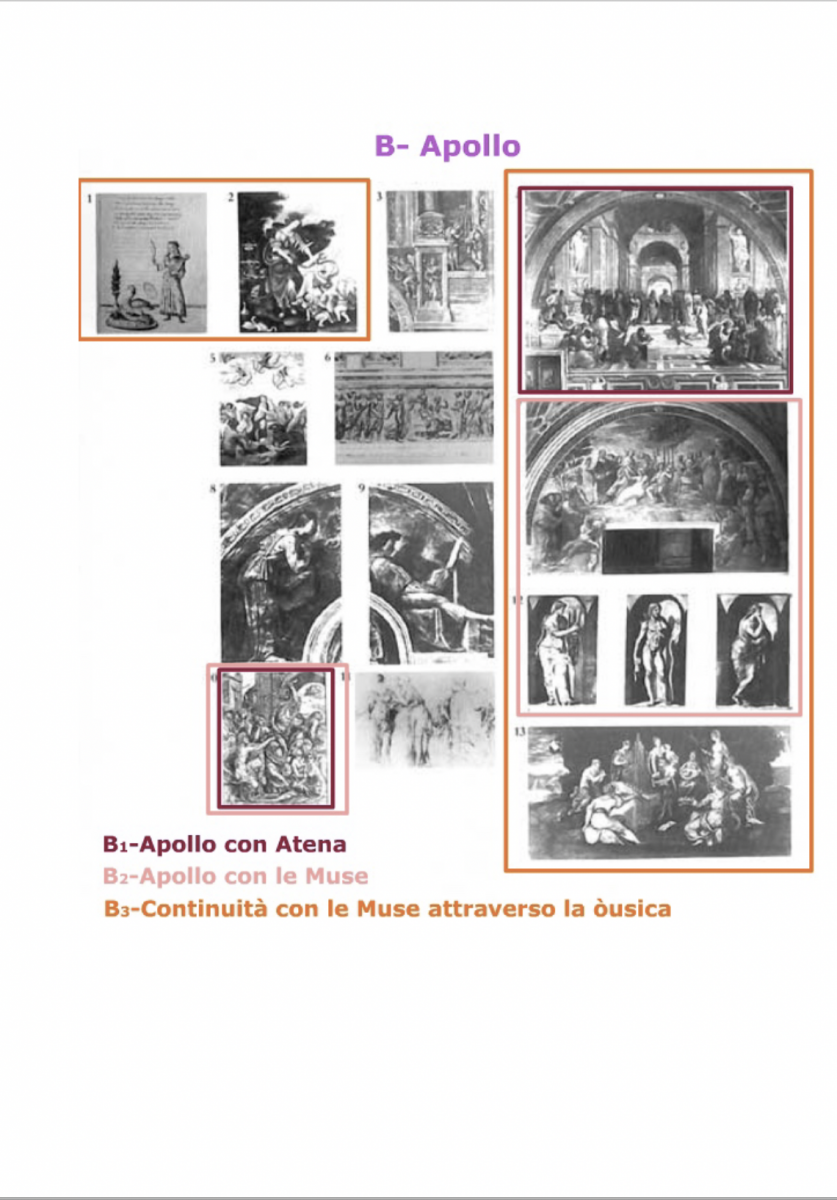

The first and last images of Panel 53 (Figs. 1 and 13 respectively) provide the first and the most explicit guides to finding one’s bearings throughout the entire Panel. Both works, an illumination dated 1476 and a painting by Tintoretto dated 1545, depict the daughters of Mnemosyne.

At the beginning of the Panel, on a page of an illuminated manuscript that describes the marriage of Costanzo Sforza and Camilla of Aragon, Erato appears alone, as a female sirvente. The Muse is depicted holding a musical instrument, and with the attributes of myrtle and a swan assigned to her by the humanist tradition for her role as the protectress of marriage. In the closing image of the Panel (Fig. 13), breaking down the abstract spatial barriers between the illuminated page and the real world of a marriage ceremony, the Muses appear in a rural context, involved in the contest resulting from the challenge made by the Pierides.

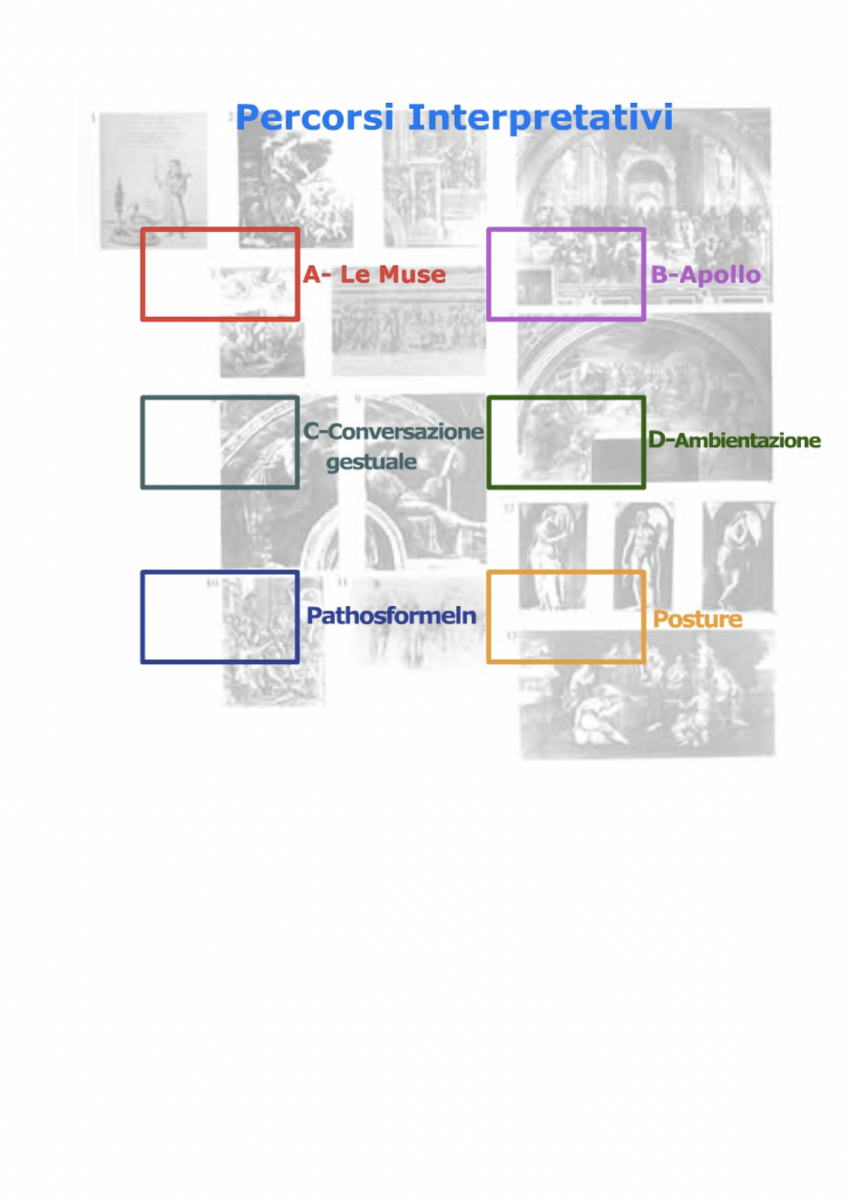

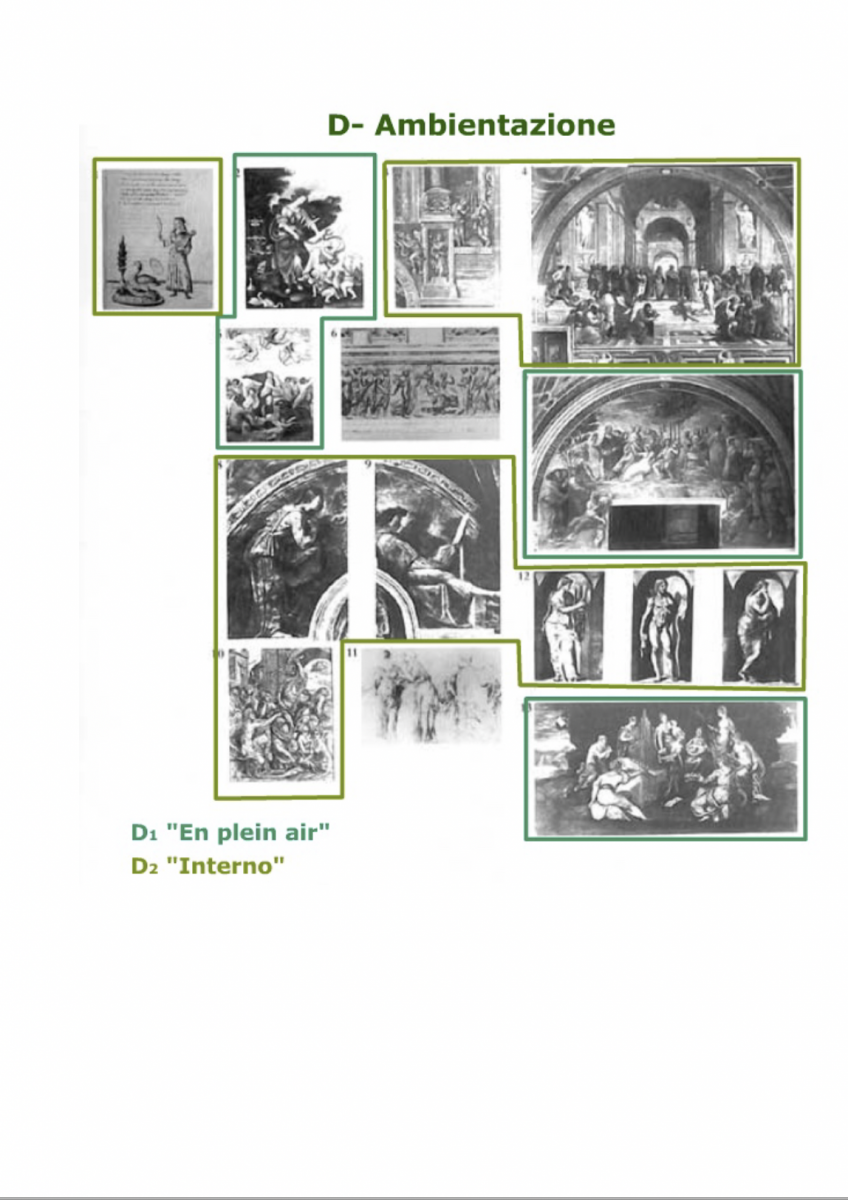

It is possible, therefore, to pursue two interwoven threads throughout this Panel — chronological eras and settings for the Muses, the protagonists, direct or otherwise, of the whole panel, as they alternate between internal scenes and en plein air.

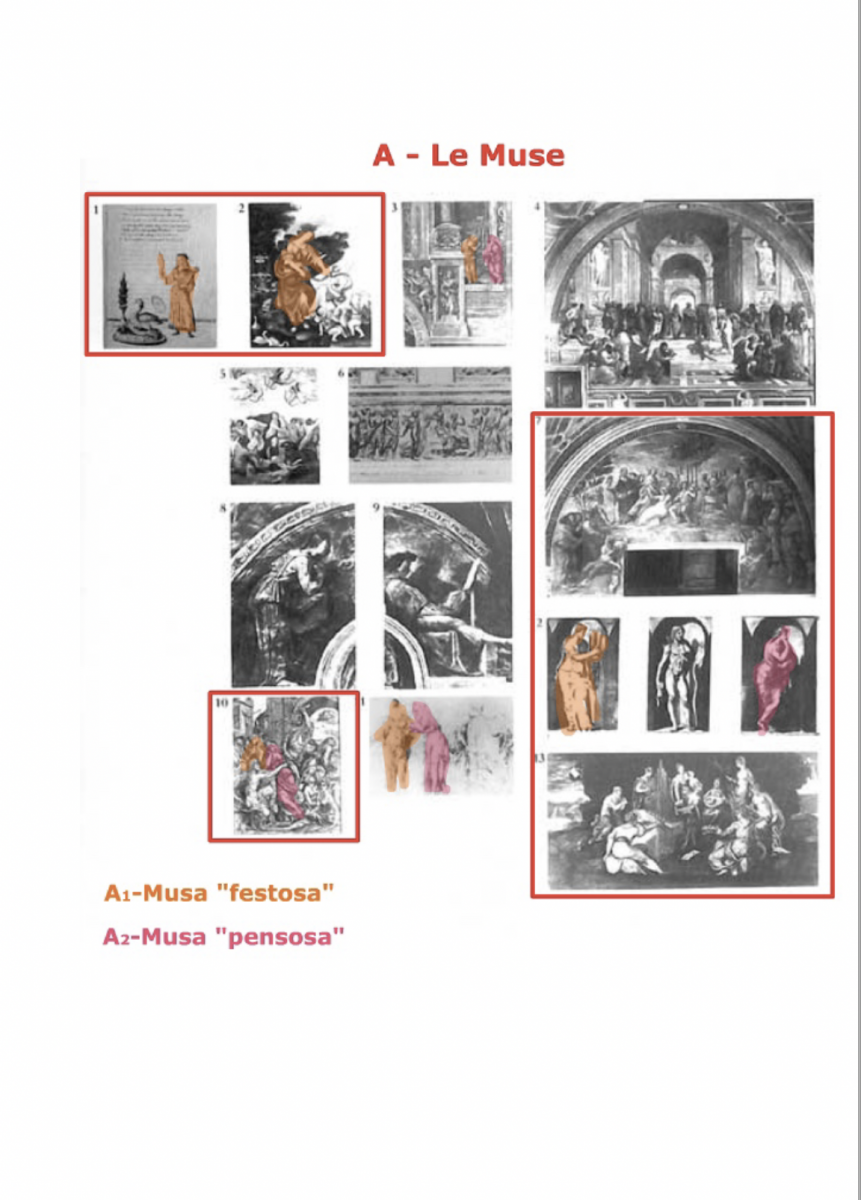

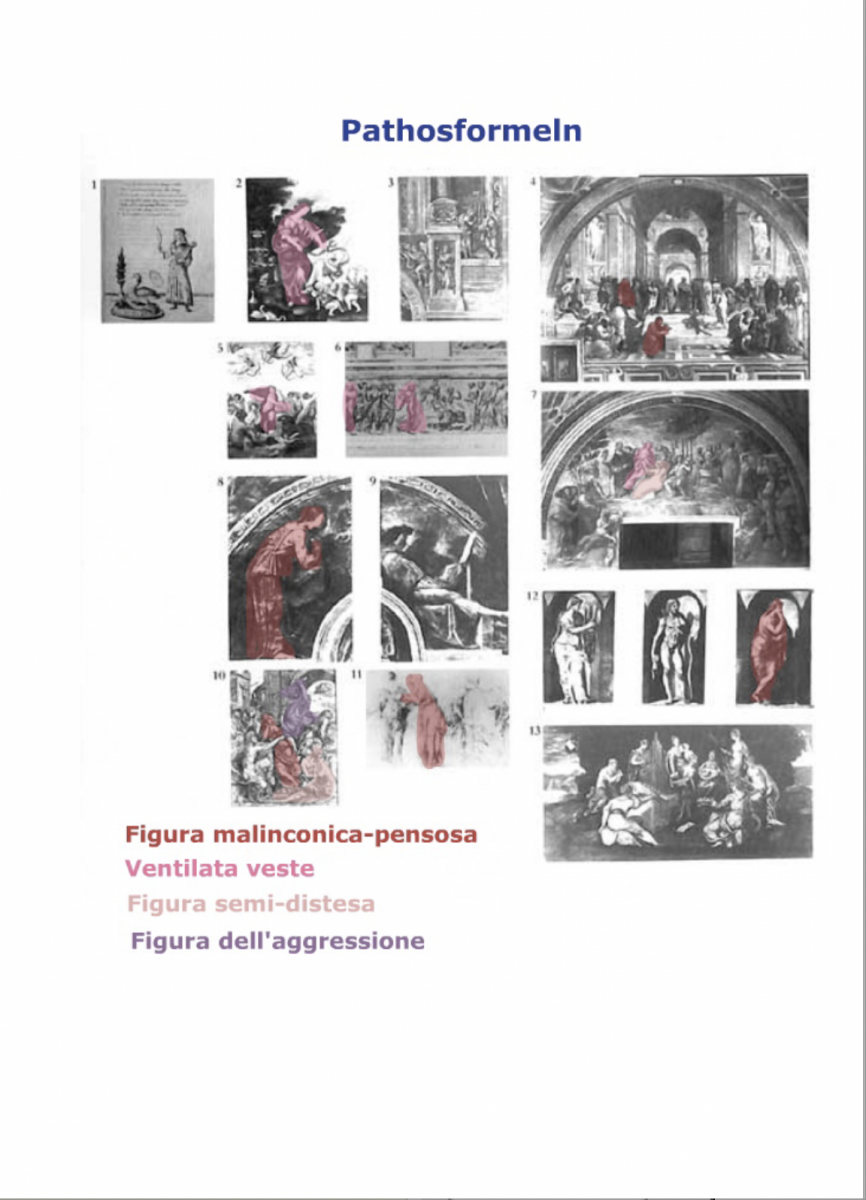

Beside and underneath the Erato of Fig. 1, an attractive Muse in the guise of a lady-in-waiting, one can see the female figures painted by Filippino Lippi (Fig. 2, Erato) and Rafaello (Fig. 5, Galatea, 1513), their garments swollen by the wind. Linked by a series of interrelated oppositions (Fig. 1 is a mirror image of Fig. 2; Fig. 2 is a mirror image of Fig. 5), the worldly composure of the Erato in Fig. 1, dissolves into sinuous movement in the Muse depicted by Lippi, who turns her head graciously towards the swan and the cupids at her feet.

This movement then explodes into the twisting motion of the Galatea of the Farnesina, whose only covering is wind-blown drapery that flutters above her head, as she looks behind her, replicating the movement of the draping cloak over the garment that covers the modest figure depicted by Lippi.

The progressive dynamic development of the female figures involves and attracts the images of Figs. 3 and 6, and defines a compact group (1-6) at the heart of the Panel. In the bronze relief of Lorenzetto depicting Jesus and the Samaritan dated 1520 circa [Fig. 6], as well as in the figure on the left that replicates in almost exactly the same way the twisting motion of the Galatea (or the other way around), one can see the powerful expression the nympha gradiva, a female figure with emphatic body movements.

This Maenad, a pagan figure par excellence, and a fugitive from an ancient sarcophagus, has been ensnared in this image and has been thwarted into the role of Samaritan. Over the bas-relief from the Chigi Chapel, among the fictive relief figures from the Strozzi Chapel painted by Filippino Lippi, we can once again see supple, twisting bodies and draping garments fluttering in the wind.

The introduction of this work, however, opens up other suggestions for interpreting the Panel. Figs. 3 and 6, in fact, are the only images in the entire Panel that portray Christian themes. The classicising figures, directly extrapolated from the repertory of pagan themes and iconography, have been naturalised by a process of unstrained interpretatio christiana in scenes that are purely religious.

This process of naturalisation manifestly involves the figure of the Maenad-Samaritan of Fig. 6, but it also involves the two figures facing each other in conversation in Fig. 3, a model and cipher of a further play on tension, both formal and semantic. Indeed, the group of figures at the top right, next to the central figure of Fides framed within the plinth of the column, includes a female figure with her head turned towards the left, her dress flowing, and her left leg slightly bent — exactly like the Erato in Fig. 2 — and another, also in classicising garments, with her face resting against her hand and her torso bent forward.

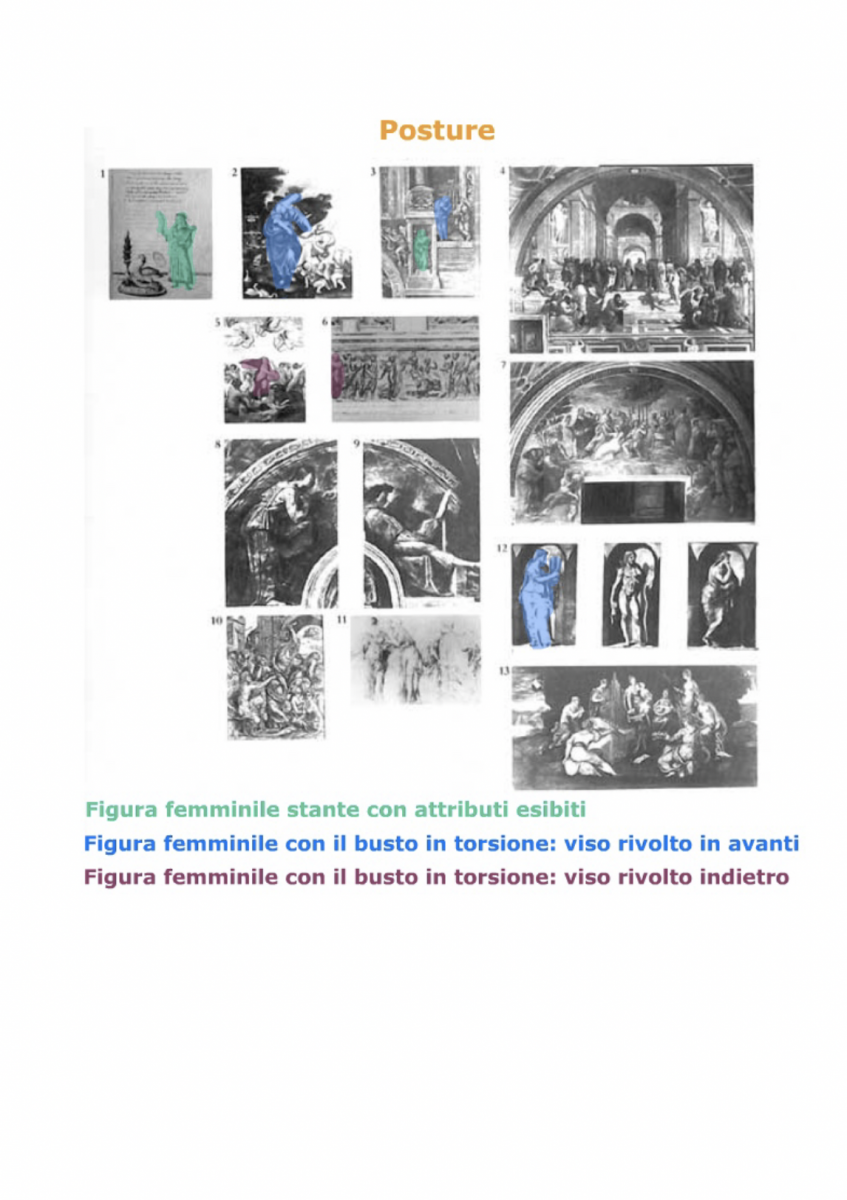

The postures of these two women in dialogue can also be seen in Peruzzi’s copy of Ugo da Carpi’s work depicting Hercules driving envy from the Temple of the Muses (Fig. 10, early C16th); in Bandinelli’s ink drawing (Fig. 11, 1530); and in Raimondi’s copy of Rafaello’s Apollo and the Muses.

The traces scattered between the images in the Panel lead to a reading of the two classicising figures of Fig. 3 as variants of the image of the two Muses in conversation. Furthermore, the scheme that we could define in terms of ‘Gracious Muse/thoughtful Muse’ is a distant recollection of Figures 1, 2, 5, that are referable to the first typology, and 8 and 9 (Naason and his wife, Michelangelo) that belong to the second.

The posture of the Muses, and indeed the entire series of the nine Muses, each with her own attributes and definite character, derives, whether directly or indirectly, from sarcophagi of late antiquity.

The canonical example proves to be the sarcophagus at the Louvre dated 200 AD in which all nine Muses appear with their conventional attributes and postures. In this important figurative text one can discern the search for a compositional intention that on either side of the central figure of Pollinnia in thoughtful pose aligns from the left figures of Muses who are composed, (Clio and Calliope); figures of Muses who are joyful (Thalia, Terpsichore — Euterpe, Erato), and figures of Muses immersed in thought (Urania and Melpomene). However, during the course of their long tradition and their changing fortunes as they have passed from fame into oblivion and back again their characteristics far from remaining fixed, have been subject to semantic and iconographic variations and fluctuation.

During the era of the Hellenistic-Alexandrine tradition, the daughters of Mnemosyne were made redundant as a result of the decline of all the categories of poetry with which they were associated, and were soon replaced, and later set alongside, the up-and-coming seven Arts.

Even the number of the Muses underwent variations, from the one Muse originally invoked by Homer to the variable numbers of the Moousai of the classical tradition whose numbers vary between three, seven and nine, until finally fixed during the Hellenistic-Alexandrine tradition to nine. After a period of obscurity they make a reappearance in the Malatesta Temple (Rimini) in a group of nine alongside the seven liberal arts, where they are also joined by a tenth Muse, the eighth Art, Architecture (cfr. Panel 25 of the Atlas with the images of the decorative cycle in the Malatesta Temple).

In his montage of Panel 53, therefore, Warburg highlights the polarization between the character and posture of a gracious-joyful Muse (1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13) and a thoughtful Muse (3, 8, 10, 11, 12). In Figs. 10, 11, 12, both typologies appear, whilst in Fig. 3 a real dialogue is established and the two figures are taken as unique models for two versions of the Muse and the twin aspects of her character, joyful and contemplative.

In the allegorical tradition of the late Renaissance, the Muses once again retire from the scene making way for the old and new arts. However, they endure in a kind of iconographical contraction that reduced the whole group from nine to two as allegorical figures of wisdom in the form of a model couple that gives expression to the double face of poetry — melancholic and joyous. At the centre, as in figure 12, is Harmony, discord brought into agreement by Apollo.

Towards the middle of the C15th lack of relevance, a feature of post-Renaissance mythography, gradually lead the Muses away from their significance and they finally become a generic group of maidens playing musical instruments, according to the musicologist Giovanni Morelli and his theory of “emoraggia della pertinenza”: so they appear in the work by Tintoretto that forms the closing image of the Panel.

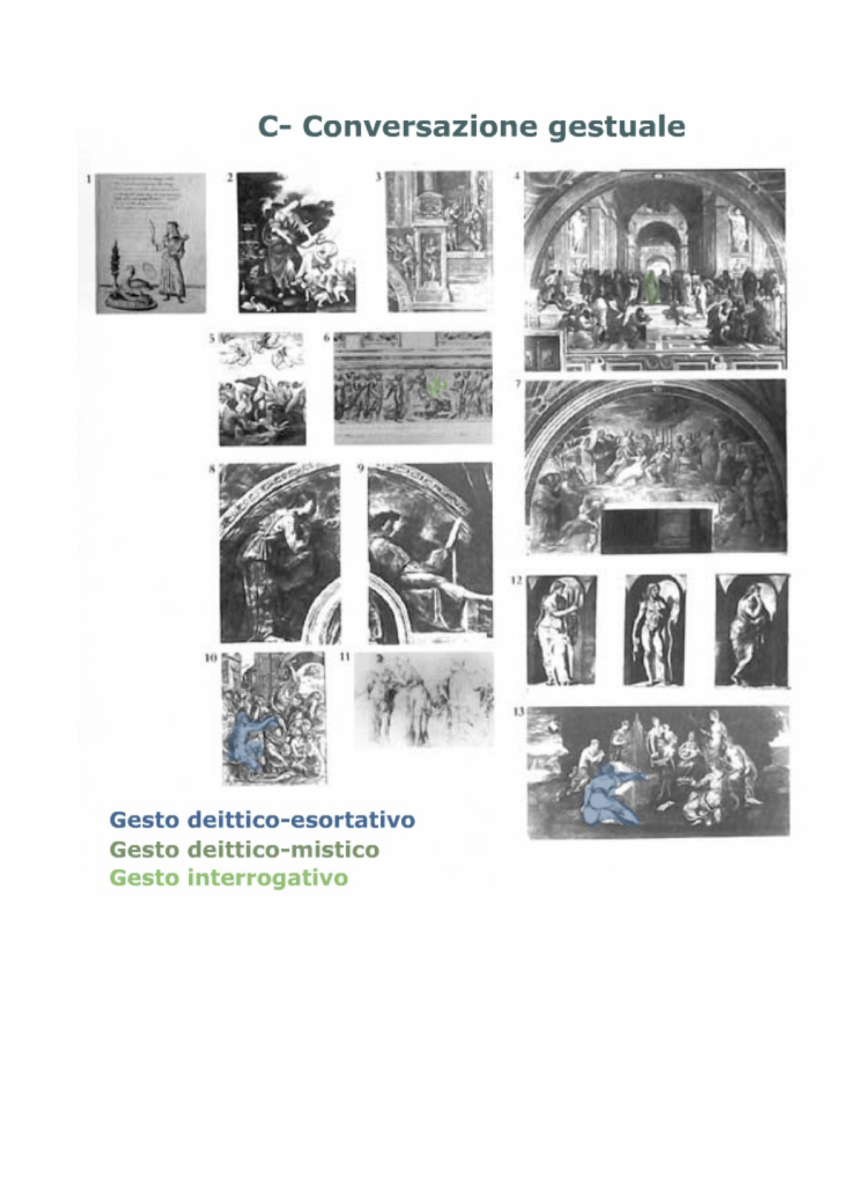

The opposition between gracious Muse and thoughtful Muse in Fig. 3 offers a further itinerary for interpreting the Panel: the image of a dialogue that is no longer typological, but that consists of an exchange of gazes and eloquent gestures. At this point, all the works that have been reproduced and pinned to the panel can be analysed.

A dialogue is taking place between the cherubs and Erato whose face is turned towards them and towards the swan tied with a ribbon (Fig. 2); the same is true of Galatea and the Cupids whose arrows are ready to be fired, and also for the figures in the retinue who embrace and exchange glances (Fig. 5).

Much more manifestly, a conversation, linked between specific groups of people is being conducted between Christ and the figures standing in front of him (Fig. 6); between the philosophers in the School of Athens (Fig. 4) — in the gestural dialogue between Plato and Aristotle at the centre of the painting — and between the divinities on Mount Parnassus (Fig. 7). The eloquent gestures that are interwoven with the conversations are repeated with more or less semantic meaning, within the various scenes on display, as they carry out the functions of compositional ‘hooks’ linking various figures, or as ‘intersections’ where variations of meaning affect all the works.

Plato’s almost mystical deictic gesture in Raffaello’s work, and Apollo’s eloquent and effective gesture, aimed at banishing Envy and inciting Hercules to attack in the engraving by Peruzzi, should be seen in this perspective. The gesture is repeated, and is almost identical in both cases, but the semantic and compositional value is quite different from the figure seen from the rear seated in the forefront to the left in Tintoretto’s work (Fig. 13).

Having followed the concentric circles, or rather the spiral that, from the first impressions garnered from looking at the opening and closing images of the Panel, branched off and drew in and linked all the images of Panel 53, the two points of departure, Figs. 1 and 13, no longer appear to be the extreme points of a chronological itinerary or two opposite poles in modes of representation.

Rather, they are two examples of the beauty of antiquity that at the beginning and end of the Renaissance are restored as models of an acknowledged auctoritas, but that from a semantic point of view have little in the way of distinguishing characteristics. Indeed, in the works that open and close the Panel, myth, albeit from a formal and chronological distance, is nonetheless used as a repertory for the occasion they are brought in to serve. In Fig. 1 Erato is the image used for the celebration of a marriage; in Fig. 13 the Muses and the Pierides, in roles that could be allegorical or real, are the pretext for a genre scene portraying a concert in the open air.

Following the traditional sequence for reading the Panel, it is possible to trace a circle, not a thread, between the beginning and end of the Panel that brings together two different consequences of the attitudes towards the generic use of antiquity. Within this circle a comparison and contest with the classical model that engaged the artists of the Renaissance, albeit with a completely different semantic tension, takes place, and in Panel 53 are represented in the celebrated examples of Raffaello and Michelangelo.

Panel 53, taken as an example of one of the mechanisms that makes the entire Atlas function, shows how the preceding Panels, but chiefly the ones that follow, are crucial to the discourse of interpreting the montage and the layout not only of the images in each panel but also of all the panels within the Mnemosyne Atlas.

If initially it appears difficult to find a connecting link between the Muses of Panel 53 and the knights of the preceding panel (52), their relationship with the images of Mantegna’s Tarot cards shown in Panels 51 and 52 is obvious. A comparison between a drawing of the Roman sarcophagus portraying Pan, Dionysus and a Bacchante, and the Muse Erato in the Tarot cards (50/51.7.8) needs no clarification. It is an association that immediately evokes not so much the shapely Muse who also inhabits Panel 53 as the Maenad-Samaritan in Fig. 6.

By presenting the other face of the Muse, the thoughtful one, personified as Poetry (50/51.4), panel 50/51 is also linked with all the melancholic figures, with their hands to their faces shown in Panel 53. It also further broadens considerations on the re-use of classical figures of myth with the inclusion of the inventions of a champion of the early Renaissance, Andrea Mantegna, Parnassus (50/51/22), Minerva driving vices away (50/51.23), works that can be compared with those of Michelangelo and Raffaello.

If one moves on to the following panels, the apparently secondary half-prostrate figure of Panel 53 acquires the role of a guiding image in an itinerary that from Panel 4 (4.1.6) to Panel 58 and beyond, presents the Pathosformel of the ‘river god in mourning (depressed)’ as the antithesis of the ‘ecstatic (maniacal) nymph’.

Panel 54, which could be labelled ‘the Chigi Panel’, is populated by images of works that maintain the theme of Christianised paganism during the Renaissance in the cupola of Santa Maria del Popolo (54.2), but made worldly via the works of Raffaello and Peruzzi in the free figures painted in the Galatea Loggia (54.3).

From among the figures pinned to Panel 54 emerges a figure shown in Fig. 3, and then enlarged and magnified in Fig. 5 (54.5). It turns out to be Eridanus, the river god who together with the semi-prostrate nymph is engaged in contemplating the rural scene, and the beauty of nature — a theme suggested once again in Panel 55, connecting antiquity, the Renaissance and modernity in the work of Manet (55.17.18).

Panel 56, (that among the many works of Michelangelo also displays Naason and his wife, Figs. 53.8 e 53.9), also shows three drawings by Michelangelo depicting Eridanus as he receives within his arms the unfortunate Phaeton who has fallen from the sky after the disastrous flight in his father’s chariot.

Neither masculine nor feminine — as already heralded in Panel 4 and confirmed throughout the entire Atlas and then made absolutely clear in the panel dedicated to Dürer, Panel 58, (58.5.3) — the emotional ecstatic-depressed polarity of the semi-prostrate figure and its derivatives are at one and the same time the sign and the origin of the melancholic intellectual who poses with his head resting in his hand (58.9); of the nymph gazing out of the picture to interrogate the observer (55.14); of the thoughtful Muse (53.12); and of both Mary’s and John giving way to their grief in Panel 42 (42.5).

English abstract

This Mnemosyne Atlas’ essay aims to present the evolution of the Muses, that are Mnemosyne’s daughters. These figures, usually found by sarcophagi, were important examples for the renaissance’s authors of twisting bodies and floating garments. The Muses were later reinterpreted in a christian key, as the Maenad-Samaritan figure shows, and the dialogue between pagan culture and Christianity developed, in association with the new importance of gestures and geometric forms, so they no longer were two opposites poles.The Homer’s myths became now a source of inspiration, allowing the development of the Muses themselves, that during centuries weren’t stuck to the single Calliope mentioned by the author, but they transformed into the nine Moousai that we know and that are analyzed in this essay in their artistic path.

keywords | Muses; paganism; sarcophagi.

keywords | Warburg; Mnemosyne Atlas’ Panel 53.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Seminario Mnemosyne, Mnemosyne Atlas’ Panel 53. The Muses, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 13, dicembre 2001/gennaio 2002, pp. 33-39 | PDF