Who is Anna?

You are Anna!

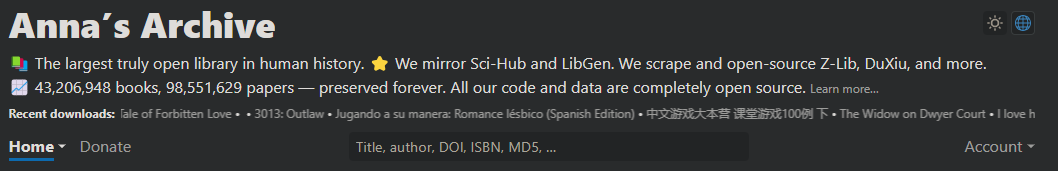

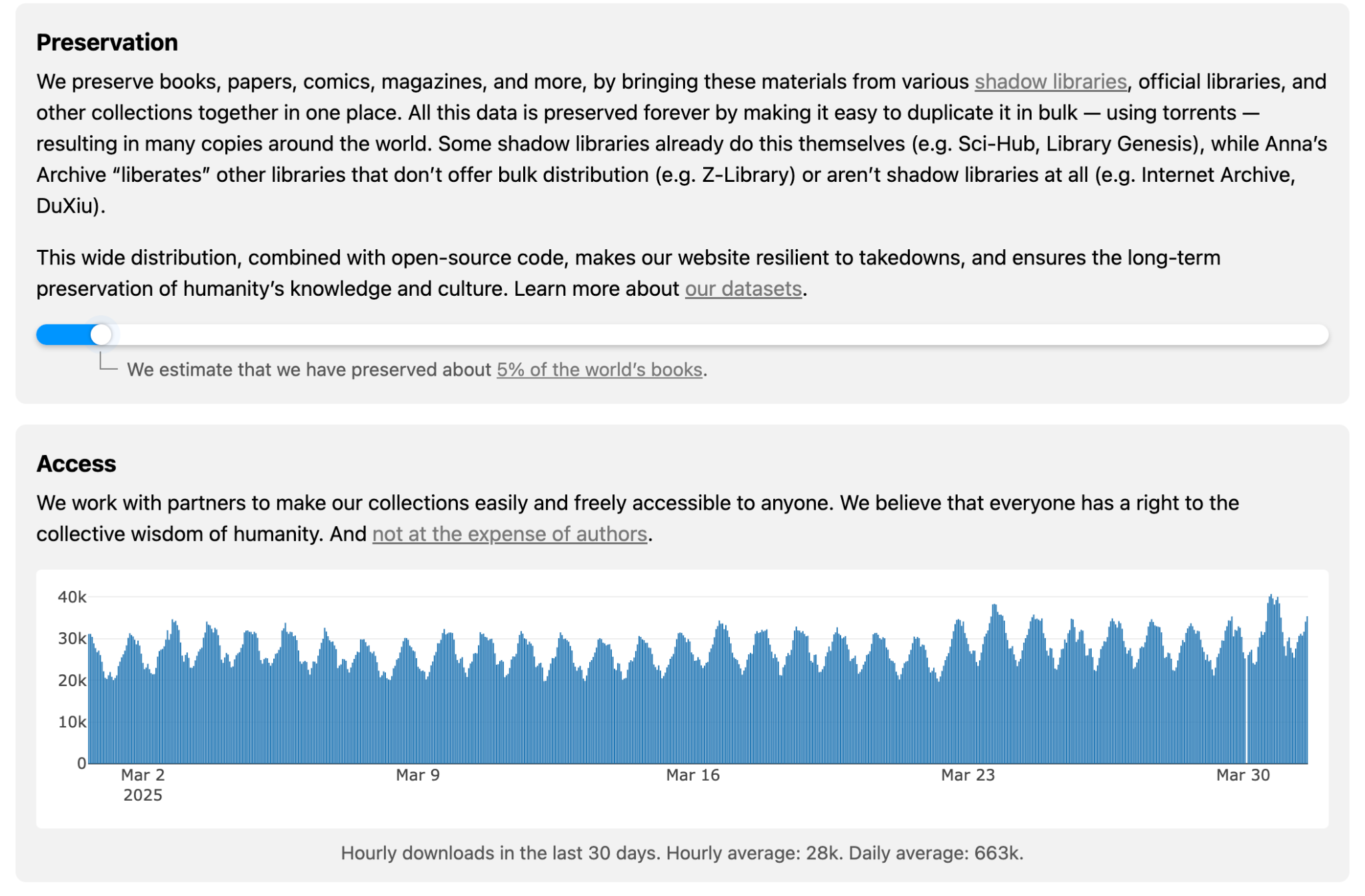

Archivists by name, librarians by self-definition, volunteers by activity, non-conformists by statements, pirates by necessity – Anna’s team presents their project as “the largest truly open library in human history”. Anna’s library (or archive?), at the current date counts over 650,000 books downloaded every day. Taking a rough circulation estimate of the largest public library in the world, the New York Public Library, that is around 30,000 copies per day, we notice that accounts for only 10% of Anna’s distribution. At the time of the publication of this issue, Anna’s Archive collected more than 40 million books and around 100 million scientific papers. This should be enough significant data to deserve an investigation on her role in the worldwide panorama of book circulation and copyright. It may be easy to dismiss Anna as petty piracy, a “little trick” that condescendent professors whisper to their students, but in fact it is impossible to consider Anna as a simple bend among many in our life of rules. Anna undoubtedly deserves better treatment and recognition. Anna’s Archive is an attempt to become a new type of library, a library that participates in the dialogue about knowledge and that tries to change the rules of its circulation.

Anna’s library: Utopian project or ordinary piracy?

We can approach the phenomenon of Anna from two sides: through the description of her tasks and from the history of the so-called "shadow libraries". As for the first one, Anna articulates very clearly the essence of her activity: the team states that it is a non-profit project with two goals:

1) preservation – backing up all knowledge and culture of humanity;

2) access – making this knowledge and culture available to anyone in the world (https://annas-archive.org/faq).

As stated, Anna’s ultimate goal is not just to found a public library, but to create a digital copy of existing books online (ideally all books) to prevent them from disappearing. A tracker keeps us updated in real time on how many books have already been copied. This material comes mostly from online repositories, official and unofficial, that Anna calls “shadow libraries”. In this sense, Anna’s Archive is in many ways the latest case of a long history of online libraries.

The term ‘shadow library’ has a double and contradictory definition. The first one is that of large databases of written texts that are stored in non-open access, such as, for example, the library of JStor. ‘Shadow’, in this sense, means that the user can know about its existence, because texts can be found, for example, with a search tool, but, as in a shadow, the content is concealed. The second and most used definition of shadow library is that of a large digital archive that collects and distributes written material (academic papers, books), and sometimes other media, violating copyright laws of some countries. In this case, the term ‘shadow’ means ‘illegal’; with the same meaning, is used the term ‘Black Open Access’ (Black OA). Following the first definition, perhaps the largest shadow library in the Internet is Google Books, which originated from a 2004 massive book digitization project involving five prominent academic libraries in the United States. In the first four years, it was intended to be a universal digital library, but by 2008, copyright issues blocked access, which is now subject to subscription, even for the libraries that provided the books.

Another important project to mention in this context is Internet Archive, the forecomer of many modern shadow libraries, although Anna directly indicates that she does not associate it with this term. Initially founded in 1996 as a means to provide “Universal Access to All Knowledge”, Internet Archive started from the assumption that a wide array of pages were written and produced through the web, that nobody cared to preserve. That produced the Wayback Machine, a powerful tool still available online that records all the web pages of the past. Slowly, the archive started collecting books and other multimedia content, and became more and a library of a new kind: most of the material was not available for downloading but users could read it online. Thanks to a special borrowing system, Internet Archive offered access to many books (according to official sources, at the beginning of 2022 it had more than 35 million books), while theoretically respecting copyright laws. Internet Archive aspires to be a legitimate online library. Nevertheless, in 2020, Internet Archive was sued by four giants of the publishing industry in the English language (Hachette, Penguin, HarperCollins, John Wiley), reducing greatly the accessibility of its content. This case makes clear how controversial the concept of lending is within the regime of current copyright law. While in a physical library a user is allowed to borrow any book, in a digital library it is forbidden, if electronic copies are on sale. This outcome suggests that what matters is not a clear definition of accessibility and use of content, but whether or not it affects the revenue of publishing companies. Internet Archive, which has the ambition to be an innovative cultural institution, is struggling to find a recognised status within this heavily biased framework, constantly kept in check by shifting copyright regulations.

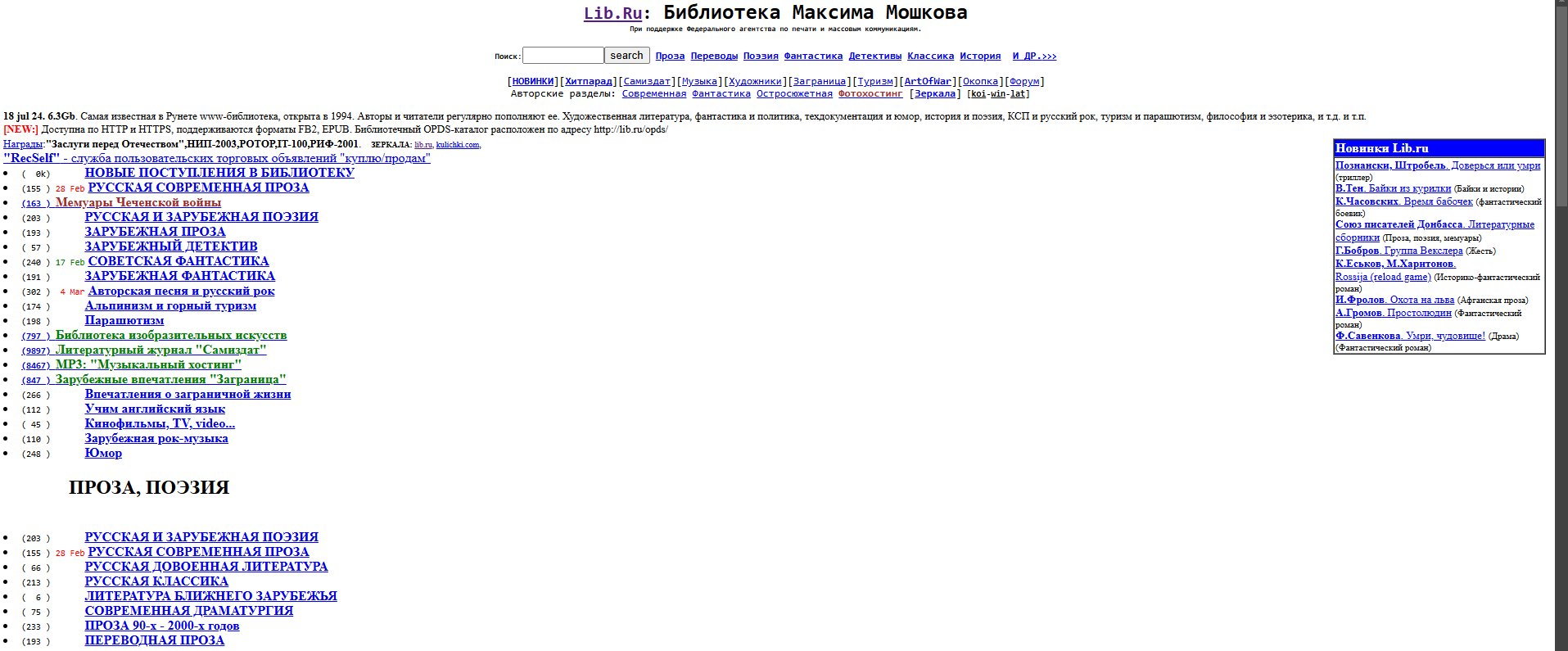

Parallel to these huge enterprises, that come from the Silicon Valley culture, exists a non less relevant history of post-Soviet online libraries. In one of the best researches published on the topic of shadow libraries, Shadow Libraries: Access to Knowledge in Global Higher Education, Balázs Bodó reconstructs the history of the creation of such shared archives within the Soviet culture and counterculture. Bodó suggests that Russian pirate libraries emerged from these enmeshed contexts:

...Communist ideologies of the reading nation and mass education; the censorship of texts; the abused library system; economic hardships and dysfunctional markets; and, most importantly, the informal practices that ensured the survival of scholarship and literary traditions under hostile political and economic conditions (Bodó 2018, 33).

Since the very beginning, Soviet copyright was very different from western: the issue of securing revenue for private individuals was nonexistent, all publishers, film studios, etc. were state-owned, that meant that most of the books and movies where openly accessible or available at a very cheap price, as they do even now. Secondly, the great laboratory of Soviet counter culture developed a series of practices to distribute censored material, from self-publication (samizdat), to the sharing of libraries and DIY means of copy and distribution. The age of Internet saw a continuation of these practices, and the first shared online archives started be set online by Russian-speaking scientist and users, who collectively digitized books by hand, downloaded the archives of the research institutions where they worked, scoured the internet to format and organise libraries that would reach tens of thousands of titles: Lib.ru (1994) by Maxim Moshkov, Kolkhoz (2002), Monoscop, Gigapedia (2000s). Each of the libraries was to some degree related to each other. Then it was the time for the widespread Library.ru (2010), that was sued in 2012 and shut down, and Library Genesis (2007), that collected the dataset of Library.ru. That is, it can be said that the Soviet counter-culture, and post-Soviet scarcity of well-stocked official distributors influenced the development of what would later become pirate libraries, exploring and developing the paths of collection, organisation, and wide dissemination of knowledge, taking advantage of the loose copyright enforcement in the early years of the World Wide Web.

Anna is in many ways a continuation of a series of many shadow libraries, and she openly declares that she was inspired by Library Genesis. On the other hand, she goes up a notch in the ambition of her goals. LibGen is not intended to contain everything, but its boundaries are created in dialogue with the community, measured by the act of actively digitizing and sharing books, and keeping a low profile (Bodó 2018, 36). Anna’s Archive wants instead to create a universal library that possibly includes and preserves all the books of the world, and it does it boldly. In other words, Anna proposes a project that has no equal in scale and ambition. In this context, Anna is perhaps the one of the few online libraries, regardless of their legal status, pursuing such goals, which, in addition, functions on a completely non-profitable basis: the work of the team is mostly volunteer and financing comes from user donations and memberships that increase download speed. Probably, Anna’s budget is much lower than any large libraries’ in the world. However, Anna’s learned from LibGen that the preservation of intellectual culture, in this case books, in the contemporary aggressive legal and online environment, implies the need to create the largest possible number of copies, so that in the event of the loss of a separate library, copies exist elsewhere. These copies of the archive are called “mirrors”. Any user can not only download single books, but create an entire copy of Anna, copying its open source code. As for today, humanities’ largest library requires one Petabyte (one million of Gigabytes) of memory, more or less the same amount of data generated in one month of shooting a Netflix series.

Today, beside Anna, there is another system that can be somehow reconnected to the post-Soviet data sharing experience, that goes through a special feature built in the messenger of Russia’s most popular social network, VKontakte. Essentially being a Russian version of Facebook, it has a reputation as one of the most reliable pirate sites, using a system of circulating private files. In other words, even a book or article sent in private messages can be found by a third-party user in the file search. Thus, the procedure for uploading data there is practically uncontrolled and does not fall on the shoulders of a small team of volunteers, like Anna’s Archive, but is a constant matter for Internet users. Moreover, all attempts to control it are hardly possible, because such data circulation is spontaneous. Sometimes the collective forces of millions of users defeat restrictions imposed by above.

The question of copyright inevitably arises. In the last decades, copyright laws strictly determined the conditions of use and access to information and creative work, with little or no regard to the goals pursued by a particular project and its financing. The meaning of the term ‘shadow library’ in this context becomes something more than just a designation of the phenomenon of piracy, but a sign of resistance to outdated copyright standards and concepts about what is a library. ‘Shadow’ for Anna is somehow homologous with the late Soviet ‘underground’. Anna is the ‘underground’ of copyright, the norms of which strive to make her cease to exist. This is clear if we read the very first post of the new-born Anna, when Anna wasn’t yet Anna, but the “Pirate Library Mirror”, in June 2022:

Introducing the Pirate Library Mirror (EDIT: moved to Anna’s Archive): Preserving 7TB of books (that are not in Libgen)

This project aims to contribute to the preservation and libration of human knowledge. We make our small and humble contribution, in the footsteps of the greats before us.

The focus of this project is illustrated by its name:

Pirate – We deliberately violate the copyright law in most countries. This allows us to do something that legal entities cannot do: making sure books are mirrored far and wide;

Library – Like most libraries, we focus primarily on written materials like books. We might expand into other types of media in the future;

Mirror – We are strictly a mirror of existing libraries. We focus on preservation, not on making books easily searchable and downloadable (access) or fostering a big community of people who contribute new books (sourcing)(https://annas-archive.org/blog/blog-introducing.html).

The Pirate Library Mirror was a very technical title, that synthesizes the foundations on which Anna was layed. At the beginning, Anna was mainly a device created in open contrast to copyright laws, considered detrimental to the more important value of preserving knowledge, hence “Pirate” by necessity. “Library”, it is simply because the focus of preservation are written materials and books. The method of this contrast is mirroring, the creation of redundant copies that make tracking of hosting services difficult and allow resiliency in case of server shutdowns, hence “Mirror”. This choice, on the other side, meant that the system must be lightweight both in terms of services, that means no tools for interacting with the data itself (search tools, etc.), and with other users (community network), features that are for example present in the Internet Archive, and that are almost considered a commodity in contemporary Internet. Nevertheless, the simplicity and rawness of Anna is what makes it unique and deserves more attention.

Anna’s rhetoric: Simple and radical

Anna’s Blog has minimal graphics, a yellow header, large Comic-Sans title, reminiscent of the first Internet blogs in the Nineties. There are just a few entries, spanning from June 2022 to today, that are actually the best source to trace the development of the project. Everything, from the graphical appearance to the writing style, tells us that Anna wants to be simple, focused on few tasks, and straightforward. Anna replaced the less appealing and anonymous Pirate Library Mirror, and tells us something about the importance of such a name:

One decision to make for each project is whether to publish it using the same identity as before, or not. If you keep using the same name, then mistakes in operational security from earlier projects could come back to bite you. But publishing under different names means that you don't build a longer lasting reputation. We chose to have strong operational security from the start so we can keep using the same identity, but we won't hesitate to publish under a different name if we mess up or if the circumstances call for it.

In some way, the name is the only thing that keeps the library unified, a holdfast. Books and files can be mirrored everywhere, but if we want to make a statement, at the end, it is necessary to fix a point, create an identity that can engage in a debate.

The necessity of a recognisable name, despite the concerns about visibility and security, is revealing of the fact that Anna wants to make a point in history of knowledge circulation. As they say, it is a “holdfast”, a “fixed point”, an “identity” that can engage a debate. The name Anna is a biblical name, the name of the queen that in 1710 invented copyright, a palindrome, but could also be the average name of an average reader, similarly to what Caroline was for the journal Queen, that gave the name to the famous offshore pirate Radio Caroline (Pedersoli, Toson 2020). The name itself induces the question “Who is Anna?”, cleverly answered: “You are Anna!”. A common name, as many common names used in marketing and branding, that wants to create complicity with the user, and, perhaps, identification. Reading the blog and seeing the development of Anna’s Archive in the last years, it is clear that, despite the initial anonymity of the project, that seemed to be just interested in technical aspects of defiance from blockage, Anna became progressively more self-conscious, developing a personality and a style that are very unique.

For example, Anna does not have an “About” page, where she states what she is, who are the founders, what are their political thoughts etc. Instead, it has a prominent FAQ page, which seems to be a literary genre in itself. It is constructed as a long interview made with the questions received by users: the first is “how can I help”. Most of the questions are explaining the technical aspects of the platform, but by reading all the FAQ page it is possible to have a quite detailed understanding of how Anna works: downloading, donations, source code. At the same time, there are quirks that make Anna’s personality emerge: “I downloaded 1984 by George Orwell, will the police come at my door?” ; “Who is Anna? You are Anna!”, and perhaps, most striking, a book list at the end:

What are your favorite books?

Here are some books that carry special significance to the world of shadow libraries and digital preservation:

Michele Boldrin, David K. Levine, Against intellectual monopoly;

Stephenson, Neal, Cryptonomicon;

Aaron Swartz, The Boy Who Could Change the World : The Writings of Aaron Swartz;

Witt, Stephen R, How Music Got Free : A Story of Obsession and Invention;

А. М. Прохоров, Физическая энциклопедия. Ааронова – Длинные Том 1.

Swartz, Boldrin, Levine, Witt are among the most important names in the Copyleft movement, and define a clear framework in which Anna is operating, and, perhaps, expressing a political view (even though Anna states in several places that she is not concerned with politics). Anna's Archive team, as in Boldrin and Levine’s book, criticizes the outdated copyright system, affirming that due to the simplification of access to knowledge in the modern world, many requirements should be modernised, such as, for example the 70 year expiration time of copyrights, much longer than patents, which spans 20 years. In other words, directly or indirectly, while refusing in its practice to deal with it, Anna is engaged in the debate over copyright law, suggesting improvements and challenging the idea that only profit from intellectual monopoly can produce quality. Open source projects such as Wikipedia or Linux, or Anna herself should be a sufficient demonstration that it is possible even the opposite.

Beside the discussion over copyright, Anna radicality arises from the dismissal and the untrust of institutions in the higher scope of preserving knowledge and share it to the future generations:

Humanity largely entrusts corporations like academic publishers, streaming services, and social media companies with this heritage, and they have often not proven to be great stewards.

There are some institutions that do a good job archiving as much as they can, but they are bound by the law. As pirates, we are in a unique position to archive collections that they cannot touch, because of copyright enforcement or other restrictions. We can also mirror collections many times over, across the world, thereby increasing the chances of proper preservation (https://annas-archive.org/blog/blog-how-to-become-a-pirate-archivist.html).

Anna’s simplicity and focus on technical aspects of preservation oblige us to think about the real effectiveness and utility of conventional institutions.

The culture of mistrust for corporations, institutions, governments, laws, is reflective of a general crisis that, perhaps, started with the great financial collapse of 2008 and the Occupy Wall Street movements. Mistrust on financial institutions quickly led to mistrust towards anything that was to some degree related to them, that is almost everything, and academic institutions in particular, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world. The same years of Library Genesis are the ones that saw the creation of the first cryptocurrencies that were developed as a response to an unreliable financial system. The main idea, in shadow libraries as in cryptocurrencies, is to decentralize the control and distribution of currency or written information. Crucially, what makes the difference is the technology of distribution and preservation of data or currency, based on sparse networks and redundant registers, rather than centralised systems. This was the main drive that led to the development of block chain technology, devised specifically to avoid the necessity of a central institution such a bank to emit and regulate the currency. In both cases, for cryptocurrency and Anna’s Archive, there is a latent unfaith in institutions that seem to be more and more unstable. Recent war episodes and sanctions that crippled globalisation, such as the exclusion of Russian banks from the SWIFT system, demonstrated how cryptocurrency could be effective in avoiding state-imposed limitations, guaranteeing anonymity, and allowing hundreds of thousands of refugees to move to foreign countries. Anna uses mostly cryptocurrencies in its transactions. Systemic anonymity and peer-to-peer/blockchain technology seem to be the tools to counteract growing global authoritarianism.

Beyond the simplicity of Anna, there is a highly challenging and technically advanced system of storing in different servers and making accessible through different pathways the library. But a simple approach may also be the answer to the need to communicate in a completely global and cross-cultural way, dealing with publications that span from Chinese scientific books to Canadian poetry. The radicality and success of Anna resides in its lightness and cleanness in the mediation between producers and consumers of knowledge. From this point of view, it may seem almost provocative and difficult to accept, as we as users of media content have been used to progressively complex graphics and services in the multimedia world. Moreover, the general approach of an evanescent curatorship is antithetical to the classical western academic and cultural world, where heavy institutions create heavy and culturally framed systems for the storage and the diffusion of knowledge.

Anna, underfunded and illegal in many countries, without a board of directors or a scientific committee, makes us question the effectiveness of such institutions in the modern world. How is it possible that Anna is capable of giving access to real knowledge to far more people and in a far more equal and efficient way than anyone else? Its existence makes us suspect that the superstructures of such institutions are not interested in developing human knowledge, but rather administer it under the influence of other powers. In the best case, they are simply not efficient enough. Anna is ultimately separating knowledge from culture, preferring the first, as she plainly states:

Per megabyte of storage, written text stores the most information out of all media. While we care about both knowledge and culture, we do care more about the former (https://annas-archive.org/blog/critical-window.html).

Anna’s speaking visualization

The radical essentiality of Anna leads naturally to the search of self-representation in a succinct way. This is not an easy task. Anna is a library that wants to collect all the world’s books, in a fashion that reminds Borges’ and Eco’s books. Umberto Eco imagined a library where every book was made of four numbers, one for the room, one for the wall, one for the shelf, and the last for the position in the shelf. These four numbers would incorporate much of the information on the library itself: for example, the second number would tell something about how many walls are there in the rooms. When we imagine to archive knowledge, mathematics and combinatory seem to be a common feature. Anna is not an exception in this game.

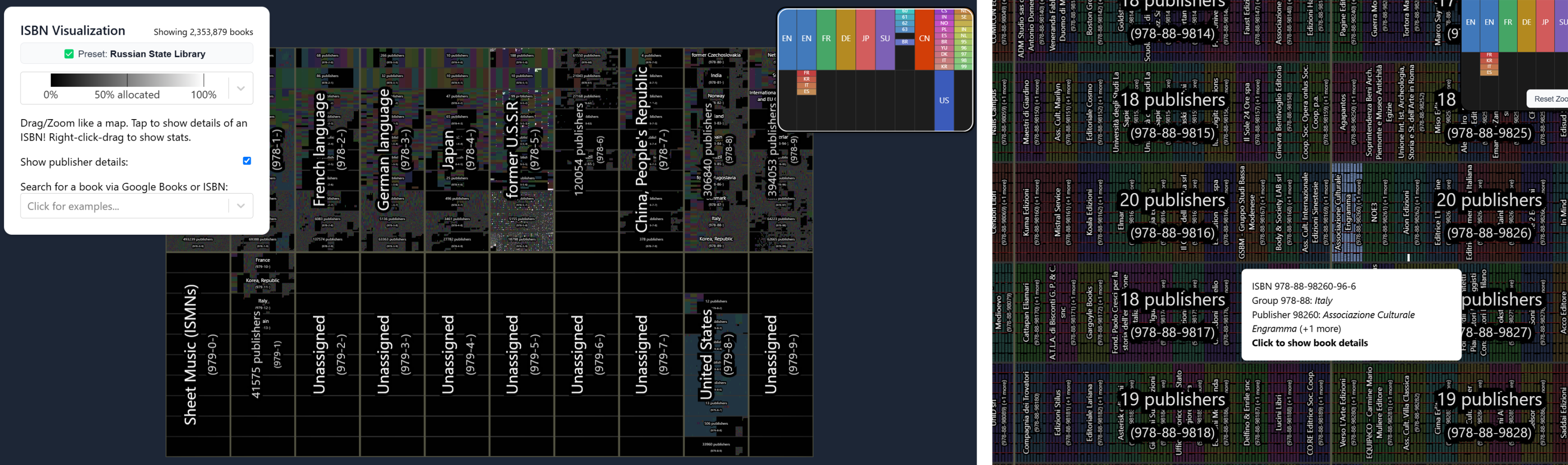

Recently, on Anna’s blog, there has been a prize competition for who could have represented in the best and more elegant way all the published books, as they call it, a “To-Do-List of Human Knowledge”. As Eco, the main character of this representation is a number, but composed by 13 digits: the common ISBN (International Standard Book Number), introduced in 1970, defines the single book edition. As Eco ’s numbers, ISBNs are divided in parts, the first one, 978, that means “this is a ISBN”, and the following, that define the group (a country or a language area), the publisher, the book. It is a comfortable system for the management of the logistics of the book intended as a product, in the same way other barcodes define tomato sauce or toilet paper at the supermarket. ISBNs are simply numbers with a prefix, and they cover a maximum of 2 billion books. It is a huge number, many times larger than all the published books until today, and a graphic representation of all the ISBNs is the first step for a general visualisation of the written human knowledge.

When describing the tasks of the competition, Anna published the simplest visualisation: a large square where each pixel represents every possible ISBN, in progressive order. Black pixels are numbers that are not yet assigned – white – published books. The image is already by itself quite revealing: we see a cryptic scheme with thousands of thin segments of different lengths, from the complete width of the square to just a few pixels, covering unevenly the space. All books written by humans are just a sparse constellation in the dark space of all possible books. Lines and segments remind of some complex combinatorial problem involving sets and subsets of a larger set, but are actually the product of human administration, a combination of regularity and randomness at different scales. Numbers are assigned in large chunks, such as 100 million, to different countries, that then decide how to distribute them. Hence, we can see the constellation breaking at more or less regular intervals, and then the intervals themselves divided in different ways, sometimes regularly, sometimes not, sometimes at a larger scale, sometimes at a smaller, in fractal structures. In this image humanity’s library is not a plain row of books, filling shelf after shelf as we could see in a physical library, or in the imagined ones by Eco and Borges, but rather a messy and mostly void space whose emptiness is merely disturbed by the presence of books.

The main problem of this representation is that it fills the space in lines, and single clusters of books, such as, for example, all Brazilian literature, are thinned in a horizontal segment just one pixel high.

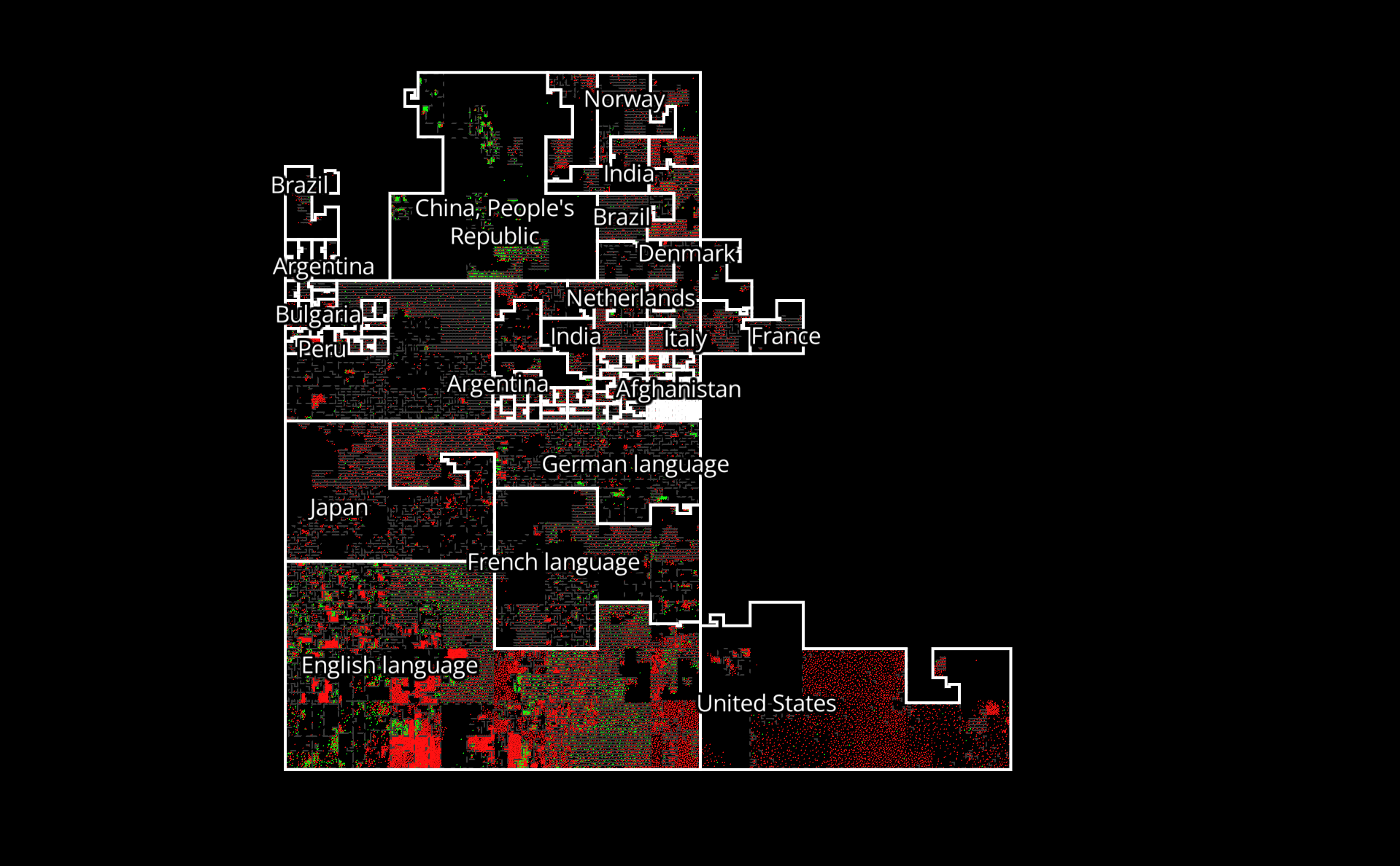

To overcome this, one of the winning competition entries tries to lay the ISBN number line in a way that numbers close together can form an area or a patch in two dimensions. To achieve this, it is used a space-filling curve, a special mathematical device that comes from Peano’s paths of space tessellation, that were developed to deal with the problem of measurability of infinity.

The line snakes around the plane outlining different groups in patches that are similar to a geographical map, with winding fractal contours as in an ideal coastline. Each coloured pixel inside the shapes represents a published book. Different countries, of progressively smaller size, are nested one in each other, and may continue indefinitely, as far as there is space available. Shapes are complex and unique, and give us a visual idea of the quantity of books published in each language. English is by far the largest. The previous sparse constellation has condensed in a unique geography of human knowledge, not based on traditional categorisation (such as the Dewey classification in classic libraries), but according to an arbitrary set of rules and mathematical visualisation of them. As in the previous image, the continents of books are more similar to archipelagos immersed in a dark sea, but we can start comparing them and see, as in a giant Risiko map, which continents are more powerful in the production of books. Unsurprisingly, they are little different from their geopolitical counterparts.

The second representation, that won the prize, is, on the opposite, much more orderly, more similar to Borgesian and Ecoian imaginary libraries, with books arranged in regular virtual shelves, arranged in regular cases, arranged in regular clusters, and so on, in a progression of larger and larger subsets and sets. In this case, the groups are not creating different interlocking shapes, but are all a one-size row of rectangles, with different levels of infill. The previous fractal geography of human knowledge has been substituted by a cold hearted, but more reassuring table, tidy enough to find all what we are looking for, but also disturbing in the rigidity of the grid, similar to an infinite Hippodamian city where the allotments are slowly but inexorably getting exploited until the last one will be taken.

These are just the first attempts at what seems to be an overly complex exercise of data visualisation, but Anna’s Archive is one of the few libraries that is trying to do it. These exercises in representing an understated “To-Do-List” are actually arising the fundamental question of what is today a library or an archive. Representing all humanities’ books it makes human knowledge in a sense overseeable, accessible, controllable, at first glance. But then, getting into the details of these representations, we are overwhelmed by the density of their inner structure, its intricate and irregular recursivity.

As libraries become larger, the method of their representation, the structure of their archive, becomes the library itself. It is the combinatorics of its elements that makes it understandable and navigable, as in Eco’s and Borges’ visions. And perhaps Anna is more bizarre and complex than they would have ever imagined for a universal library. And yet, being an utopian library for the future, she makes their dreams come true.

Anna and Artificial Intelligence

Since the universal library in its representation and consistency seems infinite and overwhelming for a human mind, it is nevertheless limited in number, meaning that can be scanned and manipulated with the help of large language models (LLMs). Anna realised quite early that its archive would have been an extremely precious resource for the training of LLMs:

This is a short blog post. We’re looking for some company or institution to help us with OCR and text extraction for a massive collection we acquired, in exchange for exclusive early access. After the embargo period, we will of course release the entire collection.

High-quality academic text is extremely useful for training of LLMs. While our collection is Chinese, this should be even useful for training English LLMs: models seem encode concepts and knowledge regardless of the source language (https://annas-archive.org/blog/duxiu-exclusive.html).

Nowadays Artificial intelligence has become a strategic asset, used for data analysis, security, and military applications. We are assisting at an arms race in this field, and Language Models are particularly useful in the extraction of information from archives. In a not distant future, any user will be able to ask the AI to retrieve, sort and summarise all the relevant information on a specific topic, looking it up in the entire world’s library. It would be far more reliable and precise than models trained to search online. And the more the model is trained to read the texts printed from the 1400’s on, the better will get at it, being able to independently collect information and answer questions.

Current copyright rules are not only unfit for this new scenario, but even possibly dangerous, as Anna states:

Me and my team are ideologues. We believe that preserving and hosting these files is morally right. Libraries around the world are seeing funding cuts, and we can’t trust humanity’s heritage to corporations either.

Then came AI. Virtually all major companies building LLMs contacted us to train on our data. Most (but not all!) US-based companies reconsidered once they realized the illegal nature of our work. By contrast, Chinese firms have enthusiastically embraced our collection, apparently untroubled by its legality. This is notable given China’s role as a signatory to nearly all major international copyright treaties (https://annas-archive.org/blog/ai-copyright.html).

The history of shadow libraries will change soon because of Large Language Models. One of the main difficulties in training artificial intelligences is having good databases with reliable information. This is exactly what shadow libraries are, huge, well-ordered collections of reliable material. If some corporations can have free access to the precious archive, while others are bound by copyright law, the former would have an enormous advantage, as they can train their programs with books written by specialists, while the latter must make use of limited archives or unreliable and nonhomogeneous sources from the web and social networks. And this is what is apparently happening with Chinese companies training their artificial intelligences with Anna’s Archive. And it may also mark the end of open libraries and Open Access in general. Countries and corporations might in future avoid publishing in an accessible way in order to reduce competitor’s advantage. The Universal Library could become in the future the Universal Machine Library, and shadow libraries may avoid granting complete access to limit exploitation by artificial intelligences.

Conclusion

While at the beginning of the 20th century the question was about the state of a work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, now, in the 21st century, we are facing a reaction to this – with the cessation of reproducibility. A similar process is happening with the dissemination of knowledge. While earlier there were processes for the introduction of mass literacy and education, now we are seeing a certain course to suspend the distribution of knowledge: under the pretext of security issues or the rights of an individual author. From Anna’s perspective, we can talk about a certain intellectual reactionism, about a course towards the elitisation of knowledge, which is becoming more and more distinct. What does this symptom indicate? The trends in the development of science of the future which will become more noticeable later? The fact that mass science is no longer needed for some reason? But what then does a library become? What is the role of Anna in this context?

Against this background, Anna’s Archive should be helpless. Instead: radically simple, incredibly intricate in its functioning, mirrored in thousands of copies, ungraspable, openly anticultural and anti-academic, she reacts to these processes, trying to initiate the dialogue about the copyright system which is hardly possible because of her outspoken “shadowness”. However, the reaction to new processes of global authoritarianism is not much in her words and in blocked blogs, rather resides in the project itself. Anna is a large protest against what is happening. Anna is a real underground of knowledge, an utopia that resists the threat of contemporary dystopias. But even in the construction of a utopian ideal library of the future, old questions inevitably arise: even if you copy, where to start? What is more important? Books? Articles? Novels? Scientific works? Works on natural philosophy or ancient literature? Even a new type of library cannot avoid the old problem of the hierarchy of genres, even if it is represented only through ISBN codes. Anna, in its simple radicality, tries to deal in the most rational way possible, inventing new ways of overseeing, that is representing, all humanities’ books. It is the project that until now got closer to both the creation and the representation of a truly universal library - not the speculation of a writer, nor a fancy cultural endeavour - a highly technical preservation and distribution system that is suitable to work seamlessly across global cultures.

Perhaps Anna is not a cultural phenomenon, but really just a pirate site - another secret tool of academics and students. Either way, even if she is just a torrent site, are all these blockings really necessary? Is it really necessary to subject knowledge databases, mostly created with research publicly funded, to sanctions? Will there be an effect? And will there be an unexpected effect? As academics, we will selfishly hope that Anna will live for some time in this struggle for the right to free knowledge and reach the mark of at least 10% of all downloaded books. And then, perhaps, we will be able to get a little closer to the answer to the questions: What is Anna? Who is Anna?

Maybe the best hint comes again from Anna’s peculiar FAQ bibliography, by the last, and curiously odd book, an old Soviet physics enciclopedia (Prohorov 1988) that starts alphabetically with the the Aharonov-Bohm effect, that has the same name of AAron Schwarz:

Quantum mechanic effect, characterised by the influence of an external electromagnetic field, concentrated in a region that is not accessible, on the quantum state of a charged particle (Prohorov 1988, 7).

A foundational effect of modern qunatum phisics that states that there can be situations in which particles are affected by a field even if the field is closed, due to a invisible coupling between wave funcion a electromagnetic potential - as Aaron Schwarz’s activism, that even when confined and repressed, is able to cause effects at distance, in charged particles/free minds that go beyond the commonly accepted principles of locality, and that can act globally, determining a “phase shift”: the Anna’s effect.

Bibliographical References

- Adams 2025

C. Adams, Vanishing Culture: When Preservation Meets Social Media, Internet Archive Blogs, 9 April 2025. - Aiguo (2009).

L. Aiguo, Digitizing Chinese Books: A Case Study of the SuperStar DuXiu Scholar Search Engine, “Journal of Academic Librarianship”, 2009, 35, 277-281. - Anna 2022-2025 I

Anna’s Blog. - Anna 2022-2025 II

Anna’s Archive blog on Reddit. - Bodó 2018

B. Bodó, The Genesis of Library Genesis: The Birth of a Global Scholarly Shadow Library, in Karaganis et al. 2018, 25-51. - Boldrin 2008

M. Boldrin, D. K. Levine, Against Intellectual Monopoly, Cambridge, 2008. - Correa, Laverde-Rojas, Tejada, et al. 2022

J.C. Correa, H. Laverde-Rojas, J. Tejada, et al., The Sci-Hub effect on papers’ citations, “Scientometrics” 2022, 127, 99–126. - Karaganis et al. 2018

J. Karaganis (ed.), Shadow Libraries: Access to Knowledge in Global Higher Education, Boston 2018. - Pedersoli, Toson 2020

A. Pedersoli, C. Toson, Onde libere e rock ‘n’ roll. La rivoluzione delle emittenti offshore, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 174, luglio/agosto 2020, 25-76. - Prohorov 1988

A.M. Prohorov, Fizicheskaya entsiklopediya. AAronova – Dlinnye tom 1, Moscow 1988. - Ruhenstroth 2014

M. Ruhenstroth, Schattenbibliotheken: Piraterie oder Notwendigkeit?, interview at Balázs Bodó, iRights info, 10 October 2014. - Rumfitt 2022

A. Rumfitt, In defence of Z-Library and book piracy, dazeddigital.com, November 2022. - Slum 2025

SLUM: The Shadow Library Uptime Monitor. - Stephenson 1999

N. Stephenson, Cryptonomicon, New York, 1999. - Swartz 2015,

Aaron Swartz, The Boy Who Could Change the World: The Writings of Aaron Swartz, New York, 2015. - Van der Sar 2025 I

E. Van der Sar, Pirate Libraries Are Forbidden Fruit for AI Companies. But at What Cost?, torrentfreak.com, 31 January 2025. - Van der Sar 2025 II

E. Van der Sar, Anna’s Archive Urges AI Copyright Overhaul to Protect National Security, torrentfreak.com, 1 February 2025. - Wikipedia 2025

Wikipedia page for Shadow library, accessed April 2025. - Witt 2015

S. R. Witt, How Music Got Free: A Story of Obsession and Invention, New York, 2015.

Abstract

This paper attempts to read Anna’ Archive in the context of the so called “Shadow Libraries”, and its effects on the global circulation of knowledge and the debate over copiright. Anna is the last of a long series of online repositories of shared written material that originated in the early years of the World Wide Web, especially in post-Soviet academic environments. Anna has a unique approach to digital preservation, based on a radical refusal of any law or insitution that limits the possibility of access and conservation of knowledge, encouraging the act of copying or mirroring her data. Anna’s style has developed from the beginning of the project, and has slowly developed a personality and a sophisticated work procedure. At the same time, Anna seems to seek a simple and radical approach, in order to act at a truly global scale. Anna is perhaps the only libary in the world that aspires to be universal, and is attempting to catalog and visualise the entire humanity’s written collection in innovative ways, that remind of the fictional libraries immagined by Borges and Eco, and questions us on what should be the real nature of a library in the future.

keywords | Anna’s Archive; universal library; shadow library; Intellectual property; Knowledge representation; AI training datasets.

la revisione di questo contributo è stata affidata al comitato editoriale e all’international advisory board della rivista

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Elizaveta Kozina, Christian Toson, Anna, the Universal Library, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 222, marzo 2025.