From cuts to clues, hidden narratives within the details of Carl Durheim’s photographic portraits

Sara Romani*

English abstract

Carl Durheim was a lithographer and photographer from Bern (1810-1890). The Swiss draftsman successfully introduced the photographic technology within his business activity in Bern after receiving an education as typographer and lithographer in Paris. During his years of itinerancy between France, Belgium and Italy (1827-1841) Durheim encountered several enthusiasts engaged with the photographic process: he witnessed unsuccessful attempts to fix the latent image on paper in Turin in 1839, as well as early Daguerreotypes in Paris in 1841; despite the general euphoria for the French ‘invention’, he hesitated to learn the process and only later, in 1845, he foresaw a business opportunity for his already on-going lithographic atelier in Bern, soon advertising himself as Daguerreotypist after few months of practice [1]. His activity as portraitist includes an extensive production of portraits on metal plate for the Bernese bourgeoisie, as well as colourful portraits on salt paper and later on in the format of the carte-de-visite. With careful attention to the taste of his clients and the trends imported from abroad, Durheim soon learned the calotype process in Frankfurt am Main (1849) and started to collaborate with skilful painters in order to have his salt prints coloured [2].

In addition to the ‘celebrative pictures’ of the local middle-class, Durheim’s portraiture production includes an anthology of about 228 salt prints collected at the Swiss Federal Archive in Bern. Located at the opposite end of the social spectrum, these pictures portray a group of Swiss itinerants without citizenship (Gasser-Meier-Wolfensberger 1998). The existing scholarship on Durheim has devoted far less attention to his working practice and his network of collaborations as a draftsman than to his ability as a businessman and image-maker. This can certainly be attributed to the fact that no document has yet been found in which Durheim himself expresses his personal opinion about the conception of his work aside from his autobiographies, where photography is described as a lucrative commercial activity suitable for the sustainment of his family. Historians have yet to find contracts or correspondence that document Durheim’s working relations with painters or amateurs who helped him deliver his photographic products; nonetheless Durheim was very good at advertising his activity on newspapers and he never failed to leave his trademark behind his photographs.

The following contribution sets out to start filling this gap: as I will show in what follows, unnoticed details of Durheim’s pictures reveal modes of production and working practices that document the earliest confrontations with the varieties of photography’s reception and the entanglement of working practices among amateurs, painters, draftsmen and photographers of mid 19th century Switzerland. The analysis of the pictures produced by commercial photographers provides the basic discourse of a system of values: it allows to identify habits, behaviors and implicit systems of relationships and working practices handed down over time. Such a history of photography exists as a “anthropological text” that asks the historian to be read in the details of representations and media relations (Miraglia 2011, 135).

As a case study, I will focus on two reproductions of Durheim’s pictures as examples used in the literature on the early history of photography in Switzerland. I will indicate where a physical or metaphorical cut has been carried out on Durheim’s pictures and starting from there I will investigate the kind of information that has been cut out, in order to investigate hidden narratives on photography and its early history. Rather than describing Carl Durheim’s activity from the standpoint of his art, perpetuating a historiographical approach that privileges “conventional hierarchies of photographic value” (Caraffa 2019, 11), the present paper focuses on the reception of the photographic processes and the photographer’s working network, where parallel practices of printmaking, painting and photography interweave. In this sense Durheim’s work is considered within a network of professionals and amateurs, who collaborated in the early industrial age, where “far from being rivals and mutually exclusive, photography on paper and photography on metal were two parallel arts destined to support each other” (Roubert 2018, 31), and “underlying the connections between printmaking, painting and photography […] is the 19th century practice of reproduction” (Bann 2011, 14). I indicate as ‘clues’ precisely what has hitherto been cut out of the discourse. As the title suggests, I start from identifying cuts in order to use them as clues that reveal embedded or hidden narratives.

The first meaning of cut is thus intended as the physical edge of an image, which surrounds and defines the framing; the second meaning regards the metaphorical cut, intended as the selection of those details that has been more or less deliberately omitted from the narrative. In this way I investigate how such physical cuts are subject to or depend on the text that flanks the image, i.e., I ask how far these physical cuts reflect the narrative’s intellectual framings. My aim is to align a study on Carl Durheim’s portraiture production with already existing research on the “archaeology of actors and uses”, and to bring to light photography “as the fruit of a social, political and aesthetic situation; at the same time a method, a fashion, an experiment, a stage” (Aubernas Roubert 2010, 16).

“… probably she had been photographed here for the first time”

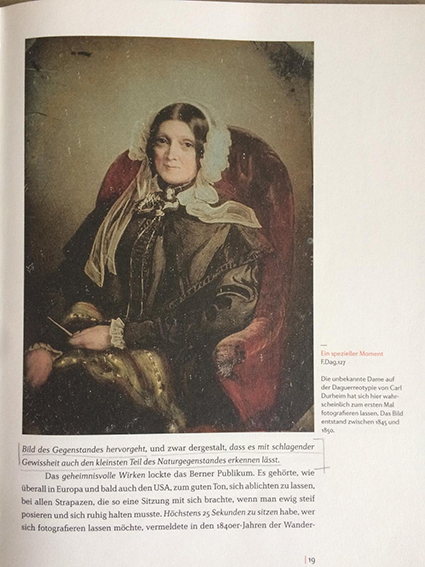

1| Carl Durheim, “Wie die Fotografie nach Bern kam”, Catalogue Burgerbibliothek Bern, p. 19.

The unknown woman on the Daguerreotype by Carl Durheim probably had been photographed here for the first time. The picture was taken between 1845 and 1850 (Giger 2016, 19).

This caption labels a reproduction of a metal plate by Carl Daurheim housed at the Burgerbibliothek in Bern, which appears in the publication Carl Durheim, Wie die Fotografie nach Bern kam.

On a full page Durheim’s image stands out: a red armchair frames the thin figure of an elegant old lady dressed in black with a white bonnet, sitting quietly, whit her hands on her lap. The lady looks toward the viewer in a traditional three-quarter pose, as if she was asked to pause for a moment from her occupation (probably knitting) and to hold still [Fig. 1]. From the information provided by both the image and the caption at the bottom of the page, one can imagine what happened in Durheim’s atelier: the lady arrived in the photographer’s studio, where she was asked to sit down in the red armchair. One sees the photographer adjusting the light and the camera in his glass atelier, handling carefully the chassis with the prepared plate; then, after reminding the lady to hold still, in a few seconds of exposure the picture was finally taken. The photographer would then have developed the positive and worked on the fine coloring following the taste of the client.

I was surprised when I visited the Burgerbibliothek in Bern and two daguerreotypes depicting the lady were handed to me [Fig. 2-3]. The two Daguerreotypes are identical in terms of subject and coloring, the only substantial difference regards the shape of the frame, which in one case is oval and the other is rectangular. Another difference lies in the state of conservation. For the small dimension and the play of reflections that characterize each Daguerreotype, the difficulty of seeing the actual portrait was another aspect, which immediately surprised me. Certainly, the illustration on the aforementioned publication favored an immediate reading of the image (it is reproduced as a 12x16,4 cm image versus a 10,5x 7cm metal plate), which the archival object at first sight does not allow. But the real surprise came when, thanks to the magnifying glass, I could notice that there was a detail within the picture that I missed while looking at its reproduction. The detail consists of a signature and a date on the left side that I could barely read. The signature and date, mirrored, read: “Dietler, 1849”.

2-3| Carl Durheim, “Daguerreotype”, painted, Burgerbibliothek Bern, F.Dag.133, F.Dag.127. Photo: Jürg Bernhardt.

The amount of details that I encountered while looking at the archival objects (i.e. the signature and the date, two metal plates, the size…) stood out as anomalies in comparison to the clarity and accessibility of the reproduction; such anomalies challenged my initial reading of the photographic object as I saw it reproduced in the book. Most of all, the information acquired at the archive could not but clash with the information provided in the caption, which suggested that the lady’s identity was unknown and that she was sitting in front of the camera probably for the first time. After recognizing the signature I started to formulate a different narrative about the situation behind the picture’s production: the photographic portrait was actually the reproduction of a painting made by a famous local painter: Johann Friedrich Dietler (1804-1874). This of course means also that the lady was not portrayed by the photographer first, but rather by the painter, and the photographer reproduced the painting through the process of Daguerre. Johann Friedrich Dietler was a leading portraitist in Bern and worked assiduously for the Bernese patrician families. The painter was at his best in watercolors portraits and literature on Dietler estimates that he had created over 5000 portraits during his almost 40 years of activity in Bern (Gropp 2018, 47). In the online archive catalogue of the Burgerbibliothek Bern, 376 records have so far been linked with the personal descriptor “Dietler, Johann Friedrich Dietler”.

In order to be sure that the original subject that once sat in front of the camera was not a lady but a painting, I looked for the original painting in the online catalogue of the Burgerbibliothek, and I found was – unfortunately not the original, but rather two black and white reproductions of a couple of different paintings depicting the aforementioned lady.

4| Johann Friedrich Dietler, Aquarell, 1849, Burgergbibliothek Bern, Porträtdok. 5056

Only one of them, however, is the painting that Durheim reproduced: the two daguerreotypes are obviously mirrored with respect to the painting, so that the signature and the date appear on the right side in only one of the two, and it is found, on the contrary, on the right side in the other [Fig. 4].

The painting reproduced by Durheim portrays Constance Helene Katharina von Sinner (1805-1849), it is a watercolor on paper and measures 21x16 cm. The recognition of the signature and date on the Daguerreotype, has made it possible to gather more information on the archival object per se. In fact, since Durheim’s Daguerreotypes do not have a date of production, one can now reasonably conjecture that Durheim took the picture either the same year the painter finished the portrait (1849), or later. The lady is not unknown, but she is, again, Constance Helene Katharina von Sinner, who died in 1849, the year when the painting was commissioned, and probably when the Daguerreotypes, too, were taken. Generally speaking, reproducing a portrait of a loved one by photography after his or her death was a common practice: interestingly, according to Burgdorf art historian Dr. Alfred Guido Roth (1913-2007), Durheim was probably commissioned to reproduced another portrait by Dietler around 1852: the Museum Schlossburgdorf possesses a Daguerreotype by Carl Durheim depicting Victoire Schnell. The Daguerreotype plate is unfortunately in very bad conditions, but according to Alfred Guido Roth it may have been painted by Joh. Friedrich Dietler (1804-1874), who at that time also carried out commissions for the Schnell family [3]. The scant documentation only allows to formulate hypotheses, but further reflections on the nature of the archival object and the methodological approach to write about its history can be advanced. The fact that the painting was reproduced on the metal plate influences the reading of the portrait as image, which serves evidently different social needs.

The preciousness and precision of the Daguerreotype, and yet its difficult reading, turns the woman’s portrait from an accessible visual representation to a three-dimensional object; while the painting traditionally answers the quest for resemblance and respectability first, the Daguerreotype adds to this meaning the quality proper to a precious object, through its being delicate and at the same time transportable. One can conjecture that, if the Daguerreotype was commissioned after the lady's death – as it seems reasonable to believe – the photographic plate performed a commemorative function in addition to the celebratory function already performed by the pictorial portrait.

The detail of the signature and date was – metaphorically speaking – cut out from the initial illustration in the book and, as a consequence, the brief explanation of the caption missed the nature of the archival object and its implications in serving different social uses. I demonstrated how the acknowledgment of the detail could conversely reveal to be a clue that calls for a different narrative: details disclose the possibility of new narratives, in that they reveal previously unnoticed layers of reading. On the level of a renovated study on Carl Durheim’s portrait production of the standpoint of the reception of photography and its relation with the practice of reproduction, the acknowledgement of the painting behind the daguerreotype has transformed “the object of research” (Caraffa 2011, 11): similarly to what happened with the introduction of documentary photography, the object of research – the painting and the Daguerreotype – “were detached from their original surrounding, converted into standardized and transportable formats, newly contextualized and made comparable” (Caraffa 2019, 17) thanks to both the illustration in the book and the digital database of the archive. In Durheim’s case, the transformation takes place on two levels: the first transformation regards the use and function of the photographic object at the time of its creation. The painting intended for its representational quality as portrait, as image, was transformed firstly at the level of its being an object. Thanks to the Daguerreotype, the painting was converted into a transportable object. The visibility of the image has also changed: the case containing the plate was thought for a private gaze and in order to look at the portrait reproduced on the metal plate one should turn it back and forth until a light gray image appeared. The painting, although probably exposed in a space of private property was available for every gaze entering the room.

The second transformation regards the present ‘use’ of the photographic object, and its epistemological potential as research object (Caraffa 2011, 11). From the standpoint of the historical research on Carl Durheim’s portraiture production, the acknowledgment of the nature of the depicted object, i.e., the acknowledgement of the painting as the object photographed on the Daguerreotype plate, redirects the investigation on Durheim’s work. Such turn – the interest for the use of photography and the practice of reproduction – introduces a further and wider topic of inquiry, which is the 19th century practice of reproduction in Switzerland in the context of the working relationship among famous painters, minor draftsmen (such as lithographers, miniaturists…) and commercial photographers. Thanks to the information gathered with the analysis of the metal plate, I inevitably began to wonder if Durheim and Dietler had any business relations. My question is justified by a series of ads published by Durheim, to which I will refer in the second part of the article. “Will not captions become the essential component of pictures?” Walter Benjamin prophesized (Benjamin, 1931, 23). I suggest that captions become the essential components of pictures when, as Durheim’s example shows, it comes to writing the genesis and history of the archival object and its relation to other archival pieces. The topic cannot be exhausted in this article; however, the general lines of the debate on the historiography of the history of photography can be outlined.

The average dimension of a historical phenomenon

“It is necessary to start from seemingly marginal details in order to grasp the general reality darkened by the fog of ideology” (Ginzburg 2016, 6) stated the historian Carlo Ginzburg in an essay on the “Conjectural Paradigm” and his reflections on it twenty-five years later. It is possible to consider a series of clues as one piece of evidence: the historian challenged what he identified as “the evidential paradigm”, a cross-disciplinary method of inquiry that interests history as discipline, which grants knowledge because of the direct links between observation of specific data used to draw a general (universal) conclusion. The historian suggests, on the contrary, to consider anomalies within a series as clues that “indicate or signal” embedded narratives, instead of demonstrating through major pieces of evidence the general trend or the average dimensions of a historical phenomenon. A renovated look at the relation among painters, printmakers and photographers requires a reflection on the historiographical approach adopted in the investigation of early Swiss photography and its implication in the formation of photography’s identity in the art-historical texts. The art historian Martin Gasser has already showed how, in the near France, “photography’s path originated in the context of industrie” and how the contemporaneous debate “shifted from the making to the maker of photographs giving rise to the emergence of the photographer as artist” (Gasser 1990, 8-29). In a different article Gasser also shows how in the German-speaking countries and in the early writings on photography’s origin, “the intense illumination of the nationalistic undertones have directed the priority towards the claim for local inventors and contributors” (Gasser 1992, 50-60). These two positions described by Martin Gasser can be found in the first text written about Carl Durheim’s photographic activity. Erich Stenger dedicated in 1940 a chapter to the Bernese pioneer Carl Durheim, titled Der Beruf wird Bodenstaendig 1845-1862. The contribution belongs to the first historical survey on the early history of photography in Switzerland, namely Die Beginnende Fotografie im Spiegel von Tageszeitungen und Tagebuecher, which became the bedrock literature for those historians interested in the historical survey on Durheim’s work as commercial photographer. Erich Stenger writes:

Noch im Jahre 1852 bezeichnete sich Durheim in senen Zeitungsanzeigen als Lithograph, im folgenden Jahre kann man beobachten, wie die Photographie die Überhand in Durheims Tätigkeit gewinnt; nachdem er sich noch einige Zeit Lithograph und Photograph gennat hatte, tritt er gegen Ende des Jahres meist nur noch als Photograph an die Öffentlichkeit. Beachtlich ist, daß auch Durheim, wie so viele der Frühzeit und meist gerade die Besten, aus der handwerklichen Kunst zur Photographie gelangte.

[Still in 1852 Durheim identified himself in his advertisements as Lithographer, in the following years it is possible to observe how photography stood out in his activity; after little time he still identified himself as both lithographer and photographer, by the end of the years (1850s) he introduced himself to the public only as photographer. It is remarkable that Durheim, too, like the majority at the beginning and the majority of the best (practitioners), arrived to photography from the arts.] (Stenger 1940, 60-61)

As the title suggests, the German historian carefully analyzed local newspapers in order to reconstruct Durheim’s carrier and locate in the linguistic register of the traditional media – such as painting – the reception of photography (Wolf, 2018). Stephen Bann defines such approach as “an historiographical form of a pattern of progress and fulfillment” (Bann 2001, 16), by recalling the reading of the history of the image from Hayden White to Erich Auerbach. With such interpretative framework in mind, Durheim’s implication with photography has been described following the “average dimension of the historical phenomenon” (Ginzburg 2016, 6); following Stenger’s thought, Durheim belongs to those groups of artisans, who became portrait photographers because they couldn’t help profiting from of the photographic technology as a business activity. This reading goes hand in hand with the logic of progress, which considers the history of the technique in terms of development of processes, whereby the new technologies superseded the former, as Walter Benjamin extensively explains in his writing L’œuvre d’art à l’époque de sa reproduction mécanisée(1936), a view that was later reprised by Willian Ivins in Prints and Visual Communications (1969). Could a selection of Durheim’s images offer a look into the cracks and fissures of these narratives? To begin with, let us consider the aforementioned reproduction of Durheim’s daguerreotype. It demonstrates the necessity of a reflection on the methodology used to approach photographs as archival objects and not only as visual representations. In addition to a reflection on the physical quality of photographs, a further step requires to look at how images by Durheim have been used in the early literature. For this reason, I take as an example the photograph chosen by Stenger, reproduced in the chapter devoted to Carl Durheim [Fig. 5]: a three-quarter portrait of the photographer mirrors the historian’s point of entry, by reinforcing the delineation of the trajectory of Durheim’s carreer as a slow departure from lithography and toward photography.

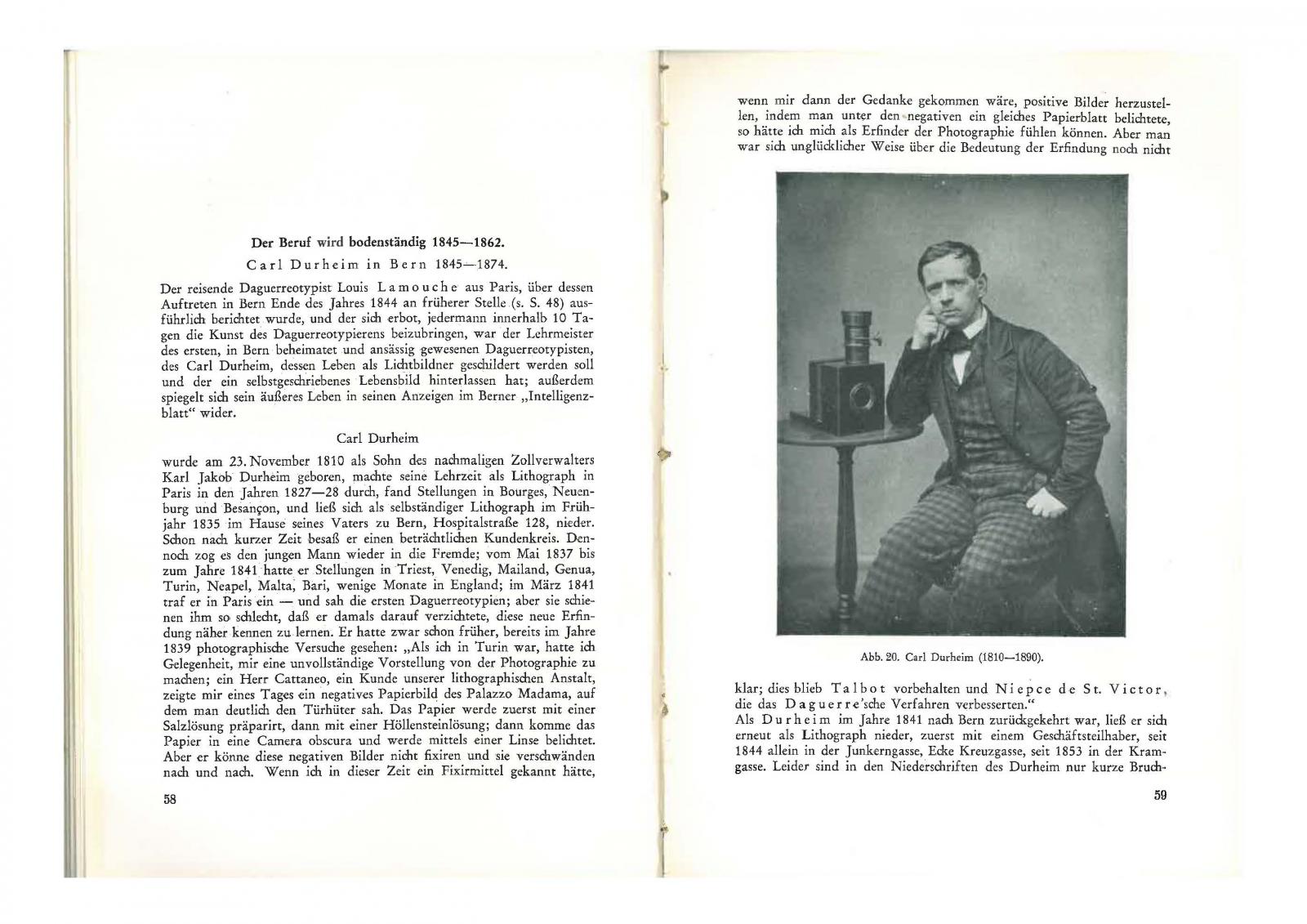

5| Erich Stenger, Die Beginnende der Fotografie im Spiegel von Tageszeitungen und Tagebuecher Wuerzburg, p. 61.

The image chosen by the Stenger and placed in the opening section of the chapter on Durheim, is a portrait of the photographer that leaves no doubts: Carl Durheim portrayed himself using photography as a photographer. The man is sitting next to a table with a camera and a lens on it. The caption unfortunately does not mention either the archive where the image is collected, or the technique. Two copies of the picture exist: one is stored at the Burgerbibliothek in Bern and the other at the Photographic Collection of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. From the appearance, one can conjecture that the photograph is an albumen print made from a glass negative, which locates the shot after 1853, and therefore belonging to the time examined by the historian. My intention is not to reject Stenger’s contention: Carl Durheim did increasingly dedicate his efforts to learn and use different photographic techniques in the course of his business activity. I would rather want to enrich Stenger’s narrative.

Recalling Ginzburg’s words, I want to shed light on those aspects, which are considered anomalies from the average perspective, and for this reason are often cut out from the chronicle, but which, I argue, instead reveal to be fully part of the narrative. In contrast to the antagonism between media (lithography and photography) that Stenger implicitly suggests, I propose to compare Durheim’s images as examples of the blurring boundaries between media. To say that Durheim presents himself at first as a lithographer and then as a photographer does not necessarily imply that he established a hierarchy of values between the two techniques, as Stenger suggests by writing that the best professionals came to photography from the arts. In addition, the idea that the transition from the arts to photography was a natural evolution due to the progress offered by the new technique does not take into account the visual economy in which Durheim operated. “Von diesen Tagen an setzen auch in der Aarestadt ein bis in die Gegenwart anhaltender Dialog zwischen der Fotografie und den bildenden Künsten ein” (Frey 1986, 11). These words, I suggest, best describe the relationship between photography and graphic arts in the specific context of the Canton of Bern is best described, in a very short time frame which is 1845-1860, i.e., before the widespread of the carte-de-visite. The different means of visual presentation moved in a circle of “aesthetic neighborhood” (Siegel 2018, 121), where the photographic processes expanded the field of the graphic arts instead of eroding or narrowing it. In the decades that immediately followed the introduction of photography, discourses about the use and value of photographic practices rose in terms of intermedia comparison. It was with the emergence of writings about the ‘histories’ of photography that a certain antagonism between media was adopted as point of view to narrate the flourishing of photography as a commercial activity in opposition to the arts. In particular, in regard to portrait photography works such as Photographie et société by Gisele Freund, first published in 1974, underscores the sociological perspective centering the discussion on the French art world and its mechanisms.

Although the history of Swiss photography is linked to the history of French and German photography, such that we can no longer speak of histories of photography by geographical origin and should rather illuminate the relationship between centers and peripheries, it is necessary to remember that the cultural and industrial context of France and Prussia were not comparable to the Swiss context in terms of culture, economy and politics. In the second half of the 19th century, Switzerland was characterized by regionalism: although the Federal State was grounded in 1848, it was neither unified by culture, language, or class, nor faith.

It is necessary to keep these specifics in mind to get back to talking about Carl Durheim’s photographic practices, which take place in Bern and for a short time in nearby Burgdorf. Durheim was a draftsman with strong roots in the Canton of Bern, so it can be assumed that his photographic practice was well placed in the context of social relations in a relatively small area. His geographical and cultural anchorage emerges in another portrait [Fig. 6], which is privately collected. With the juxtaposition of the image discussed above with this one, Durheim’s photographic practice comes vividly into light. The portrait depicts in fact Carl Durheim, sitting on a chair next to a table, with the right arm leaning on a tablecloth with floral decoration. The background shows a typical Swiss landscape view. The photograph is a calotype printed on salt paper and then heavily hand painted. From the comparison with other salt prints from the photographer, it is probable that the photograph was originally taken in the studio, where the blank background was then decorated with the landscape view only in a second moment. The Eiger-Mönch-Jungfrau mountain chain stand out on the left side; in the middle ground the Bernese Dome and Blutturm characterize the profile of the city of Bern. On the right two women and a girl standing in traditional costume underline once more the local character of the image. The picture reflects the blurring boundaries between the use of different graphic languages combined together. The image per se cannot reveal much about the author’s self-perception in regard to the use of one technique or the other. Nonetheless, it encourages reflections the indistinct boundaries between the use of graphic and photographic procedures and between the hand of the photographer and the hands of his “assistants”. The few images discussed thus far make evident that Durheim exploited an array of graphic and photographic techniques, combining them together, and that he produced and reproduced images. Using the idea of ‘intersected layers’ the images reveal the narrowing of or the departure from elements that belong to different practices. In a short time span the photographic novelties followed one another in a high experimental setting: in the specific case of Durheim the actual utilization of different techniques and methods go along with a ‘principle of contamination’ between inheriting and developing.

6| Carl Durheim, tinted Calotype, after 1849, Isabel Durheim Collection, Basel.

The 19th-century treatises insist on the unprecedented possibility of photography to imitate nature and to reproduce it faithfully: as a result, engraving has been often accused of playing the role of the unfaithful ‘translator’ of reality due to its manual component vis-à-vis photography’s mechanic and chemical procedure. In this regard, it is necessary to remember that engraving was originally designed for its purpose as a means of translating visual knowledge, in an era (the 16th century) particularly interested in promoting the works of great artists and spreading scientific knowledge. Engraving already had a documentary vocation and photography inherited the most widespread genres, such as genre scenes, portraits, topographical views and the documentation of great works. Most of the themes were designed to respond to the continuous and ever-increasing demand of tourists, a social phenomenon typical of the early 19th century, in Switzerland and abroad. For this reason, as Durheim’s portrait with painted landscape shows, the attention to the figurative qualities (portrait) and the creative tension (imaginary standpoint) go along with the attention to a taste for narrative (presentation of the subject) and informative elements (the topographic knowledge of the landscape) (Miraglia 2011, 140). Having said that, Carl Durheim’s photograph [Fig. 6] clearly shows visual models that belong to both the painting tradition and the visual language of engraving. First of all, recall that the tradition of visual arts was permeated by the objective of “illusionistic restitution of reality based on an exclusively monocular vision” (Miraglia 2011, 14), whereby photography is part of that series of technical expedients aimed at solving three problems concerning visual knowledge: (1) the quest for representation, (2) the attention to expression and (3) the far-reaching goal of communication. More specifically, the relationship between photography and painting is characterized by the conceptual continuity expressed in the “tension to merge in unity the dialectic between nature and art” (Miraglia 2011, 15). The elements of continuity within the representative scheme of painting and engraving are the presence of the landscape view and the popular figures.

A recognizable reproduction of the view of Bern is painted behind the subject: the landscape is used as a perspective artifice that describes a portion of the real; this element reminds of the use of the camera obscura and its application in the topographical depiction (veduta). The landscape was most likely added after the printing of the positive. This working practice can be confirmed by Durheim’s other portraits on salt paper, which show silhouettes of men and women standing out against a blank background, probably to allow the client to choose which landscape view to add at a later point. The dissemination of landscape view (veduta) grew particularly popular thanks to the engravings of urban scenography in the previous century (18th). These kinds of images convey a sense of depth enhanced by the presence of small figures of wayfarers – particularly popular – dear to the taste of nobles and specifically used in illustrated travel publishing. But if in the previous century the main interest fell on the precision and virtuosity in the reproduction of details and the perspectival structure of the image harking back to 15th-century scenography, the landscape view depicted behind the photographer is used with a different intention. The aim is, in fact, to enlarge the space and enhance its symbolic meaning, thanks to the choice of an extremely interesting point of view, which makes possible for the viewer the punctual acknowledgement of the place despite the observer’s unrealistic standpoint. It thus turns out that the photograph is a condensation of as much information as possible, blended together across stylistic conventions and pictorial traditions of different media. The advertisements that Stenger consulted and summarized in his writing, can either reveal the slow abandonment of lithography in favor of Durheim’s full dedication of photography, or else point toward what has been cut out by the historian’s interpretation. Durheim published the three advertisements between 1853 and 1857, on the Intelligenzblatt der Stadt Bern.

(11. March 1853) “Pour satisfaire aux demandes plus fréquentes de l’honorable public Ch. Durheim s’est adjoint un peintre habile, en sorte que des commandes en portraits etc. peuvent être livre a court délai sur plaque, papier ou ivoire, au choix de MM les amateurs.” Transl.: “To satisfy the more frequent requests of the honorable public Ch. Durheim has teamed up with a skillful painter, so that portrait orders etc. can be delivered at short notice on plate, paper or ivory, at the choice of the clients.”

(25. October 1856) “Der Unterzeichnete, welcher für Photographien die Medaille 2ter Plätze an der Pariser Weltausstellung von 1855 erhalten hat, hat sich mit einem in diesem Fache sehr geübten Maler in Beziehung gesetzt, um Porträt zu liefern, die mit den besten in diesem Genre rivalisieren können und empfiehlt sich daher sowohl für Porträts nach der Natur als auf Kopien von Ölgemälden, Aquarellen, etc.” Transl.: “The undersigned, who was awarded the 2nd place medal for photographs at the 1855 Paris World Exhibition, has contacted a painter who is very well versed in this field in order to provide portraits that can compete with the best in this genre, and is therefore recommended for portraits of nature as well as for copies of oil paintings, watercolours, etc.”

(16. Juli 1857) “C. Durheim prévient les amateurs de beaux portraits en photographie qu’il est en mesure de les livrer promptement ayant pour aides deux peintres très habiles pour ce genre.” Transl.: “C. Durheim warns enthusiasts of beautiful portraits in photography that he is able to deliver them promptly with the help of two painters who are very skilled for this genre of commission.”

The cuts carried out in Stenger’s perspective regard the implications that these three advertisements have about the collaboration with painters. Such collaboration is motivated by many reasons. The reason that recurs in all of the three ads concerns the flourishing of Durheim’s business activity. As his advertisement suggests he ‘employed’ assistants or colleagues to be able to keep up with the deliveries. This means that starting from the 1850s, Durheim might have directed his atelier less as a small-scale and artisanal business, and more and more as a pre-‘industrial’ company. With ‘industrial’ I mean that demand exceeded supply and tasks became specific. Durheim could not follow directly every single process, so he might have decided to engage personally with the first phase of the image-production, which regards the photographic process (the exposure and the printing phase) suing most probably the calotype process and later the glass negative, and to delegate to someone else with proper skills the over-painting procedures. One can conjecture that – reading between the lines – Durheim admitted his impossibility to compete with expert painters in the field of portraiture. In Bern from 1836, Johann Friederich Dietler, (Solothurn 1804-Bern, 1874) was known as a skillful painter. The presence of photography was evidently not a problem for the painter either, who actually used photography himself as basis to paint his commissions. One can conjecture that Durheim was aware of the work of his colleague and instead of competing with him, he opted for a collaboration. On the other hand, Durheim’s education as lithographer might have helped him consider his acquired knowledge as part of a more extensive practice, which did not compete with the knowledge of others. The attitude fosters the collaboration in a network of relations underlying shared interests. For sure each method was characterized by its specificity. But as it happened with photography on paper and photography on metal (Roubert 2018, 31), which were two parallel arts designated to support each other, photography and the graphic arts were far from being rivals and mutually exclusive as Durheim’s photographic collection can demonstrate. As Marina Miraglia states: “The activity of professionals [...] allows us to access the ideologies and representative/cognitive schemes typical of a given era, i.e. the different strategies of domestication of reality elaborated over time, implicitly allowing a more precise reconstruction of a given historical moment, revisited in its socio-economic and cultural values. Professionalism, in fact, inevitably reflects the needs and taste of a client, in turn inevitably linked to the most widespread visual habits of a given era. Through the activity of professionals it is possible to reconstruct in a more capillary and true way the basic cultural fabric of the history of the image of the 19th century and to reach a deeper and more realistic definition of the role played by photography and its particular iconic writing in the context of that era” (Miraglia 2011, 137). Durheim perhaps conceived himself as a photographer, but the photographic procedure might have been considered just a piece of a more expanded and organic process of image-production. He was interested in pursuing his activity as a photographer, which means that he mastered the photographic knowledge, but before the picture was completed with color, other bodies of knowledge were required. As the advertisements demonstrate, in this specific case painters were asked to collaborate. Durheim’s whole personal story is interesting because it sheds light on the inheriting and developing of working practices between graphic processes and photography, whether on paper or on metal plate, and with photography and other kinds of image production – such as painting and the graphic arts – in the timeframe 1840-1860 in the Canton Bern.

*I would like to thank Isabel Durheim to have allowed me multiple visits to her private collection in Basel.

Notes

[1] Mss.H.H.LII 98, Buergerbibliothek, Bern.

[2] 11 March 1853, Intelligenzblatt der Stadt Bern, http://intelligenzblatt.unibe.ch.

[3] Schloss Burgdorf, Inv. RS-11.830.b.

Bibliography

- Aubenas, Roubert 2010

S. Aubenas, P.-L. Roubert, Introduction, in S. Aubenas, P.-L. Roubert (éds), Les Primitifs de la Photographie, Le calotype en France 1842-1860, Paris, 2010, 16-18. - Bann 2001

S. Bann, Parallel lines, Yale 2001. - Benjamin 1931

W. Bejamin, A short history of Photography, [Kleine Geschichte der Photographie, “Die Literarische Welt”, 1931], translation by S. Mitchell, “Screen” 13/1 (1972), 5-26. - Caraffa 2011

C. Caraffa, From "Photo Libraries” to “Photo Archives”. On the epistemological potential of art-historical photo collection, in C. Caraffa (ed.), Photo Archive and the Photographic Memory of Art History, Berlin 2011, 11-45. - Caraffa 2019

C. Caraffa, Objects of value: Challenging Hierarchies in the Photo Archive, in J. Bärnighause, C. Caraffa, S. Klamm, F. Schneider, P. Wodtke (eds.), Photo-Objects: On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives in the Humanities and Sciences, Berlin 2019, 11-31. - Frey 1986

S. Frey, Mit erweitertem Auge. Berner Künstler und die Fotografie, Bern 1986. - Gasser 1990

M. Gasser, Between From Today Painting is dead and how the sun becomes a painter, “Image” 33, 1990, 8-29. - Gasser 1992

M. Gasser, Histories of photography 1839-1939, “History of Photography”, 16/1, 1992, 50-60. - Gasser 1998

M. Gasser, T. Meier, R. Wolfensberger, Wider das Leugnen und Verstellen, Carl Durheims Fanhndungsfotografien von Heimatlosen 1852/53, Zurich 1998. - Giger 2016

B. Giger, Geheimnisvolles Wirken in Berns Gassen, in Burgerbibliothek Bern (ed.), Wie die Fotografie nach Bern kam, Bern 2016,17-27. - Ginzburg 2016

C. Ginzburg, Reflexionen über einen Hypothese, fünfundzwanzig Jahre danach, in H. Wolf (ed.), Zeigen und/oder beweisen, Die Fotografie als Kulturtechnik und Medium des Wissens, Berlin 2016, 1-13. - Gropp 2018

S. Gropp, Von Angesicht zu Angesicht, “NIKE-Bulletin”, 33/2, (2018), 45-47. - Miraglia 2011

M. Miraglia, Specchio che l’occulto rivela: Ideologie e schemi rappresentativi della fotografia tra Ottocento e Novecento, Milano 2011. - Roubert 2018

P.-L. Roubert, „Dies wird jenes töten ...“. Der Niedergang der Praxis der Daguerreotypie in Frankreich durch die Publikationen von Amateuren, “Fotogeschichte” 2018, 27-36. - Siegel 2018

S. Siegel, Uniqueness multiplied: The Daguerreotype and the visual economy of the Graphic arts, in N. Leonardi, S. Natale (eds.), Photography and Other Media in the Nineteenth Century, Penn State 2018, 116-130. - Stenger 1940

E. Stenger, Die Beginnende Fotografie im Spiegel von Tageszeitungen und Tagebücher, Würzburg 1940. - Wolf 2018

H. Wolf (ed.), Polytechnisches Wissen: Fotografische Handbücher 1939 bis 1918, “Fotogeschichte“, 150/38 (2018).

English abstract

The present essay focuses on the photographic production of Carl Durheim, lithographer and photographer from Bern (1810-1890). I propose a reading of some of Durheim’s pictures and their reproductions in the existing scholarship. As I will show, unnoticed cuts carried out on the original images led to misleading interpretations because the framing erased key information about the photographer’s working practice. I will reflect on the relationship between the selection of images accompanying a scholarly text and their framing, both intellectual and physical. My attempt is to situate these reflections in the broader context of the early history of photography, which looks at the mutual intersections between graphic- and photographic- processes in the timeframe 1840-1860 in Switzerland. My hope is to integrate all the elements that have been cut and omitted in the standard narratives about a cross section of the early history of Swiss photography.

keywords | early history of photography; lithography; reproduction; Switzerland.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio.

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo/ To cite this article: Sara Romani, From cuts to clues, hidden narratives within the details of Carl Durheim’s photographic portraits, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 179, febbraio 2021, pp. 85-104. | PDF dell’articolo