Towards an Edition of the Atlas. Gertrud Bing’s Unpublished Notes on the Mnemosyne Atlas Panels

Gertrud Bing. Introduction, first Edition and Translation by Giulia Zanon

Abstract | Versione italiana

§ Introduction

§ Gertrud Bing’s Unpublished Notes on Mnemosyne Panels [WIA.III.108.2]

Introduction

Giulia Zanon

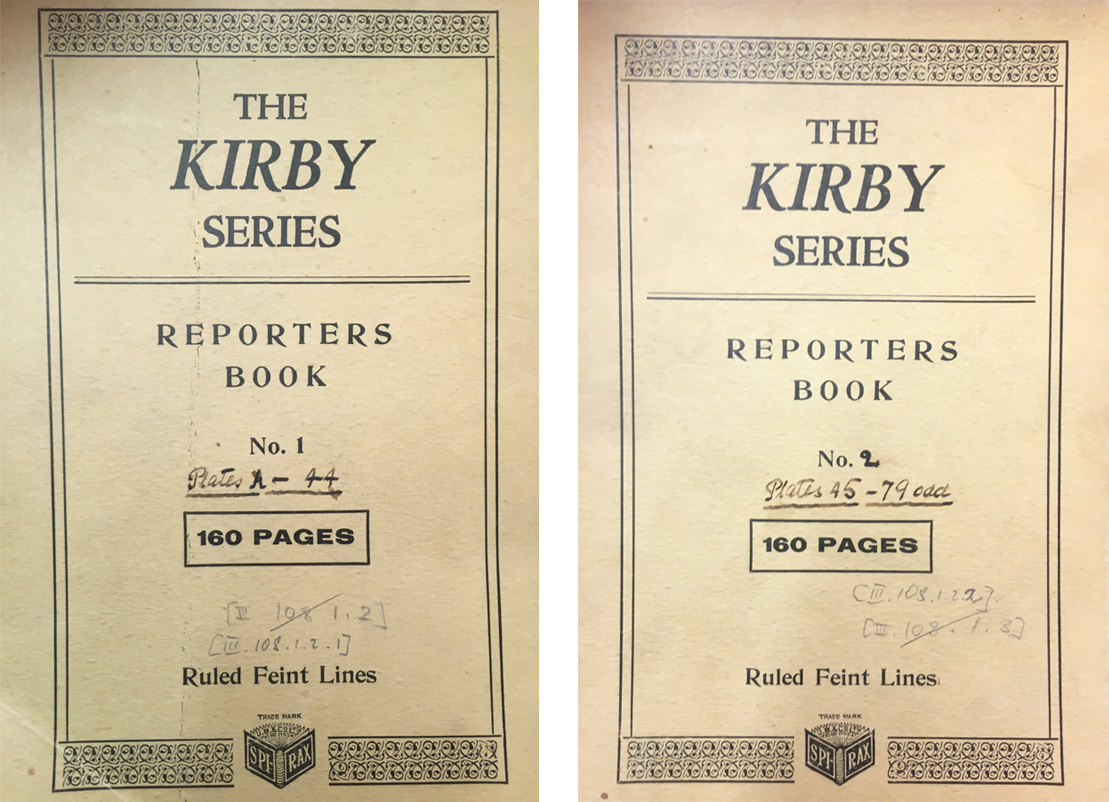

Two Notebooks

Gertrud Bing’s two Kirby Series notebooks.

Under the file number WIA III.108.1.2, the archive of the Warburg Institute in London contains two small, ruled ‘reporters book’ notebooks marked “The Kirby Series”. They are identical, and both are the size of a notepad, roughly A5 size. On the cover of each is a title written in pen in English: “No. 1. Plates A–44” and “No. 2. Plates 45–79 odd”. As the reference to “Plates” suggests, the contents refer to Aby Warburg’s Atlas, whose Panels are known to be numbered progressively from 1 to 79, with some omissions, after the initial block of plates labelled A, B, and C. Inside, the notebooks contain a series of pencilled notes in Gertrud Bing’s clear handwriting, arranged according to the sequence of the Panels. Contrary to the titles on the cover, the language used inside is German. The notes form a kind of synopsis of each Panel, with instructions – mostly addressed by Gertrud to herself – for the completion, editing, and publication of the Mnemosyne Atlas.

Prelude: A Disrupted Project

Aby Warburg’s sudden death on 26 October 1929 marked the abrupt end of the period considered to be the peak of the scholar’s intellectual production (as testified in Pasquali [1930] 2022). It was a period of fervent study and prolific activity whose brightness had finally dispelled the shadows and defeated the aporia of Kreuzlingen, the Swiss sanatorium from which Warburg had returned in 1924 as a redux, with the lucid will to give a decisive turn to his intellectual action. He started with the construction of the library, which, with its elliptical hall, immediately emerged as a space with clear ideological connotations, “a rotating turret of observation and reflection” (From the Arsenal to the Laboratory (1927), in Warburg [1927] 2012, 119; about the construction of the Bibliothek Warburg see Settis [1985, 1996] 2022, Calandra di Roccolino 2019, Calandra di Roccolino 2014).

Warburg’s sudden death disrupted the joyous aftermath of an extensive journey in Italy undertaken by Warburg and Gertrud Bing in late 1928 and early 1929. This was the trip that provided an opportunity to put the “Warburg method” to the test (think, for example, of the great lecture at the Hertziana Library in Rome in January 1929; see De Laude 2014; Sears 2023) and solidified Warburg’s awareness of the absolute importance of his own cultural mission (“I am growing in the idea that my method has been well received and that it will have consequences”, Warburg wrote: Diario romano, 49). The journey had also provided the impetus for the completion of the Mnemosyne – the great figurative Atlas that follows the karst phenomenon of the expressive formulas of antiquity – which, in the two years preceding the trip, had become Warburg’s greatest, most important, and, above all, most urgent work.

The urgency to conceive and publish the Atlas is evident in the extensive notes left by Warburg and in his diaries from those years, including the Tagebuch of the Warburg Library, which was compiled by Aby Warburg, Gertrud Bing, and Fritz Saxl starting in 1926 (and by Warburg and Bing alone after 1928). Reading through the pages, on which ideas and discoveries were recorded from year to year, the presence of Mnemosyne begins to emerge more and more clearly. At first contemplated as an idea, the Atlas gradually becomes the ultimate goal of research and the mission of a lifetime. Phrases such as “… Mnemosyne will follow”, and “It is the most profound aid to achieving our goal: Mnemosyne” (Diario romano, 52, 65) become increasingly frequent. This impulse towards Mnemosyne in the diaries from 1928 and 1929 implies very clearly and in every entry a ‘we’. The presence of “College Bing”, “Herr Bing”, and “Bingius” – some of the nicknames used by Warburg in letters and diaries – is always highlighted and maintained in the foreground. In the Atlas-project, Gertrud Bing is not a mere helper, although this is the role to which she has for too long been relegated by basically misogynistic literature that has occasionally made her the ‘secretary’ and at most the ‘assistant’. Rather, she is a true co-author, a faithful companion in the period that Bing herself would define as “such a high point in the professor’s life, a wonderful conclusion and cathartic synthesis of his whole heroic and eternally combative life” (letter from Gertrud Bing to Rudolph Wittkower, 12 December 1929 [WIA GC]).

On 26 October 1929, Aby Warburg died. This interrupted a major project, the Mnemosyne Atlas, which at last seemed to be close to publication. A month later, in a letter addressed to the art historian Ulrich Middledorf, Gertrud Bing wrote:

Das letzte Jahr den Atlas doch soweit gefördert hat, dass wir daran denken dürfen, ihn herauszugeben. Gerade in den letzten Wochen ist eine neue und ziemlich endgültige Fassung der Tafeln entstanden. An fertigem zusammenhängendem Text ist zwar nicht sehre viel vorhanden, immerhin aber ist der Nachlass an Aufzeichnungen und Notizen so unendlich groß, dass wir hoffen dürfen, mosaikartig den ganzen Kommentar mit seinen eigenen Worten zusammenstellen zu können. Über die Anlage des Ganzen z.B. was die Hinzufügung von Dokumenten betrifft, sind wir auch ziemlich genau unterrichtet. Die “Mnemosyne” werden Professor Saxl und ich zusammen herausgebende […].

Over the past year, the Atlas has progressed to the point where we are thinking of publishing it. In the last few weeks a new and rather final version of the Panels has been composed. Although there is no really finished and coherent text, the body of notes and annotations is so vast that we can hope to put the whole commentary together as a mosaic of his own words. We are also well aware of the structure of the work as a whole, e.g. with regard to the addition of material. Professor Saxl and I will be the editors of Mnemosyne […] (Letter from Gertrud Bing to Ulrich Middledorf, 25 November 1929 [WIA GC], author’s translation).

These lines are taken from a letter whose content is comparable to many others in the dense correspondence of the period. Faced with expressions of grief at Warburg’s death, we find in Bing no retreat into despondency but rather an outburst of positive reaction in the name of conscience and responsibility towards that bewildering but fertile legacy still in the making, which had yet to bear its best fruit. Warburg’s death certainly marked a stopping point, but what had not died was the sense of urgency clearly expressed in Bing’s words: The Atlas can – must – be published. The unflagging energy of the fire that Warburg kindled was alive and well, and Gertrud Bing’s clear, rational will was determined to carry on the most important project of all: Mnemosyne.

There are two highly important pieces of information regarding the possibility of publishing the Atlas that can be gleaned from the letter to Middledorf: 1) The state of near-completion of the last version of the Atlas, which was composed in the last weeks of Warburg’s life upon his return from his trip to Italy in the autumn of 1929; 2) The existence of a precise, methodologically ordered structure, which Warburg’s collaborators (particularly Bing) had mastered, and the possibility of constructing a commentary on the work using Warburg’s “own words” thanks to the vast corpus of notes on the subject.

The urgency of the publication of Mnemosyne, and at the same time, the difficulties that arose after Warburg’s death, are evidenced by a large number of letters and the drafting of a new publishing contract (as Bing wrote in the Tagebuch on 8 October 1929: “Long letter to Teubner. [...] Mnemosyne has been announced”, GS Tagebuch, 544; see also Centanni 2022a, 325). On 9 December 1929, after Warburg’s death, Fritz Saxl received a letter from Victor Fleischner, director of the Heinrich Keller publishing house, who was a pioneer in the use of collotype and specialised in art publications:

Nach meinen Notizen schätzen Sie den Umfang der Warburgschriften:

Kleine Schriften ca. 400 Seiten

Ungedruckte Vorträge ca. 150 Seiten

Tagebuch, Briefe, Aphorismen ca. 400 Seiten

Illustrationen insgesamt 300 Abbildungen

Atlas ca. 400 Seiten und 300 Liichtdrucktafeln

According to my notes, your estimate for the volume of Warburg’s writings:

Selected Writings, about 400 pages

Unpublished lectures, about 150 pages

Diary, letters, aphorisms approx. 400 pages

Illustrations 300 illustrations in total

Atlas approx. 400 pages and 300 collotype plates (Letter from Victor Fleischner to Fritz Saxl, 9 December 1929 [WIA GC], author’s translation).

Gertrud Bing’s determination to publish Warburg’s work did not only concern the Atlas; it was primarily focused on a conceptually and editorially easier operation: the publication of the volume of edited essays. Ultimately, the collection was published by Teubner and edited by Bing and Fritz Rougemont (on the forgotten figure of Fritz Rougemont, see A forgotten essay by Fritz Rougemont on Warburg and the use of “bibliophily” as a scientific tool, published in this issue of Engramma). The republication of the edited essays certainly represented a first, fundamental step in the valorization of Warburg’s work, but as fate would have it, the Gesammelte Schriften (the “Selected Writings” to which Fleischner refers in his letter) only became available in 1932, at the dawn of the rise of National Socialism and the subsequent tragic diaspora of German intellectuals from the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (this tragic state of affairs is illustrated by Mario Praz in his review of the collection of Warburg’s writings: Praz [1934] 2022). Moreover, October 1929 marked the beginning of a very difficult period of uncertainty, economic even more so than political (as Monica Centanni notes: “Significant, yet not sufficiently highlighted in the critical literature, is the coincidence between the outbreak of the Wall Street crisis (29 October 1929), the date of Aby’s death from a heart attack (26 October 1929): Centanni 2022a, 343), that jeopardized all the plans of the KBW and turned the fate of the Warburgkreis upside down (see Burkart [2000] 2020). The intellectuals who had gathered around the Hamburg library migrated to London, where everything changed. The name was changed from KBW to Warburg Institute, the language of scientific communication went from German to English, and the hierarchies and relationships within the group were altered (see Centanni 2022b, Centanni 2020, Takaes 2020, Takaes 2018).

Nonetheless, the newly founded Warburg Institute continued to focus on the publication of everything left behind, in primis Warburg’s unpublished works. This was stated in the Institute’s first annual report (1934–1935):

Before new English works are taken in hand, we are however faced with the task of completing those already begun in Germany. An essential piece of work of this kind we consider to be the edition of Professor Warburg’s collected works, two volumes of which appeared earlier […]. An “Atlas”, which will contain his hitherto unpublished work on “the History of Expression and Gesture in the Renaissance”, with special reference to the influence of classical sources, is being prepared by Dr. Bing (The Warburg Institute Annual Report 1934-1935, London 1935, 8).

Before new research could begin in the new English institute, it was essential to publish everything that was in the pipeline in the later years in Hamburg. First and foremost was the Atlas. The annual report indicates that around 1935 Bing was still actively working on the section of an “Atlas” on the “History of Expression and Gesture in the Renaissance”. One can imagine Bing intent on picking up the pieces of images and words that Warburg had left for Mnemosyne, delicately shaping and framing them to form “a mosaic of his own words”.

The notebooks published here for the first time have no precise date. As we have seen, the materiality of the supports, which are certainly of British manufacture, and the hand-written English titles on the covers (the use of English seems to be conditioned by the language on which the graphic design of the covers is based) allow us to date the notes with a good margin of certainty, placing them after the move across the Channel. The terminus post quem of 1932 is confirmed by two internal dates: the references to the Gesammelte Schriften, published in Leipzig in 1932, and the reference to Jean Seznec in the note to Panel 27, which provides another clue for dating the notebooks to the mid-1930s. The two notebooks thus provide further evidence that, as the first report of the Warburg Institute attests, Gertrud Bing took over the Atlas material around 1935 in preparation for the Atlas’ publication.

The Commentary Structure

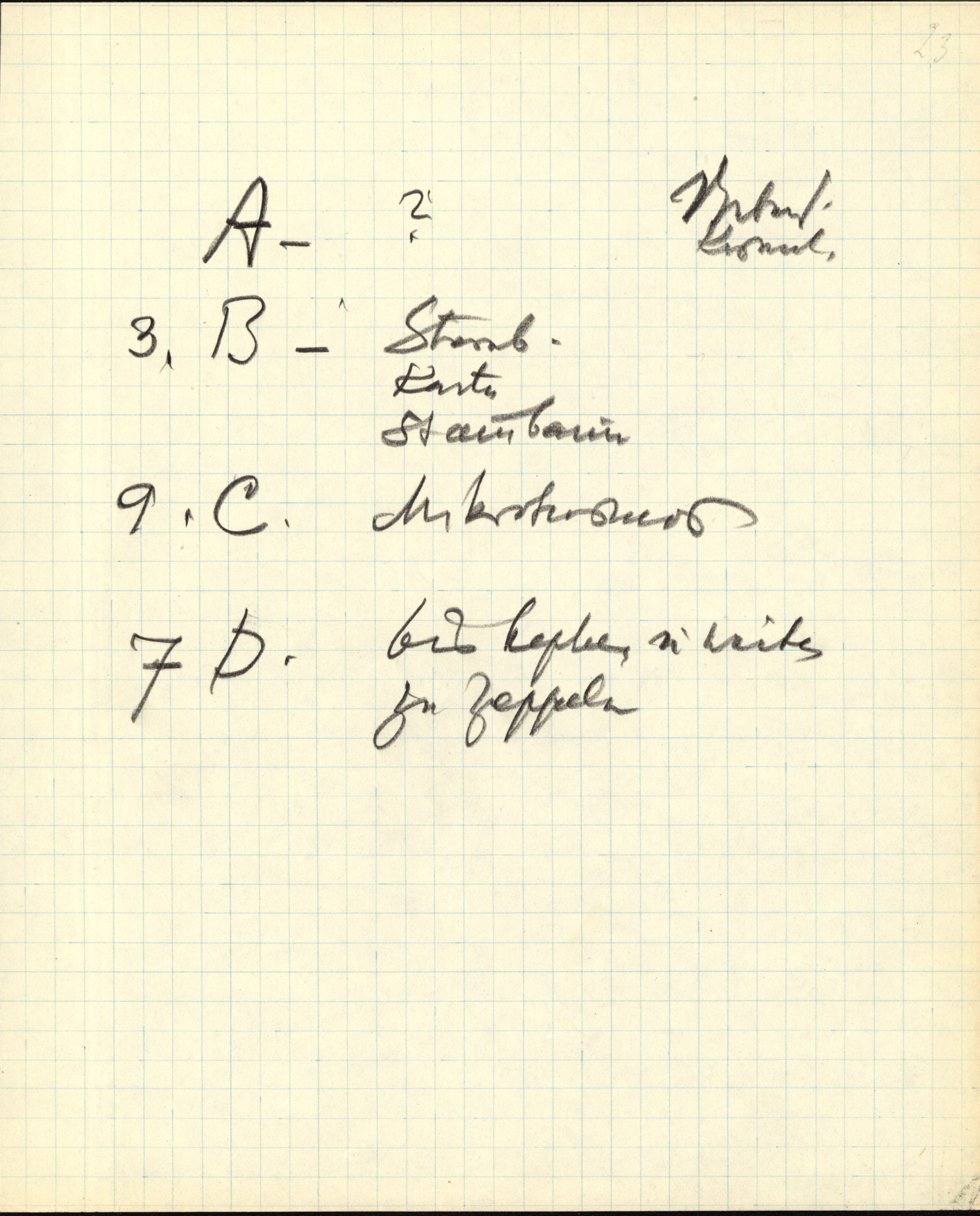

2 | Aby Warburg’s notes on the structure of Mnemosyne, 1929 [WIA III.102.6.2, f.23]. Photo: The Warburg Institute.

The two notebooks examined follow the numbering of the Panels in the last photographically documented version of the Atlas (the so-called Final Version, dated autumn 1929). Bing writes commentaries on all the plates except for Panel 59 and Panel B, to which is dedicated a laconic ‘B’ heading in pencil, followed by a few pages that were apparently left blank to be filled in later.

One interesting detail is the presence of a Panel D. Under the title “Oriental (Babylonian) Divinatory Practices”, Bing’s notes refer to the clay liver of Bogazköy, the bronze liver of Piacenza, the Boundary stelae, and the Babylonian Kudurru. All images are found in Panel 1 of the Atlas. Thus, there is no Panel D in the documented version of the Atlas, but the contents of the Panel correspond exactly to Panel 1 and replace it in the sequence.

However, the intention to include a panel called ‘D’ in the sequence can already be read in a series of notes in Warburg’s own hand that were dated 1929 and related to the structure of Mnemosyne:

A – ?

3. B – Sternb

Karte

Stammbaum

9. C – Mikrokosmos

7. D – bis Kepler u. weiter zu Zeppelin

[WIA III.102.6.2, f.23].

According to this note [Fig. 2], the sequence of the opening panels should have flowed, leaving room for the inclusion of an initial Panel A, thus changing the titles of the first three Panels (A>B; B>C; C>D). Instead, in her notes, Bing proposes to include what we know as Panel 1 in the ‘orientation’ blocks A, B, and C (on the genesis and structure of the ABC block, see the seminal contributions De Laude 2015 and Seminario Mnemosyne 2015).

The most definitive confirmation of the existence of Panel D in the Bilderatlas project and of the incipit nature of Mnemosyne’s first Panels comes from Warburg, in a note a few days before his death:

Circa 80 Gestelle mit circa 1160 Abbildungen. Werde circa 6 Tafeln zur Erkenntnistheorie und Praxis der Symbolsetzung aufstellen (A, B, C, D…).

About 80 panels with 1160 pictures. I set up about 6 panels for a theory of knowledge and a practice of symbolisation (A, B, C, D,...) (Entry of 20 October 1929, GS Tagebuch, 551, author’s translation).

This statement is an essential contribution to the reconstruction of the history of the Atlas project as it testifies to: 1) the desire to include in Mnemosyne some six panels, identified by alphabetical letters rather than numbers; and 2) the theoretical nature of these ‘alphabetical’ panels, which must be read as the thesis that the Atlas seeks to test and as the elaboration of a gnoseological theory and its application through the “practice of symbolisation”. Warburg’s definition of the Panels “A, B, C, D,…” deserves further elaboration but will not be addressed here; it is however relevant to note that “Zur Erkenntnistheorie und Praxis der Symbolsetzung” is one of the titles of the introductory pages to the Geburtstagsatlas, the “Birthday Atlas”, the private edition of the Atlas prepared in 1937 by a young Ernst Gombrich (for the edition and history of the Geburtstagsatlas see, among others, Seminario Mnemosyne 2023a; for an index of contributions on this subject see Seminario Mnemosyne 2023b).

Another element worth noting is the presence of a page of notes dedicated to Panels 1-8, with each panel corresponding to a title. It is a kind of summary for the “Antike Vorprägungen”, which presents the themes: catastrophization and the belief in the stars to affect triumphal pathos, the passage through the pathetic formulae of the kidnapping and the lament, the energetic inversion between pain and fury, the mystery cults. In the economy of the commentary, this passage confirms the plan to treat the “pre-impression of the Antiquity” as a single block within the Atlas – a chapter devoted to the “original expressions of gestural language”, the repertoire of models on which the tradition of the ancients could draw during various epochs. The only panel that does not have an assigned theme is Panel 1, but given the presence of the previous Panel D/Panel 1, this fact might simply suggest that Bing wanted to insert a new Panel 1 (on this point, see Gertrud Bing’s letter to Middledorf, particularly the passage that reads: “We are also quite aware of the structure of the whole work, e.g. with regard to the addition of materials”).

The style of the annotation is that of a note. It is a dry way of writing that uses shorthand signs (‘+’, ‘–’, ‘→’) and is obviously addressed more to Bing herself than to a hypothetical reader. In the working state of someone who is trying to regain familiarity with the Panel material after five years and a traumatic move to London, Bing does not spare herself questions, doubts, or personal comments, and vows to study certain topics in greater depth. The questions raised are on several levels. Some questions concern the assembly: “Why here?” she asks about the depiction of the Muses in Panel 2; “Does the leaf from Reg. lat. 1283 belong on the next page?” she asks about Panel 21. Other doubts concern the nature of the materials. With regard to the two maps shown in Panel A, the celestial and the geographical, Bing asks why “an older map” and “a normal map”, respectively, were not used. Other questions concern the meaning of the composition and the different degrees of conceptual complexity of the juxtapositions. Panel 4 reads “[…] There is the river god (connection with Ariadne?)”; on Panel 41 she asks: “Is Virgil understood as the master of all the pathos of battle and triumph, or only as the source of the Venus Virgo?”. Bing not only asks questions but also expresses her perplexity about certain passages: “I do not understand this Panel in detail at all” in reference to Panel 34; she reiterates her willingness to research certain topics in more detail (“I must first research all the other images” is written for Panel 60).

Bing’s uncertainty on some points becomes a valuable hermeneutic tool because it explains the need to unravel the hermeticity of the most well-known meagre notes left by Warburg and published in various editions of the Atlas (from Rappl et al. 1994 onwards and, above all, Seminario Mnemosyne 2012). If the Mnemosyne project is to be seen as rhizomatically extended and intricately developed in the mind of its creator and its completion thought of as only possible thanks to the patient process of maieutics and spatial organization of the flow of mental images prematurely interrupted in October 1929, then Bing’s questions and doubts, which were close to Warburg’s during the most intense phase of his elaboration of the Mnemosyne Panels, constitute an echo of this difficult and tormented intellectual gestation.

In Gertrud Bing’s notes, distinctly Warburgian terms recur. A good example comes from the notes relating to Panel 21, which were dedicated to the Arabic version of the planets ‘on the way to magical practice’. The ancient deities in oriental garb are:

Ausgesucht nach ihrem Erinnerungsgewicht. Nachlebe Wert. Engramm. Engraphische Energie.

Chosen according to their weight on Memory. Afterlife value. Engram. Engraphic energy.

As is well known, Warburg borrowed the term “Engram” from Richard Semon’s studies on memory. According to the definition proposed by the biologist in Die Mneme (1904), the engram is the trace of a memory or experience imprinted in an individual’s neural network. Warburg took Semon’s theory and transferred it from biology to his field of study, namely cultural history.

The term thus recurs in some passages of Warburg’s writings, especially in the last period of his life. Some of such passages read: “The metamorphosis motif taken from Ovid […] has been modified, but the effect remains as a mnemonic engram linked to stimuli in the general pathosformel of the figures” (Diario romano (1929), 68-69); “It seems to me that a relief with the emperor riding impetuously over dead enemies, as it found its barbaric expression in Valente’s medal, is an engram that resists stylistic transformation of an ethical kind” (L’Antico romano nella bottega di Ghirlandaio (1929), in AWM II, 688); “The Eroici Furori cling like an engram!” (Syderalis abyssus: Giordano Bruno (1929), in AWM I, 421). The trace of the engram “persists”, “resists stylistic change”, “clings”. Note how in all these passages, the engram is always linked to the act of “resisting” transformations and changes relevant to the period and context. The sign, once deeply inscribed, cannot be washed away by the waters of time. These passages highlight, in nuce, the concept and mechanism of Nachleben, the survival and re-emergence of the ancients through latencies, karst paths, and mutations.

To better understand the meaning and dynamics of the engram’s operation, it is useful to consider Bing’s note on Panel 21 in its entirety. It suggests that the planets are “chosen according to the weight they have on the memory”. For this passage, it is useful to question the theory of Charles Darwin, another scholar from whom Warburg drew important insights. Warburg first read The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals in the Biblioteca Nazionale in Florence during his stay with August Schmarsow in 1888 and noted in his diary: “At last a book that is useful to me”. In the field of cultural memory, too, the “stronger” element prevails as it is more capable of adapting to the new context, like the planetary gods of Arab culture. This agonal element of a “struggle for survival” in which the one who “has the most weight in memory” prevails is a Darwinian feature on which the theoretical structure of the Mnemosyne Atlas is based. The fact that images and concepts are chosen, as Bing points out, “according to the weight they have in memory” cannot therefore go unnoticed. As Antonella Sbrilli writes:

L’impronta darwiniana (col suo portato di concetti quali sopravvivenza, variazione, ereditarietà) è stata riscontrata nel riconoscimento dell’“agonismo delle dinamiche culturali”, della “mimetica capacità di persistenza” di immagini e segni, della forza di sopravvivenza intrinseca che alcune forme e soggetti della tradizione figurale dimostrano nel corso del tempo e dello spazio.

The Darwinian imprint (with its bearing of concepts such as survival, variation, heredity) has been found in the recognition of the “agonism of cultural dynamics”, the “mimetic capacity for persistence” of images and signs, the intrinsic survival force that certain forms and subjects of the figural tradition demonstrate in the course of time and space (Sbrilli 2004, 22, author’s translation).

Interesting in Bing’s notes is the use of the term “engraphic”. “Engraphic energy” is another term derived from Semon’s work, Engraphische Wirkung der Reize auf das Individuum (“The Engraphical Effect of Stimuli on the Individual”) and is the title of the second chapter of Mneme. The term “engraphic energy” never occurs in Warburg’s corpus, but by rereading Semon’s definition, we can understand Gertrud Bing’s choice to evoke the idea of “engraphic energy” for Mnemosyne:

Ich bezeichne diese Wirkung der Reize als ihre engraphische Wirkung, weil sie sich in die organische Sustanz sozusagen eingräbt oder einschreibt. Die so bewirkte Veränderung der organischen Substanz bezeichne ich als das Engramm des betreffenden Reizes, und die Summe der Engramme, die ein Organismus ererbt oder während seines individuellen Lebens erworben hat, bezeichne ich als seine Mneme.

I call this effect of the stimuli their en graphic effect, because it engraves or inscribes itself, so to speak, in the organic substance. I call the change in the organic substance brought about in this way the engram of the stimulus in question, and the sum of the engrams that an organism has inherited or acquired during its individual life I call its mneme (R. Semon, Die Mneme, Leipzig 1904; author’s translation).

Applying this biological theory to the field of the transmission of forms and ideas, we can say that the “engraphic effect” or “engraphy” is the first phase of the impression of a stimulus in collective and individual memory. From this impression, a mutation of the “organic substance” of culture itself results, a modification that can be defined as an “engram”. Finally, the set of “engrams”, inherited from tradition or acquired through external transplants, constitutes the historically connoted “cultural memory”. Bing’s chosen expression “engraphic energy” constitutes an important reading of Semon’s lesson and its Warburgian declination: it is the phase of first impression that contains the energetic potential of becoming of forms and concepts and the promise of their reappearance, forever new.

Mnemosyne Atlas and Warburg’s Writings: A single Corpus?

Bing’s notes often present specific references to various texts, sources, and critical contributions, motivating the presence of an image or series of images in the Panel (as is well known, one of the cornerstones of the method of Aby Warburg, whose one of his mottos was “Zum Bild, das Wort!”). The references are of a different nature. Bing refers to literary sources, such as the letters of Alessandra Macinghi Strozzi (whom Warburg had sent to him by Olschki during his stay in Rome, although he never mentions him directly in his texts), that testify to the new interest in a representation of restrained pain, as expressed in Panel 31; or, for Panel 40, La strage degli innocenti, a poem by Gianbattista Marino which for Warburg “is an excellent example of this bombastic baroque style, which expends its energies on the crassest of painted depictions of human violence and states of arousal” (The Entry of the Idealizing Classical Style in the Paintings of Early Renaissance, Warburg [1914] 2001, 23). Another reference is to contemporary scholarly essays, which are to be considered an essential methodological reference for understanding some of the thematic nodes of the Atlas. For example, James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (London 1915) was mentioned in reference to Panel 41a and Laocoon was called a “God-priest, King-priest, priest-sacrifice”.

In addition to sources and scholarly essays by various authors, there are explicit references to Warburg’s essays, which are referenced according to Gesammelte Schriften, the complete collection of edited essays, published by Teubner in 1932 and edited by Bing and Rougemont. See, for instance, the reference in the note to Panel 34: “Below, the peasants at work, see Gesammelte Schriften. […] Alexander, see Gesammelte Schriften”; or in the note to Panel 39: “Engraving of Venus with Dancing Couple (see Gesammelte Schriften) […] Tarsia, see Gesammelte Schriften”; or in the note to Panel 43 “Ghirlandaio. Mirror of the soul, see Gesammelte Schriften essays”, etc. As we have seen, the reference to the Gesammelte Schriften is also an important element for the dating of the notes, as it is the main confirmation of 1932 as the post quem date of the writing of the notes.

However, the references to Warburg’s writings do not end with references to published essays. For example, take Panel 79, in which Warburg constructed a montage of photographs documenting the most recent chronicle, the Eucharistic procession of Pope Pius XI in St Peter’s on 25 July 1929. Of the montage, Bing wrote: “In the centre: the Pope as news (Cf. Doktorfeier)”. “Doktorfeier” is a reference to an unpublished Warburg text, the Celebration Speech for Three Doctorates, which was delivered in Hamburg on 30 July 1929, shortly after Warburg and Bing’s return from the Italian trip (WIA.III.112, the Italian translation now in AWO I.2, 903-910). In the text, Warburg refers to a “salad of pictures” that we find in the montage of Panel 79, in the middle band on the right: this is the illustrated supplement of the “Hamburger Fremdenblatt” of the previous day. For reasons of typographical economy and layout, the iconographic section on early twentieth-century newspapers was concentrated on one or more pages reserved for illustrations. The result was a montage of images juxtaposed in a completely arbitrary manner, with jarring contrasts and unexpected parallelisms. In his address to the postgraduates, Warburg presented the work, which “at first glance seems to be about a helpless abundance [of images]”, as a cross-section of the “problematic emotional and intellectual situation” of the reappearance of the antiquity in the contemporary; it is symptomatic precisely because it is by no means accidental. Among the winners of swimming competitions, racehorses, and the members of the city’s golf club, we also see, for example, the Pope “as news”:

Pope Pius XI with the vestments and monstrance being led into St Peter’s Square in Rome on 25 July […]. As his writings on mountaineering show, Pope Pius XI was an excellent and accomplished climber. Yesterday he left Hamburg after a long stay, accompanied by the Archbishop of Osnabrück and the German Nuncio Pacelli. Before his departure the Pope had breakfast with the director of Hapag Cuno and then visited Hagenbeck […] (AWO I.2, 905-908; author’s translation).

A few lines earlier, the Doktorfeier also shows Warburg’s clear intentions regarding the KBW’s scientific agenda:

The illustrated journal supplement I have provided is not merely intended to add new material to a somewhat rhapsodic conversation, but has a more ambitious purpose. On this solemn evening, it is intended to help justify the mission of the Warburg Library. […] What the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg should do is the European dyspepsia of the intellectual heritage that has been at work in the Mediterranean from the earliest times to the present (AWO I.2, 903; author’s translation).

In these few lines, one can read a full awareness of the ambitious aim of the Mnemosyne project. Bing’s note on the Panel referring to the unpublished lecture is therefore not surprising. It may have been useful in interpreting the meaning of Panel 79, but it could also have been included in a wider project to publish Warburg’s unpublished writings.

In general, Bing’s notes prove that in addition to the project of compiling a commentary on the Mnemosyne Panels following certain thematic and lexical traces left by Warburg, there is full awareness of the fact that the Atlas should be included in the corpus of Aby Warburg’s production, including his unpublished works and thus going beyond the essays included in the Gesammelte Schriften.

However, the Atlas is certainly the most valuable among Warburg’s unpublished works. In Bing’s notebooks, the use of “Seite” (in Panel 21: “Does the sheet from Reg. 1283 belong with the next page?”), and of “Blatt” (in Panel 26: “Tabula Bianchini and the graph with the schematic comparison are relevant to Panel 27 – Schifanoja). provide important evidence that the edition is conceived as a series of “pages” and “sheets” to be moved and rearranged until a definitive and readable arrangement is found. Once again, Bing’s notes on the Mnemosyne Panels confirm that the Atlas is conceived exclusively as a book in which the tables are to be arranged alongside commentaries; it is constructed “like a mosaic of Warburg’s own words”.

Gertrud Bing’s unpublished notes on the panels of the Mnemosyne Atlas [WIA.III.108.2]

Gertrud Bing, first edition by Giulia Zanon

My warmest thanks to Monica Centanni and Maurizio Ghelardi for their linguistic and conceptual revision and exchange during the writing of this contribution.

Versione italiana

Panel A

Panel B

Panel C

|

[C] Stages of overcoming the fear of the cosmos. |

Panel D [Panel 1]

|

[D] Oriental (Babylonian) practice of divination |

Panels 1-8

Panel 2

|

[2] The rising sun (Helios = Apoll) |

Panel 3

|

[3] Unrolling + crowding the globe |

Panel 4

|

[4] Sarcophagi (i.e. mythology + cult of the dead) |

Panel 5

|

[5] Cave of the Magna Mater |

Panel 6

|

[6] Cult – Mysteries |

Panel 7

|

[7] Subjugation and upward countermovement. |

Panel 20

|

[20] Greek faith in the stars in Arabic guise |

Panel 21

|

[21] Arabian planets (as Monstra?) on the way to magical practice. |

Panel 22

|

[22] Spain transmits Arabic science as magical practice (Alfonso El Sabio, Toledo, thirteenthth century at the time of Frederick II in Sicily). |

Panel 23

|

[23] Direct transmission to central Europe. |

Panel 23a

|

[23a] Fates of destiny |

Panel 24

|

[24] Nordic images of the children of the planets |

Panel 25

|

[25] The aulic style in movement in the representation of cosmological themes. |

Panel 26

|

[26] Tabula Bianchini and the graph with the schematic comparison belong with Panel 27 – Schifanoja. |

Panel 27

|

[27] Here I note that Jupiter is omitted from the Panel. |

Panel 28/29

|

[28/29] Connection to the previous panel is the third band of Schifanoja: ‘life in motion’. |

Panel 30

|

[30] The stylistic level of the images prior to its climax (a point maintained throughout the elaboration of the Atlas). |

Panel 31

|

[31] What do Florentines look for in Flemish painters? Nordic mirror of the soul |

Panel 32

|

[32] Coarse humour – grotesque movement –covetousness of the rough man towards the woman |

Panel 33

|

[33] The contribution of the North continues |

Panel 34

|

[34] Contribution of the North. |

Panel 35

|

[35] Equally incomprehensible in the association of ideas. |

Panel 36

|

[36] Pesaro 1476 |

Panel 37

|

[37] Liberation of the body from the constraint of clothing. |

Panel 38

|

[38] The pictorial context and style of the “Otto prints” and early Florentine copper engravings, “The liberation of temperament and its taming”. |

Panel 39

|

[39] The Realm of Venus |

Panel 40

|

[40] The frenetic movement, the rapture, the thiasotic procession, originate from the Bacchic circle as seen in the medallions with Bacchus in the Medici Palace and the engraving with Bacchus. The exuberant rapture. Ovid’s Metamorphoses at the Villa Farnesina: friezes as a passing procession. The mythical background of the idyllic tale is revealed in a gestural language charged with pathos. |

Panel 41

|

[41] Excluding the desperate mother of Panel 40: the woman as the one who performs the sacrifice + object of the sacrifice, executioner + saviour |

Panel 41a

|

[41a] Laocoon, God-priest, King-priest, priest-sacrifice, etc. |

Panel 42

|

[42] Lamentation on the Dead God. |

Panel 43

|

[43] Ghirlandaio |

Panel 44

|

[44] Ghirlandaio |

Panel 45

|

[45] Ghirlandaio |

Panel 46

|

[46] Tornabuoni – Ninfa |

Panel 47

|

[47] Tobias – Judith (Salome) |

Panel 48

|

[48] Fortune |

Panel 49

|

[49] Mantegna is a luminous as Piero. |

Panel 50/51

|

[50/51] Fluttering robes + dance script |

Panel 52

|

[52] The ethical side of the Roman pathos: Trajan’s Justice – Scipio’s Continence. |

Panel 53

|

[53] Descendants of the Muses |

Panel 54

|

[54] Chigi |

Panel 55

|

[55] The extension of the feeling for the cosmos to nature (no longer just the higher regions). |

Panel 56

|

[56] Rise + fall, upper + lower, coronation + downfall. The aspiration and its reverse, the raising of the spolia becomes the erection of the cross in Filippino Lippi, |

Panel 57

|

[57] Migration of the planets to the north. See the essay. |

Panel 58

|

[58] Dürer + astrology |

Panel 60

|

[60] The series that begins now is linked to the representation of the triumphal procession – Triumph. The procession during festivals that develops into a frontal stage. At the same time as a mythological figure, Neptune appears (and as author Virgil with “Quos ego”), symbolising the progressive dominion over the sea in the age of discovery. |

Panel 61-64

|

[61-64] I think this [Panel] should become something like “The Realm of Neptune” (cf. “The Realm of Venus” in the fifteenthh century). Link to “Quos ego”. Or also: Neptune + his entourage. |

Panel 70

Panel 71

|

[71]The election of the hero by elevation on the shield. |

Panel 72

|

[72] The mystery of the liturgical supper. |

Panel 73

|

[73] This seems to me to consists of two parts: |

Panel 74

|

[74] Effective remote action |

Panel 75

|

[75] The “disinterested” consideration of the human body in contrast to: |

Panel 76

|

[76] Tobias’ motif becomes towards home |

Panel 77

|

[77] The entry of pathos formulas into the gestural language of everyday life. |

Panel 78

|

[78] Lateran Pacts: |

Panel 79

|

[79] The Mass as a claim to power. |

Bibliography

Sources

- AWM II

A. Warburg, Fra antropologia e storia dell’arte. Saggi, conferenze e frammenti, a cura di M. Ghelardi, Torino 2021. - AWO I.2

A. Warburg, La rinascita del paganesimo antico e altri scritti (1917-1929), a cura di M. Ghelardi, Torino 2007. - Diario romano

A. Warburg, G. Bing, Diario romano (1928-1929), a cura di M. Ghelardi, Torino 2005. - Rappl et al. 1993

W. Rappl et. al. (hrsg. von), “Aby Warburg Mnemosyne”. Eine Ausstellung der Transmedialen Gesellschaft Daedalus in der Akademie der bildenden Künste (Wien 25. Januar-13. März 1993), Hamburg 1994. - Seminario Mnemosyne 2012-

Seminario Mnemosyne, coordinato da M. Centanni, Aby Warburg. Mnemosyne Atlas, edizione digitale “La Rivista di Engramma” (2012-). - Warburg [1914] 2001

A. Warburg, The Entry of the Idealizing Classical Style in the Paintings of Early Renaissance, translated by M. Rampley, in Art History as Cultural History. Warburg’s Project, edited by R. Woodfield, London/New York 2001. - Warburg [1927] 2012

A. Warburg, From the Arsenal to the Laboratory, edited by C.J. Johnson and C. Wedepohl, “West 86th” 19/1 (Spring-Summer 2012), 106-124.

Bibliographical References

- Burkart [2000] 2020

L. Burkart, “Die Träumereien einiger kunstliebender Klosterbrüder...”. Zur Situation der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Bibliothek Warburg zwischen 1929 und 1933, “Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte” 63/1, 2000, 89-119; tr. it. di C. Giannaccini, “Le fantasticherie di alcuni confratelli amanti dell’arte...”. Sulla situazione della Biblioteca Warburg per la Scienza della Cultura tra il 1929 e il 1933, “La Rivista di Engramma” 176 (ottobre 2020), 145-198. - Calandra di Roccolino 2014

G. Calandra di Roccolino, Aby Warburg architetto. Nota sui progetti per la Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg ad Amburgo, “La Rivista di Engramma” 116, maggio 2014, 54-65. - Calandra di Roccolino 2019

G. Calandra di Roccolino, L’architettura come forma simbolica: Aby Warburg e il progetto della Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg ad Amburgo, “Humanistica” XIV, 1/2 (2019), 123-145. - Centanni 2022a

M. Centanni (ed. by), Aby Warburg and Living Thought, trans. by E. Thomson, Dueville 2022. - Centanni 2022b

M. Centanni, The Rift between Edgar Wind and the Warburg Institute, Seen through the Correspondence between Edgar Wind and Gertrud Bing. A Decisive Chapter in the (mis)Fortune of Warburgian Studies, “The Edgar Wind Journal” 2 (2022), 75-106. - Centanni, Sacco 2020

M. Centanni, D. Sacco, Gertrud Bing erede di Warburg. Editoriale di Engramma n. 177, “La Rivista di Engramma” 177 (novembre 2020), 7-13. - De Laude 2014

S. De Laude (a c. di), Aby Warburg, Die römische Antike in der Werkstatt Ghirlandaios. Traccia della conferenza alla Biblioteca Hertziana (1929), con una Nota al testo (e “agenda warburghiana”), “La Rivista di Engramma” 119 (settembre 2014), 8-29. - De Laude 2015

S. De Laude, “Symbol tut wohl!”. Il simbolo fa bene! Genesi del blocco ABC del Bilderatlas Mnemosyne di Aby Warburg, “La Rivista di Engramma” 125 (marzo 2015), 30-79. - Frazer 1915

J. Frazer, The Golden Bough, London 1915. - Pasquali [1930] 2022

G. Pasquali, A Tribute to Aby Warburg [Ricordo di Aby Warburg], first edition “Pegaso” II, 4, 1930, 484-495. First Eng. trans by. E. Thomson “La Rivista di Engramma” 114 (marzo 2014), 6-19, now in Centanni 2022a, 37-56. - Praz [1934] 2022

M. Praz, Review of Aby Warburg, Gesammelte Schriften [Recensione a Aby Warburg, Gesammelte Schriften], First Edition: “Pan” II (1934), 624-626; First trans. by E. Thomson, “La Rivista di Engramma” 119 (settembre 2014), 30-32; now in Centanni 2022a, 57-60. - Sbrilli 2004

A. Sbrilli, La miniera memetica di Warburg. Collegamenti fra Mneme, memi e capelli mossi, “La Rivista di Engramma” 37 (novembre 2004), 19-34. - Sears 2023

E. Sears, Aby Warburg’s Hertziana lecture, 1929, “The Burlington Magazine” 165 (August 2023), 852-873. - Seminario Mnemosyne 2015

Seminario Mnemosyne, Iter per labyrinthum: le tavole A B C. L’apertura tematica dell’Atlante Mnemosyne di Aby Warburg, “La Rivista di Engramma” 125, marzo 2015, pp. 6-17. - Seminario Mnemosyne 2023a

Seminario Mnemosyne, Ernst H. Gombrich, Geburtstagsatlas für Max M. Warburg (5 giugno 1937). Edizione e saggio introduttivo, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 206 (ottobre/novembre 2023), 145-195. - Seminario Mnemosyne 2023b

Seminario Mnemosyne, Geburtstagsatlas by Ernst H. Gombrich (1937). Index of materials published in Engramma (updated November 2023), “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 206 (ottobre/novembre) 2023, 207-209. - Semon 1904

R. Semon, Die Mneme, Leipzig 1904. - Settis [1985, 1996] 2022

S. Settis, Warburg continuatus [Warburg continuatus. Descrizione di una biblioteca], First edition “Quaderni storici” 58, a. XX, 1 (aprile 1985), 5-38; First edition of the Final Note: in Le pouvoir des bibliothèques. La memoire des livres en Occident, ed. par M. Baratin et C. Jacob, Paris, 1996, 150-163; now in Centanni 2022a, 171-230. - Takaes 2018

I. Takaes, “L’esprit de Warburg lui-même sera en paix”. A Survey of Edgar Wind’s Quarrel with the Warburg Institute, “La Rivista di Engramma” 153 (febbraio 2018), 109-182. - Takaes 2020

I. Takaes, “Il y a un sort de revenant”, “La Rivista di Engramma” 171 (gennaio-febbraio 2020), 97-112.

We present hitherto unpublished handwritten notes made by Gertrud Bing after the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg relocated to London, possibly in the mid-1930s. The notes, which were written in two notebooks now housed at the Warburg Institute Archive, provide a synopsis of each Panel of the Mnemosyne Atlas. They include indications for the completion, editing, and publication of the Atlas. In her Introduction, Giulia Zanon attempts to contextualise this invaluable testimony through the study of letters and documents, dating from the final months of 1929, which were for both Warburg and Bing the most intense and productive period of work on the Atlas. She also considers the period following Warburg's death and the subsequent abrupt interruption of the Atlas project. The aim of this contribution is to emphasise the considerable significance of this document both for the hermeneutics of Mnemosyne and its publishing history. It constitutes evidence of the unwavering commitment to publish the Bilderatlas as part of a larger project to publish Warburg’s corpus.

keywords | Gertrud Bing; Aby Warburg; Mnemosyne Atlas; Gesammelte Schriften; Teubner.

questo numero di Engramma è a invito: la revisione dei saggi è stata affidata al comitato editoriale e all’international advisory board della rivista

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: G. Zanon, Towards an Edition of the Atlas. Gertrud Bing’s Unpublished Notes on the Mnemosyne Atlas Panels, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 211, aprile 2024, pp. 19-55 | PDF