De melancholia

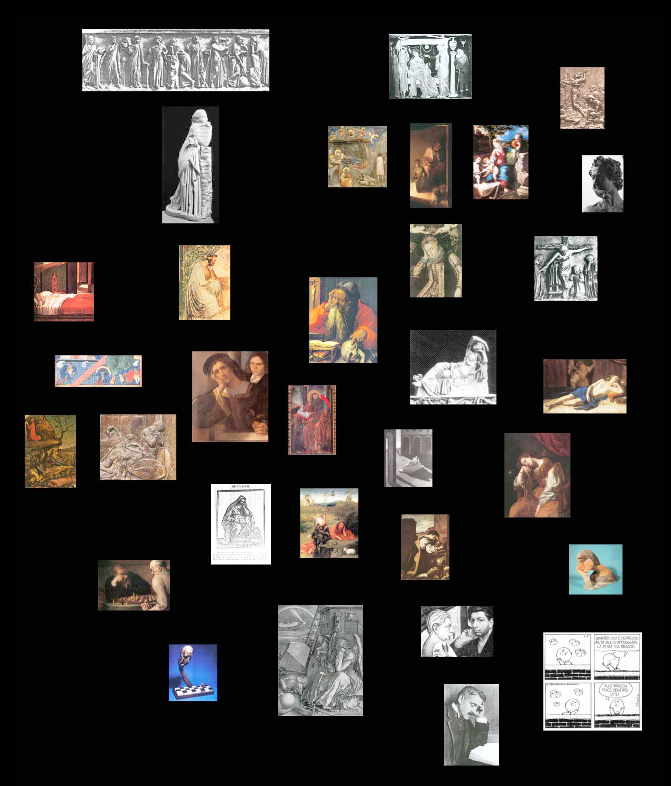

A new Panel, after Mnemosyne Atlas’ Panel 53

edited by Seminario Mnemosyne, coordinated by Monica Centanni. Translated by Elizabeth Thomson

English abstract | Versione italiana

Panel ex novo De melancholia

This new plate is the result of expanding on Warburg’s ideas that arose from our interpretation of plate 53 of the Atlas based on the Muses (see: Engramma no. 13), and from the thematic plate on the figures of melancholia throughout the Atlas (see: Engramma no.14).

The images collated in this plate have in common a postural convention that suggests a formula of pathos that does not have a unique, singular meaning. They are figures of melancholia, but what kind of melancholia? The figures assembled in the plate share a posture that is symptomatic of a want of temperance — specifically excessive black humour — that nonetheless manages to remain on the positive side of the threshold of a pathological condition, and manifests itself as a personality trait, in the form of ‘humour’.

The various stages and the different declensions of melancholic humour draw a complex map that, as has already been said, does not result in the ailing state of depression, but rather, to some extent heralds it in the various stages of the manifestations of its symptoms.

According to Ludwig Binswanger and his theory of Daseinpsychologie, the investigation of psychic phenomena assumes the attempt to understand the constituent structural forces that regulate the human being during a certain existence in this world, in order to understand his deficiencies, defects, and the unsuccessful functioning of Dasein — of ‘existence in this world’.

His examination is based on the pure transcendental Phenomenology of Edmund Husserl, cross-fertilized with Martin Heidegger’s a priori concept of ‘being’, of existence in the world, as the theoretical approach for elaborating a psychological theory and a psychiatric methodology.

The constituent structural forces are the a priori transcendental forces that are like the matrices of different worlds. These constituent forces of Dasein are essentially the intentionality connected to temporality, to the subjective temporal conscience and therefore to protentio (whose temporal object is the future), retentio (the past), and praesentatio (the present). Psychosis confirms a defect in these dimensions which all occur simultaneously. Within this framework, melancholia is defined also by its opposition to the other manifestation of a defect in temporal perception: mania. Binswanger says that each has a different defect in its temporal composition. In the case of mania, it is a slowing down of the temporal composition of the ego that is revealed by the complete withdrawal of the retentive and protentive transcendental forces and of the habitual apprehension of pure actuality, as well as a defect in the apprehension of the composition of the alter ego and therefore of the ordinary world. In the case of melancholia it reveals itself in the loosening of the plot of the intentional composition of temporal objectivity, and manifests itself in the intermingling of retentive with protentive forces (melancholic self-accusation), or of protentive with retentive forces (melancholic delirium).

Following the theoretical trail maintained by Binswanger, the melancholic personality manifests itself in a distorted relationship between ‘being in the world’ and time, and in an unbalanced and unsatisfctory relationship with praesentatio (existence in the present) that inclines towards the protentio (whose temporal objective is the future), or retentio (whose temporal objective is the past).

Melancholia, therefore, is seen as a painful (albeit not pathological) alteration of the perception and composition of a temporal horizon. It is also a gradual decline in a continuum that can be described as characteriological depression: the humoural constant of melancholics can (or not) have episodes of greater depression, but during the intervals, they maintain a tendency — variously inclined and expressed — towards pessimism, unhappiness and the absence of the pursuit of pleasure. The persistence of this personality disorder in melancholics is a further factor that distinguishes the humoural condition from the pathological — manic depression for example — which manifests itself in a marked bipolarity that oscillates dramatically between depression and mania.

The figures that are assembled in the composition of this plate can be split into three groups which, in order to formulate a scheme that will articulate our argument, we have categorised as: 1) melancholia ex otio; 2) melancholia ex acedia; 3) melancholia ex maerore.

Melancholia ex otio

Otium is the time freed of material concerns and the anxieties associated with them and is an empty space filled with thought. Otium is the moving force of meditation and poetry.

The first figure of otium is the Muse whose meditative pose passes, as though by contagion, to the inspired poet: chief among them Polyhymnia, the muse of hymns to the gods, a figure of absorption, of the introspective concentration "that to poetry leads". From this typology descends the melancholia resulting from the meditative and inspired concentration of the Holy Wise Man (see Saint Gerome), who by relocating from his hermit’s cave in the desert to his study, becomes the archetypal figure of the Humanist. Melancholia — a saturnine trait — from excess of the humanist’s wisdom (see the works of Dürer and Giorgione) leads to the portrayal of the intellectual (see the self-portraits of De Chirico, Duchamp, Martini, and the photograph of Warburg) until it becomes the conventionalised and eloquent posture of the thinker (see the Charlie Brown cartoon strip). This declension of the melancholic trait can be sublimated in what Gertrud Bing, in terms of Aby Warburg, describes as the “holy dissatisfaction” of the scholar who transfigures his anxiety, his ‘original flaw’, into the endless search for new ways to wisdom.

The poietic restlessness of the genius and artist (in Binswanger’s terms, a form of protentive melancholic delirium, projected beyond the dimension of what is actual into figurations of new matrices of the world) can nonetheless be a fertile moving force. These forms of melancholic restlessness also herald pathological derivations in several symptoms that are recognised as characteristic of serious depression — abnormal indecisiveness, recurring thoughts of death, suicidal thoughts. In the psychology of the intellectual and artist, the result can be a self-referential creative empasse, a compulsion towards suicide, either symbolic (Nietzsche) or real (Van Gogh). Meditative otium, signalled by the conventional posture of the melancholic, can also give rise to figures of enlightenment: ecstasy, prophecy ex somnio (Saint Ursula, the soldiers near the Sepulchre of the Risen Christ), and projections of ‘protentive delirium’ with visions of the future.

Melancholia ex acedia

Melancholia ex acedia declines in a completely different way. The want of interest and concern for the present, often projected in a ‘retentive delirium’ of regret, nostalgia and remorse, provokes not a burst of poiesis, but a regression into an empty abyss. The symptoms of the pathological repercussions are apathy, isolation, fatigue or lack of energy, lack of self-worth or self-esteem, and feelings of guilt. This tendency of melancholia, failing to find release or a form of statement (as in poiesis ex otio), settles into absolute self-referentiality that leads to embitterment through endogenous black humour. Paradoxically, unlike the intellectual, black humour has pathological symptoms that reduce the capacity for thought and concentration, and in extreme cases lead to physical and mental paralysis. A typically expressive figure of this emotive formula is the melancholic Joseph who, not without his doubts, banishes himself to the confines of the nativity scene, his sullen statement and his solitary figure darkly counterpointing the real and symbolic light that surrounds the birth of Christ, his emotions giving way to resentment.

Melancholia ex maerore

The third declension of melancholic humour can be defined by melancholia ex maerore: it is mainly in this typology that one is confronted by the problem of the dividing line between the ‘normal’ state — otherwise known as ‘characteriological’ — and the pathological state.

Melancholia ex maerore is unleashed by external phenomena — grief and mourning for example — that are experienced in a way that is consonant with the humoural condition of the melancholic who reacts by containing his grief rather than expressing it emotionally. In this case the gesture of the hand to the face can indicate the desperation and anxiety that has no outlet through tears or agitated gestures as well as introspective withdrawal into grief and reflections on death. This occurs in the recurring posture of St. John in scenes of the lamentation over the body of Christ (see the mosaic in St. Mark’s Venice, the relief in the Carmini Church in Venice, and Niccolò dall’Arca’s work): the formula of pathos carries a profound but repressed message of grief and loss. The posture, from the ‘theatre of mourning’ (derived from sarcophagi of Alcestis and Meleager portraying contained and melancholic figures, up to and including scenes of the lamentation over the body of Christ [cfr plates 5 and 42] ) assumes a powerful valence in the syntactic polarity between an attitude of mania and an attitude of depression in the face of mourning. In the dialectics of composition that bring together agitated figures screaming with grief and figures of contained desperation whose grief is silently contained, the formula of pathos of the hand to the face has a valence which is the opposite of uncontainable expressions of emotion.

The instability and the fertile perviousness between these typifications is manifest at the point where the three tendencies meet — thought, passivity and grief — which are present in almost all the figures of melancholia, but mainly in some figures that are ‘liminal’ in relation to the predefined categories. The montage of the plate, via complex relationships and connections, offers further articulations of the tripartite scheme by overlaying its components.

Abandonment

The figure of Ariadne, typified by the formula of pathos of hand to face signifying melancholia is an example of this, as is the posture of the arm bent behind her neck felicitously defined as ‘a double abandonment’ (Mosè Viero), in a posture that can be defined as languid, erotic-ecstatic-contemplative (ex otio), but also in the sense of repeated abandonment by Theseus and Perseus (ex maerore). It is a complex formula of pathos that can be found in ancient iconography as a sort of iconographic contraction of the entire myth of Ariadne, who in due course would be rehabilitated in the fullest sense in De Chirico’s Ariadne. Another example of this kind of contamination on the boundaries of melancholia is the mournful image of Elizabeth I whose feelings of weekness restrict her to a state of enforced impotence (melancholia ex acedia), but also drive her to intellectual preoccupation with the vanity of power and the sterility of existence (melancholia ex otio).

Dream/vision/premonition

Although there is research to be done in this area, as one compares and contrasts the postures, one becomes aware of an obvious postural and compositional convention and the semanticisation of one or more figures, whether intentional or not. This awareness is suggested — unintentionally — by plate 30 of the Mnemosyne Atlas in the figure of Constantine’s guard (cf. Figures of grief and melancholia in the Atlas of the Memory) by the recurrence of figures immersed in thought, with hands to the face, in contexts of miracles. The places where these events occur and the roles of the figures featuring in them vary, but they share the world of sleep and dreams whether by day or by night and not always with their eyes shut. It is through the miraculously healed or through visionaries that Grace is revealed, as is the case with Carpaccio’s portrayal of Saint Ursula visited in her sleep by the ray of divine light. Miraculous events occur in the presence of the heedless, the guilty, and those who are unaware of what is about to happen — at the moment of Christ’s most intimate crisis, the Apostles are abandoned to sleep (again, see Carpaccio, Prayers in the garden), and are depicted in conventional yet eloquent postures, as are the soldiers guarding the Sepulchre, irrespectfully immersed in a deep sleep, yet seemingly affected, almost humbled, by the miracle of the Resurrection in Luca della Robbia’s illumination.

Lament

The gesture of the hand to the face also characterises figures of grief in the ‘theatre of mourning’. In portrayals of funerals dating back to ancient times, weeping mourners, veiled or otherwise, present at the seen of the death of Alcestis, are depicted in this posture (see Greek vase), a formula of pathos that is not restricted to the female figure.

In the vase painting, the figure of the old pedagogue is significant — standing aloof from the others and bent over his cane, he is still a participant in the events. He is a recurring figure in scenes of grief and mourning and can be seen powerlessly holding his hand to his face, prefiguring the posture that in a Christian context would typify Joseph in scenes of the Nativity.

From ancient portrayals of mourning, the gesture becomes a characteristic of withdrawal into grief in the face of death in representations of the Passion of Christ, and typifies St. John (see Saint Mark’s, 13th century relief, Squarcione, Francesco di Giorgio, Niccolò dell’Arca), whose melancholic demeanour — expressing degrees of emotion that are more or less intense — is offset by the expressive fury of the Maries.

Speculation

The same postural feature, but with a reduced emphasis on the pathos, characterises the meditative and listless demeanour of the elderly Joseph in scenes of the Nativity (figs. mosaic, Beccafumi, Giulio Romano), in which the saint’s secondary role is confirmed by his place in the composition (figs. Beccafumi, Giulio Romano). During the Renaissance even Saint Anne, absorbed in her thoughts as she gazes at St. John or Christ, is depicted with her hand to her face (figs. Giulio Romano, A. Gentileschi). The posture, therefore, would seem to be typical of melancholia ex acedia, a typically saturnine trait, due to old age.

Apart from the bewilderment and speculation kindled by miraculous events like the Birth of Christ, the formula of pathos is also indicative of a philosophical and meditative disposition preoccupied with the transitory nature of existence and its worldly concerns. Exemplars of this emotive state are the figures of Saint Jerome and Saint John, both depicted as elderly men (see the works of Dürer and Bosch). Dürer in particular uses just such a precedent of a Portrait of a ninety three year-old man for his depiction of Saint Jerome. Throughout the ages, this posture remains characteristic of the same abstract meditative attitude, and also semanticises the depiction of Mary Magdalene, penitent, that ends up as a figuration of true and proper vanitas (see Magdalene, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Melancholia, Fetti): Both Jerome and the emotional Mary Magdalene are depicted with the attribute of a skull. Despite the time lag Arturo Martini’s sculpture, The Whore, a re-emergence of an engram of a formula of pathos, is comparable with the depiction of Mary Magdalene.

The allegorical portrait of Elizabeth I, whose name would be forever associated with the art production of her era rather than with the descendants she failed to have, portrays the fusion of meditation on death and purely intellectual reflection.

Secular philosophy

In the example of Elizabeth I, we can see one of the genes that links the figures of philosophical thinkers who are freed of the mortal sin of sloth of the middle ages, and who have become instead proud representatives of intellectual emancipation no longer bound by mystical and religious thought.

At opposite extremes — for both their artistic quality and semantic complexity — these figures are exemplified in Durer’s most famous engraving, and also in Ripa’s ‘visual summary’ of the same, la Meditazione. Geographically and chronologically displaced, these images of intellectuals are all characterised by their own imprint, the gesture of the face, leaning against, or supported by, the hand, as the person depicted reads, writes or simply thinks.

The Giottesque portrait of Dante in Ravenna is represented in this way as is the gentleman of the portrait attributed to Giorgione who shows the object that symbolizes and bears the name of the ailment that afflicts him, a ‘melangolo’ or bitter orange. De Chirico’s self-portrait with his declaration of plagiarism also falls in this category of images. For its semantic dissimilarity, and obvious formal similarity, the posture also characterises the two players (Daumier, Duchamp) in a reference — by contrast — to Vanity (the game of Chess with Death). This postural convention is sometimes semanticised merely via the eye of the beholder: the face leaning against the hand becomes a photographic ‘equation’ (see the portrait of Warburg = thinker).

This also applies to Charlie Brown, Schultz’s invention, who supplies us with a clear explanation for his posture and frequently seeks consolation in the ‘psychiatric help’ offered at 5 cents by Lucy van Pelt.

English abstract

The images collated in Plate 53 have in common a postural convention that have different meanings. The figures share a posture that is symptomatic of a want of temperance that links to a pathological condition and manifests itself as a personality trait. There are various stages of manifestations of its symptoms. The constituent structural forces are the a priori transcendental forces that are like the matrices of different worlds. These are the intentionality connected to temporality, and therefore to the present, the past and the future. Psychosis confirms a defect in these dimensions which all occur simultaneously. Melancholia is so defined also by its opposition to other manifestation of a defect in temporal perception. There are different defects: there could be a slowing down of the temporal composition of the ego and of the habitual apprehension of pure actuality or in the apprehension of the alter ego and of the ordinary world. There could be also the loosening of the plot of the intentional composition of temporal objectivity and it manifests itself by melancholic self-accusation or melancholic delirium. Melancholia is therefore seen as a painful alteration of the perception and composition of a temporal horizon. It is also a gradual decline as a characterological depression.

keywords | Warburg; Mnemosyne Atlas’ Panel 53; Pathosformel; melancholia.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Seminario Mnemosyne, De melancholia. A new Panel, after Mnemosyne Atlas’ Panel 53, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 15, marzo/aprile 2002, pp. 29-36 | PDF