Dionysus and the Acrobat

Study, Conservation and Promotion of the Lipari Necropolis Kalyx-krater

Lorenzo Lazzarini (Laboratorio di Analisi dei Materiali Antichi, Università Iuav di Venezia)

Francesco Mannuccia (L’ISOLA laboratori di restauro s.r.l.)

Umberto Spigo (Former Director of the Parco Archeologico delle Isole Eolie)

English Abstract

Versione italiana

1 | Claire Lyons, Curator of Antiquities of the Getty Museum, in front of the krater with Dionysus and the Acrobat from Lipari.

Dioniso seduto e dinnanzi a lui una acrobata nuda e due attori di commedia. […] Ha una corona di foglie d’edera […] e il lungo tirso che si appoggia alla spalla. La giovane acrobata […] si esibisce in un esercizio tenendosi con le gambe all’insù, e flesse […]. Dei due buffoni che occupano il lato destro della scena, il primo piccolo e tozzo con capelli e barba bianca e con corta exomis […] si curva con le mani sulle ginocchia per ammirare più da vicino le bellezze dell’acrobata […]. In alto da due finestrelle appaiono altri due personaggi pronti ad entrare in scena, entrambi con maschera bianca e quindi probabilmente femminili.

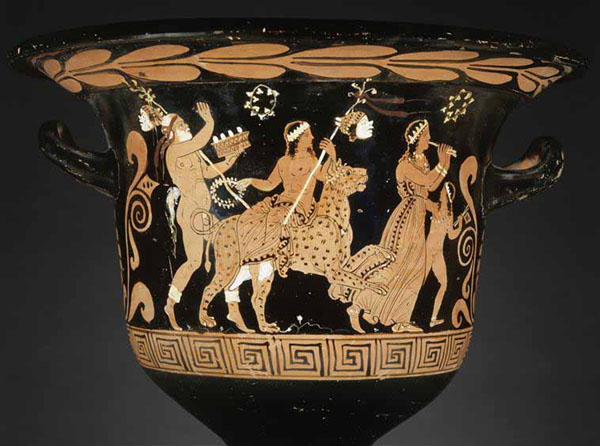

Dionysus seated and before him, a nude acrobat and two comedic actors. […] He has a crown of ivy […] and the long thyrsus he rests on his shoulder. The young acrobat […] displays his body in exercise with her legs raised and flexed […]. Of the two jesters who occupy the right side of the scene, the first, small and stocky, with white hair and beard and a short exomis […] bends over with his hands on his knees to better admire the beauty of the acrobat […]. Ahigh, from two small windows, another two characters appear ready to enter the scene, both with white masks, therefore probably, female.

Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1965, 131

2 | Poster of the exhibition held in Los Angeles, Getty Villa, April-August 2013.

Thus did its discoverers, Luigi Bernabò Brea and Madeleine Cavalier, describe the main scene of this phlyax calyx-krater in Meliguni Lipàra II. The vase, probably by a Sicilian workshop, is part of an important group of works that underwent highly sophisticated analysis and restoration arranged by the Getty Trust of Los Angeles. The restoration project, carried out on the occasion of the exhibition "Sicily. Art and Invention between Greece and Rome" (figs. 1-2), was determined necessary for the future safeguarding of the work. As highlighted by the curators, the exhibition's deliberate selection of 150 archeological finds intended to “shift […] focus to the Classical and early Hellenistic periods, when Sicilian Greek achievements in art and architecture, poetry and rhetoric, philosophy and history, and mathematics and applied engineering, attained levels of refinement and ingenuity rivaling, even surpassing, anywhere in Greece” (Lyons, Bennet, 2013, 2-3). With the approval of the Sicilian Ministry of Culture and Sicilian Identity, the exhibition travelled from Los Angeles to Cleveland in 2013[1].

3 | Visitors of the 2013 Getty Villa exhibition.

Over 140,000 visitors played a vital role in the process of promoting Sicilian archaeological heritage [Fig. 3] in an initiative that was followed in 2016 by the exhibitions organized at the British Museum and the Ashmolean Museum (Booms, Higgs, 2016; AA.VV., 2016).

The three events – significant examples of cultural interaction at an international level – resulted in the development of research programs aimed at deepening the knowledge of both ‘artistic techniques’ and the impact of preservation measures from previous restorations of the single masterpieces[2]. As will be discussed in this paper, these events, far beyond the occasioning contingency, “stimulated a reappraisal of ancient Sicily’s contributions to classical culture,” a reappraisal that “can ramify in unexpected directions” (Lyons 2014, 258, 260).

The themes of promotion and conservation of cultural heritage through preparatory diagnostic processes are in line with the conceptual approach of Pots&Plays, a research topic of "Engramma" and the Centro Studi ClassicA at the University Iuav of Venice. In fact, the Lipari krater, "pezzo di eccezionale interesse per la storia del teatro antico" (“an object of exceptional interest for the history of theatre in antiquity”: Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1997, 40), and its conservation issues, were granted special attention during the Pots&Plays seminar held in Venice on May 16, 2017 as a exchange between the Iuav and the Getty.

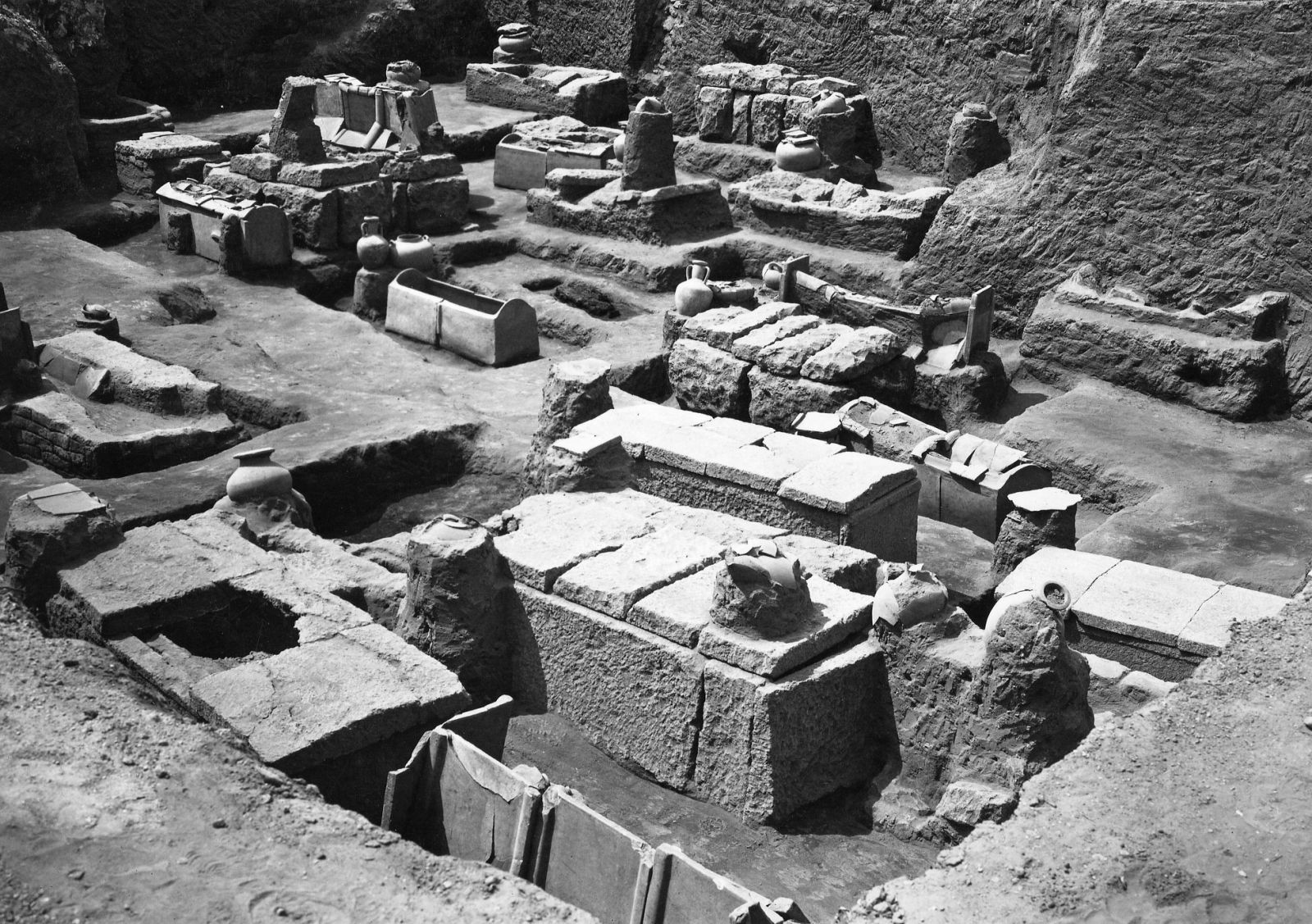

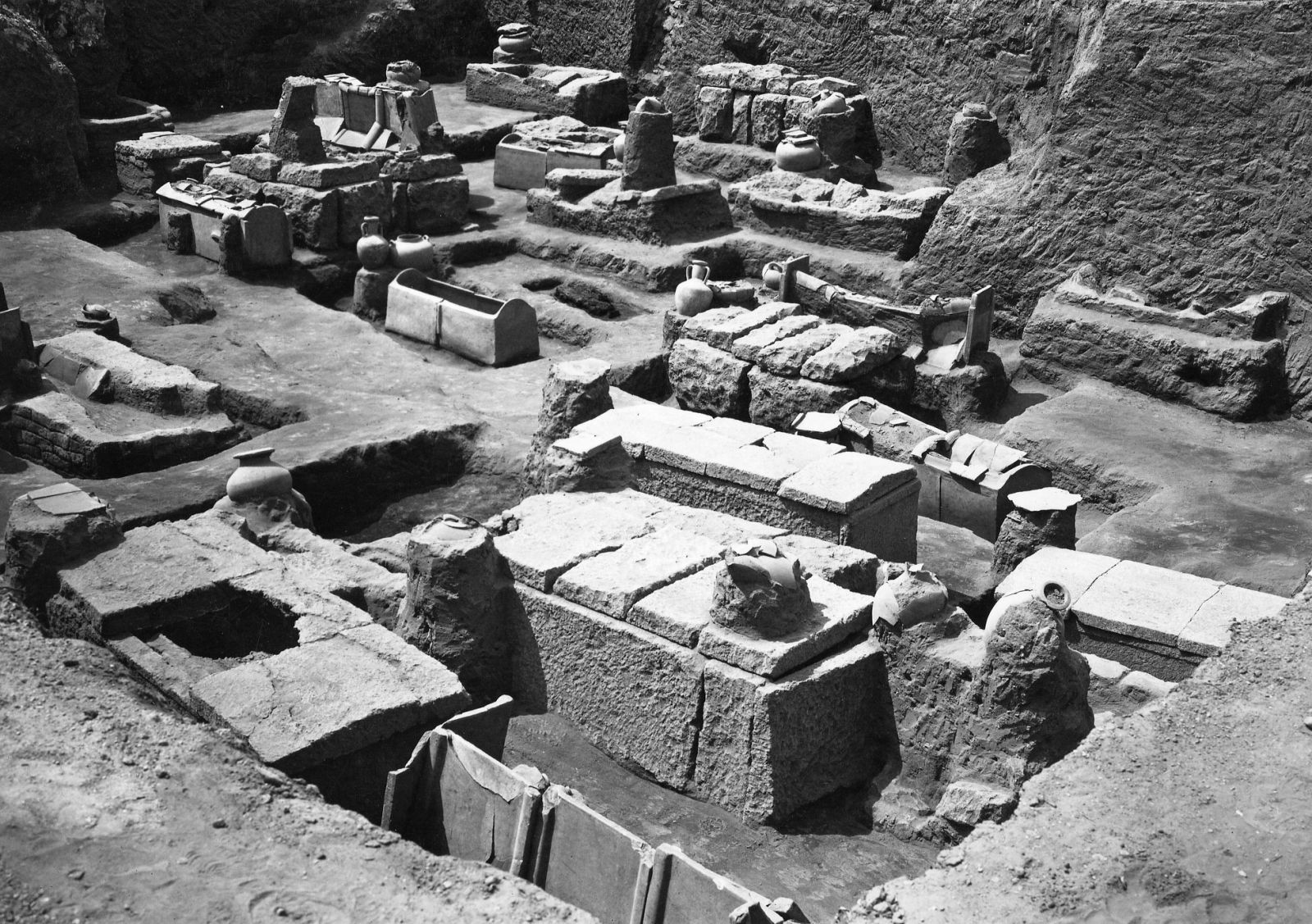

4 | Lipari, necropolis of Contrada Diana during the excavations of the 1950s (from Bernabò Brea, Cavalier 1965, plate XXXI).

The krater was discovered in August 1954 (Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1965, 131) in a burial cist built with unfired bricks in the Greek Lipàra necropolis of the “contrada Diana” on the island of Lipari [Fig. 4]. Evidence shows that it was used as a cinerary in the burial chamber of the necropolis (Tomb 367, excavations by the Soprintendenza alle Antichità of Syracuse curated by Luigi Bernabò Brea and Madeleine Cavalier). The uniqueness of the iconography in the figurative scenes on the main side, and the extraordinary expressive power of these scenes, have rightly placed this masterpiece – attributed to the Group Louvre K240 (Trendall 1987, 42-66, n. 91; Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1997, 38-46; Roscino 2012, 287-295) – among the most emblematic of the Western Greece red-figured pottery said to show the links between Dionysian devotion and the theatrical universe (Pontrandolfo 2000; Schwarzmaier 2011).

5 | Video-microscopy examination of the state of conservation of the krater.

In 2012, technological analysis were conducted on the krater with the help of video-microscopy [Fig. 5] in order to evaluate the real state of conservation before it would journey across the Atlantic for the Getty exhibition. These tests found that, for conservation purposes, it would be necessary to conduct a delicate operation that could not be carried out without dismantling the artifact itself.

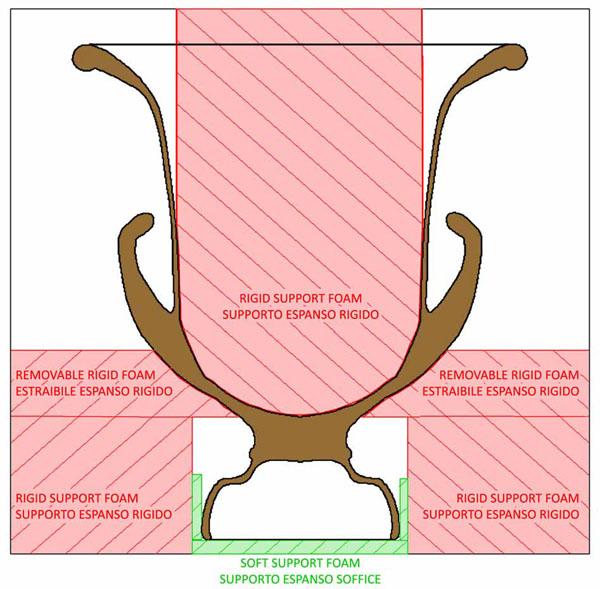

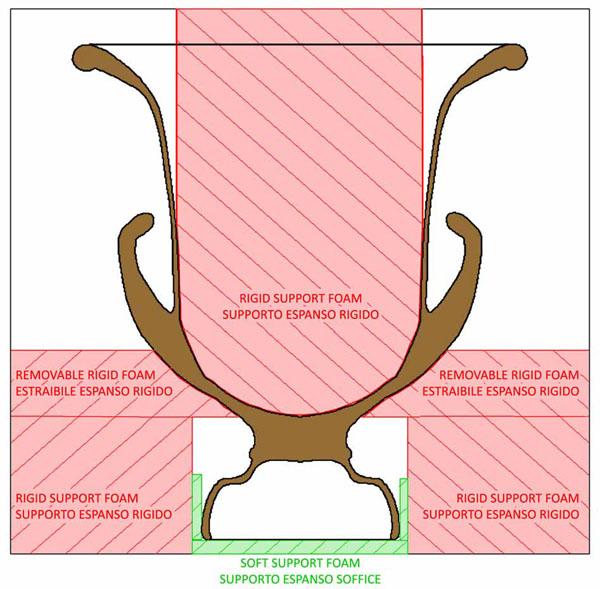

6 | Packaging design for the krater proposed by the Getty.

Despite being protected by the packaging especially designed by the Getty’s technicians for the physical transfer of the object [Fig. 6], the risk of collapse of the walls appeared more than likely, due to the poor state of preservation of the shellac used in the 1960s as an adhesive to assemble the 48 fragments composing the vase.

Faced with the understandable refusal of the Museum of Lipari to allow the krater to be handled due its precarious conditions, the Getty Museum offered to take the financial charge for a radical updated restoration, what could be called a 'trial' intervention for the consequences it is expected to have on the more general conservation of the vascular and coroplastic heritage of ancient Sicily[3].

7 | Ancient lead 'puntature' on an Attic krater from the necropolis of Lipari, Museo Archeologico Regionale “Luigi Bernabò Brea”, room XXI.

In our case, the main conservation question involved has proved to be the decision to use shellac in earlier restorations: its ageing involves vitrification and subsequent loss of adhesivity. The phenomenon unfortunately affects most of the artifacts in the display cases of the most important Sicilian archaeological museums (Siracusa, Palermo, Gela and Lipari). At the time of the Getty exhibition, no experiments had yet been made to resolve this problem.

It should be emphasized that this natural polymer, whose application in the restoration of archaeological ceramics dates back to the nineteenth century (Thiaucourt 1865, 9-13), was still in use in mid-century among conservators employed by the Sicilian Archeological Superintendencies like that of Syracuse. The maintenance restoration of pottery is documented in Sicily (and elsewhere) in numerous examples of the practice called "puntatura" in Italian, which consisted in using a bow drill to make holes in the terracotta inside of which were inserted metal staples or wires that, in the earliest cases, it is assumed were of organic matter (Ris Paquot 1876) [Fig. 7]. There is evidence of this technique from as early as prehistory to the early twentieth century "conciabrocche" character, Zi' Dima Licasi, in Luigi Pirandello’s short story The Jar (1909) who struggles to make Don Lollò accept the validity of the “mastice miracoloso, di cui serbava gelosamente il segreto" ("miraculous glue he kept as a jealously guarded secret”).

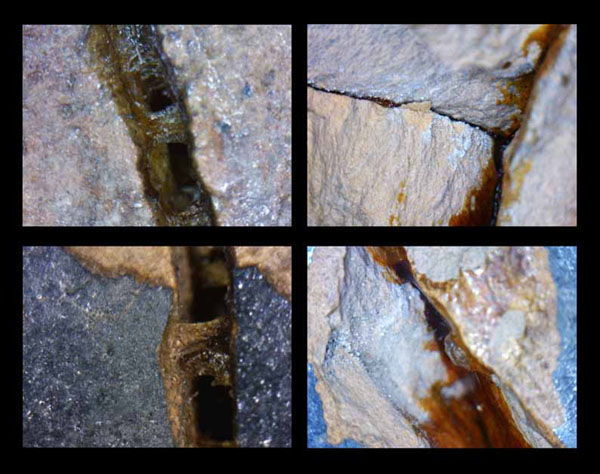

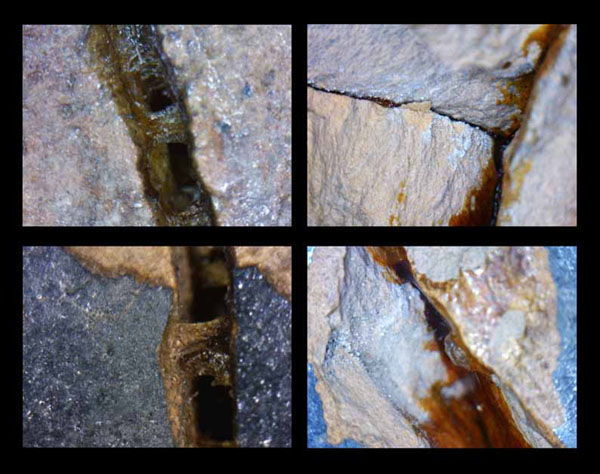

8 | Micrographs of the detachments in the krater.

Close examination detected not only the macroscopic separation of glued fragments [Fig. 8], but also showed the chalice was tilted a few degrees with respect to the vertical line of its foot.

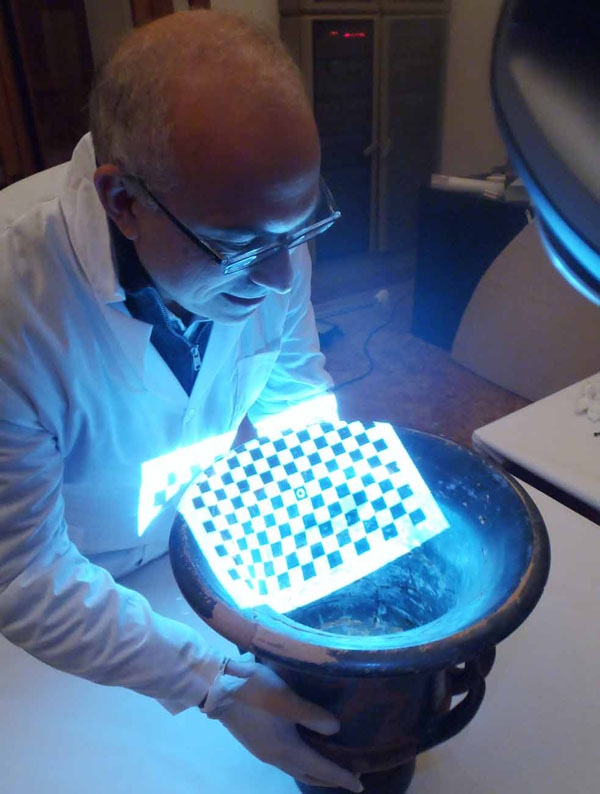

9 | Basin for exposure of the fragments to alcohol vapors ('Pettenkofer system').

Following a precise plan for dismantling the vase, its disassembly was possible thanks to an experimental approach based on the 'Pettenkofer system'. This method was developed by the German chemist Max Joseph von Pettenkofer in the mid-nineteenth century for a very different purpose (Secco Suardo 19274, 407-421; Piva 19722, 181-187): it used alcohol vapors to 'rejuvenate' weathered varnishes and restore legibility to oil paintings. Making use of its chemical-physical principles, it is possible to force aged shellac to swell, allowing its removal [Figg. 9-10].

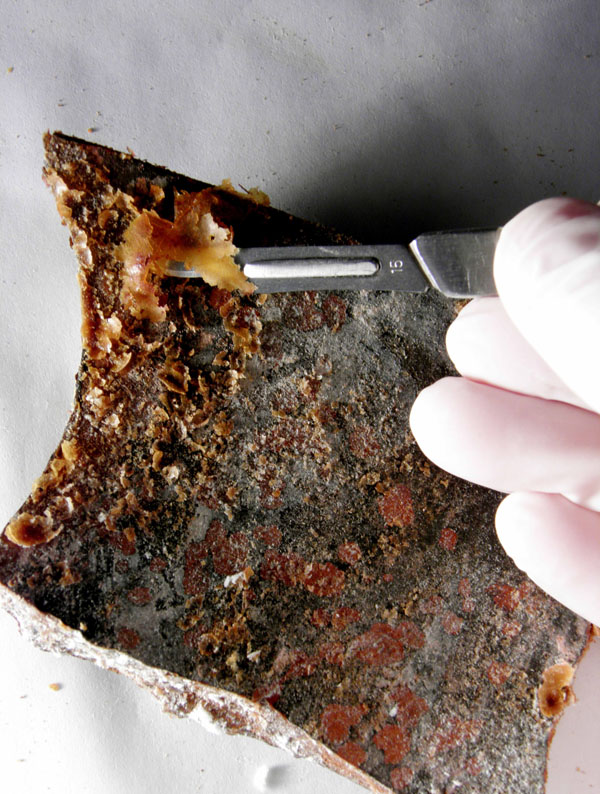

10 | Scalpel removing swollen shellac used in previous restorations.

11 | Dismantled fragments of the the krater's lip.

Due to the complex articulation of the crack pattern, it was necessary to develop a strategy for the reassembly that proceeded by separate sections [Fig. 11]. Adhesives with different characteristics (Agnini-Lega 1999; Castro-Domenech 1999, 114-131) were employed to glue together the fragments of the various registers of the krater, to provide a proper solution to the specific need of the lip, the figured zone and its concave lower wall, on one side, and to secure its foot on the other side. Fortunately, the section corresponding to the krater’s vertical wall comprised a single large fragment, a sort of continuous cylinder.

12 | The phase of gluing fragments following a precise reassembly strategy.

This made it possible to achieve a perfect bond among 48 fragments [Fig. 12], an indispensable prerequisite that guaranteed structural stability to the reassembled krater. It also restored the vertical axis of radial symmetry that had been deformed by a considerable thickness of shellac at the attachment of the foot to the belly, leading to noticeable misalignment [Fig. 13].

13 | 3D scanning ('Mephisto system').

14 | Chemical cleaning with ionic-exchange resins.

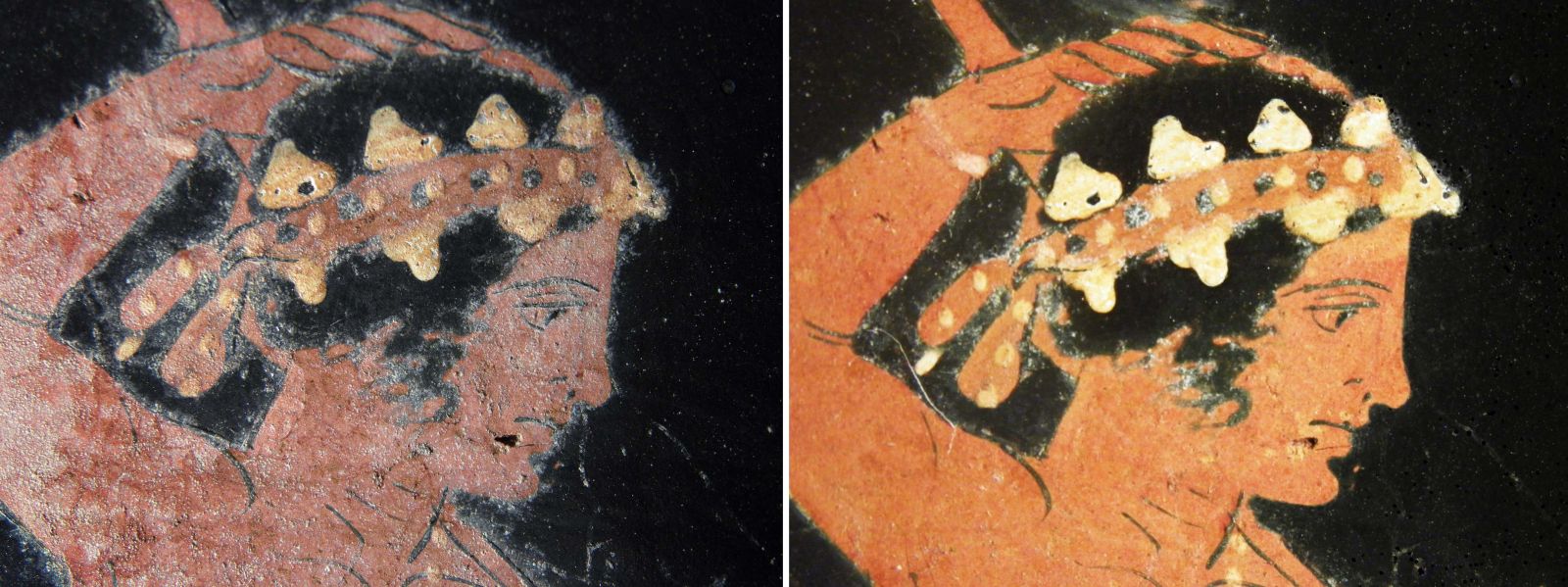

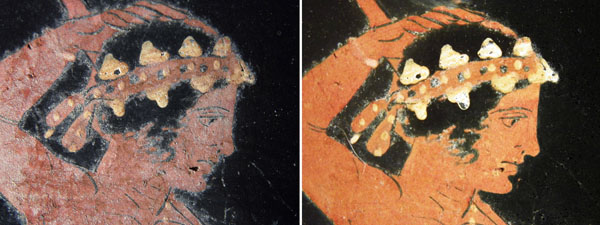

Cleaning was conducted both mechanically with scalpels and other precision tools [Fig. 14], and chemically with ionic-exchange resins (Pedelì-Appolonia 1998; Cremonesi 2001). The cleaning process aimed at the elimination or reduction of all disturbing addictions, including calcareous incrustations and the brownish gum arabic that obscured figurations [Fig. 15]. The coloration was later brightened with final protective treatments.

15 | The profile of Dionysus before and after the removal of calcareus incrustation and altered gum arabic.

16 | Top-view of the krater with recognisable fillings and integrations.

To restore material continuity and formal integrity to the work, the lacunae in the ceramic body – which in many cases involved the entire thickness – have been reconfigured [Fig. 16] with fillings and integrations in accordance with the principle of recognisability (Bandini 1992, 223-230; Pedelì-Appolonia 1994, 131-17).

Laboratory analysis – preliminary to identifying the most appropriate restoration methods – could prove an exciting starting point for developing interesting hypotheses for interdisciplinary work. Archaeometrical analyses crossed with the characterization of both the original clays used for the ceramic body and its decorative handles, as well as its original pigments, may generate new data on the production areas and markets of the large groups of vase painters active in the late classical age between Sicily and southern Tyrrhenian Italy. This group of artists is referred to as the “Sicilian forerunners” and, in the classifications established by Arthur Dale Trendall, is described as being active during “the transition from Sicilian to Paestan school” (Trendall 1987, 22-56; Denoyelle-Iozzo 2009, 166-170,181-183), a period which also includes the Group Louvre K240 (Trendall 1987, 42-46; Denoyelle-Iozzo 2009, 181-183; Denoyelle 2012, 32, 66-76).

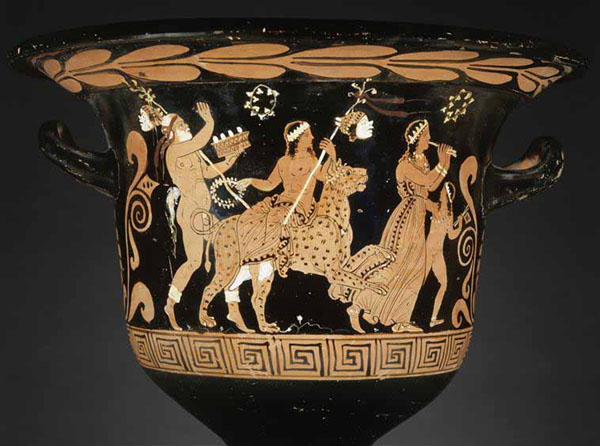

17 | The so-called 'Fleischman Krater' preserved at the Getty.

An expansion of the project that is in the process of being drafted will add other analyses requested to the LAMA laboratory by the Getty, so as to compare the ceramic body of our vase with that of the Getty Museum's calyx-krater attributed by Trendall to the same Group Louvre K240 (Trendall 1987, 46, n.101; Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1997, 38-46; Roscino 2012, 287-295). The so-called ‘Fleischman proto-Paestan krater’ is decorated with a scene depicting a Dionysian dance in which the god himself participates in the guise of a lyrist, and Eros is carried on the shoulder of a Silenus playing the aulos. The presence of an old phlyax with two torches makes reference to the world of theater [Fig. 17].

18 | Packaging of the krater in Lipari for the transfer to the Getty Museum in 2013.

The restoration was thus not only important for having averted the significant risk that could have been incurred by the handling of the archaeological find [Fig. 18]. Representing the restoration project in such a manner would undermine the importance of the Getty Museum’s initiative, interpreting it as an undertaking carried out merely to attain the loan of a masterpiece whose absence would have affected the attractions at the museum’s exhibition.

Instead, its positive effects must be evaluated and read as an example of the fruits of a cosmopolitan policy of openness to interchange between institutions that has long been practiced by the Getty Trust with the aim of increasing knowledge while enhancing cultural heritage, all in the context of great exhibitions organized upon solid scientific grounding.

19 | The eponimous krater of the Group Louvre K240, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

This conservation project offers an opportunity for comparative analysis of technical and stylistic data, as well as of iconographic heritage and its ideological substrate, not only with the Phlyax vases categorised under the Group Louvre K240 but with other important pieces as well: from the eponimous 'Louvre bell-krater' exhibited in the French museum [Fig. 19] and the three Lipari calyx-kraters of various Dionysian themes - the figurations in at least two of them (from tombs 921 and 974) show clear references to the world of theater, though through different indicators [Fig. 20] - to the calyx-kraters of the Getty Museum (Trendall 1987, 96, n. 101; Green 2012, 322-339, n. 55), the krater of Taranto (Trendall 1987, 46, n. 100) and the rhyton from Syracuse (Trendall 1987, 47, n. 103).

20 | The showcase of the Museo Archeologico Eoliano "Luigi Bernabò Brea" (room XXI) with the kraters of the Group Louvre K240.

21 | Side A of the krater with Dionysus and the Acrobat.

In fact, the return of legibility in drawing and color values also serves as an effective 'medium' towards a more complete appreciation of the expressive complex inscribed on the artefact’s surface, the significance of which is inseparable from the technical expertise of the vase painter, based as it is on the interaction between descriptive elements borrowed from the theatre and the metaphor of the centrality of Dionysus and his multifaceted cultual universe [Fig. 21]. It is thus that interpretative readings like those of J. Richard Green are given force, successfully capturing the 'key point' of the figuration as found “in the ambiguity between the actuality of performance and the further reality involving the god’s presence” (Green 2012, 321-323).

However, a more pointed attention to the role of this Group in the diffusion of iconographic solutions and stylistic accents in the Tyrrhenian area – in specific, around the actual configuration of relationships among these in the early productive phases of the Paestan workshop, particularly in the work of Assteas – requires broader knowledge of contextual data (both thanks to desirable new excavation acquisitions as well as through the revision of old discoveries) for the purposes of chronological framing. At the moment, associations with the forms of black-glazed ware that are present in the four Liparote funerary chests would point to the beginning of the second quarter of the century, deviating from the dating proposed by Martine Denoyelle by at least a decade (390-380) (Denoyelle 2011, 32, 66-76).

At the same time, identification of the center (or perhaps centers) of production remains entirely open by virtue of the undoubted projections of the Tyrrhenian area between Paestum and Campania; it has at times been proposed as a plausible, though still not scientifically-supported, base location between the area of the Strait of Messina (preferably the Sicilian shore) and Lipàra (Spigo 2002, 277).

The crossed previously-mentioned archaeometric investigations could lead to the development of this theory.

A series of laboratory analyses took advantage of the fact that during the process of unglueing pieces of the vase, a small flake of the ceramic body happened to separate from the surface, becoming irreplaceable. The analyses performed on the flake were carried out according to a programmed sequence so as to obtain the maximum of information possible from the materials constituting the krater and from the manufacturing technique followed in its execution (Cuomo di Caprio [1985] 2007; Lazzarini 2000, 283-290)[4].

22 | Electron microscope room at the LAMA laboratory, Iuav University of Venice.

A portion of the flake was powdered in agate mortar and subjected to X-Ray diffractometric analysis (XRD). The residues of glue adhering to the flake were removed with a scalpel and subjected to a Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) [Fig. 22]. The rest of the flake was then used for the preparation of a polished section. Upon incorporation into a cold setting polyester resin, it was later subjected to quantitative chemical analysis by means of scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive spectrometry (SEM+EDS). Finally, a thin section was formed from the glossy section and studied petrographically under a polarizing optical microscope. The results of all these analyses will be published elsewhere alongside those obtained by similar methods from the study of the sample of the aforementioned 'Fleischmann proto-Paestan Krater' sent to the LAMA laboratory by the Getty.

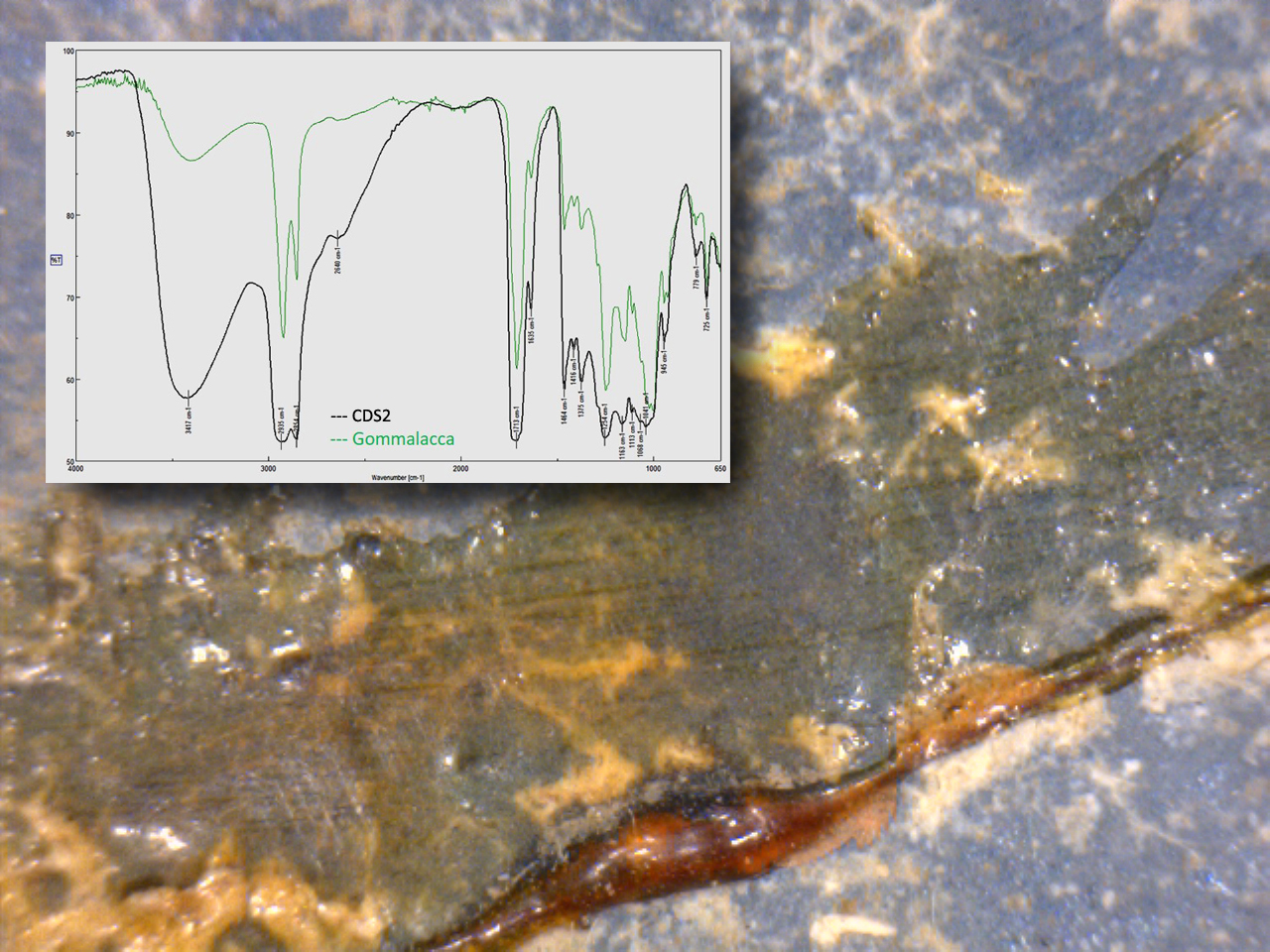

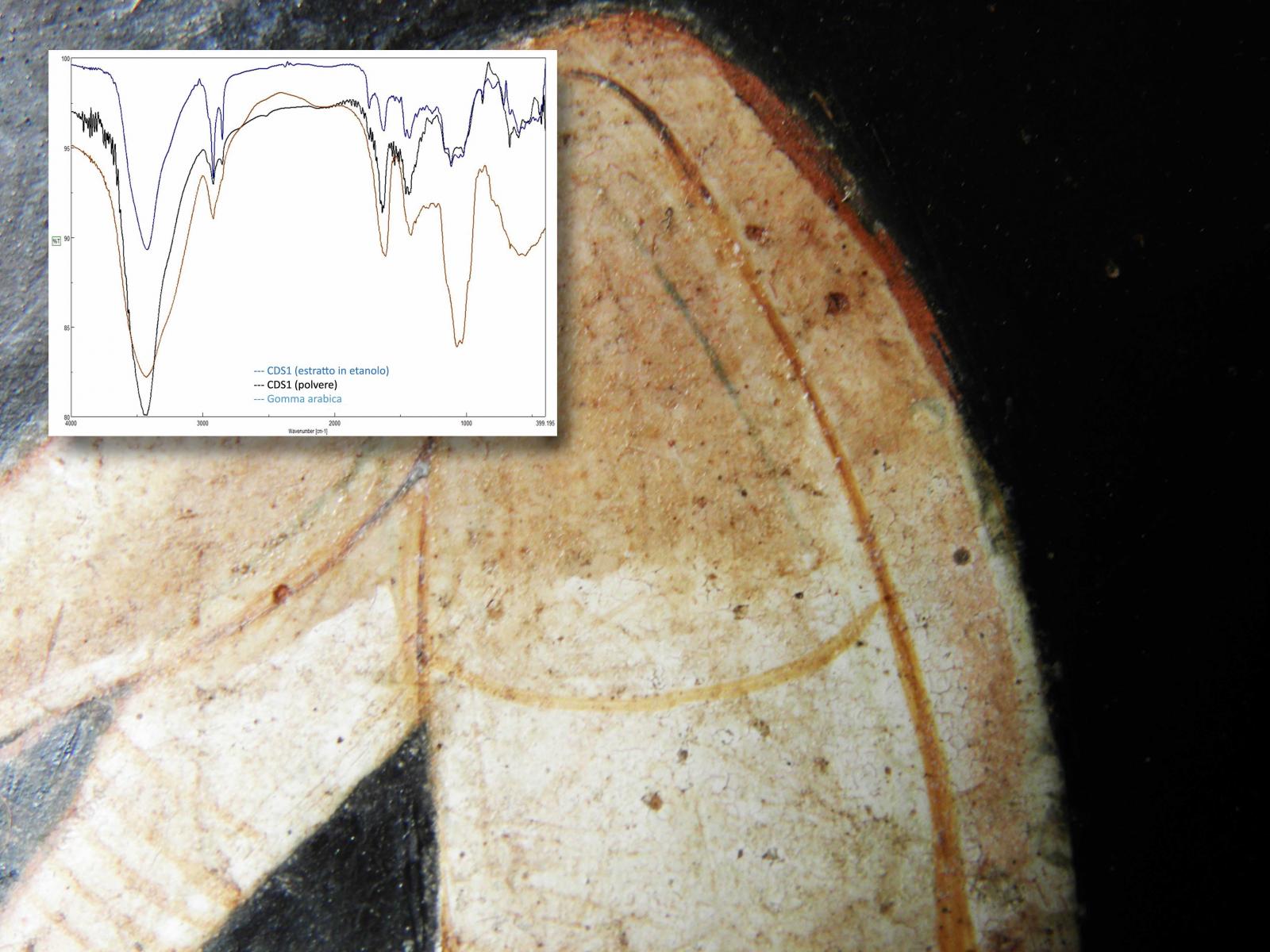

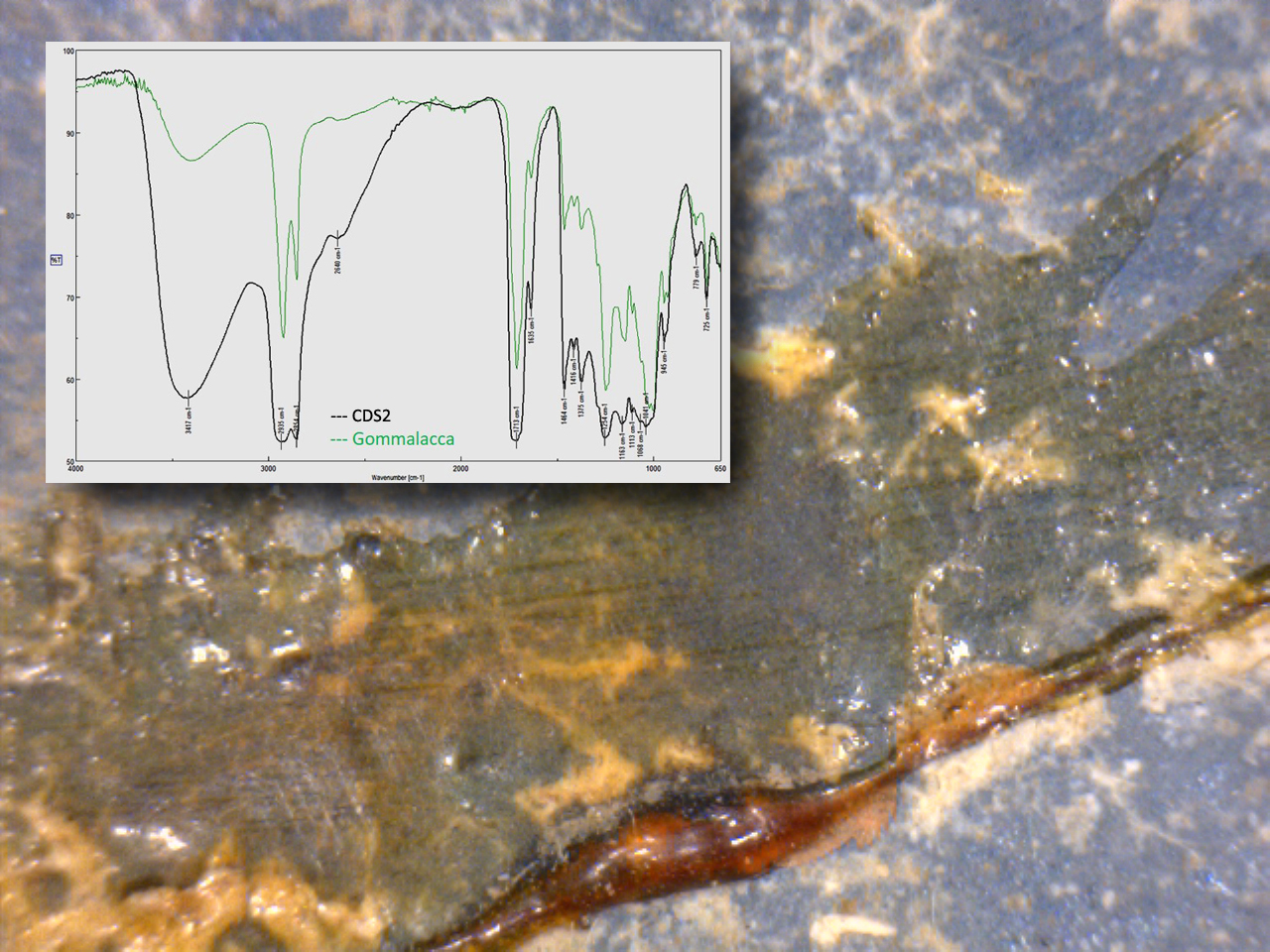

23 | Diffractogram of shellac and macrophoto of gluing with deburring.

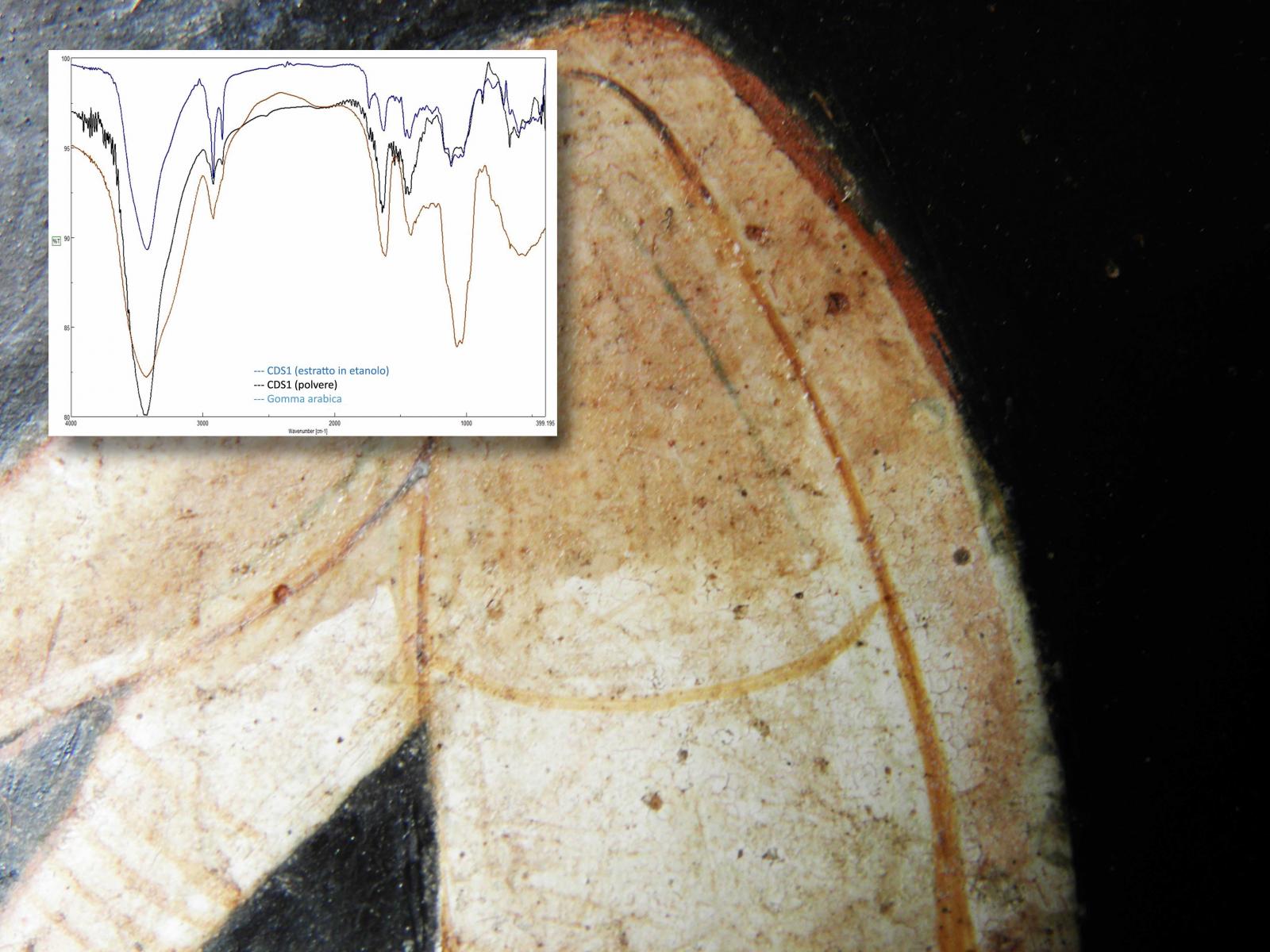

24 | Diffractogram of gum arabic and macrophoto of the removal test.

Only FTIR spectra relating to the organic substances that were found on the liparote masterpiece are disclosed here. Used as adhesive and surface protection they were confirmed as shellac [Fig. 23] and gum arabic [Fig. 24].

Trendall assigned fourteen vases and fragments of varied origins (among those known, Lipari, Syracuse, Gela and Taranto) and from various museums (not exclusively Italian), to the Group Louvre K240 and later, other researchers expanded the Group with new proposals for attribution. It is therefore hoped that this example of Italian-American collaboration in conservation will encourage other museums to submit their archaeological objects for laboratory analysis. Among these artefacts are samples of vases attributed to the Group Louvre K240 workshop as well as to other painters and to other stylistically related proto-Siceliote and proto-Paestan groups that may have operated in the same areas of production.

The key goal of current museum ethical issues cannot be separated from a policy of cultural exchange that aims at seizing opportunities offered by restoration work to deepen the scientific knowledge of works of art themselves while at the same time testing new conservation methods in a constructive sharing of ideas.

Every research project accomplished through the logic of public service should be duly divulged, overcoming prejudices and personalisms, with the aim of promoting greater awareness of cultural heritage in the communities of origin where the objects were found and in those where they are conserved and displayed. The objective is the best preservation of the finds in question, one which ensures “l’accessibilità per motivi di studio delle collezioni, della documentazione e delle conoscenze acquisite, attraverso i mezzi più opportuni per renderne partecipi il più largo numero di persone ad esse interessate” (“the accessibility, for study purposes, of collections, documentation, and knowledge acquired through the most opportune means so as to make participants in these means of the largest number of interested people”: Mibact2000, 34).

“Who Owns Antiquity?” is the question James Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust, has posed in his search for “better ways to protect antiquity”. Our hope is that the response “antiquity knows no border” (Cuno 2010, 146-147) might constitute a real incentive to overcoming barriers of any kind in favor of sustaining a supportive base and unified development amidst three indissolubly interconnected conceptual and operational pillars: new forms of knowledge, preservation and promotion (Murphy 2016)[5].

We thank the Getty Trust of Los Angeles for its kind permission to use the images presented in this paper, with the exception of figs. 4, 7, 19, 20.

Notes

[1] Over one third of the finds on display were borrowed from Sicilian institutions: they notwithstanding later incurred in a 'diplomatic incident' because of the “ensuing controversy, which appeared to cast doubt on the reliability of formal cultural agreements” (Lyons 2014, 255, 259, 262-263 ; Cirino 2013).

[2] The protagonists of these exhibitions were conservation projects on exemplary artefacts, such as the facial reconfiguration of the marble Priapus from the Museo Archeologico Paolo Orsi di Siracusa, the anti-seismic support for the Mothya Youth, the restoration of the Warrior in the severe style (pediment sculpture of Parian marble) from the Archaeological Museum of Agrigento and the green marble pulpit with pre-fabricated architectural elements of a Byzantine basilica from the Marzamemi wreck.

[3] This pioneering initiative involved numerous scholars and practitioners who formed a truly multidisciplinary task force around the krater. The restoration project and the direction of conservation work was taken up by what was then the Archaeological Park of the Aeolian Islands under the supervision of architect Michele Benfari, archaeologist Maria Clara Martinelli, and Dr. Umberto Spigo. As director of the Institute, Dr. Spigo maintained the relationship with the Getty (specifically with Claire Lyons, curator of the exhibition and the Museum's Curator of Antiquities, and with Jerry Podani who, at the time, was Senior Conservator) and proposed the archaeological restoration laboratory of the firm L’ISOLA for the conservation project. L’ISOLA was commissioned by the American museum to carry out the delicate intervention, entirely funded by the Getty. The restoration work, directed and coordinated by architect-conservator Francesco Mannuccia, was carried out in January and February 2013 by Dr. Katia D'Ignoti (art historian and technical director of the pictorial sector of L'ISOLA laboratori di restauro s.r.l.) together with the conservators Corrado Pedelì (Superintendence of Aosta) and Francesca La Sorella (Opificio delle Pietre Dure of Florence). Dr. D'Ignoti, along with Prof. Lorenzo Lazzarini, also presided over the study of manufacturing techniques using non-destructive methods. Laboratory tests were performed by Alberto Convents, Lorenzo Lazzarini and Elena Tesser in the laboratories of the University IUAV Venice, under the direct supervision of Prof. Lazzarini, director of the laboratory. The photogrammetric surveys of the krater with SFM methods were performed by the company Opera s.r.l. from Palermo with the involvement of Prof. Fabrizio Agnello and Arch. Mirco Cannella.

[4] As regards the limits set by non-destructive analysis on the advancement of knowledge, it is not superfluous to emphasize that, with the principle of minimum invasiveness in sampling, the information that can be obtained by non-destructive investigations are, in general, strongly affected by partiality, being related only to the surfaces of materials. Surfaces often exhibit phenomena of chemical alteration (such as elemental enrichment or impoverishment) and/or physical-mechanical modifications that affect obtainable results (Matteini-Moles, 1984, 89-96).

[5] “The recent executive order barring entry into the United States from citizens of seven nations is antithetical to the values of the Getty, and we condemn it in the strongest possible terms”, asserts James Cuno in relation to the ‘travel ban’ of U.S. President Donald Trump (Cuno 2017) attesting to the liberal stance of the California museum on exchange between cultures.

Bibliographical References

- AA. VV. 2016

AA.VV., Sicily and the Sea, Catalogo della mostra all’Ashmolean Museum, Storms, War and Shipwrecks: Treasures from the Sicilian seas, Oxford 2016. - Agnini, Lega

E. Agnini, A. M. Lega, Il restauro della porcellana, Quaderni di restauro della ceramica. Faenza 1999. - Bandini 1992

G. Bandini, Forma e immagine, ossia considerazioni sul problema delle lacune nelle ceramiche, “Faenza” LXXVIII, Fasc. III-IV, (1992), 223-230. - Bernabò Brea, Cavalier 1965

L. Bernabo’ Brea, M. Cavalier, Meligunìs Lipàra II. La necropoli greca e romana della Contrada Diana, Palermo,1965. - Bernabò Brea, Cavalier 1997

L. Bernabò Brea, M. Cavalier, La ceramica figurata della Sicilia e della Magna Grecia nella Lipàra del IV sec. a.C., Milano 1997, 38-46. - Bernabò Brea, Cavalier, Spigo 1994

L. Bernabò Brea, M. Cavalier, U. Spigo, Lipari. Museo Eoliano, Palermo 1994. - Booms, Higgs 2016

D. Booms, P. Higgs, Sicily: Culture and Conquest, Catalogo della mostra al British Museum, London 2016. - Castro, Domenech 1999

E. A. Castro, M. T. Domenech, An Appraisal of the Properties of Adhesives Suitable for the Restoration of Spanish Medieval Ceramics, in N. E. Tennent (ed.), The Conservation of Glass and Ceramics, London 1999, 114-131. - Cirino 2013

G. Cirino, L’antica Sicilia in mostra a Cleveland? A schifìu finìu, “La Voce di New York”, 23 luglio 2013. - Cremonesi 2001

P. Cremonesi, L’uso di tensioattivi e chelanti nella pulitura di opere policrome, Padova 2001. - Cuomo di Caprio [1985] 2007

N. Cuomo Di Caprio, La ceramica in archeologia 2: Antiche tecniche di lavorazione e moderni metodi di indagine, Roma 2007. - Cuno 2010

J. Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity? Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage, Princeton 2010. - Cuno 2017

Statement from James Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust, regarding the travel ban, “news.getty.edu”, 1 February 2017. - Denoyelle, Iozzo 2009

M. Denoyelle, M. Iozzo, La ceramique grecque d’Italie mèridionale et de Sicile. Productions coloniales et apparentèes du VIII au III siecle av. J.C., Paris 2009, 182-183, 238. - Denoyelle 2011

M. Denoyelle, La ceramique grecque de Paestum. La collection du Musèe du Louvre, Paris 2011, 32, 66-76. - Green 2012

J.R. Green, Comic vases in South Italy: Continuity and innovation in the development of a figurative language, in K. Bosher (ed.), Theater Outside Athen, Cambridge 2012, 321-323. - Lazzarini 2000

L. Lazzarini, Primi risultati di uno studio archeometrico di prodotti fittili greci dal ceramico di Scornavacche (Ragusa), in Un ponte fra l’Italia e la Grecia, Atti del Simposio in onore di Antonino Di Vita, Padova 2000, 283-290. - Lyons 2014

C. L. Lyons, Thinking About Antiquities: Museums and Internationalism, “International Journal of Cultural Property” 21 (2014), 251–265. - Lyons, Bennet 2013

C. L. Lyons, M. Bennet, Introduction, in C. L. Lyons, M. Bennet, C. Marconi (eds.), Sicily. Art and Invention between Greece and Rome, Catalogo della mostra al Getty e Princeton, Los Angeles 2013, 1-9. - Matteini-Moles 1984

M. Matteini, A. Moles, Scienza e restauro: metodi di indagine, Firenze 1984. - Mibact 2010

Mibact, Atto di indirizzo del Ministero dei Beni Culturali ed Ambientali sui criteri tecnico scientifici e sugli Standard di funzionamento e sviluppo dei Musei, Linee guida, Roma 2010, 34. - Murphy 2016

B. L. Murphy (ed.), Museums, Ethics and Cultural Heritage, ICOM, London; New York 2016. - Pedelì, Appolonia 1994

C. Pedelì, L. Appolonia, Metodica per uno studio dei materiali da impiegarsi nel trattamento delle lacune formali e pittoriche di ceramiche romane del tipo ‘sigillate’, Faenza LXXX, Fasc. III-IV (1994), 131-171. - Piva 1972

G. Piva, L'arte del Restauro. Il restauro dei dipinti nel sistema antico e moderno secondo le opere di Secco-Suardo e del Prof. R. Mancia, Milano 1972, 181-187. - Pontrandolfo 2000

A. Pontrandolfo, Dioniso e personaggi fliacici nelle immagini pestane, “Ostraka” 9 (2000), 117-134. - Ris Paquot 1876

O. E. Ris Paquot, Manière de restaurer soi-même les faïences, porcelaines, cristaux, Parigi 1876 - Roscino 2012

C. Roscino, Commedia e Farsa in C. Roscino, M. Maggialetti, L. Todisco,VIII. Iconografia e iconologia, in L. Todisco (a cura di), La Ceramica a figure rosse della Magna Grecia e della Sicilia, vol. II, Inquadramento, Roma 2012, 287-295 (in particolare, per il cratere si vedano le pp. 292-293). - Schwarzmaier 2011

A. Schwarzmaier, Die masken aus der Nekropole von Lipari, “Palilia" 21 (2011). - Secco Suardo 1927

G. Secco Suardo, Il Restauratore dei dipinti, Milano 1927, 407-421. - Spigo 2002

U. Spigo, Brevi considerazioni sui caratteri figurativi delle officine di ceramica siceliota della prima metà del iv secolo a.c. e alcuni nuovi dati, in N. Bonacasa, L. Braccesi, E. De Miro (a cura di), La sicilia dei due dionisi, Atti della settimana di studio (Agrigento 24-28 febbraio 1999), Roma 2002, 265-282. - Thiaucourt 1865

P. Thiaucourt, Essai sur l'Art de restaurer les Faïences, Porcelaines, Terres-cuites, Biscuits, Verreries, Emaux, Laques, Marbres, Albâtres, Plâtres, etc., Paris 1865, 9-13. - Trendall 1987

A. D. Trendall, The Red-Figure Vases of Paestum, British School at Rome, Rome 1987, 42-66.

Abstract

Focus of this paper are the complex and multifarious relationships between the Phlyax kalyx-krater with Dionysus and an Acrobat (Lipari, Museo Archeologico Eoliano "L. Bernabò Brea") and its contemporary beholders: a wide range of approaches which span from communication to fruition, from diagnostics to conservation issues, from archaeological to iconographical studies. Aim of the contribution is to provide new insights regarding seminal methods of preservation and to share the knowledge about this masterpiece within the scientific community worldwide, hopefully shedding new light for further research on the so-called “Group of Louvre K420”, a workshop of painters whose production is attested by a large number of vases but still uncertain as its geographical location.

Per citare questo articolo: Dionysus and the Acrobat. Study, Conservation and Promotion of the Lipari Necropolis Kalyx-krater, a cura di L. Lazzarini, F. Mannuccia, U. Spigo, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 148, agosto 2017, pp. 11-29 | PDF dell’articolo

Dioniso e l'acrobata

Studio, conservazione e valorizzazione del cratere a calice della necropoli di Lipari

Lorenzo Lazzarini (Laboratorio di Analisi dei Materiali Antichi, Università IUAV di Venezia)

Francesco Mannuccia (L’ISOLA laboratori di restauro s.r.l.)

Umberto Spigo (già direttore del Parco Archeologico delle Isole Eolie)

Abstract

1 | Claire Lyons, Curator of Antiquities del Getty Museum, osserva il cratere con Dioniso e acrobata proveniente da Lipari.

Dioniso seduto e dinnanzi a lui una acrobata nuda e due attori di commedia. […] Ha una corona di foglie d’edera […] e il lungo tirso che si appoggia alla spalla. La giovane acrobata […] si esibisce in un esercizio tenendosi con le gambe all’insù, e flesse […]. Dei due buffoni che occupano il lato destro della scena, il primo piccolo e tozzo con capelli e barba bianca e con corta exomis […] si curva con le mani sulle ginocchia per ammirare più da vicino le bellezze dell’acrobata […] In alto da due finestrelle appaiono altri due personaggi pronti ad entrare in scena, entrambi con maschera bianca e quindi probabilmente femminili (Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1965, 131).

Così i suoi rinvenitori, Luigi Bernabò Brea e Madeleine Cavalier descrissero, in Meligunis Lipàra II, la scena principale del cratere a calice fliacico – di probabile fabbrica siceliota – che fa parte di un importante gruppo di opere sottoposte a interventi di studio e restauro altamente sofisticati, posti in essere per la loro futura salvaguardia, in occasione della mostra "Sicily. Art and Invention between Greece and Rome" [Figg. 1-2], realizzata per iniziativa del Getty Trust di Los Angeles. Una selezione ragionata di 150 reperti - che, come messo in risalto dai curatori della mostra, “shifts the focus to the Classical and early Hellenistic periods, when Sicilian Greek achievements in art and architecture, poetry and rhetoric, philosophy and history, and mathematics and applied engineering atteined levels of refinement and ingenuity rivaling, even surpassing, those anywhere in Greece” (Lyons, Bennet, 2013, 2-3) - sono stati esposti a Los Angeles ed a Cleveland nel 2013 con il beneplacito dell’Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana [1].

2 | Locandina della mostra tenutasi presso il Getty Villa (Los Angeles) nel 2013.

3 | Visitatori alla mostra del Getty Villa.

Più di 140.000 visitatori hanno svolto un ruolo importante in questo processo di valorizzazione del patrimonio archeologico siciliano [Fig. 3], che ha avuto un seguito nel 2016, con le mostre organizzate al British Museum e all’Ashmolean Museum (Booms, Higgs, 2016; AA.VV., 2016).

I tre eventi – significativi esempi di interazione culturale a livello internazionale – hanno sviluppato programmi di ricerca indirizzati anche ad approfondire la conoscenza delle ‘tecniche artistiche’ e l’incidenza sugli aspetti conservativi dei precedenti restauri cui erano stati sottoposti i singoli capolavori [2]. Progetti di ricerca che, ben al di là della contingenza occasionale, “stimulated a reappraisal of ancient Sicily’s contributions to classical culture” e che “can ramify in unexpected directions” (Lyons 2014, 258, 260) come si chiarirà più avanti.

Il tema della valorizzazione e, attraverso il propedeutico processo diagnostico, quello della conservazione del patrimonio culturale, interagiscono coerentemente con i contenuti e con l’impostazione concettuale di Pots&Plays, uno dei temi di ricerca di "Engramma" e del Centro studi classicA dell’Università Iuav di Venezia. Proprio al cratere liparota, “pezzo di eccezionale interesse per la storia del teatro antico” (Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1997, 40), e alle sue problematiche conservative, è stata dedicata particolare attenzione nel corso del seminario Pots&Plays svolto a Venezia il 16 maggio 2017, che si è delineato quale punto d’incontro tra Iuav e Getty.

4 | Lipari, necropoli di contrada Diana con gli scavi degli anni Cinquanta (da Bernabò Brea, Cavalier 1965, tav. XXXI).

Il cratere venne rinvenuto nell’agosto del 1954 (Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1965, 131) in una tomba a cista in mattoni crudi della necropoli di Lipàra greca nella contrada Diana dell’isola di Lipari dove era utilizzato come cinerario (Tomba 367, scavi a cura della Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Siracusa diretti da Luigi Bernabò Brea e Madaleine Cavalier) [Fig. 4]. La singolarità iconografica della figurazione sul lato principale e la sua straordinaria forza espressiva hanno posto di diritto questo capolavoro – attribuito al Gruppo del Louvre K240 (Trendall 1987, 42-66, n. 91; Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1997, 38-46; Roscino 2012, 287-295) – fra le opere della pittura vascolare dell'Occidente greco maggiormente emblematiche dei legami fra religiosità dionisiaca e universo teatrale (Pontrandolfo 2000; Schwarzmaier 2011).

5 | Esame al videomicroscopio dello stato di conservazione del cratere.

L’esame condotto sul cratere nel 2012, mediante osservazione della sua superficie in videomicroscopia [Fig. 5], allo scopo di valutarne il reale stato di conservazione in vista del viaggio oltreoceano per la mostra in argomento, ha evidenziato la necessità di eseguire un delicato intervento a carattere conservativo che non poteva prescindere dallo smontaggio del reperto stesso.

6 | Schema della proposta del Getty per l’imballo del cratere.

Il rischio di un collasso delle pareti – per quanto protette da un appropriato imballo, appositamente progettato dai tecnici del Getty per il trasferimento dell’opera [Fig. 6] – appariva più che concreto a causa del pessimo stato di conservazione della gommalacca, utilizzata negli anni ’60 del Novecento come collante per l’assemblaggio dei 48 frammenti che compongono il vaso.

Di fronte al comprensibile diniego opposto dal Museo di Lipari alla movimentazione del cratere, viste le precarie condizioni in cui versava, il Paul Getty Museum si è offerto di farsi carico di un radicale intervento conservativo che può definirsi ‘pilota’ per la rilevante ricaduta che ci aspettiamo possa avere sulla conservazione del patrimonio vascolare e coroplastico della Sicilia antica [3].

7 | Antiche 'puntature' in piombo su un cratere attico dalla necropoli di Lipari, Museo Archeologico Regionale “Luigi Bernabò Brea”, sala XXI.

La principale questione conservativa nel nostro caso si è dimostrata quella connessa alla problematica dell’invecchiamento della gommalacca impiegata nei precedenti restauri, che ne comporta la ‘vetrificazione’ e la conseguente perdita di adesività. Fenomeno che interessa purtroppo la maggior parte dei reperti esposti nelle vetrine dei principali musei archeologici siciliani (Siracusa, Palermo, Gela e Lipari), sui quali – alla data della mostra di cui sopra – non si era avviata alcuna sperimentazione per risolvere questa problematica. Occorre sottolineare che questo polimero naturale – il cui impiego nel restauro della ceramica archeologica risale all’Ottocento (Thiaucourt 1865, 9-13) – ebbe ancora a metà del secolo scorso ed oltre una larga diffusione fra i restauratori delle Soprintendenze archeologiche siciliane, come nel caso di Siracusa. Il restauro manutentivo di contenitori fittili è documentato in Sicilia – e non solo – da numerosi esempi dalla tipica pratica della 'puntatura' che consisteva nel realizzare dei fori con un trapano ad archetto, all’interno dei quali venivano poi inserite graffe metalliche o fili che, nei casi più antichi, si presume fossero di materia organica (Ris Paquot 1876) [Fig. 7]. Questo tipo di tecnica è testimoniato a partire dalla preistoria sino al ‘conciabrocche’ Zi’ Dima Licasi di pirandelliana memoria, che fa fatica a far accettare a don Lollò la validità del suo “mastice miracoloso, di cui serbava gelosamente il segreto”.

8 | Micrografie che evidenziano la discontinuità degli incollaggi dei frammenti da cui è stato ricomposto il cratere.

L’esame autoptico, oltre ad avere rilevato la discontinuità degli incollaggi [Fig. 8], mostrava il calice inclinato di alcuni gradi rispetto alla verticale del piede.

9 | Vasca per l’esposizione dei frammenti ai vapori dell’alcool ('sistema Pettenkofer').

10 | Rimozione a bisturi della gommalacca utilizzata nei restauri precedenti, una volta rigonfiata.

Lo smontaggio del vaso secondo un preciso piano di scomposizione della compagine fittile è stato possibile grazie ad un approccio sperimentale che ha fatto ricorso al ‘sistema Pettenkofer’ messo a punto, per tutt’altro scopo, dal chimico tedesco Max Joseph von Pettenkofer a metà Ottocento (Secco Suardo 19274, 407-421; Piva 19722, 181-187). Detto metodo adoperava, infatti, i vapori dell’alcool per ‘ringiovanire’ le vernici alterate e restituire leggibilità ai quadri ad olio: facendo ricorso a tali principi chimico-fisici è stato possibile rigonfiare la gommalacca invecchiata, sino a consentirne la rimozione [Figg. 9, 10].

11 | Frammenti dell’orlo del cratere scomposti.

Coerentemente con la complessa articolazione del quadro fessurativo, è stato necessario mettere a punto una strategia di riassemblaggio che procedesse per sezioni separate [Fig. 11]. Collanti con caratteristiche diverse (Agnini-Lega 1999; Castro-Domenech 1999, 114-131) sono stati impiegati per ricomporre i registri costituenti il cratere, in modo da assicurare appropriate soluzioni per le esigenze specifiche dell’orlo, della parte figurata e del ventre da un lato, e per assicurare il piede dall’altro. Fortunatamente la sezione corrispondente al 'fusto' del vaso era costituita da un unico grande frammento, una sorta di cilindro continuo.

12 | Fase di incollaggio dei frammenti secondo una precisa strategia di riassemblaggio.

Si è così potuto conseguire il perfetto combaciamento dei 48 frammenti [Fig. 12], premessa indispensabile per garantire stabilità strutturale al cratere ricomposto e ripristinare il corretto posizionamento dell’asse verticale di simmetria radiale, deformato dall’attacco del piede al ventre dove i notevoli spessori di gommalacca avevano determinato l’apprezzabile disassamento [Fig. 13].

13 | Scansione 3D (sistema Mephisto).

14 | Pulitura chimica con resine a scambio ionico del grande frammento cilindrico.

L’intervento di pulitura [Fig. 14] è stato condotto sia meccanicamente sia chimicamente, adoperando resine a scambio ionico (Pedelì-Appolonia 1998; Cremonesi 2001), ed è stato volto all’eliminazione e/o all’alleggerimento di tutte quegli elementi di disturbo, quali le incrostazioni di natura carbonatica e la gomma arabica imbrunita, che offuscavano le figurazioni [Fig. 15], le cui cromie sono state saturate dal trattamento di protezione finale.

15 | Il profilo di Dioniso prima e dopo la rimozione delle incrostazioni di natura calcarea e della gomma arabica alterata.

16 | Vista dall’alto del cratere con le stuccature e le riconfigurazioni ben riconoscibili.

Al fine di restituire la continuità materica e l’integrità formale dell’opera, le lacune del corpo ceramico – in più casi passanti – sono state riconfigurate [Fig. 16] realizzando integrazioni e stuccature nel rispetto del principio della riconoscibilità (Bandini 1992, 223-230; Pedelì-Appolonia 1994, 131-17).

Le indagini di laboratorio – propedeutiche in questo caso a individuare la più idonea metodologia di restauro – potrebbero rivelarsi uno stimolante punto di partenza per lo sviluppo di interessanti ipotesi di lavoro interdisciplinare. Analisi archeometriche incrociate di caratterizzazione delle argille di partenza utilizzate per i corpi ceramici e gli ingobbi, nonché dei pigmenti, potrebbero portare nuovi dati sulle aree di produzione e di mercato dei folti gruppi dei ceramografi attivi in età tardo classica fra Sicilia e Italia meridionale tirrenica – in Calabria, Paestum e Campania – oltre che a Locri: i “Sicilian forerrunners” e “the transition from Sicilian to Paestan” secondo le definizioni di Arthur Dale Trendall (Trendall 1987, 22-56; Denoyelle-Iozzo 2009, 166-170,181-183) nel secondo dei quali rientra anche il Gruppo Louvre K240 (Trendall 1987, 42-46; Denoyelle-Iozzo 2009, 181-183; Denoyelle 2012, 32, 66-76).

17 | Il cosiddetto 'Cratere Fleischman' conservato al Getty.

A queste prime analisi stanno, infatti, per aggiungersi quelle che lo stesso committente ha richiesto al LAMA in un ampliamento del progetto che è in corso di definizione, per mettere a confronto il corpo ceramico del nostro con quello del cratere a calice del Museo Getty, attribuito da Trendall allo stesso Gruppo Louvre K240 (Trendall 1987, 46, n.101; Bernabò Brea-Cavalier 1997, 38-46; Roscino 2012, 287-295): il cosiddetto ‘Fleischman proto-Paestan krater’ con scena di danza dionisiaca – alla quale partecipano il dio stesso, in veste di liricine, ed Eros portato a spalla da un sileno auleta – dove il rimando al mondo del teatro è dato dalla presenza di un vecchio phlyax che reca due fiaccole [Fig. 17].

18 | Imballaggio del cratere a Lipari per il trasferimento e l'esposizione presso il Getty nel 2013.

L’importanza dell’intervento di restauro non risiede, quindi, solo nell’aver scongiurato ogni rischio durante la movimentazione del reperto [Fig. 18], e si sminuirebbe l’importanza dell’iniziativa del Getty Museum intendendola semplicemente come finalizzata a ottenere il prestito di un capolavoro la cui assenza avrebbe inficiato le potenzialità attrattive della mostra.

Le sue ricadute positive devono essere invece valutate e lette come ulteriore frutto di quella politica di apertura agli interscambi fra istituzioni, a respiro cosmopolita, da lungo tempo coerentemente portata avanti dal Getty Trust con l’obiettivo di un incremento delle conoscenze coincidente con la valorizzazione dei patrimoni culturali, anche nel quadro di grandi mostre dalle solide basi scientifiche come quella del 2013.

19 | Il cratere eponimo del Gruppo Louvre K240, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Questo intervento conservativo offre l’occasione per analisi comparate, del dato tecnico e stilistico come del patrimonio iconografico e del suo substrato ideologico, con gli altri vasi, non solo a tema fliacico, raggruppati, nell’ambito del Gruppo Louvre K240: dal cratere a campana eponimo, esposto nel museo parigino [Fig. 19] agli altri tre crateri a calice liparesi dai diversi temi dionisiaci (nelle figurazioni di almeno due di essi, dalle tombe 921 e 974, si mostrano evidenti i rimandi al mondo del teatro, pur attraverso indicatori diversi: Fig. 20); dai crateri a calice del Getty Museum (Trendall 1987, 96, n. 101; Green 2012, 322-339, n. 55) a quello di Taranto (Trendall 1987, 46, n. 100); sino al rhyton da Siracusa (Trendall 1987, 47, n. 103).

20 | La vetrina della sala XXI del Museo Archeologico Eoliano "Luigi Bernabò Brea" con i crateri del Gruppo Louvre K240.

21 | Il lato A del cratere con Dioniso e l’acrobata con la scena principale.

Infatti il ritorno ad una leggibilità dei valori disegnativi e cromatici certamente più vicina agli esiti originari assolve a nostro avviso anche un’efficace funzione di medium verso il più compiuto apprezzamento dell’impianto espressivo della scena sul lato principale – la cui pregnanza non è disgiungibile dalla perizia tecnica del ceramografo – imperniato sulla interazione fra gli elementi descrittivi mutuati dalla realtà teatrale e la componente metaforica, legati alla centralità di Dioniso e del suo polivalente universo cultuale [Fig. 21]. Viene così data forza a letture interpretative quali quella di J. Richard Green che ha efficacemente colto il key point della figurazione “in the ambiguity between the actuality of performance and the further reality involving the god’s presence” (Green 2012, 321-323).

Ma una più circostanziata messa a fuoco del ruolo di questo Gruppo nella diffusione di soluzioni iconografiche e di accenti stilistici in area tirrenica – nello specifico circa la reale configurazione dei rapporti con le prime fasi produttive delle officine di Paestum, in particolare nell’opera di Assteas – richiede una più ampia integrazione conoscitiva dei dati di contesto (sia grazie ad auspicabili nuove acquisizioni di scavo, sia attraverso la revisione di vecchi rinvenimenti) per l’inquadramento cronologico: al momento le associazioni con le forme della ceramica a vernice nera presente nei quattro corredi tombali liparesi condurrebbero già all’inizio del secondo quarto del secolo, discostandosi quindi dalla datazione almeno di un decennio più alta (390-380 a.C.) proposta da Martine Denoyelle (Denoyelle 2011, 32, 66-76).

Allo stesso modo rimane ancora del tutto aperta l’individuazione del centro o forse dei centri di produzione, per la quale – in virtù delle indubbie proiezione ‘tirreniche’ fra Paestum e Campania – si era a suo tempo proposta una localizzazione fra l’area dello Stretto di Messina (preferibilmente la sponda siciliana) e Lipari, plausibile ma tutt’ora non sostenuta da dati scientificamente probanti (Spigo 2002, 277).

Allo sviluppo di questo tema potrebbero portare le indagini archeometriche incrociate, delle quali si è già fatta menzione.

Approfittando del fatto che nel corso dello scollamento dei pezzi del vaso una scaglietta del corpo ceramico si separò spontaneamente, risultando non ricollocabile, venne su di essa eseguita una serie di analisi di laboratorio secondo una sequenza programmata in modo da ottenere il massimo di informazioni sui materiali costituenti e sulla sua tecnica di esecuzione (Cuomo di Caprio [1985] 2007; Lazzarini 2000, 283-290) [4].

22 | Sala del microscopio elettronico presso il laboratorio LAMA dell'Università Iuav di Venezia.

Una porzione della scaglietta è stata dunque polverizzata in mortaio di agata e sottoposta ad analisi diffrattometrica (XRD). I residui di colla ad essa aderenti sono stati rimossi con un bisturi e sottoposti a un esame in spettroscopia all'infrarosso con trasformata di Fourier (FTIR) [Fig. 22]. Il resto della scaglietta è stato quindi utilizzato per la preparazione di una sezione lucida, previo inglobamento in una resina poliestere polimerizzabile a freddo, di seguito sottoposta ad analisi chimica quantitativa, mediante microscopia elettronica a scansione accoppiata a spettrometria a dispersione di energia (SEM+EDS). Infine, dalla sezione lucida si è allestita una sezione sottile standard, poi studiata petrograficamente al microscopio ottico polarizzatore. I risultati di tutte queste analisi verranno pubblicati in altra sede, congiuntamente a quelli ottenuti da analoghe metodologie sul campione di corpo ceramico dal citato ‘Fleischmann proto-Paestan krater’ inviato al LAMA dal Getty nel contesto del nuovo progetto avviato con il museo americano.

23 | Diffrattogramma della gommalacca e macrofoto di un incollaggio che evidenzia la sbavatura.

24 | Diffrattogramma della gomma arabica e macrofoto del test di rimozione.

In questa sede vengono resi noti esclusivamente gli spettri FTIR relativi alle sostanze organiche riscontrate sul cratere liparota dove sono impiegate come collante e/o protettivo e risultate essere gommalacca [Fig. 23] e gomma arabica [Fig. 24].

Considerando che Trendall ha assegnato al Gruppo Louvre K240 quattordici fra vasi e frammenti di varie provenienze (fra quelle note: Lipari, Siracusa, Gela e Taranto), distribuiti in più musei (non solo italiani) e che, successivamente, altri studiosi hanno incrementato il Gruppo con nuove proposte di attribuzione, si spera che questo esempio di collaborazione italo-americana porti altre istituzioni museali a sottoporre ad analisi di laboratorio campioni di vasi attribuiti a questa officina oltre che a ulteriori pittori e gruppi protosicelioti e protopestani stilisticamente collegati che possono aver operato anche negli stessi ambiti produttivi.

Il key goal dell’etica del museo attuale non può prescindere dalla politica di scambi culturali finalizzati, fra l’altro, a cogliere le occasioni offerte dagli interventi di restauro per approfondire la conoscenza scientifica delle stesse opere d'arte, e sperimentare nuove metodologie conservative in un costruttivo confronto d’idee.

Ogni ricerca, essendo compiuta nella logica del pubblico servizio, andrebbe doverosamente divulgata, superando pregiudizi e personalismi, per promuovere la più ampia consapevolezza del patrimonio culturale nelle comunità di pertinenza e la miglior conservazione delle raccolte, assicurando “l’accessibilità per motivi di studio delle collezioni, della documentazione e delle conoscenze acquisite, attraverso i mezzi più opportuni per renderne partecipi il più largo numero di persone ad esse interessate” (Mibact 2000, 34).

“Who owns antiquity?” si chiede James Cuno – presidente del J. Paul Getty Trust – nel suo cercare “better ways to protect antiquity”. Il nostro auspicio è che la risposta “antiquity knows no border” (Cuno 2010, 146-147) possa costituire un reale incentivo al superamento delle barriere di qualsiasi genere a favore del radicamento e dello sviluppo unitario dei tre grandi capisaldi concettuali e operativi indissolubilmente interconnessi: nuove forme di conoscenza, tutela e valorizzazione [5].

Si ringrazia il Getty Trust di Los Angeles per la gentile concessione delle immagini presentate in questo contributo, con l'eccezione delle Figg. 4, 7, 19, 20.

NOTE

[1] Oltre un terzo dei reperti in mostra è stato concesso in prestito da istituzioni siciliane, salvo poi incorrere in un ‘caso diplomatico’ a motivo della “ensuing controversy, which appeared to cast doubt on the reliability of formal cultural agreements” (Lyons 2014, 255, 259, 262-263; Cirino 2013).

[2] Protagonisti di queste esposizioni sono stati gli interventi conservativi su manufatti esemplari, quali la riconfigurazione facciale del Priapo in marmo del Museo Paolo Orsi, il supporto antisismico per il Giovinetto di Mothya, il restauro del Guerriero in stile severo (scultura frontonale in marmo pario) del Museo di Agrigento e dell’ambone in marmo verde della Tessaglia dal relitto di Marzamemi con gli elementi architettonici prefabbricati di una basilica bizantina.

[3] Questa pioneristica iniziativa ha visto coinvolti numerosi studiosi e operatori, che intorno al vaso hanno costituito una vera e propria task force multidisciplinare. Il progetto di restauro e la direzione dei lavori dell’intervento sono stati curati dall’allora Parco Archeologico delle Isole Eolie nelle persone dell’architetto Michele Benfari, della dott.ssa Maria Clara Martinelli e del dr. Umberto Spigo, che, in qualità di direttore dell’Istituto ha anche tenuto i rapporti con il Getty (nello specifico con Claire Lyons, la curatrice della mostra e Curator of Antiquities del museo, e con Jerry Podani, a quella data Senior Conservator) segnalando il laboratorio di restauro archeologico della ditta L’ISOLA, incaricata dal museo americano del delicato intervento conservativo, interamente finanziato dallo stesso Getty. Il restauro, diretto e coordinato dall’architetto-restauratore Francesco Mannuccia, è stato eseguito nei mesi di gennaio e febbraio del 2013 dalla dott.ssa Katia D’Ignoti (storica dell’arte e direttore tecnico del settore pittorico de L’ISOLA laboratori di restauro s.r.l.) unitamente ai restauratori Corrado Pedelì (Soprintendenza di Aosta) e Francesca La Sorella (Opificio della Pietre Dure di Firenze). La dott.ssa D’Ignoti ha anche curato lo studio delle tecniche esecutive con metodiche non distruttive, insieme al prof. Lorenzo Lazzarini. Le indagini di laboratorio sono state eseguite da Alberto Conventi, Lorenzo Lazzarini ed Elena Tesser nei laboratori dell’Università Iuav di Venezia, sotto la diretta supervisione dello stesso Lazzarini, direttore del laboratorio. I rilievi fotogrammetrici del cratere con metodi SFM sono stati eseguiti dalla società Opera s.r.l. di Palermo e segnatamente dal prof. Fabrizio Agnello e dall’arch. Mirco Cannella.

[4] Circa i limiti posti dalle analisi non distruttive all’avanzamento delle conoscenze, non sarà superfluo sottolineare che, fermo restando il principio della minor invasività dei prelievi, le informazioni che si possono ricavare dalle sole indagini non distruttive sono in generale fortemente condizionate da parzialità essendo relative soltanto alle superfici dei materiali, superfici che spesso presentano fenomeni di alterazione chimica (come ad esempio arricchimenti o impoverimenti elementali) e/o di modificazioni fisico-meccaniche tali da condizionare i risultati ottenibili (Matteini-Moles 1984, 89-96).

[5] “The recent executive order barring entry into the United States from citizens of seven nations is antithetical to the values of the Getty, and we condemn it in the strongest possible terms”, dichiara James Cuno relativamente al ‘travel ban’ di Donald Trump (Cuno 2017), testimoniando la liberalità del museo californiano negli scambi tra culture.

Riferimenti bibliografici

- AA. VV. 2016

AA.VV., Sicily and the Sea, Catalogo della mostra all’Ashmolean Museum, Storms, War and Shipwrecks: Treasures from the Sicilian seas, Oxford 2016. - Agnini, Lega

E. Agnini, A. M. Lega, Il restauro della porcellana, Quaderni di restauro della ceramica. Faenza 1999. - Bandini 1992

G. Bandini, Forma e immagine, ossia considerazioni sul problema delle lacune nelle ceramiche, “Faenza” LXXVIII, Fasc. III-IV, (1992), 223-230. - Bernabò Brea, Cavalier 1965

L. Bernabo’ Brea, M. Cavalier, Meligunìs Lipàra II. La necropoli greca e romana della Contrada Diana, Palermo,1965. - Bernabò Brea, Cavalier 1997

L. Bernabò Brea, M. Cavalier, La ceramica figurata della Sicilia e della Magna Grecia nella Lipàra del IV sec. a.C., Milano 1997, 38-46. - Bernabò Brea, Cavalier, Spigo 1994

L. Bernabò Brea, M. Cavalier, U. Spigo, Lipari. Museo Eoliano, Palermo 1994. - Booms, Higgs 2016

D. Booms, P. Higgs, Sicily: Culture and Conquest, Catalogo della mostra al British Museum, London 2016. - Castro, Domenech 1999

E. A. Castro, M. T. Domenech, An Appraisal of the Properties of Adhesives Suitable for the Restoration of Spanish Medieval Ceramics, in N. E. Tennent (ed.), The Conservation of Glass and Ceramics, London 1999, 114-131. - Cirino 2013

G. Cirino, L’antica Sicilia in mostra a Cleveland? A schifìu finìu, “La Voce di New York”, 23 luglio 2013. - Cremonesi 2001

P. Cremonesi, L’uso di tensioattivi e chelanti nella pulitura di opere policrome, Padova 2001. - Cuomo di Caprio [1985] 2007

N. Cuomo Di Caprio, La ceramica in archeologia 2: Antiche tecniche di lavorazione e moderni metodi di indagine, Roma 2007. - Cuno 2010

J. Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity? Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage, Princeton 2010. - Cuno 2017

Statement from James Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust, regarding the travel ban, “news.getty.edu”, 1 February 2017. - Denoyelle, Iozzo 2009

M. Denoyelle, M. Iozzo, La ceramique grecque d’Italie mèridionale et de Sicile. Productions coloniales et apparentèes du VIII au III siecle av. J.C., Paris 2009, 182-183, 238. - Denoyelle 2011

M. Denoyelle, La ceramique grecque de Paestum. La collection du Musèe du Louvre, Paris 2011, 32, 66-76. - Green 2012

J.R. Green, Comic vases in South Italy: Continuity and innovation in the development of a figurative language, in K. Bosher (ed.), Theater Outside Athen, Cambridge 2012, 321-323. - Lazzarini 2000

L. Lazzarini, Primi risultati di uno studio archeometrico di prodotti fittili greci dal ceramico di Scornavacche (Ragusa), in Un ponte fra l’Italia e la Grecia, Atti del Simposio in onore di Antonino Di Vita, Padova 2000, 283-290. - Lyons 2014

C. L. Lyons, Thinking About Antiquities: Museums and Internationalism, “International Journal of Cultural Property” 21 (2014), 251–265. - Lyons, Bennet 2013

C. L. Lyons, M. Bennet, Introduction, in C. L. Lyons, M. Bennet, C. Marconi (eds.), Sicily. Art and Invention between Greece and Rome, Catalogo della mostra al Getty e Princeton, Los Angeles 2013, 1-9. - Matteini, Moles 1984

M. Matteini, A. Moles, Scienza e restauro: metodi di indagine, Firenze 1984. - Mibact 2010

Mibact, Atto di indirizzo del Ministero dei Beni Culturali ed Ambientali sui criteri tecnico scientifici e sugli Standard di funzionamento e sviluppo dei Musei, Linee guida, Roma 2010, 34. - Murphy 2016

B. L. Murphy (ed.), Museums, Ethics and Cultural Heritage, ICOM, London; New York 2016. - Pedelì, Appolonia 1994

C. Pedelì, L. Appolonia, Metodica per uno studio dei materiali da impiegarsi nel trattamento delle lacune formali e pittoriche di ceramiche romane del tipo ‘sigillate’, Faenza LXXX, Fasc. III-IV (1994), 131-171. - Piva 1972

G. Piva, L'arte del Restauro. Il restauro dei dipinti nel sistema antico e moderno secondo le opere di Secco-Suardo e del Prof. R. Mancia, Milano 1972, 181-187. - Pontrandolfo 2000

A. Pontrandolfo, Dioniso e personaggi fliacici nelle immagini pestane, “Ostraka” 9 (2000), 117-134. - Ris Paquot 1876

O. E. Ris Paquot, Manière de restaurer soi-même les faïences, porcelaines, cristaux, Parigi 1876 - Roscino 2012

C. Roscino, Commedia e Farsa in C. Roscino, M. Maggialetti, L. Todisco,VIII. Iconografia e iconologia, in L. Todisco (a cura di), La Ceramica a figure rosse della Magna Grecia e della Sicilia, vol. II, Inquadramento, Roma 2012, 287-295 (in particolare, per il cratere si vedano le pp. 292-293). - Schwarzmaier 2011

A. Schwarzmaier, Die masken aus der Nekropole von Lipari, “Palilia" 21 (2011). - Secco Suardo 1927

G. Secco Suardo, Il Restauratore dei dipinti, Milano 1927, 407-421. - Spigo 2002

U. Spigo, Brevi considerazioni sui caratteri figurativi delle officine di ceramica siceliota della prima metà del iv secolo a.c. e alcuni nuovi dati, in N. Bonacasa, L. Braccesi, E. De Miro (a cura di), La sicilia dei due dionisi, Atti della settimana di studio (Agrigento 24-28 febbraio 1999), Roma 2002, 265-282. - Thiaucourt 1865

P. Thiaucourt, Essai sur l'Art de restaurer les Faïences, Porcelaines, Terres-cuites, Biscuits, Verreries, Emaux, Laques, Marbres, Albâtres, Plâtres, etc., Paris 1865, 9-13. - Trendall 1987

A. D. Trendall, The Red-Figure Vases of Paestum, British School at Rome, Rome 1987, 42-66.

Abstract

Il saggio affronta i diversi risvolti che il cratere fliacico con Dioniso e l'acrobata del Museo Archeologico Eoliano incontra nel suo interfacciarsi con la contemporaneità: dalla comunicazione alla fruizione, dalla diagnostica alla conservazione, dallo studio della tecnica ceramografa a quello della iconografia teatrale. Si vuole offrire un contributo alla crescita delle conoscenze e alla loro condivisione, foriero di approfondimenti che potrebbero restituire identità al nutrito repertorio vascolare attribuito al così detto ‘gruppo del pittore di Louvre K240’, la cui bottega non ha ancora sicura collocazione geografica.

keywords | Dionysus; Archeology; Iconography; Conservation Methods; Museo Archeologico Lipari

Per citare questo articolo: Dioniso e l'acrobata. Studio, conservazione e valorizzazione del cratere a calice della necropoli di Lipari, a cura di L. Lazzarini, F. Mannuccia, U. Spigo, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 148, agosto 2017, pp. 31-48 | PDF dell’articolo