Notes on the Warburg Library (1934)

Gertrud Bing

Gertrud Bing, The Warburg Institute, “The Library Association Record” Fourth Series, IV, 8 (1934), 262-266, ripubblicato in G. Bing Notes on the Warburg Library (1934), edited by Seminario Mnemosyne, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 177, novembre 2020, 15-23.

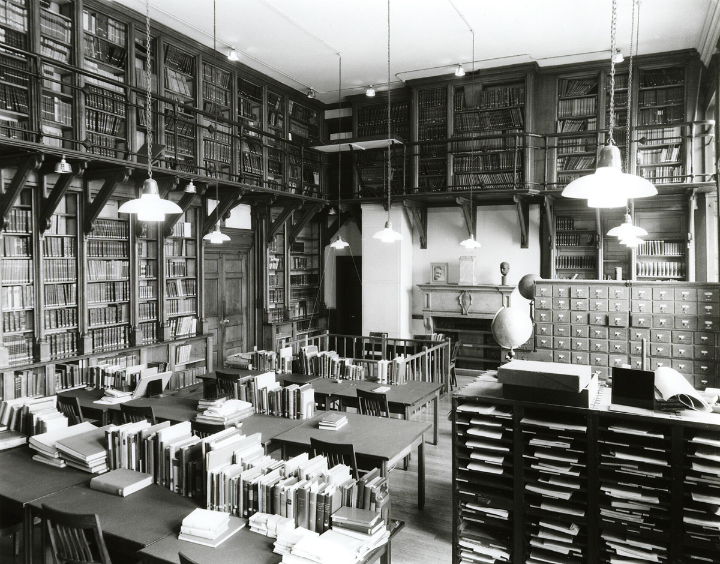

1 | Sala di lettura del Warburg Institute presso l’Imperial Institute di South Kensington tra il 1936 e il 1957.

In an earlier article in the RECORD (Vol. III, 1933. No. 8, p. 247) mention has been made of a happy distinction between two types of libraries: the ‘laboratory’ type and the ‘museum’ type. The Warburg Institute may be described as belonging to both. It is a laboratory in so far as it devotes itself to a specialized field of research, the interest in and the method of which it seeks to promote; as such its purpose is one of research and education. Its scope, the tracing of Greek and Roman tradition in postclassical civilization on the other hand, is wide enough to allow its library to range over nearly the whole history of civilization, the documents of which, literary and pictorial, are displayed in the arrangement of the library and photograph collection very much in the same sense as a museum displays its treasures. It is, in fact, this double character which made the Warburg Institute develop into a new type of library; its ‘workshop’ nature determined not only the outlines of its collections but also their arrangement, their classification housing, and working organization.

It was originally a private library. A. Warburg, its founder and until 1929 its director, belonged to a generation for whom the Renaissance period was of outstanding significance on account of the apparently sudden brilliant development of a modern, independent outlook on life as opposed to the mediaeval subjection to church formulas and restrictions. Tracing the role which antiquity played in this development, he saw that Renaissance artists, scholars, and men of letters did not look for ‘classicism’ in ancient art and thought, did not seek its perfect poise, its serenity of attitude and of emotion. They felt the spell of antiquity most where the pagan temperament breaks forth in violent gestures, in dramatic rituals, enraptured dances and thiasoi. From this starting-point Warburg’s investigations developed along broader lines. He did not limit himself to the Renaissance period, but applied the same scrutiny which had yielded these first results also to other ages, asking what in the various periods, cultural centres and fields of human activity revived or transmitted antiquity signified, in what form it was received, how transformed or re-interpreted. There was shown to survive throughout the ages a sort of everlasting pagan demonism with which the Church had to struggle and sometimes to come to a compromise and which monopolized entire realms of thought and life such as those of astrology, magic, legends, and popular customs until eventually the Olympian gods of Greek and Roman mythology reemerged out of their mediaeval disguises, whether Oriental or Western, fantastic or domesticated, and humanism gave them back their Olympian character, in essence as well as in artistic form.

Another aspect to this question is the anthropological one. Asking himself under what conditions and by what means one civilization was apt to appear at a later time and under utterly different social and intellectual circumstances, Warburg recognized symbols to be the vehicles of transmission. Images such as the heathen gods and goddesses, myths and rituals of religious origin, gestures as created by art, metaphors in language, rites and customs of social life are expressive of certain fundamental psychological processes: they are symbols coined by the human mind in its attempt to understand the cosmos and man’s place in it. They belong to primitive cultures and complicated historical civilizations alike; they are transmitted through the centuries with an astonishing tenacity and, once created, possess a vitality which enables successive generations to fall back upon them whenever they want to express an attitude of mind similar to that which primarily produced them. In the case of European civilization, Greek art and mythology constituted, as it were, its maximum values of expressive force, and for good or for evil Europe turned to these time and again. The phenomenon, however, of the original evolution of symbols, and of their transmission and transformation through subsequent strata of civilization, is not limited to European conditions alone: it may be studied even better in primitive cultures because here the creative process is less encumbered by intellectual accessories.

It goes without saying that this way of treating historical facts will not permit of their being taken separately. The importance for instance of a work of art considered in its expressive value is only to be understood if its religious significance, its intellectual back-ground, and the exact social and possibly political circumstances to which it owes its creation, are taken into account. It follows, therefore, that the history of art may not be studied independently but rather in its interaction with other branches of learning which in their turn only receive their proper significance if taken as a whole.

These ideas proved to be so fertile that Warburg’s library, originally collected merely for his own studies, grew to be a centre for scholars of various descriptions; anthropologists theologians and historians of religion, mediaevalists, psychologists, folklorists, philologists and antiquaries not only found the books they needed for their special researches but found them arranged in such a manner as to suggest certain interactions with and relations to other subjects. They found, moreover, displayed in the books a conception of history as a unit, which induced them to break down the barriers between the different fields of research, to overcome the restrictions to specialized subjects which the ever increasing volume of learning had inevitably brought with it. The old idea of the “Universitas Litterarum”, last realized in the eighteenth century, had come back to life. But it had not come back as the old accumulation of detail without any distinctive values: without ever leaving the firm ground of historical facts it seemed once more possible to view history in its integrity, in relation to which each detail had its assigned place; light was shed on subjects which had hitherto received but scant attention. Two series of publications were started to make these results known and to promote interest in the Institute’s researches: one containing the lectures which scholars were invited to hold in the library; and the other series lengthy essays on subjects related to the general theme, i.e., the influence of ancient civilizations on European life and thought.

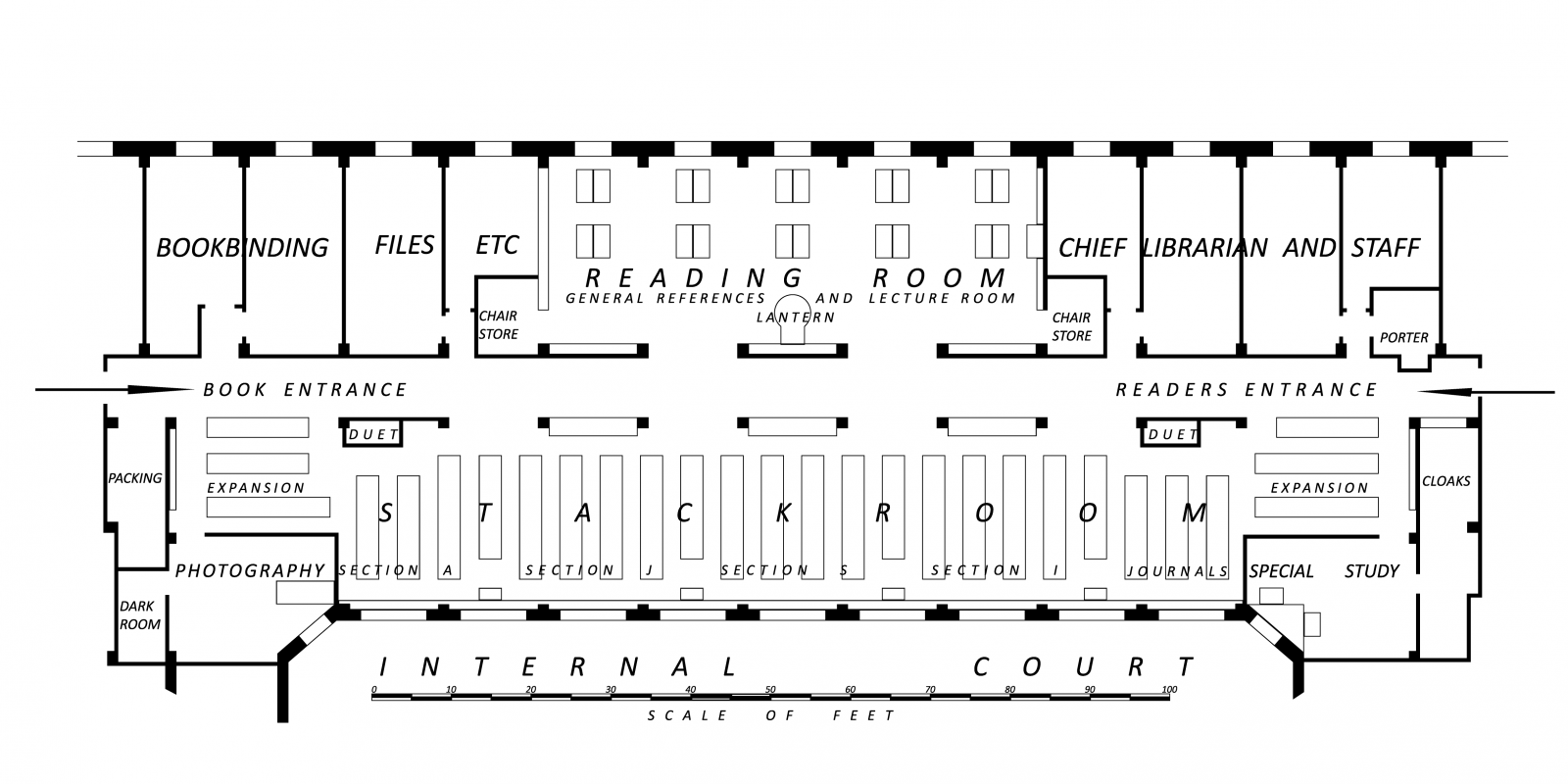

2 | Disposizione del Warburg Institute presso la Thames House a Westminster, prima sede della Warburg Library dopo il trasferimento e fino al 1936, Architetto Godfrey Samuel, membro del gruppo Tecton. Immagine a corredo del testo di Gertrud Bing.

So much for the ‘Workshop’. As regards the library, its compilation was and is directed by the subject, and by the method practiced by its collaborators and readers, The present stock of books comprises the following main sections, and numbers about 70000 volumes all in all:

First Section: RELIGION, NATURAL SCIENCE, AND PHILOSOPHY

- I. Anthropology and Comparative Religion.

- II. The Great Historical Religions, showing the development from Oriental to Classical Paganism and thence through Late Paganism to Christianity.

- III. History of Magic and Cosmology, illustrating the development from Alchemy to Chemistry, from the Lore of the Medicine-Man to the Science or Medicine, and from Astrology to Astronomy.

- IV. History of Philosophical Ideas, two special questions having been singled out: a history of Platonism leading from Plato to Neo-Platonism and its revival in Renaissance thought, and a history oi Aristotelian Philosophy, its commentaries and translations.

Second Section: LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

- I. History of Greek and Roman Literature.

- II. Survival of Classical Poets.

- III. Survival of Classical Subjects (Gods, Legends, Myths, Fables, Emblems and Proverbs, etc.).

- IV. History of Classical Scholarship – (a) Mediaeval and Renaissance Latin Literature; (b) History of Education, of Schools and Universities, of Collections of Manuscripts and Books, of Learned Travels, Encyclopaedias, etc.

- V. History of Modern National Literatures.

Third Section: FINE ARTS

- I. Literary Sources.

- II. Iconography.

- III. Primitive and Oriental Art; Pre-Hellenic Period.

- IV. Classical Archaeology, with a special section on the Art of the Roman Provinces.

- V. Early Christian and Mediaeval Art, with a special section on Illuminated Manuscripts.

- VI. Renaissance Art in Europe, with a special section on Applied Arts, Book-Printing and Book-Illustration.

- VII. History of Art Collections, Preservation of Classical Monuments.

Fourth Section: SOCIAL AND POLITICAL LIFE

- I. Methods of History and Sociology.

- II. History of Social and Political Institutions in Southern and Northern Europe (leading from the Greek City-States over the Roman Empire to the Holy Roman Empire of the Middle Ages, and thence to the City-States of the Italian Renaissance, the French, Spanish, and English Courts, etc. ).

- III. Folklore; History of Festivals (especially of the Renaissance), the Theatre, and Music.

- V. Forms of Social Administration; Legal and Political Theory.

With regard to new acquisitions, which at times amounted to 3000 volumes a year and should, it is hoped, keep up an average of 1800 to 2000, the administration is governed by two principles: the main sections (such as astrology, Italian art and literature, Florentine social history, festivals and theatre, humanism and classical scholarship. Renaissance philosophy) are kept up to date, and missing works of earlier date are supplemented. Only these most relevant sections can, in a library of limited scope and means, be kept complete. With the other sections it is a matter of buying the most important works, and of keeping them well equipped with books of reference which will supply bibliographies of their subjects to readers not versed in them. The growth and enlargement of the library, as far as it is subject to deliberate planning, depends largely on the scientific activities of its staff, its collaborators and its readers. The outlines of the library are as a whole determined, and there is no going beyond them. But within these limits it grows in the same measure as the research work gradually covers historical areas not yet represented in it. The sections on Early Christian art, and on English eighteenth century art-interpretation, developed when members of the staff worked on these themes. Indispensable books which for some reason cannot be bought are being photographed in the Institute’s studio, the negatives bound in its bindery and shelved.

Parallel to the collection of books a collection of photographs is being made without which an institute devoted to the study of the history of symbols would be incomplete. The signs, seals, and even stamps and posters may be expressive of a mental attitude or hold an intended significance. Very characteristic and especially a real depository of ancient themes most relevant of these symbols are of course works of art. That is why the history of art forms the nucleus of the activities of the Institute. But its range is extended. Furniture, heraldic decorations, tapestries, emblems and gestures are book illustrations, illuminations as well as engravings and wood-cuts. Thus the photograph collections comprises two main sections: one in which reproductions of all kinds of pictorial documents from the most elaborate works of art down to ornamented tools and implements of daily use are arranged according to the themes represented on them; and the second containing photographs of astrological and mythological illuminated manuscripts (1230 at present) extant in European and American libraries.

With regard to the classification of the library, the main consideration was that it should exemplify the ideas on which research was to be carried on. By means of an author-catalogue, a subject index, place indicators, and press-marks, the reader may easily find any special book he wants to consult, and if not interested, need not bother about the classification at all. But the classification is anything but indifferent. The manner of shelving the books is meant to impart certain suggestions to the reader who, looking on the shelves for one book, is attracted by the kindred ones next to it glances at the sections above and below, and finds himself involved in a new trend of thought which may lend additional interest to the one he was pursuing. Cardboard indicators which do not take up much space between the books, and yet are broad enough in front to take a written heading, mark the subdivisions. The books are marked with three slips of coloured paper on the back: and three corresponding letters in the press-mark. They are not press-marked individually, but rather groups of some eight or ten books on the same subject are brought together under one number, the numbers skipping and leaving space for insertions. A book on, let us say, the life of Botticelli would have at about one and a half inches from the lower edge three paper slips, one wine red, the second pink, the third dark green; the press-mark would accordingly consist of three letters: C (always standing for wine red), N (for pink), A (for dark green), and a number denoting the books treating of Botticelli’s life only. This comparatively simple press-mark is representative of the entire scheme of arrangement: colours and letters in their relative and, of course varying sequence denote a system of classification, the top colour and first letter signifying the department of study (C = Art History), the second the country (N = Italy), and the last one the respective subdivision (e.g. A = painting). Thus the second colour would reappear in the section on Italian literature, only then headed by a different top colour (e.g. light blue = E = literature). The coloured slips are to prevent a book from being misplaced books being ordered by their press-marks only. This system has two advantages: firstly it is absolutely independent of the collocation of the books on the shelves; sections may be removed, and new combinations made without fear of the press-marks no longer falling in with each other. Secondly, it comprises the entire range of the library’s present and future stock without necessitating an alteration or revision so long as the original arrangement is adhered to. It is a well-known disadvantage of nearly all systems of classification that with the progress of learning they require revision from time to time. If it has been possible to avoid this difficulty in this library it is due to the intrinsic unity of the collection, it may be refined and improved but not disproportionately enlarged. All its sections retain their comparative place and value by virtue of their being referred to one another and each related to the main thought, that of the survival of antiquity.

If the reader is to be drawn into this way of looking at things by the arrangements of the books it naturally follows that he must have free access to the shelves. The subject index, it is true, reflects the collocation of the books; as the books are placed according to subjects: subject index and press catalogue are one and the same. But the pleasure and charm of handling the books, opening them and ‘browsing’ as you pass along the aisles, can never be replaced by a card index. The educational influence of a library which invites a student to adopt a special subject and method of research can only be effective if he is allowed to be guided by the books themselves. The scholar who is expected to penetrate into the borderlands of his special subject must find the new territory ready surveyed for him by the able planning of an expert.

The library has been very fortunate in finding premises in London (3 Thames House, Millbank, SW I) that were exceptionally well adapted for it. Reading-room, stack room and staff rooms are one level. A mere passage divides the reading-room from we open stack room, so that readers may readily pass from one to the other. Tables and chairs are provided for in the stack room. A reference library reflecting all sections of the main library is available in the reading-room; in addition to which the reader will find periodicals, the last issue lying open, the current year in rollerblind cases, the earlier, bound volumes on shelves, at each end of the stack room. The reading-room is equipped with a lantern and screen and can immediately be turned into a lecture room.

The library of the Warburg Institute is a reference library; in exceptional cases books may be borrowed. It is, however, an outlier library of the National Central Library. It is open to every serious student on week-days from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m., on Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. No fees are demanded nor are there any other formalities to be fulfilled except for a written recommendation which persons not known to the administration are requested to furnish.

English abstract

In this text, written in the aftermath of the arrival of the Warburg Library in London, Assistant Director Gertrud Bing describes simply but fully the genesis, history, structure, mission, and meaning of the library conceived by Aby Warburg.

keywords | The Warburg Institute; The Warburg Library; Gertrud Bing.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: G. Bing, Notes on the Warburg Library (1934), “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 198, gennaio 2023, pp. 77-85 | PDF of the article