From paratoxic to paradoxes (and vice versa)

Presentation of the exhibition at Benaki Museum, Athens

Nadja Argyropoulou

English abstract

My suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.

Haldane 1927

My grandmother used to love Kojak. I’d say, “Mimi, why do you love Kojak so much?” She’d say, “He just sends me.” And it was the only time I ever had anybody, the only time I ever knew anybody to use the word in that way, that, you know, Sam Cooke uses it in a song. It’s kinda one of those terms that’s maybe even archaic when he says it. But there’s that sense of being sent, you know. And that’s what I mean – to be sent, to be transported out of yourself, it’s an ecstatic experience, it’s not an experience of interiority, it’s an experience of exteriority, it’s an exteriorization. And so we’re sent. We’re sent to one another. We are sent by one another to one another. To the point that, by the time you get to work that shit out as well as it should be worked out, we’re sent by one another to one another until one and another don’t signify anymore (Fred Moten, retrieved from Litherary Hub).

Visit the environment. Traverse circumstances floating like crowns around the instance or substance, round the axis of the act. Make use of what is cast aside. […] Do not despise conjunctions or passages. Hermes often veers off as he goes along. And detaches himself. Observe the mingled flows and the places of exchange and you will understand time better. Hermes gradually finds his language and his messages, sounds and music, landscapes and paths, knowledge and wisdom. […] He loves and knows the spot where place deviates from place and leads to the universe, where the latter deviates from the law to invaginate into singularity: circumstance (Serres [1993] 2008, 287).

Is man’s relationship to the environment the most controversial, recalcitrant and unfinished project of humanity? Can a question like this be transmitted from a country-in-crisis? Can it move us out into a new weather? Can it escape the didactic and suggest resistance as entanglement? Can such a question be shaped by and depend upon the joy of inventiveness, the justice of horrible mixtures, the possibility of critical action and rebirth?

The exhibition Paratoxic Paradoxes, curated by the undersigned and organised recently by the Benaki Museum and Polyeco Contemporary Art Initiative in Athens, Greece engaged with the trouble of this question and aligned with those thinkers, activists, scientists, artists, pedagogues, entities who have the courage to attempt a synthesis on the large scale of the cosmos. It sided with those who strive to form broad alliances, devise new, post-anthropocentric paradigms, promote economies of symbiotic actions, and fight against the toxicity of socioecological disasters, accelerating extinctions, neoliberal dictums, historic distortions, aesthetic levelling, populist ideological constructs, fear and poisonous fundamentalism.

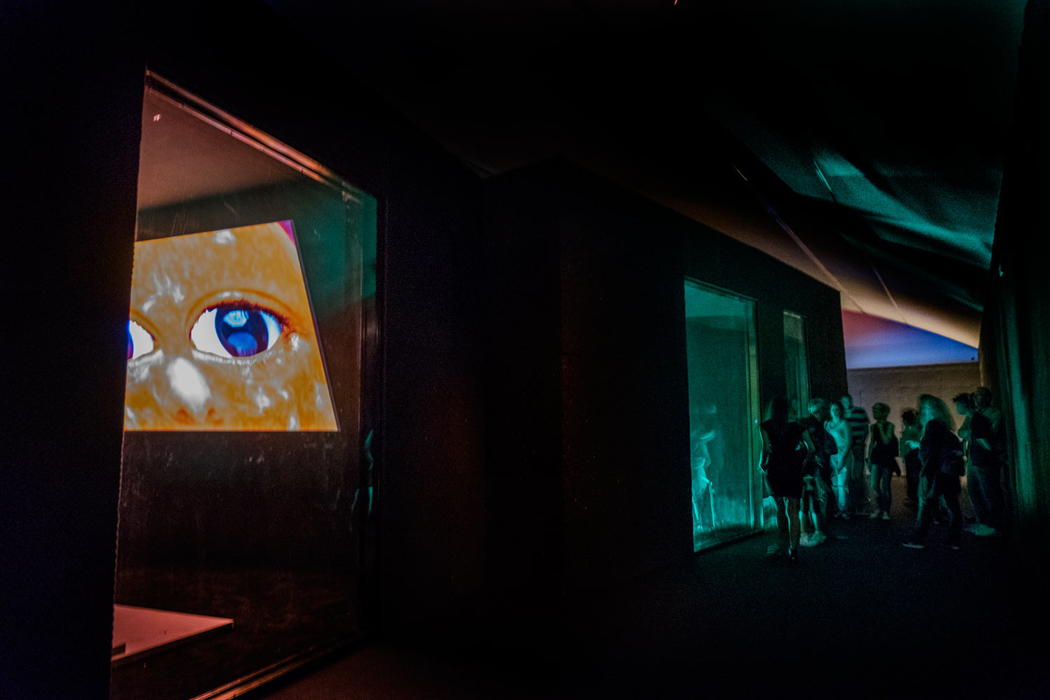

Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition, installation shots at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. Photos © Tassos Vrettos. Courtesy of the curator and Tassos Vrettos.

New works of 'moving image' (film, video, animation, digital imaging, etc.), commissioned internationally for a capsule collection and its exhibition, explored these critical issues through the contemporary viewpoint of political ecology and eco-criticism, as the latter is currently shaped at the point of intersection among arts, politics, justice and socioeconomic demands, beyond naive classifications, univocal readings, outdated strategies and exhausted lexicons.

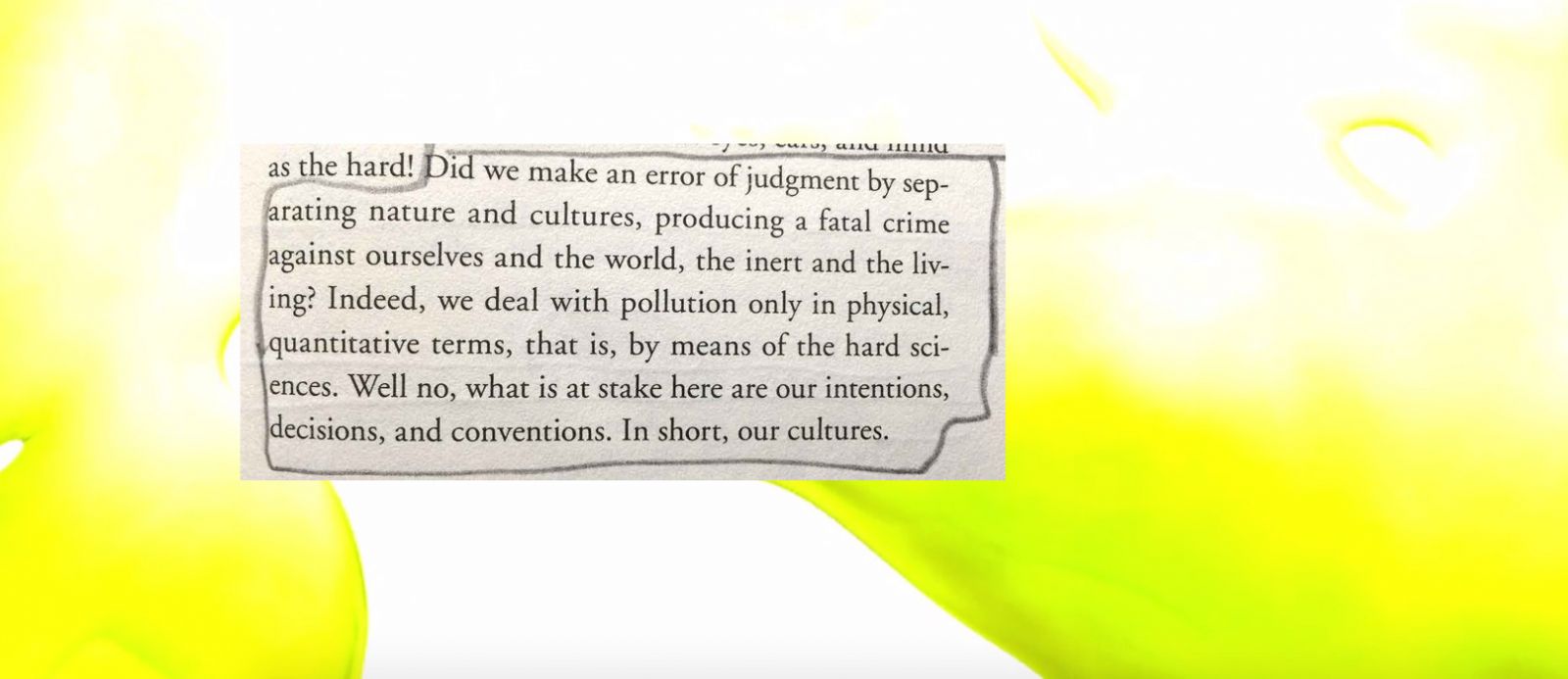

As a long history of ideas, philosophies, sciences, arts, politics and global events confirms humanity’s tumultuous relationship with the environment and recent developments expose all its pending matters in dizzying disarray and urgency and reporting on carbon data — it is worth noting that US President Donald Trump framed his recent decision to pull the USA from the landmark Paris climate agreement as “a reassertion of America’s sovereignty”; the US, the world’s second-largest emitter of carbon emissions, behind only China, has thus ceased all implementation of the Paris accord, including contributions to the UN Green Climate Fund (to help poorer countries adapt to climate change and expand clean energy). It becomes increasingly evident that treating the political only in terms of a relationship limited among humans is insufficient, and that all the world’s species, things and beings must be represented in a sustainable symbiosis or sympoiesis, i.e. in a making with (Haraway 2016, 58).

To “make the oddkin” is what Donna Haraway has called the realization of this urgent confluence of fluxes, introducing a quirky term that can ignite the imagination while alliances are reconfigured within a broad resistance to the bonds of the Anthropocene, the Homogenocene and the Capitalocene, of any epoch that signifies nature’s commodification and species’ destruction. While the old Green rhetoric (often hijacked by the corporate geoengineering lingo) has lulled us into addressing only the consequences of environmental destruction instead of fighting the causes beyond debilitating compartmentalisations, we have to learn again how to be truly present. We have to become nature defending itself, to think and act now “as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings” (Haraway 2016, 1).

This curatorial proposition is certainly one of the many recent attempts to investigate the visuality of this socially and politically oriented eco‑criticism. A series of curatorials, publications and conferences over the past five years have addressed ecology and eco-criticism in renewed terms and multiple viewpoints in their association with the arts. In his recent publication Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology, T. J. Demos has engaged critically with the ‘image complex’, the system of image production and circulation that frames, together with other legal-political-economic assemblages, the visual culture of environmentalism (Demos 2016).

What arguably made Paratoxic Paradoxes a proposition worthy of specific consideration and a visit was, to a great extent, its point of transmission — Greece — and the emblematic character that this point seems to have acquired for complex reasons and functions pertaining to (competing) ideologies, politics, economic constructs, and even artistic initiatives and new myth-makings. The most recent such example is the case of Documenta14 organized in both Athens and Kassel as a “divided self” with workers who “have been immersed in the city (of Athens) that has become emblematic of global contemporary crises”, as per the words of the artistic director Adam Szymczyk in the Documenta14 reader (Prestel Verlag publisher, 2017, p. 19).

“Sympoiesis is a word proper to complex, dynamic, responsive, situated, historical systems. It is a word for worlding-with, in company” (Haraway 2016, 58). It is also a Greek word.

A word of Hermetic order, to return to Michel Serres’s heaven, full of unsystematic, fluctuating, connecting, obscuring, troublemaking angels, and governed by the Greek god of communication and its obstacles, the founder of alchemy and bargaining wanderer “who makes sense and destroys it”. Michel Serres has been engaging with Hermes and the angels as free mediators and arguers in many of his works and most importantly (in relation to this text and its author: Serres 1995; Serres [1993] 2008).

Aphrodite and Hermes riding on a chariot pulled by Eros and Psyche, 470 BC, terracotta relief, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Taranto, Puglia, Italy.

Paratoxic Paradoxes comes as yet another unexpected transmission from such a chaotic, confused and confusing cosmos in dire need of generative practices, alternative imaginations and hybrid ecologies. We are convinced that such an act of transmission is useful precisely because it seems paradoxical, overstated, superfluous; a luxury, or even ‘pollutant’, wasteful, excessive, perittõ.

The Greek word for weather, kairos, carries in this language the additional weight of the meaning of a ‘crucial point’ of ‘time fulfilled by human intervention’, and so it joins the current global lexicon of eco-critical discourse almost like a memory from the future.

Greece is becoming the new-and-improved target of extractivist policies and their twisted logic of withdrawal — of labour, value, resources, time — from the land, its people and culture. The perfect storm that has overrun the country for the past seven years, pivoting in the refugee and financial crises, has proven to be the perfect breeding ground for malfeasance, injustice, a creeping and crippling socioecological disaster. In the context of precarious working realities, mounting fear in view of any change and the absence of critical debate and planning on issues of environmental protection and sustainable symbiosis in Greece, it is worth noting a very recent episode that involved the country’s biggest public sector operator, namely the Public Power Corporation (PPC): the GENOP/PPC trade unionists publicly announced, on World Environment Day nonetheless, that they aligned with the US decision to withdraw from the Paris accord and Trump’s claims that climate change is but a Chinese hoax developed by the mechanisms of ‘green’ corporate interests that work against the benefit and consciousness of people. Their announcement ended with a general call for “a green rehabilitation in lieu of a green development”.

Exhausted, albeit not-until-recently exotic enough to serve as the symbolic battle ground against neo-colonial advances, Greece has been re-colonized by the western imaginary at its weakest moment heralded anew as the promise of a queer future.

It has risen in the progressive world’s interest during its very slide to the toxic and the paradoxical (in both the literal and metaphorical sense) and while the ‘indigenous’ have turned into toxic progenies, poisoned by all kinds of polluting agents and hazardous materials: from garbage-management failures to deteriorating parliamentary practices and rotting public dialogues.

At worst, Greece has been used as the guinea pig of neo-liberalism; at best, it has been perceived and represented as the ultimate metaphor, the stage-par-excellence in a theatrum mundi of disasters where the aging, sick Capitalism is the only surviving author and its fragile democracy of misunderstandings feeds a weird repertoire.

The Paratoxic Paradoxes curatorial has not missed the joke created by the ambivalence of the toxic-waste/hazardous-management vocabulary. It decided to engage with this rather ominous, complex, damaged reality of a place ridden by the past and oblivious of any future, with a dose of black humour: to imagine the stage staged as the thick, ongoing chthonic presence in Haraway’s concept of Chthulucene – a term compound of khthôn and kainos that purposefully works as a metaplasm of Lovecraft’s invention of the Cthulhu mythos. This is “a timeplace for learning to stay with the trouble of living and dying in response-ability on a damaged earth” (Haraway 2016, 2).

Icon for the Chthulucene. Source: Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham & London: Duke, 2016.

If it is true that we are facing the dawn of a new settling of accounts, in which “necessity returns inside the concept of ‘us’” and “must equals cause, because we have become the authors of ongoing creation” (Serres 1995, 176–77), this exhibition can be understood as the outcome of such necessity; what the ancient Greeks would call anánkē, a word of ungraspable etymology and derivations such as ‘constriction’ and ‘kinship’ that actually coincide. In other words, if the underlying notion of the exhibition is the bond, then the exhibition was ‘bound to happen’, as we waste and are being wasted.

Paratoxic Paradoxes begun with a study of the physical parameters and effects, the symbolic, psychological and socioeconomic implications of two — seemingly simple yet quite vague and ambiguous — terms and the multifaceted reality they reflect: ‘toxic’ and ‘waste’.

It explored the parallel readings of the redundant and the rejected, of that which is manageable yet elusive, of the amorphous and the anarchic, the abundant and the dwindling, the repulsive and the repressed, the excessive and the grotesque, the viral and the virulent, the processed and the possessed.

The artists, who have engaged in the project, faced the unusual challenge of a minimal curatorial precept (toxic, waste) and maximum liberty in their chosen geographical, ideological or material approach.

In the course of two years, this creative approach acquired the form of analysis, dissolution, exploration, reversal, transmutation, rejection or study in the light of conflicting discourses, indigenous cosmologies, capitalist nightmares, scientific findings, artistic sub-genres and ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ theories of interaction between the human and the non-human.

Acting para-, that is "next to" and "beyond", the curatorial message, the artists jay-walked through languages and bodies. By radically distorting, influencing, mixing and combining, alchemically transforming their prima materia, they demonstrated the paradox of the very notion of (de)contamination beyond the obvious.

Their common medium was the ‘moving image’ as it expresses our relationship with the continuum of the world in novel, affective ways: thanks to its new composite varieties and spatial realizations (in link with performance, installation, sculpture); because of its fluid nature determined by time as much as by space, and shaped by both phantasms and materials; due to its ability to be readily available and widely transmittable and accessible. Strangely enough these very attributes are, in this age of techno-fixes and shallow info-bulimia, sources of an unprecedented image-data contamination which violently changes the very way we grasp the world and relate to those we share it with.

The Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition space embodied the project’s processes and questions, its facts and fabulations: It made the effort to weave the works’ idiorrhythmies into a form of interarticulate storytelling. It attempted to capture the tension between attraction and repulsion, desire and guilt, that the works spotted and highlighted within the environmental discourse at large; to respect those works’ nature of documentary fiction; to treat them as living bodies, rubbing, brushing against each other independently of this or any effort to read them together. This ‘rubbing’ of bodies is a potent, emblematic image of living/breathing bodies in a Greek ritual of joyful mourning, found in my favourite Andreas Embiricos work Eis tin Odon ton Fillelinon (written between 1942 and 1965 and published in the collection Oktana, Ikaros, 1980); I was very interested — in the context of thinking on curatorial formulae — to recently discover this image in Fred Moten’s and Stefano Harney’s writing and critical approach (as discussed during an interview with Adam Fitzgerald in 2015).

Appearing as a black pit, a coagulation of soft, absorbing materials, hard, structural edges, scandalous window-openings, various times, mixed noises, strange low hums and uncanny screen glows-in-the-dark, the exhibition space felt as a "shared presence in displacement".

It was a (disorienting/reorienting and absorbing) meditation on the paradox of the globality of localities; a curatorial (rather than an architectural) test of fading-in, as memories of things said and exchanged were being retold, delocalised, re-nested. It was a celebratory immersion in and substantiation of Fred Moten’s verses as they appeared in Wu Tsang’s work:

“The hazard of movement,

of moving and being moved.”

This space at the Benaki Museum, 138 Pireos Street, Athens, had a destabilising doppelgänger: a virtual dumpsite, designed as an online parasitic body (http://www.pcai.gr/1rstPhase_PP/PP_Main.html), which people were invited to read as Michel Serres’s “Stercorian Atlas”, a space of growing appropriation, a hip of networks, marks, stains and sign-posts. The project-related team (artists, curator, organizers, designers, various interlocutors) have been throwing in materials that challenged, or contaminated, the exhibition’s presence. Links, images, texts, references, indecipherable symbols, apparitions, unclean contradictions, piled up, anarchically, asymmetrically, subject to contingency and circumstance, so that those who entered could dig in and decide what to salvage, reuse, bury deeper or ignore in an exercise of dis‑appropriation through disposal.

Paratoxic Paradoxes curatorial project adopted a rather centrifugal approach as it reached out to artists of significantly different conceptual perspectives and practices not registered in any ‘environmental agenda’. It formed a family of disparate voices and thus put to the test its own call to action and its fundamental conviction that art bears the potential to animate ecological discourse with the force of new kinships and unpredictable tactics.

Vasilis P. Karouk, Prima Materia, animated HD video / installation on a 2’4O’’ loop, 2O16. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

Prima Materia by Vasilis P. Karouk is formed like a digital frieze, a moving superstructure whose perpetual narrative unfolds in a multiverse dimension. At the center of this narrative timescape lies an entity in the archetypal image of Terra or Gaia; maker and destroyer, a primordial complex of elements and phenomena with devastating power, this dominant and resilient figure could be an intrusive event that undoes thinking (as in Isabelle Stengers’s writings or the James Lovelock Gaia hypothesis) and puts into question our very existence as a result of its human-provoked mutation. The artist collected footage from forty different places with polluting activities around Greece and used it to compose, in painterly terms, a writhing body; a fragile synthesis of facts and fears.

Saskia Olde Wolbers, Pfui – Pish, Pshaw / Prr, two-channel HD video, 20’, 2017. Video still, courtesy of the artist.

Saskia Olde Wolbers’s fictional work’s title Pfui – Pish, Pshaw / Prr derives from a DH Lawrence quote in which the author abandoned language to express anger. Pfui – Pish, Pshaw / Prr is based on interviews with the longest-serving employee of Environmental Protection Engineering S.A., a Greek oil spill response company, Mr Theodosis Alifrangis. Stationed at the site of a sunken cruise ship on the Greek island of Santorini for the last ten years, Mr Theodosis has become the ship’s conscientious guardian, tending to the slow release of petrol and oil to protect the surrounding waters and marine life. An eclectic sample of his prolific 1990s VHS archive is presented here alongside footage shot in the artist’s studio of model sets of cruise ship interiors, ferromagnetic mussels and molecular structures submerged in tanks and covered in iridescently coloured dripping oil paints. The work also features imagery of sonar imaging attempts of the elusive cruise ship. The fictional script is from an oil spill responder’s point of view and reveals his superstitious reason for filming: xematiasma, the Greek oil and water divination, where his camera wards off the evil eye as for the last 30 years he has tended to major emergencies on a daily basis. He expands into further musings around matter and spirit, ancient rituals for cleansing the sea and purifying the natural element, his love for shipwrecks and recollections of heroic acts of protecting the environment against the mundane everyday reality.

Mika Rottenberg, Minus Yiwu, video on a ca-7’ loop, 2O17. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

Shot in China, more precisely along the miles upon miles of small retail shops in the vast market of the city Yiwu, where 70% of the global production of Christmas ornaments and plastic toys is being sold, Mika Rottenberg’s Minus Yiwu comprises an environment where the viewer is simultaneously placed before and inside a peculiar, psychedelic setting of colour explosion and synthetic bliss. In this tide of perpetual festivity, which rivals the bizarre dystopias of science fiction, working people appear apathetic, trapped in a contemporary myth with no characters or plot, attuned to the screens of computer terminals or mobile phones, engrossed in some other, dematerialized reality while buried in synthetic materials and the deadlock conflicts and promises of capitalism. In Rottenberg’s film installation, one has to walk through a veil made of ribbons, procured from the Yiwu market. Thus, the experience of the work is based on the permeability of yet another screen and the gradual transition from euphoria to disaffection, from enjoyment to disgust, as the perversion of the very material of life becomes perceived, embodied, unbearable.

Korakrit Arunanondchai, with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4, HD video, programming and installation, 23’31’’, 2O17. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

How do the technologies we have developed manage and distil (expel and preserve) our fragile memories and fickle experiences? What processes of lamentation are necessary for us to connect with the spirits of the world? Korakrit Arunanondchai’s work with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4 features many of the elements of his artistic universe, such as: the oversized rat that has survived the Apocalypse; the serpent-spirit Naga, symbolizing the spirit that does not surrender to the power of authority; and the drone-spirit Chantri, which speaks in the voice of the artist’s mother (a linguist) and enables a hypnotic dialogue about the possibility of rebirth, of reconnection with our lost self. The video opens with a close-up shot of the hands of the artist’s grandmother, who is slipping into dementia.

“The present has ceased to apply to me,” is the phrase that describes her amnesic mind, while Arunanondchai reflects on how we relate as species and unfolds the achronicities that throw our world into a vertiginous state. Aiming to draft a new deal with ancient Mnemosyne and understand the ‘extreme present’ we often experience, he focuses on specific events and sites (the recent anti-Trump demonstrations in America, the paleoanthropological site “Cradle of Humanity” in Africa, the death of the king of Thailand, the Buddhist temple Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Thailand).

The overall installation in the exhibition, formed using personal objects, family heirlooms and interiorly lit blown-glass pods, is attuned to the sound of a breathing whose nature is uncertain: does it suggest a state of panic or meditation? Is it a first or a last breath?

Eva Papamargariti, Always a Body, Always a Thing, HD video, sound, colour, 15’25’’, and cast rubber on custom-made steel parts; dimensions variable, 2O17. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

In Always a Body, Always a Thing, Eva Papamargariti starts from the emblematic texts of Roland Barthes about plastic, the anti-hierarchical magic substance with the alchemic properties of infinite transformation. She examines a series of bizarre incidents – actual or imagined – whose common thread is the ingestion and embodiment of plastic by living beings (fish, frogs) that end up mutating, as well as the appearance of a host of amorphous masses in natural settings (meadows, lakes). Her research centres on the way in which plastic (born from organic matter) returns to nature as non-biodegradable waste, having absorbed elements of life and time in the course of its transformations and wanderings, in a process of biophagy and tempophagy. Using moving-image tools (digital animation, 3D simulations, computer-generated soundscapes), as well as objects–sculptures, the artist introduces us to toxic progenies of the living world and to the queer futures they portend. As one of the critters in her video says: “Metamorphosis, concealment and adaptability are the tricks that keep us alive. We, a plethos […]. I am your creation. Your existence affected mine, now I am affecting yours. Becoming the horror, the mutant, the incomplete, defective in form, balancing between extreme endurance and unpredictable fragility”.

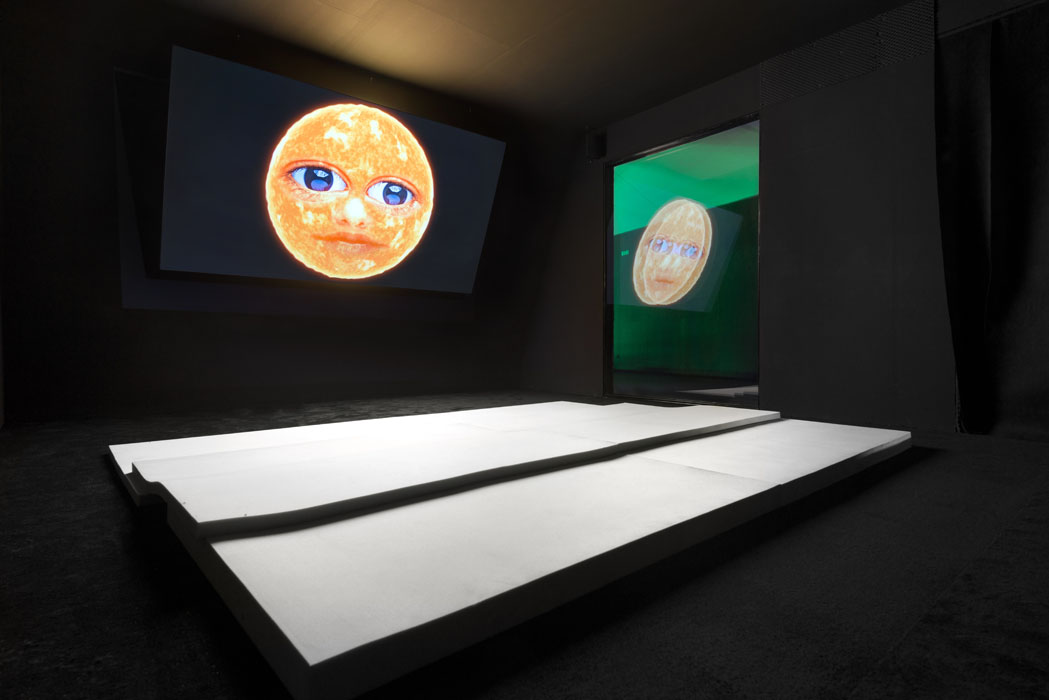

Agnieszka Polska, What the Sun Has Seen, HD animation, 1O’, 2O17. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

The film What the Sun Has Seen, by Agnieszka Polska, borrows its title from a poem, in a realist style, that recounts the quotidian life in a childish manner, peaceful rural activities and happy family life of the Polish nation, as observed by the sun on its daily journey across the sky. Polska offers her own dark, ironic version of the poem, as her sun follows the course of routine web surfing, going through sites of conspiracy theories, porn, cute pets, social networks, noble nature and mass culture. The ominous feeling of pollution-by-information is consolidated in the flurry of images, even if these are temporarily pleasant or paradoxically alluring. “I have seen the beauty of such greatness, that I could not find the language beautiful enough to describe it. My gaze was moving at a constant speed, and everything was becoming irreversible the moment I observed it”, we hear Polska’s sun say. With this reference to the most updated quantum theory – according to which merely by observing phenomena we 'lock' them in time and place – this work conjures the melancholic phantom of Walter Benjamin’s “Angel of History” and confronts us as observers of nature and culture in past, present and future.

Loukia Alavanou, Bananaland, single-channel HD video with sound, DCP, 16’3O”, 2O17. Video still, courtesy of the artist.

The film Bananaland by Loukia Alavanou comprises footage shot in the small farming village Los Angeles in South Ecuador, images from the historical propaganda dioramas in the museum of Guayaquil and a mixture of images and sounds from 195Os American children’s documentaries and TV series, such as Journey to Bananaland. The artist began her research from regions in Ecuador — the first country to recognize the rights of nature in its constitution — where Polyeco group, a hazardous waste management company, has undertaken to remove the toxic pesticides formerly used in agriculture. In the film, the impact on the life of the locals and the behaviours and practices that propagandize for the presence of Western interests at the expense of indigenous communities are perceived as examples of a kind of ‘toxic colonialism’ that harms life itself far beyond any damage to the natural environment. In the film, the parasitic attributes of such practices are also highlighted through sound, which is treated as an extra composite material created by an allegorical recycling of elements drawn from many different sources of pop culture. Alavanou questions the very gaze of the artist who intervenes and represents while often becoming a kind of ‘waste picker’ participating in the alternative ways of cultural economy and ecology and preserving what is rejected by the institutional or economic practices and the official rhetoric.

Eva Kot’átková, Stomach of the World, video, 44’5O’’, 2O17. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

The film Stomach of the World by Eva Kot’átková functions as an anatomical theatre where the allegory of the world as a body, is enacted in exercises and dialogues. The stomach of the world is but a chaotic dumpsite, a ravenous machine that devours the accursed share of human presence starting from the tender ages of childhood, which, as in all of Kot’átková’s works, are exposed to the corrosive processes of education and compliance, control and correction. The body operation is ensured by anonymous human co-workers in a vicious, mindless circle of over-production/over-consumption. Acting anatomy and autopsy through a series of pedagogical games, the children (and the artist) as archivists of the functions of the stomach, trace the image of body politics, from ancient Greek thought (the Ouroboros serpent eating its own tail in Plato’s Timaeus, 360 BC) to 16th century literature (François Rabelais' giant Gargantua – a symbol of the voraciousness of capitalism) through to recent manifestations of the body social (scenes from the 'Pots-and-Pans' public protests around the world are alluded to in the film by child actors performing in a landfill, with thrown-away objects on their heads).

As the voice-over reminds us: “We stuff ourselves indiscriminately with anything to hand. We don’t think about the fact that by overfilling the stomach the performance might end. […] However, not everyone has a positive experience of a life of freedom. There are mice that prefer the body of a snake”.

Anja Kirschner, Moderation, HD video, 143’, 2016. Video still, courtesy of the artist.

Set in Egypt, Greece and Italy, Anja Kirschner’s Moderation revolves around a female horror director and her collaborators, whose latest project is haunted by encounters with its ‘raw material’, the escalation of conflicting desires and the way horror traverses the realities of their lives on and off screen. Much of the film is shot handheld, combining low-fi special effects with HD camcorder, Skype and mobile phone footage, in order to heighten the sense of immediacy and interplay between fictional, factual and genre elements. In line with certain tendencies in horror cinema from cold-war Europe, Infitah-era Egypt and post-junta Greece, lived experience is neither naturalistically represented nor sublimated by recourse to the irrational. Rather, the ‘irrational’ is used to externalize and de-subjectify what ‘haunts’ the protagonists, in order to reground the possibility of rational agency operating at its limits. Kirschner’s curiosity is also directed to the way that horrors (such as history, politics, climate, circumstance) grasp the age-old, rich and complex cultures of the Mediterranean shores — where the film is made — and throw them in a whirlwind of changes; yet her attention is tuned to the sheer energy released in such cases; the possibilities unearthed in this excess of the abject, the raw and the wasted; the networks jumpstarted by such possibilities.

Sophia Al Maria, The Magical State, single-channel video, 6’9”, 2O17. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

Sophia Al Maria, who has repeatedly expressed her mounting fear vis-à-vis the environmental collapse caused by the excesses of early and late capitalism, was led by her research to the region of La Guajira, Colombia, near the borders with Venezuela, the site of one of the largest open coal mining facilities in Latin America and one of the most afflicted areas on the planet in the course of the industrial revolution and globalization. The film The Magical State explores the extraction of fossil fuels from the desecrated land as a kind of ritualistic, violent exorcism imposed on the abject ‘female’ body. A young girl of the ancient Wayuu tribe, who speaks the ancient matrilineal language of her people, is being possessed by the spirit of crude as this has been conjured and exploited through human intervention.

Employing the genre/trope of an allegory and matching an uncanny psychedelic colour spectrum (that can be found both in the reflections of organic oil and the synthetic languages of the virtual world) with an overpowering music composition by James Kelly and a mesmerizing monologue in Wayuunaiki, Al Maria conjures an image of time-place and humanity that is both archaic and futuristic, magical and realistic, horrific and radiant.

Wu Tsang, we hold where study, two-channel HD video, stereo sound, 19’, 2O17. Installation shot at Paratoxic Paradoxes exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens 2017. © Yiorgis Yerolymbos. Courtesy of the curator and PCAI.

Wu Tsang’s short experimental film we hold where study takes a choreographic approach to image-making and mourning. The film enacts a series of duets, both within and between images, featuring choreography made by children, with Josh Johnson and by Ligia Lewis and Jonathan Gonzalez, both to original music by Bendik Giske.

The work is rooted in Tsang’s ongoing dialog with collaborators Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, authors of The Undercommons, and in particular on their recent essay called Leave Our Mics Alone. This essay posits an (im)possible set of images of resistance, through poetic notions of blackness (and/or transness and/or queerness) as an improvisational mode of being, in common with others, working through and of the environment. Considering one of Moten’s analogies, if constructions of Western/European whiteness can be understood as the set of (separate, individual) interpersonal relationships, then one can propose a notion of blackness (and/or transness and/or queerness) as being the entanglement. Entanglement is unavailable to the image. But at the same time, entanglement has the potential to manifest in every image. It cannot be depicted but at the same time it infuses the image. Wu Tsang’s film seeks passage to sociality through the opening of impossible images. What if the camera was not an omniscient eye or master narrator — but instead just another element of the entanglement? As the artist points out in her notes on a conversation with Moten: if we want to talk about the socio-ecological disaster, images of violence and planetary destruction might first come to mind. But we could also talk about autophagy (the process that allows the orderly degradation and recycling of cellular components), and the idea that the structure and the nature of life is violence to itself, a constant degeneration and regeneration. What if we were to understand violence not simply in terms of attacks on black and trans bodies, or toxic waste eroding the earth, but in terms of differentiations of violence? In terms of an ethics of sustainable destruction? What kind of interventions can today cut through the usual representations and understandings of 'the environment'? As Wu Tsang proposes with her work, what is urgent now is not to address tragedy, but to talk about how we live. What we need is a lot of ‘reverse-engineer’ thinking, a lot of inverting of powerful formulations that entrap imagination.

Paratoxic Paradoxes virtual dumpsite, screen shot. Image in reference sourced from: Michel Serres, Malfeasance. Appropriation through pollution?, translation by Anne-Marie Feenberg-Dibon, Stanford University Press, 2011.

Bibliographical references

- Demos 2016

T.J. Demos, Decolonizing Nature. Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology, Berlin 2016. - Haldane 1927

J. B. S. Haldane, Possible Worlds and Other Papers, London 1927. - Haraway 2016

D. J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham & London 2016. - Serres 1995

M. Serres, Michel Serres with Bruno Latour Conversations on Science, Culture and Time, translation by Roxanne Lapidus, Michigan 1995. - Serres [1993] 2008

M. Serres, The Five Senses. A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies, 1993, translation by Margaret Sankey and Peter Cowley, London & New York 2008.

English abstract

The exhibition Paratoxic Paradoxes was curated by Nadja Argyropoulou, and presents works she commissioned for the Polyeco Contemporary Art Initiative (PCAI) between 2014 and 2017. The exhibition was organized by PCAI and the Benaki Museum in Athens, Greece (23 March – 21 May 2017). Exhibition coordination: Loraini Alimantiri. Exhibition design: Nadja Argyropoulou with Malvina Panagiotidi. Virtual dumpsite design: Vassiliki Maria Plavou and Eva Papamargariti. Graphic works: Em Kei. The text, From Paratoxic to Paradoxes (and vice versa), is a walk through the curatorial idea and a presentation of the exhibition.

keywords | Exhibition; Queer; Nature; Contemporary art; Athens; Benaki Museum.

Per citare questo articolo/ To cite this article: Nadja Argyropoulou, From paratoxic to paradoxes (and vice versa). Presentation of the exhibition at Benaki Museum, Athens, in “La Rivista di Engramma” n.146, giugno 2017, pp. 103-122 | PDF