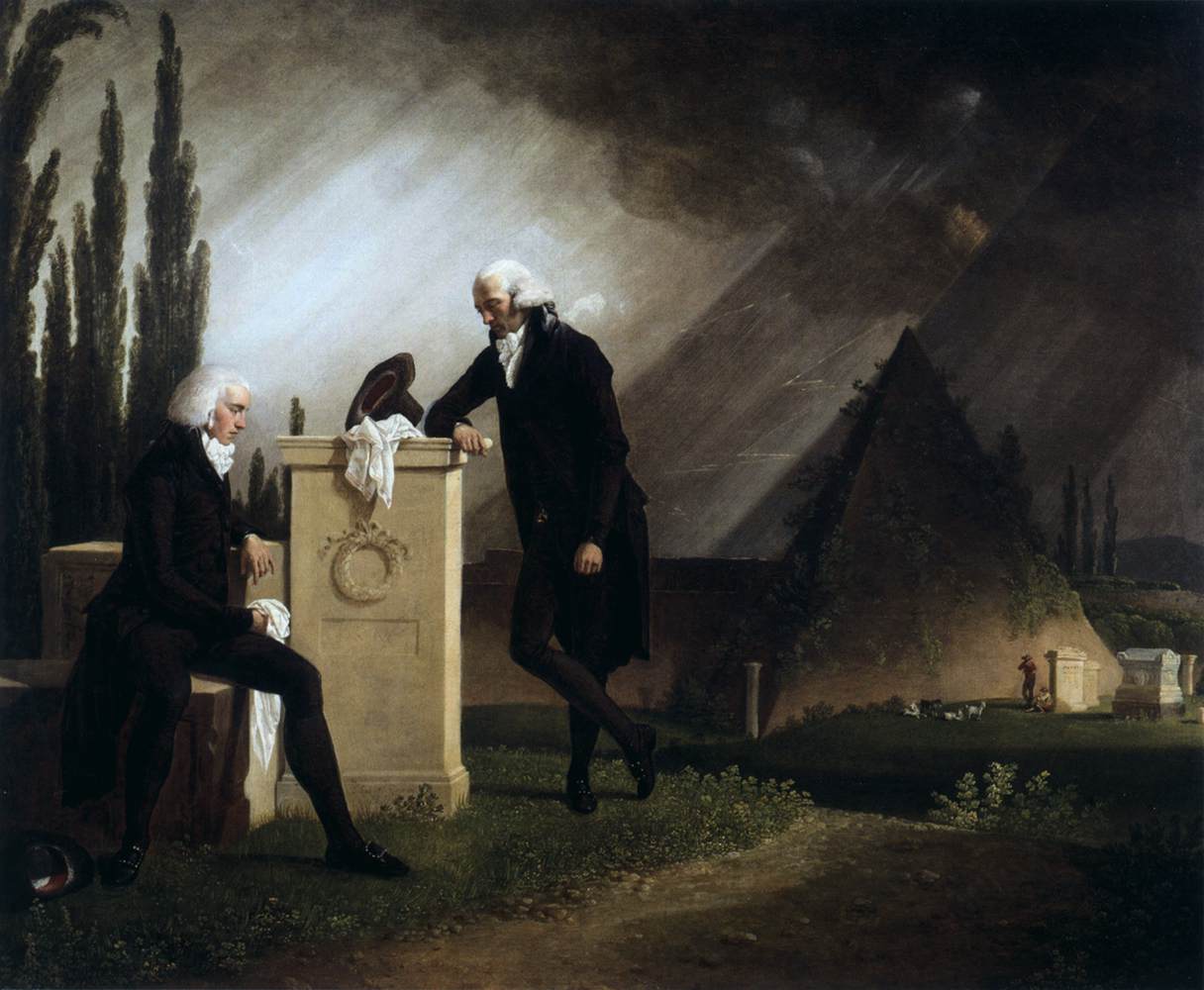

1 | Jacques-Henri Sablet, Élégie romaine, oil on canvas, 1791, Brest, Musée des Beaux-Arts.

For travel writers on the Grand Tour, the campagna romana offered a geographical space for reflection and inspiration. Anna Jameson devotes a great deal of attention towards this area in her first publication Diary of an Ennuyée (1826), henceforth referred to simply as Diary, a semi-autobiographical travel diary with a fictional gothic subplot (Punzi 2001). This paper explores Jameson’s representation of the Roman countryside, and, given her later career as an art critic (Clara 1967; Johnston 1997), offers some comparisons to artwork that visually complement the themes touched upon in the Diary, with particular attention towards the rovinismo movement and its philosophical implications from a Romantic perspective (McCue 2014). For Jameson, the sites of ruins are a locus for reflection, wonder, and awe, as she notes at the Pyramid of Gaius Cestius:

This part of old Rome is beautiful beyond description, and has a wild, desolate, and poetical grandeur, which affects the imagination like a dream—The very air disposes one to reverie. I am not surprised that Poussin, Claude, and Salvator Rosa made this part of Rome a favourite haunt, and studied here their finest effects of colour, and their grandest combinations of landscape. I saw a young artist seated on a pile of ruins with his sketch book open on his knee, and his pencil in his hand—during the whole time we were there he never changed his attitude, nor put his pencil to the paper, but remained leaning on his elbow, like one lost in ecstasy (Jameson 1826, 71).

Visually, the artist mimics his own still subjects in a sort of ironical reversal of roles that is typical of Jameson’s witty style. Meanwhile, the writer herself conjures up an almost unreal, dreamlike image, with the artist somewhat suspended in time as an individual amongst the splendour of the ruins, themselves a symbol of a greater whole, all picturesquely contained within an episode of Romantic rapture and reflection. All the while, Jameson steadily narrates the scene, remaining an anonymous figure the artist is unaware of, while the latter has himself just become a subject in Jameson’s vivid depiction of the scene, producing a metaphor that yet again cleverly plays on the very act of contemplation of the individual and the whole.

This fascination with ruins is certainly not something unique to Jameson, but rather finds its roots in a wider contemporary interest in the rovinismo movement, which proved particularly germane in relation to depictions of the landscape of the campagna romana in both art and literature. In the previous quotation, Jameson tellingly lists several artists (to whom we may add Corot, Panini, and Ricci) who often produced landscape art featuring views heavily populated by obelisks, tombs, sarcophagi, and other similar pieces of architecture, nearly always in a capriccio style. In such depictions we can find several interwoven themes that prompted travellers to eulogise their surroundings. First, there was the sublime vision created by the combination of architecture and nature, of manufactured objects coupled with organic mass. Second, the idea of the ruin-strewn Roman countryside functioned as a memento mori, a reminder of the inevitable passing of time, the cyclical nature of history, and the mortality of the viewer. Third, and closely following the philosophy of the second, was the concept of Roman ruins posing as a distinctly historical vanitas, encouraging the viewer to recall the decadence of the Roman Empire and its subsequent fall, all seen through the lens of Britain’s imperial power at the time.

Within the context of Romanticism, ruins prompted the idea that the viewer should be aware of their own mortality, and should feel the both awe and terror in the face of the sublime works of past civilisations. The ruins surrounding Rome were thus seen as physical reminders of time's relentless wings beating on through the ages, sparing no person or people, whatever their status or greatness. That the now-absent and once-great historical figures of Ancient Rome are from the same stock as the Italian peasants now occupying the same scenes suggests a pathetic substitution of staffage. Once magnificent palaces, which flourished so proudly centuries ago, now decay before the traveller's eyes, and are no longer bustling with the activity of the industrious Romans, but instead feature as protagonists farmers, shepherds, and other rustic characters (Brettell 1986). In fact, the Roman countryside can seem sometimes to be populated solely by such rustic figures, adding to the desolate but pastoral portrayal Jameson gives us:

All this part of Rome is a scene of magnificent desolation, and of melancholy yet sublime interest: its wildness, its vastness, its waste and solitary openness, add to its effect upon the imagination. The only human beings I beheld in the compass of at least two miles, were a few herdsmen driving their cattle through the gate of San Giovanni, and two or three strangers who were sauntering about with their note books and portfolios, apparently enthusiasts like myself, lost in the memory of the past and the contemplation of the present (Jameson 1826, 203).

As in the first quotation, aside from the herdsmen, Jameson again notes only fellow travellers, which enforces the idea of the area being a place under a distinctly foreign gaze. In fact, rather than Italian peasants being observed and scrutinised, Luzzi (2002) posits several examples of when they are completely ignored or marginalised, very often in favour of foreign travellers. A good instance of such a phenomenon would be Jacques Sablet’s Élégie romaine [Fig. 1], a depiction of the Protestant cemetery in Rome that again features the Pyramid of Gaius Cestius cited previously by Jameson. In Sablet’s painting, the singular Italian peasant with his flock of sheep is relegated to the obscure foreground, afforded little overall detail, while the two foreign gentlemen dominate the piece in their contemplation.

2 | Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Site d'Italie, Soleil Levant, oil on canvas, ca. 1835, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum.

These tropes of decay, lifelessness, and general passivity, are used to metaphorically frame Rome’s position in the eyes of the foreign, particularly British traveller. The notion of life constantly passing us by, of time's destruction of humanity’s creations, and ultimately humans themselves, is coupled antithetically with the still-living inhabitants of Italy, who seem oddly frozen in time, as if suspended for the viewing purposes of gazing tourists. In this landscape, Jameson even imagines tombs where perhaps there are none, conflating the homes of the living with the graves of the dead:

No—not the grandest monuments of Rome—not the Coliseum itself, in all its decaying magnificence, ever inspired me with such profound emotions as did those nameless, shapeless vestiges of the dwellings of man, starting up like memorial tombs in the midst of this savage but luxuriant wilderness (Jameson 1826, 219).

In an obliteration of the present, lost in the inescapable rumination of the past, for Grand Tourists such as Jameson, Rome symbolises the ceaseless passage of time: its ruins are a spectacle of the cyclical manner of the ages and an invite to the viewer to reflect on their individual existence measured within the larger, collective whole of civilisation. Jameson touches upon another philosophical consideration regarding the past and how we interpret what those before us have left behind, recounting:

I trod to-day over the shapeless masses of building, extending in every direction as far as the eye could reach. Who had inhabited the edifices I trampled under my feet? What hearts had burned—what heads had thought—what spirits had kindled there, where nothing was seen but a wilderness and waste, and heaps of ruins? (Jameson 1826, 78).

The notion that Jameson alludes to here is the Latin term Ubi sunt, a shortened form of a longer phrase Ubi sunt qui ante nos fuerunt?, essentially meaning “Where are those who were before us?”. While sometimes employed in a nostalgic sense, the motif is perhaps better understood here as a meditation on mortality and life's transience. While it is a common cliché to speak about contemporary travellers to be literally walking over history, this phrase is perhaps truest in the city of Rome, with its countless hidden sites and objects that may still remained uncovered to this day. The Romantic predilection for ruins is based upon their tangible, conscious weight of past existence now barely traceable in the outlines of a ‘modern’ city, emerging from, or perhaps rather being consumed by, the organic elements of nature itself. Time standing mightily as the only insurmountable force, its relentless pressure placed upon not only the works of humans, but on the mortality of humans themselves, is central to the Romantic fascination of what ruins imbue metaphorically.

As has been clearly noted so far, tombs or graves feature as visually emphasised sites placed amongst otherwise generic ruins. Such sites are consistently employed to elucidate the memento mori trope, while the portrayal of the Roman countryside itself is generally steeped in pastoral, Arcadian imagery, which at the same time can seem to suggest a surreal stillness to a sparsely populated area. Regarding the idea of pastoralism in relation to Roman ruins, Corot offers a perfect complement to Jameson’s description in Site d'Italie, Soleil Levant [Fig. 2]. This painting features ruins not in the foreground, but behind the principal focus of the piece, fading slowly into the soft morning light, and portrayed with a neutral passivity to the richer colours of the scene. The centre of the painting shows a small herd of cows, and to their right, a group of herders, seemingly in revel, dancing, lying on the grass, and sitting in the shade of the overhanging trees. Here Corot taps into the Romantic sentiment towards the rural but pure figures, jocundly playing, and set against the melancholic backdrop of the pale, crumbling ruins.

3 | Salvator Rosa, Ruins in a Rocky Landscape, oil on canvas, ca. 1640, Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art.

In contrast to the soft, pastoral representations of ruins, Salvator Rosa instead represented a tempestuous envisioning of the sublime in Italian landscape art, seen in his gloomy renditions of views such as Ruins in a Rocky Landscape [Fig. 3]. Despite Rosa's status as a Baroque painter, his landscapes were still so influential in the Romantic period that they often became indiscriminately coupled with tropes of later painting styles by British travel writers, while also blossoming within the realm of literature in the popular genre of Gothic horror. In the Diary, Jameson herself playfully alludes to the stylistic devices of writers such as Ann Radcliffe in relation to the brooding, melancholic landscapes of the Italian Peninsula, when she humorously comments:

In its present ruined state, it has a very picturesque effect; and though the presence of the banditti would no doubt have added greatly to the romance of the scene, on the present occasion we excused their absence (Jameson 1826, 54).

Here, Jameson’s playful blending of art and literature reminds us not only of her knowledge of Rosa's paintings and Radcliffe’s romance novels, but also indicates the prevalence in the Romantic imaginary of combining certain tropes to concretise a mental image of Italy in the minds of foreign travellers (Chard 1999). Jameson’s allusion to brigands and highwaymen, who featured as reminders of the dangers of travelling, finds its principal inspiration with Radcliffe, who employed such characters to reinforce the Romantic image of Italy as wild, beautiful, seductive, but with an element of underlying fear.

Bibliographical references

- Brettell 1986

C.B. Brettell, Nineteenth Century Travellers' Accounts of the Mediterranean Peasant, “Ethnohistory” 33 (1986), 159-173. - Burke [1757] 1990

E. Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful [1757], New York 1990. - Chard 1999

C. Chard, Pleasure and Guilt on the Grand Tour: Travel Writing and Imaginative Geography, 1600-1830, Manchester 1999. - Findlen, Roworth, Sama 2009

P. Findlen, W.W. Roworth, C.M. Sama (eds.), Italy's Eighteenth Century: Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour, Stanford 2009. - Fortunati, Monticelli, Ascari 2001

V. Fortunati, R. Monticelli, M. Ascari (eds.), Travel Writing and the Female Imaginary, Bologna 2001. - Gallagher 2020

H. Gallagher, Vibrant Art on the Grand Tour in Anna Jameson’s ‘Diary of an Ennuyée’, in K. Singer, A. Cross, S.L. Barnett (eds.), Material Transgressions: Beyond Romantic Bodies, Genders, Things, Liverpool 2020, 107-124. - Gilroy 1996

A. Gilroy, ‘Love's History': Anna Jameson’s Grand Tour, “The Wordsworth Circle” 27 (1996), 29-33. - Jameson 1826

A. Jameson, The Diary of an Ennuyée, London 1826. - Johnston 1997

J. Johnston, Anna Jameson: Victorian, Feminist, Woman of Letters, Aldershot 1997. - Luzzi 2002

J. Luzzi, Italy without Italians: Literary Origins of a Romantic Myth, “MLN” 117 (2002), 48-83. - Mann 2012

C.A. Mann, Pilgrims of Beauty Art and Inspiration in 19th-Century Italy, “RISD Museum” 38 (2012), 1-16. - McCue 2014

M. McCue, British Romanticism and the Reception of Italian Old Master Art, 1793-1840, Ashgate and Farnham 2014. - Mills 1991

S. Mills, Discourses of Difference: An Analysis of Women’s Travel Writing and Colonialism, London 1991. - Parshall 2011

P. Parshall, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo: The Pastiche as Capriccio, “Print Quarterly” 28 (2011), 327-330. - Punzi 2001

M.P. Punzi, Il mito di Corinne: viaggio in Italia e genio femminile in Anna Jameson, Margaret Fuller e George Eliot, Rome 2001. - Clara 1980

T. Clara, Anna Jameson: Art Historian and Critic, “Woman’s Art Journal” 1 (1980), 20-22. - Clara 1967

T. Clara, Love and Work Enough: The Life of Anna Jameson, Toronto 1967. - Wood 2001

G.D. Wood, The Shock of the Real: Romanticism and Visual Culture, 1760–1860, New York and Basingstoke 2001. - Yaegar 1989

P. Yaegar, Toward a Female Sublime, in L. Kauffman (ed.), Gender and Theory: Dialogues on Feminist Criticism, Oxford 1989, 191-212.

English abstract

For travel writers on the Grand Tour, the campagna romana offered a geographical space for reflection and inspiration. Anna Jameson devotes a great deal of attention towards this area in her first publication Diary of an Ennuyée (1826), a semi-autobiographical travel diary with a fictional gothic subplot. This paper explores Jameson’s representation of the Roman countryside, and, given her later career as an art critic, offers some comparisons to artwork that visually complement the themes touched upon in the Diary, with particular attention towards the rovinismo movement and its philosophical implications from a Romantic perspective.

keywords | Anna Jameson; Rovinismo; travel diary; Grand Tour.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: D.G. Lyons, Anna Jameson and the campagna romana, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 218, novembre 2024 | PDF