In Ha Bik Chuen’s ‘Thinking Studio’ Beyond the Archive

Reflections on the Exhibition Non-history (2020) at the Hong Kong Fringe Club

Emily Verla Bovino

English abstract

1 | (left) Ha Bik Chuen studio detail, 2014. Source: M.Wong, Excessive Enthusiasm: Activating the Ha Bik Chuen Archive, in Asia Art Archive in America, October 2015. Photo: Jack Cheung of NOTRICH MEDIA, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the Ha Family. (right) Ha Bik Chuen, Shy Girl, 2002, mixed media (wood, leather and iron). Collection of Hong Kong Museum of Art. Photo: Hong Kong Museum of Art.

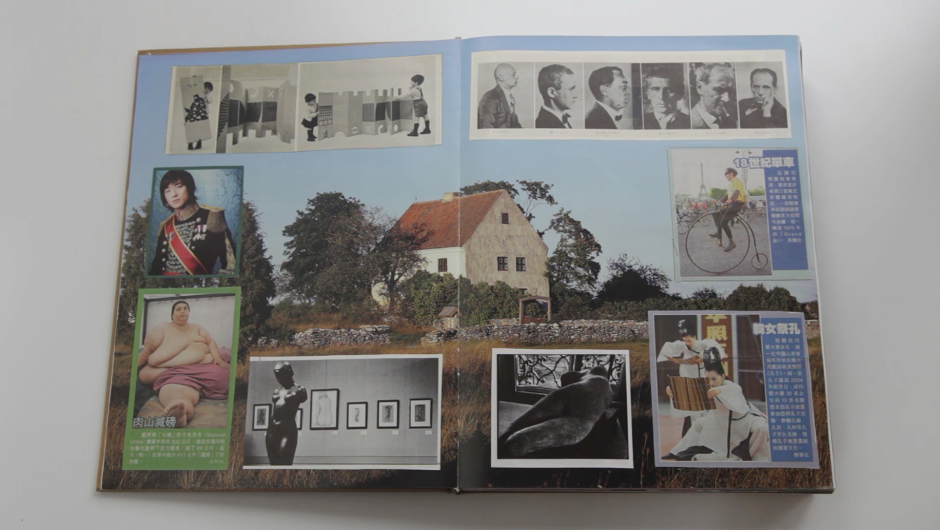

2| Still from Luke Casey’s 2015 documentation of Ha Bik Chuen’s modified book Country Interiors (2002). Source: Asia Art Archive in America, Vimeo.

Hong Kong artist Ha Bik Chuen reportedly used the Cantonese phrase 思考工作室 – “‘thinking studio’ or ‘studio of thoughts’” (Chan in Wong 2019, 66) – to describe the aggregation of materials that, over five decades, came together in his home in To Kwa Wan, Kowloon. Years of photographing Hong Kong exhibitions and urban environments – of gathering books, magazines and newspaper clippings with other print publications, ephemera, and objects – led Ha to create a space “for reference and self-learning” amid all the materials that sedimented around him (Chan 2009, 87). In an interview with artist Kurt Chan Yeuk Keung in 2009 – the year of Ha’s death – Ha’s son, Alexander Ha Cheuk-hang, commented that his father had two studios: “one for production, the other for the brain” (Chan 2009, 95) “In the latter”, his father would “read, think and meditate [靜思]” among the items he found and kept: “magazines and catalogues dumped by offices” and other “treasures” of the “urban scavenger” (Chan 2009, 95) – “useless and incomprehensible junk” that for Ha was “abstract beauty and crystallised time” (Chan 2009, 85).

The exhibition, Non-history, curated by Chinese University of Hong Kong doctoral candidate in Art History, Vennes Cheng (on view from late September to early October 2020), showed a number of items from Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ at the Hong Kong Fringe Club, together with works by two young, but established Hong Kong artists, Morgan Wong and Lee Kai Chung. Items from the ‘thinking studio’ included a selection of books from Ha’s library and digitized images of what have come to be called Ha’s “modified books” (Wong 2019, 86) accessible to viewing in the gallery on a tablet. The modified books were also present in video documentation that artist Morgan Wong used in a new video work he made for the show (According to Cheng, the video documentation was used by Wong with the permission of videographer Luke Casey who was commissioned by Asia Art Archive to record on video the modified books in 2015).

Cheng’s exhibition follows the curatorial and research strategy that Asia Art Archive (AAA) developed when it started working with Ha’s materials in Hong Kong in 2014: it invites artists to make discoveries in Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ (Wong 2019, 68). By this strategy, artist Walid Raad – in residency at AAA in 2014 – discovered Ha’s now much discussed modified books, volumes with spreads of colour images that Ha found and altered with collaged cut-outs (Wong 2015).

For Non-history, Cheng invited Wong and Lee to consult the materials of Ha’s ‘thinking studio’, since moved to Fotan, New Territories by AAA in 2016, hence no longer in To Kwa Wan (Wong 2019, 74). Cheng’s exhibition brings something new to the study of the ‘thinking studio’, not by curatorial strategy, but by research approach: her exhibition subtly suggests both a formal and historical connection to Aby Warburg’s practice of gathering images and configuring them into critical constellations, as in the famous Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (Mnemosyne Atlas, 1924-1929). The self-proclaimed “psycho-historian” (Warburg in Schoell-Glass 2008, 13) and scholar of Kulturwissenschaft (cultural science) created Mnemosyne before his death, just after his release from existential psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger’s Kreuzlingen Sanatorium in Switzerland. He was admitted to the sanatorium for a diagnosis of schizophrenia after the Hamburg Uprising in 1918 when workers captured the Hanseatic city and established a parallel government outside the Hamburg Senate (Levine 2013, 90).

Wong and Lee were born in Hong Kong in 1984 and 1985 respectively, the years the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed and made effective. The declaration prepared the 1997 transition of sovereignty over Hong Kong from Britain to China. Like the recent national security law passed for Hong Kong, the declaration was decreed in Beijing. Literary scholar and critic Howard Y. F. Choy has written of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s “architecture of ‘one country, two systems’” governance in Hong Kong, between communism and capitalism, as “schizophrenic in nature” (Choy 2007, 65). Appropriately for this association, artist Lee Kai Chung describes his film Can’t Live Without (2017) – on view in Non-history – with direct reference to the figure of the rhizome (Lee 2017) from the seminal project “on capitalism and schizophrenia” by philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (1980).

Found in ants and burrows, tubers and bulbs, viruses and fascism, the “rhizome” is an agent of ceaseless connection, heterogeneity and multiplicity that can always start up again if its “lines” are broken (Deleuze & Guattari 1980, 1987, 3-25). Between “social movement, language, mythology, geography and archival discipline”, Lee’s work also threads such lines of tangled interrelation (Lee 2020). In playing with AAA’s curatorial strategy, Cheng’s exhibition, Non-history, makes the Ha-Warburg rhizome with which the emerging scholar and independent curator is experimenting, visible. Cheng’s exhibition invites the ‘line’ of Ha’s ‘thought studio’ to be picked up and continued elsewhere, entangled in her own interest in Warburg, as well as in the research of the two artists Lee and Wong.

Ha’s ‘Thinking Studio’ and Warburg’s ‘Space of Thinking’: Rhizomatic Networks of Distance

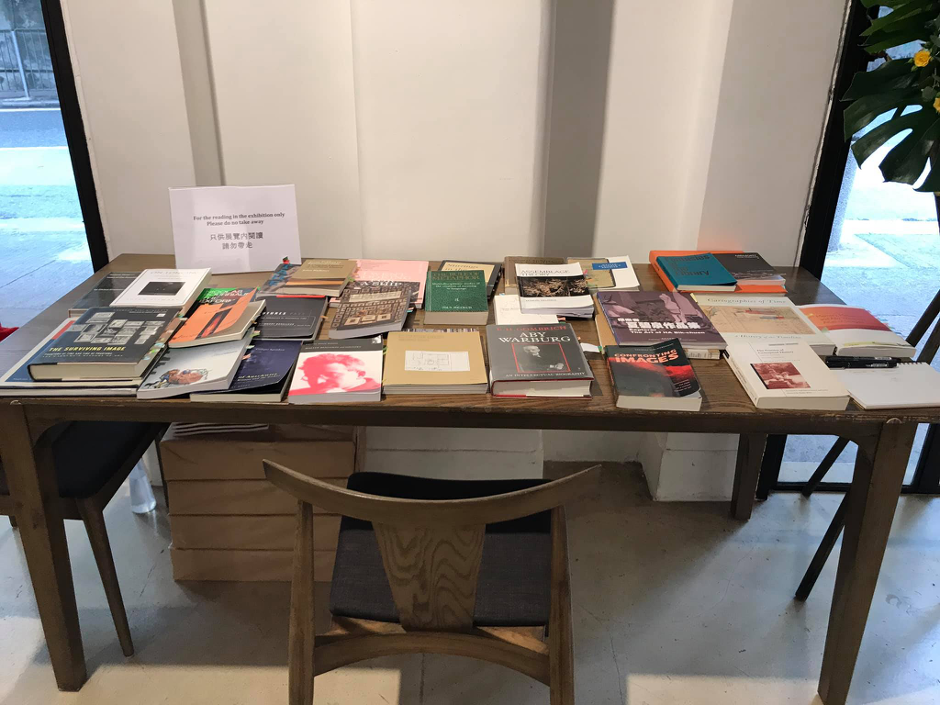

Though Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ is now predominantly known as his “archive”, Cheng’s catalogue text and exhibition walkthrough emphasize its conceptualization as what she terms, his “thinking space” (Cheng 2020, 10). Nonetheless, Cheng does not make an explicit connection between this “thinking space” and Warburg’s concept of Denkraum (space of thinking). Instead, Hal Foster, Jacques Derrida and Walter Benjamin are the protagonists of Cheng’s writing on the show. However, an anteroom to the exhibition, created with movable walls and a shelf unit of exhibition catalogues and plants, requires that visitors pass a table of books that Cheng tells visitors she has used in writing her dissertation, including, among others, several volumes about Warburg: German Studies scholar Christopher Johnson’s book on Mnemosyne (Johnson 2012); the recent translation of Georges Didi-Huberman’s seminal study of Warburg (Didi-Huberman 2016); and Ernst Gombrich’s famous but problematic Aby Warburg: An Intellectual Biography, where Denkraum was first identified as an important Warburgian concept (Gombrich 1970, 1986).

4 | Installation view from Non-history, 2020. Table of books used by curator Vennes Cheng in her research, displayed for consultation by visitors in the anteroom of the exhibition. Source: Vennes Cheng and Iris Sham.

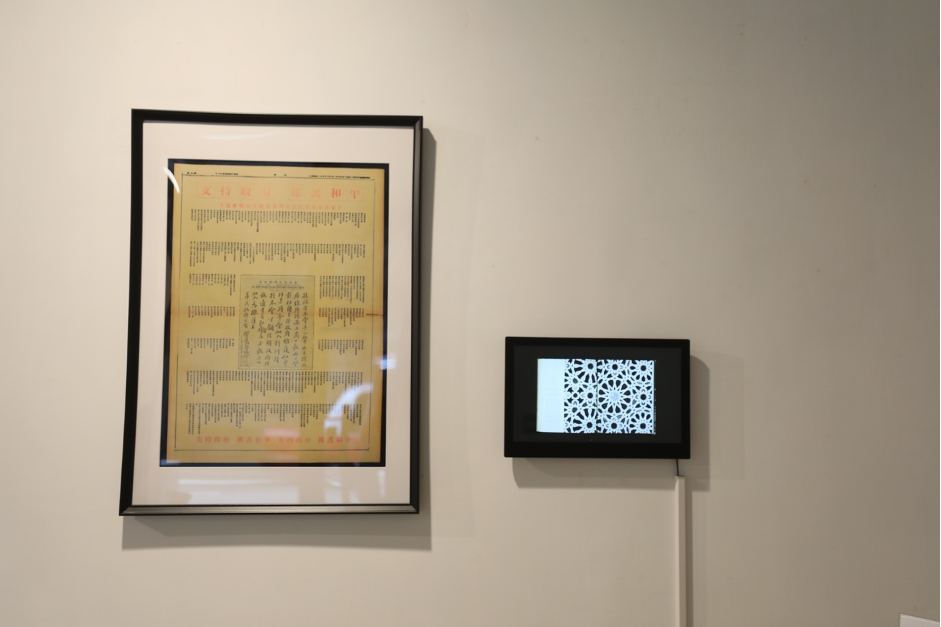

5 | Installation view from Non-history, 2020. Shelves of books from Ha Bik Chuen’s library exhibited with tablet of digitized images from the modified books (Paul Klee Rosenwind and Early Islam: The Great Ages of Man) and newspaper advertisement signed by Ha in 1967. Source: Vennes Cheng and Iris Sham.

In Cheng’s catalogue essay, only passing reference is made to Johnson’s book on Mnemosyne, not because of its extensive use of Warburg’s Denkraum concept, but for its emphasis on metaphor and memory in his critical image-making practice. Both are, indeed, important to Warburg’s Denkraum: metaphor creates a space of reflection apart from the object to which it refers, through the process of referring that takes place via agents like symbol and allegory; memory likewise offers such a space, retaining a sense of past experience by allowing thought to move into the future through a present that is able to forget. In Mnemosyne, the Denkraum operates via metonyms in images, specifically the movement of what Warburg called Pathosformeln (emotive formulas) across contexts (Johnson 2012, 88). The Denkraum are synaptic connections firing between dendritic rhizomes.

Despite the fact that Cheng’s writing about the exhibition does not make the connection to Warburg’s Denkraum, the design of the show suggests this may be what is to come in the scholar’s future work. Across from the table of books where volumes on Warburg are available for browsing in the anteroom to the exhibition, there is another shelf of books which Cheng tells visitors she selected “intuitively” from Ha’s library. The anteroom of books creates an interval between the space of the exhibition – occupied by artists Lee and Wong – and the passing traffic on Wyndham Street in Central. Together with the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, the Fringe Club occupies part of a former British colonial-era distribution outlet built in 1913 for the Dairy Farm company, which promoted milk consumption in Hong Kong. From Glenealy, vehicles rush down Wyndham Street and Lower Albert Road on either side of the slender white-striped brick structure. The anteroom performs as a buffer of sorts: an intermediary space of distance between the noisy street and the quiet voice-overs in Cantonese and Korean that come from two films by Wong and Lee on view in the exhibition.

Warburg theorized Denkraum as a space for reflection and critical contemplation – "a conscious creation of distance between oneself and the external world” (Warburg in Cirlot 2018). With universalizing anthropogenic pretensions, he claimed this distance “can probably be designated as the founding act of human civilization” (Warburg in Cirlot 2018). As he writes in his introduction to the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, “when this interval becomes the basis of artistic production, the conditions have been fulfilled for this consciousness of distance to achieve an enduring social function […]; its adequacy or failure as an instrument of mental orientation signifies the fate of human culture” (Warburg in Cirlot 2018). Warburg’s theorization of Denkraum was not achieved only in written texts, but through various degrees of distance from writing itself, in image configurations and in sketched diagrams. Cheng follows this model of theorization through the practice of distance by making curating part of the process of writing in her doctoral dissertation.

In this instance, Denkraum, however, is important not simply for the analogy with Ha’s conceptualization of the ‘thinking studio’. It offers something more: the distance to reflect upon what has been lost in Ha’s “studio” being institutionalized as an “archive” over the past decade since his death. Spanish scholar Victoria Cirlot’s essay about Denkraum in the November 2017 issue of “Engramma” (the English version is published in the February 2018 issue), is helpful in positing the issue (Cirlot 2018). At the 2017 Seminar Mnemosyne with Engramma in which Cirlot was a participant, the medievalist followed the rhizome of Warburg’s notes, diagrams and preparatory schemes for Mnemosyne, to theorize Denkraum as an important partner to the concept Zwischenraum (‘intermediate’ space). She makes the argument that the connection between the two concepts has been lost due to the importance that Gombrich gave to Denkraum over Zwischenraum in Warburg’s thought. This occurred despite the fact that both concepts are prominent in Warburg’s written introductions to Mnemosyne.

Something similar has occurred over the past six years to Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ which, as AAA researcher Michelle Wong has written, “slipped into being called Ha Bik Chuen Archive” (Wong 2019, 70). This slip – which, some might argue, was a necessary deformation in the process of conserving the materials of the ‘thinking studio’ – cut Ha’s two studios off from each other, giving more importance to the archival impulse than other intent at work in the two spaces. Likewise, Cirlot finds that though Denkraum and Zwischenraum are sometimes used interchangeably by Warburg, the fact that:

the space of thinking [Denkraum] can be an intermediate space [Zwischenraum] certainly does not imply that the notion of intermedial space [Zwischenraum] and that of the space of thinking [Denkraum] are identical. The latter comes from a need for a distance, of the creation of a space that allows contemplation and thought; while the first, in addition to alluding to that space generated between the two poles, necessarily implies a hybridity. This happens because that intermedial space is participated by both poles since in being a space of separation it is also one of meeting (Cirlot 2018).

Denkraum can be a kind of Zwischenraum, or intermedial space; but Denkraum and Zwischenraum are not mutually substitutable. Similarly, Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ does indeed include the archiving impulse, but naming it an archive obscures its very specific relationship to the artistic process – one to which Ha himself gave a name to by designating it “thinking studio”, a particular kind of space between “production” and “meditation” (Chan 2009, 95). AAA researcher Wong has talked about the ‘thinking studio’ as an externalized organ, a prosthesis that activates something “almost akin to a digestive process” – “accumulating, self-teaching, organising and processing” (Wong 2019, 71). Ha conceived of the ‘thinking studio’ as a hybrid space: not a space of distance or separation like the archive, but, to use the words of Cirlot, a space of “meeting” (Cirlot 2018). The fact that Ha had two studios suggests he saw the one for production as a space closer to the world, a channel to reinsert objects back into it for circulation. Does any archive, even a personal one, have the same degree of hybridity as the intermedial space that the ‘thinking studio’ became for Ha?

Interestingly, Taiwanese curator Hongjohn Lin, who has written of the “abuse of archives” (Lin 2018, 88), makes a similar slip in his own writing by focusing on Mnemosyne itself as an archive rather than as an atlas: as a result, in Lin’s discussion of it, Mnemosyne loses its character as a practice that developed through an architectural work of interiority that Warburg created in his library from the inside-out of the reading room he designed. Lin reminds us that Derrida’s “archive fever” popularized in contemporary art by Okuwi Enwezor’s exhibition of the same name, was inspired by Nietzsche’s attack of historicism as a “malignant historical fever” (Lin 2018, 88). To some extent the term “archive” itself has become its own malignant fever: archivism. Perhaps Ha Bik Chuen’s ‘thinking studio’ is an example of how too much attention to the archive can obscure the actual care inarchiving, focusing too much attention on the object of the ‘archive’ and its own archiving.

Anxieties around the repressed spatial aspects of Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ always seem to be present in writings about the Ha Bik Chuen Archive: Michelle Wong’s writings, for example, describe in detail the environment of Ha’s studio, developed over the course of fifty years – an apartment, approximately 600 square feet, on the top floor of an old eight-floor tenement walk-up. And yet, the ‘thinking studio’ is subsumed by the ‘archive’ in theorization. In the process, Ha’s practice has gained access to the networks of global art that he himself was eager to insert himself within but the ‘thinking studio’ has lost the opportunity to be a valued example of an underappreciated dimension of Hong Kong visual culture: the deliberate aggregation of materials in small spaces – a tactic at the intersection of critical, spatial, curatorial and artistic practice, that remains relatively neglected.

Hong Kong Interiority: Critical, Spatial, Curatorial and Artistic Practice with Interiors

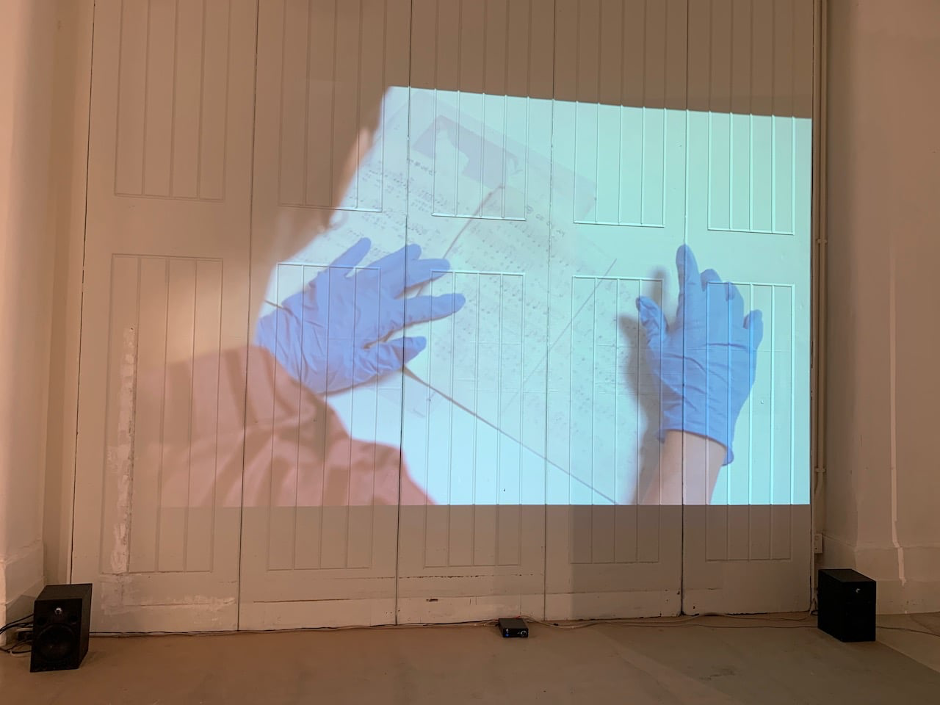

6 | Installation view of Lee Kai Chung’s Can’t Live Without (2017) at the exhibition Non-history, 2020. Source: Vennes Cheng and Iris Sham.

7 | Installation view of Lee Kai Chung’s Can’t Live Without (2017) at the exhibition Non-history, 2020. Source: Edward Sanderson, Facebook.

8 | Installation view of Morgan Wong’s How I Used to Know I Have in Fact Crossed This River (2015) at the exhibition Non-history, 2020. Source: Vennes Cheng and Iris Sham.

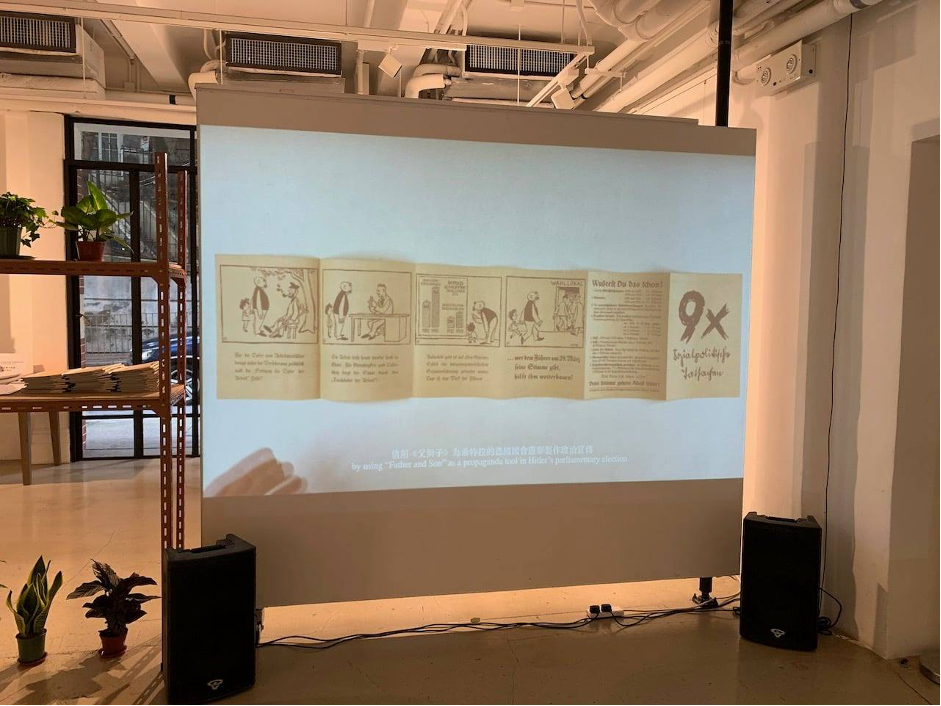

9 | Installation view of Morgan Wong’s Vater und Sohn (2020) at the exhibition Non-history, 2020. Source: Chan Sai Lok, Facebook.

10 | Detail of Morgan Wong’s The Remnant of my Volition (2013) at the exhibition Non-history, 2020. Source: Vennes Cheng and Iris Sham.

11 | Installation view of Lee Kai Chung’s They Were There (2019-2020) at the exhibition Non-history, 2020. Source: Vennes Cheng and Iris Sham.

12 | Installation view of physical and digitized items from Ha Bik Chuen’s materials on view at Non-history, 2020. Source: Vennes Cheng and Iris Sham.

13 | Installation view of the exhibition Non-history, 2020, with (left) Lee Kai Chung’s They Were There (2019-2020) and (right) Morgan Wong’s That’s How I Used to Know I Have in Fact Crossed This River (2015; 2020). Source: Vennes Cheng and Irish Sham.

More than “clutter” (Coppoolse 2019), Hong Kong aggregations make changes to the experience of an interior space which, whether a rented storage unit or a domestic interior, always express an important relationship to the body, and always seem to aim in some way to intervene in a dominant historical narrative through a minor register. Misrecognized as hoarding, this aggregating culture of curation is one of those practices that partakes in the “schizophrenia” that, as Brian Massumi writes, Deleuze and Guattari embraced in their collaboration on A Thousand Plateaus and Anti-Oedipus: “not a pathological condition” but a “positive process”, a “detachment from the world [that] is a quelled attempt to engage it in unimagined ways”: “inventive connection, expansion rather than withdrawal” (Massumi 1996, 1-3). In the Hong Kong instance, this is a kind of detachment only accessible by aggregating materials in the confined spaces that can be carved out of the world’s most expensive real estate market, allowing them the space to interact with each other while crammed together. A particular kind of object-based knowledge emerges from this practice that Ha’s work manipulated with quiet exactitude. As art historian Winnie Wong has written:

for all of its existence, Hong Kong has been regarded as a city hostile to high culture, and yet, since its founding as a port city in the mid-nineteenth century, its artists have been making art. Their work has not always been noticed; often it has been ignored. Even as the cultural and market value of art has grown greater and greater, art in Hong Kong has, counter-intuitively, been getting smaller and smaller, sometimes to the point of invisibility. Hong Kong’s contemporary art thus presents us with a unique dilemma: it manifests as a set of practices and sensibilities that evade celebration and sensationalism, and yet, more than anything, it yearns for recognition as a distinct cultural form. How can we recognise that which avoids being seen? (Wong 2018)

Artist-theorist Linda Lai points out that naming is the way something comes to be recognised; thus the names given to processes by artists are especially important, and the names given when these processes are interpreted by others, are especially risky (Lai 2020). In making Ha Bik Chuen’s ‘thinking studio’ visible as an archive, both the ‘thinking studio’ itself and Ha’s work have, to some extent, become smaller. This is not a critique of AAA, which has done the important work of taking care of Ha’s materials – of digitizing many of them and making them available online while inviting scholars, curators and artists to study and work with them. Instead, it begs the question, who is taking care of those who take care? A lack of support for research and writing about curatorial practice in Hong Kong, and an overemphasis on certain kinds of already theorized technologies – i.e. the technology of the archive – has perhaps obscured the ways that Ha’s practice leads us into a whole world of Hong Kong ‘smallness’. Perhaps losing the ‘thought studio’ was necessary. Perhaps the destruction of the ‘thinking studio’ and its reconstruction as ‘archive’ had to happen for the ‘thinking studio’ to return and finally be seen. Was this part of a ‘digestive process’ – enacted in empathy with Ha’s own practice–required to think with Ha’s ‘thinking studio’?

All this is what the artistic acts and curatorial gestures on view at Non-history seem to know and show, though Cheng does not make any of it explicit through her writing. Works by Lee and Wong – both the past works selected for the exhibition by Cheng, and the present works created by the artists in response to their discoveries among Ha’s materials – also bring attention to it. What has been lost in cataloguing and conserving the ‘archive’, is the architectural and architectonic aspects of Ha’s ‘thinking studio’. The ‘thinking studio’ as a particular expression of interiority via the small, packed Hong Kong space.

Indeed, a studio interior is the protagonist that haunts Lee’s Can’t Live Without (2017) – a single-channel film made by the artist at the Residency Changdong of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Korea. The film’s five chapters move through various characters reflecting upon the fate of known and unknown artists, their spaces and materials: artists who make it into the archives, but remain buried there, and artists for whom the artistic act remains trapped within as a fantasy rehearsed but never realized. Over images that linger with landscapes, details of paintings, and corners of sparse interiors, a female voice begins the film by recounting the reflections of an unnamed artist on the space of a future studio in Changdong: “I have never owned a studio with windows in my life”, the voice claims in Korean, envisioning what it will feel like to work in the Changdong space. Lee’s own tattooed hands appear in a first-person shot, stirring, slushing and scraping a spoon through a creamy substance that cuts to white walls and a textured white ceiling, until the camera stops to follow the trajectory of a crack, spackled and overpainted. The studio and another space, a reading room of an archive, are connected by the narrator via a “crackling sound” that the two share: the sound comes into the studio at night in an “illusion” that the narrator explains makes it seem to arrive from somewhere beyond the studio’s walls. The path of the sound suggests something will be “revealed”. The connection between the spaces brings to mind the relationship between Ha’s two studios. The voracious archive consumes both: thus, they perform as phantoms.

Subsequent chapters in Lee’s film move from the bright sunlit space of the studio to the dark subterranean corridors of an “art archive” in museum storage. Editing brings the camera in and out of the underground space in the attempt to make the viewer smell, touch and hear its affective dimensions: its dust, folders, and vinyl sheeting; the dead, phantoms, and deep-rooted mythologies that inform its order. The tale of two mountains – Bukhansan and Choansan – shows the cosmology of power in Korea, which Lee brings to human dimensions with the story of an artist whose sketches and writing are never exhumed from the archive, and a girl whose “destiny” as a pianist is just “history” because of trauma.

The film’s motion between images, and among characters, is a movement through various analogies: like the dead, the archive is immobile, except for the phantoms who murmur through it when activated by researchers; the two mountains, Bukhansan and Choansan, are metaphors for the two poles of power in the archive, imposed from above and served from below – Bukhansan, the “spiritual support” for the royal family, and Choansan the burial place for the royal family’s servants. When the ‘buried’ forgotten artist emerges as one of the murmurs in the archive, his story sounds familiar, much like that of the “hypnagogic” artist who, at the beginning of the film, recounted illusions of sound and darkness – of never having had a studio with a window: indeed, the film reveals, “only the poor artist can understand his frustrations”. The experiences of the two fuse with each other – the sketches of one are literally “buried six feet under” by curators “too exhausted” to exhibit them; the other is forced to create work on site, then discard it, because a sponsoring organization cannot afford shipping costs. The problems are all too normal. A winding drive through Changdong is edited in montage with flashes of microfilm and a hovering shot of a man finishing dry-wall seams with plaster compound. The sealed seams are like the humming mouth of the failed pianist in the film’s final chapter. The viewer never sees this mouth, but its suppressed song connects the various chapters of the film. Gloved hands motion the gestures of piano – playing that reads the sheet music beneath them while the female voice – over tells of paralyzing performance anxiety produced by raps from a teacher’s ruler. The film’s last images return to the corner of the studio shown at the beginning of the film. They lead to the black screen of cinematic conclusion with a point-of-view shot on a winding road at night lit only by headlights.

Installed alongside Lee’s ghostly Can’t Live Without is Wong’s similarly spectral That’s How I Used to Know I Have in Fact Crossed This River (2015), a scaled-down iteration of a project the artist previously showed in Hong Kong at the Para Site exhibition Imagine There’s No Country, Above Us Only Our Cities (2015). The structure is not a studio but another kind of ‘thinking space’ for waiting and watching, a patrol station for surveillance that Wong built from a historical photograph of the Lowu border-crossing between British colonial Hong Kong and China’s first Special Economic Zone, Shenzhen. As installed at Para Site’s new location in Quarry Bay in 2015, the patrol station was large enough for visitors to enter through a single doorway. Visitors could also peer out from its windows, aligned with those of the exhibition space’s upper floor in Para Site’s industrial building. At the Fringe Club, the patrol station is, instead, miniaturized to the size of a large maquette.

In 2015, Wong worked with a senior perfumer from a company that specializes in the design of synthetic scents to recreate the smell he remembers encountering when he crossed the Lowu bridge between Hong Kong and Shenzhen as a child. The miniature structure of the patrol station created for Cheng’s exhibition is infused with the same scent. Over the years, however, the bottled scent has faded, so when applied to the wooden panels of the small patrol station, it could hardly be sensed. Boundaries of difference are disappearing as territories fuse. A bottle standing on a pedestal near the structure brings attention to the smell: its label reads “The Taste of New World”. But which “New World”? By 1985, Shenzhen’s population had already hit almost 900.000; in the 1990s, it was 1.68 million then 6.33 million only a decade later. The “New World” now is neither Shenzhen nor Hong Kong, but the increasingly present reality of the two cities merged: the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Metropolitan Region. As two become one, is multiplicity lost or gained? Is what Choy called Hong Kong’s generative schizophrenia being amplified and expanded? Constrained? Or both? It is certainly ‘other’ to what it once was, but as Fred Moten writes, “the avant-garde is not only a temporal-historical concept but a spatial-geographical concept as well (…) [c]onstraint, mobility, and displacement are conditions of [its] possibility” (Moten 2003, 40).

In the statement artist Morgan Wong wrote for the exhibition catalogue of Cheng’s Non-history, he comments on feeling that his experience of Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ – that “unique fortress of Hong Kong art” – was “far from authentic” (Wong 2020, 44-46), dismantled and relocated as it was to Fo Tan, fifteen kilometres north in the direction of the mainland boundary. As Wong points out, it was not preserved like Donald Judd’s studios or restaged like Francis Bacon’s. Artists must learn to approach their work through their “future death”: they must learn to handle their materials in such a manner as to build an “artist’s estate” (Wong 2020, 46). This conclusion brings to mind Ha’s popular nickname among younger artists “Grandpa Ha” (Chan 2019, 82), implying that an inheritance of tactics for Hong Kong art can be found in his practice.

During his time among the materials of the ‘thinking studio’, Wong discovered an envelope of newspaper clippings from a comic strip that Ha conserved. The strip called Vater und Sohn (Father and Son, 1934-1937), drawn by Erich Ohser (pseudonym E. O. Plauen), only portrays figures, objects and settings with its simple graphic line: no speech bubbles. The absence of speech suggests both silent understanding between the two protagonists – father and son – and the violence of repressed expression. Plauen was, in fact, arrested in 1944 by the Gestapo for caricatures of high-ranking National Socialists like leader Adolf Hitler and Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. He is alleged to have committed suicide in his cell the day before his trial. Within this atmosphere of impending doom, Wong’s statement in the catalogue draws its own deliberate art historical father-and-son lineage with references to works by Hong Kong artist Pak Sheung Chuen and Taiwanese-American artist Tehching Hsieh.

In her walkthrough of the exhibition, Cheng discussed Chinese nationalism in contemporary Hong Kong with National Day (October 1) approaching and banners raised around the city to commemorate the establishment of the “Motherland” the People’s Republic of China, were set to wave throughout the city. The nationalist rhetoric of fatherland (German, Vaterland), motherland, and homeland is also referenced in another work by Wong on view, The Remnant of my Volition (2013). Sheets of small red flag stickers turned to show their adhesive side are framed to also include stacks of loose stickers stuck to each other in columns along the frame’s bottom edge. All three expressions – fatherland, motherland, homeland – refer to the transmission of cultural inheritance through the modernist nation-state, transforming ideology into a familial condition – something intimate; domestic.

In his text in the exhibition catalogue, as in his video, Wong plays with resituating what cultural inheritance means to him outside the bounds of sovereignty, nationality, populism and localism, through a rhizome of other artists: Pak, Hsieh, Judd, Bacon, Ha. A video of hands flipping through a copy of Vater und Sohn, which Wong found and bought on e-bay, is edited together with a video of hands turning pages in one of Ha’s modified books. The modified book in the footage is a copy of the Taschen volume Country Interiors (2002), signed and dated by Ha in 2002 after being “modified” with magazine and newspaper cut-outs: these insertions bring images from beyond the European countryside, into its interiors, as if foreseeing the global turn, even conjuring Hong Kong’s later repositioning as the world’s third largest art market. Wong’s deconstructive gestures explore the introjection of geo-political shifts, their unconscious adoption through mundane objects and emotional values.

The architectural interior returns amid lingering questions about interiority and the dynamics of introjective identification: it is again protagonist in Lee’s project They Were There (2019-2020) installed in front of Wong’s Vater und Sohn. They Were There deconstructs the object now called the “Ha Bik Chuen Archive” by looking at photographs Ha took of Hong Kong exhibitions through a past work from Lee’s own portfolio. While studying a series of photographs for research on the fashion decisions made for exhibition-going, Lee noticed the potted plants in Ha’s images of exhibition documentation and became interested in the way potted plants were being used by curators and artists “to formulate viewing routes, divide the space, change the texture of [it], and match with (…) artworks, etc.” (Lee 2020). He began to feel that there was something else going on in the very “conscious yet unconscious existence” of plants in the space (Lee 2020). Plants had been the subject of 6/100, his degree project for undergraduate study at The Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2008. Based on research conducted on NASA environmental scientist Bill Wolverton’s studies into how to use plants to remediate the issues of Sick Building Syndrome – a group of symptoms related to exposure to toxic materials and ventilation conditions of office and home interiors – Lee calculated a proportion of plants needed to purify the space of the university gallery.

They Were There focuses on exhibition documentation from the Hong Kong Arts Centre, the Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong City Hall and the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong. It was in these institutions that Lee found the most plants in Ha’s photographs. Working with the institutions themselves, as well as with the Government Records Service and the Architectural Services Department, he used plans that he located and panoramas he shot, to reengineer the environments in Virtual Reality (VR). Lee’s interviews with representatives of the institutions confirmed that little is known about where the plants came from and who decided to put them there, also revealing that the decision-making processes around exhibition-making and design are not well documented. The VR environments play on flat screens installed to lie on the ground and to rest propped in a corner. They combine Lee’s observations of plants from Ha’s photographs, with the vast interior spaces Lee documented, emptied of art and visitors.

The plants are Hong Kong art history’s bewegtes Beiwerk (accessories in motion), what Warburg in his dissertation on Florentine Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli theorized from details in paintings, like flowing hair and billowing garments –details around the painted figures that are usually the focus of iconography in art history. As Spyros Papapetros has written about Warburg’s interest in Beiwerk: these “decorative appendages” that started to take on the character of primary forces in Botticelli’s paintings (i.e. the long hair of Venus in the always popular The Birth of Venus, ca. 1485) became Warburg’s obsession as “embodiments (…) of a generalized disorder that would further stir the art historian’s [own] cosmological anxiety” (Papapetros 2010, 317).

Such cosmological anxiety is explicitly brought to the visitor’s attention in the margins of Cheng’s exhibition, the anteroom the viewer passes through again after walking through the works of Lee and Wong. In the corner were some of Ha’s books are available for browsing on a shelf, Cheng has chosen to exhibit a newspaper advertisement from 1967 from the no longer extant Chinese-language daily 真報 (Chin Po). The Chinese characters urge support for the British colonial government during a time of significant social unrest in the city that was not unlike the 1918 Hamburg Uprising: “Support the Government, Safeguard the Peace” its red headline declares, according to Cheng’s translation. What began in 1967 with actions among local workers at the San Po Kong Artificial Flower Factory – owned by the now famous Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing – became work stoppages, transit interference and large-scale economic disruption bringing injury and even deaths, including the murder of radio commentator Lam Bun, who Lee has made work about in the context of other projects. As Lee’s artistic research has shown, conventional historiography does not allow this moment its complexity: it is now known less as an example of Hong Kong’s labor struggles and social movements, than as communist infiltration from the mainland.

Non-history accommodates the detours off the fork in the road between heroes and villains. In her walkthrough of the exhibition, Cheng brings attention to one name listed in the 1967 advertisement bought in Chin Po to support the British colonial government against discontent: Ha Bik Chuen – whose art career was supported by his own artificial flower factory – is among the signatories of the advertisement. The comparison with online petitions that have been signed and circulated in Hong Kong to support recent national security legislation passed in Beijing, is evident to anyone who has been following current events. Carrie Lam Yuet-ngor, Hong Kong’s chief executive has said that since the legislation was passed “stability has been restored to society”; others assert “public discontent remains high in Hong Kong [since 2019’s anti-extradition unrest], but displaying it is increasingly risky” Ramzy, Yu & May 2020). In the smallness of its gestures, conceptual art in the city is where the most difficult thinking about Hong Kong’s current position at the centre of new Cold War rhetoric, is taking place, in critical spatial exercises and contemplative visions.

The Future of Archives: Finding a Way to Care through the ‘Thinking Studio’

The first exhibition to show materials from the ‘thinking studio’ – moving it from private use into public consumption as an ‘archive’ – took place in Hong Kong in 2015, when AAA hosted Excessive Enthusiasm: Ha Bik Chuen and the Archive as Practice (2015). Curated by a team that included Michelle Wong (who led AAA’s Ha Bik Chuen Archive Project until this year, 2020), the exhibition not only played an important part in “passaging [the ‘thought studio’] from private to public”, as Wong writes, but in cementing its very identification as an archive and strategically securing its art historical importance. Cheng’s exhibition is an example of research that this first exhibition continues to generate. It shows how, even as a phantom, Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ persists as a space for meditation, wherever it goes.

The show The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away (2017) was part of the Times Museum’s Heterotopia Trilogy on the social role of arts institutions. It shared Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ with Guangdong, the province in mainland China where Ha was born. Between 2016 and 2017, AAA researcher and curator Sabih Ahmed brought contact sheets from Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ elsewhere on the mainland, to Shanghai, in the project Striated Light, part of Why Not Ask Again?, the 11th Shanghai Biennale. Lastly, Seeing Things Being There (2017), curated by Michelle Wong, again used Ha’s materials for gestures against bordering, reflecting upon Hong Kong connections to the mainland at the end of the Cultural Revolution while looking back at the important Hong Kong exhibition Talkover/Handover (2007) about the 1997 transfer of sovereignty.

All of these projects with what is now definitively known as the ‘Ha Bik Chuen Archive’ have been supported by Hong Kong’s most important public and private cultural funds, including the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (2014-16) and the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust (2016-19). Ironically, the Chinachem Group has taken on current sponsorship (2020-21). A leading property developer in luxury apartments, offices and shopping centres in the city, Chinachem Group is among the stakeholders redeveloping To Kwa Wan – the original location of Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ – with the help of the Hong Kong government’s Urban Renewal Authority.

An upcoming exhibition of materials from the ‘thinking studio’ is planned for JC Contemporary at the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and the Arts, the former Victoria Prison in Hong Kong’s Central district. It will be compelling to see Ha’s materials at the former colony’s first prison. Archives perform sovereignty. The oscillation between production and meditation, between “retention” (retaining materials from the past) and “protention” (anticipating future events from them), between “recollection” and “anticipation” (Hui 2018, 136-138), between systems of classification and artistic speculation, between Zwischenraum and Denkraum is a reflection of how power manifests in society. In his essay Archives of the Future, Hong Kong philosopher Yuk Hui writes:

the industrialization of digital technology has brought with it an earthquake, or an avalanche, of archives, after which the landscape of the archive has undergone a massive and rapid upheaval. The information technology industry has become the point of convergence between institutional archives and personal archives (Hui 2018, 149).

Thus, “we are all archivists, since we have to be. We don’t have a choice” (Hui 2013). It is perhaps only with this ubiquity that it can become possible to see beyond the archive itself – beyond the alienation between objects and individuals that it creates – to the “question of care” that resides in it, as Hui calls it, “the temporal structure by which we can understand our existence” (Hui 2013). Refocusing on care – on the figure of the ‘thinking studio’ rather than the “efficient” and “computable” archive (Hui 2013) – might reveal all those other sensibilities of smallness – other temporalities, other narratives, other technologies, other phantoms – calling to be scavenged, scratching through walls to be heard.

Riferimenti bibliografici

- Chan 2009

K.Y-k. Chen, Ha Bik-chuen: a Self-made Artist, trans. by L.-k. Chan, “Hong Kong Visual Arts Yearbook” (2009), 82-101. - Chen 2017

L.L. Chen, On Ha Bik Chuen: Collection and Collage, “Essays. Asia Art Archive” (May 2017) [Reprinted from original publication by the Times Museum]. - Cheng 2020

V. Cheng, The Archive as Detour, in V. Cheng (ed. by), Non-history, Catalogue of the exhibition curated by Vennes Cheng, Anita Chan Lai-Ling Gallery, Hong Kong Fringe Club, Hong Kong 2020, 4-20. - Choy 2007

H.Y.F. Choy, Schizophrenic Hong Kong: Postcolonial Identity Crisis in the Infernal Affairs Trilogy, “Transtext(e)s Transcultures. Journal of Global Cultural Studies” 3 (2007), 52-66. - Coppoolse 2019

A. Coppoolse, Create No More! Clutter and Boredom, a Hong Kong Perspective, in J. de Kloet, C. Yiu Fai and L. Scheen (ed. by), Boredom, Shanzai, and Digitisation in the Time of Creative China, Amsterdam 2019, 53-76. - Cirlot [2017] 2018

V. Cirlot, Zwischenraum/Denkraum: Terminological Oscillations in the Introductions to the Atlas by Aby Warburg (1929) and Ernst Gombrich (1937), Eng. trans. by D. Carillo- Rangel, “Engramma” 153. (febbraio 2018), 83-108 [From the text first presented at Engramma’s Seminar Mnemosyne, Palazzo di Cortona, Venice, Italy. June 13 to June 16, 2017]. - Deleuze, Guattari 1987

G. Deleuze, F. Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. by B. Massumi, Minneapolis 1987. - Didi-Huberman 2016

G. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms. Aby Warburg’s History of Art, trans. by H. Mendelsohn, Pennsylvania 2016. - Gombrich [1970] 1986

E.H. Gombrich, Aby Warburg: An Intellectual Biography [Chicago 1970] Oxford 1986. - Hegyi, Wong 2017

D. Hegyi, M. Wong, Asia? Art? Archive?: Dora Hegyi in Conversation with Michelle Wong, “Mezosfera” (October 2017). - Hui 2018

Y. Hui, Archives of the Future: Remarks on the Concept of Tertiary Protention, in Y. Lei (ed. by), Archival Turn: East Asian Contemporary Art and Taiwan (1960-1989), Collected Papers from the International Symposium. Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan 2018, 129- 154. - Hui 2013

Y. Hui, Archivist Manifesto, “Mute Magazine” (May 2013). - Johnson 2012

C. Johnson, Memory, Metaphor and Aby Warburg’s Atlas of Images, Ithaca, NY 2012. - Lai 2020

L. Lai, Contemporary ‘Women’s Art in Hong Kong’ Reframed: Performative research on the potentialities of women art-makers, “Positions. (En)gendering: Chinese Women’s Art in the Making” 28, 1 (February 2020), 237-274. - Lee 2017

K-c. Lee, Can’t Live Without. Self-published: Archive of the People, 2017. - Lee 2020

K.c. Lee, They Were There, in V. Cheng (ed. by), Non-history, Catalogue of the exhibition curated by Vennes Cheng, Anita Chan Lai-Ling Gallery, Hong Kong Fringe Club, Hong Kong 2020. - Levine 2013

E. Levine, Dreamland of Humanists: Warburg, Cassirer, Panofsky and the Hamburg School, Chicago 2013. - Lin 2018

H. Lin, The Use and Abuse of Archives in Contemporary Art, in H.-y. Peng, E. Raidel (ed. by), The Politics of Memory in Sinophone Cinemas and Image Culture – Altering Archives, Oxon 2018, 87-101. - Massumi 1987

B. Massumi, Translators Foreword: Pleasures of Philosophy, introduction to Gille Deleuze and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi, Minneapolis 1987, ix-xv. - Moten 2003

F. Moten, In The Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, Minneapolis 2003. - Papapetros 2010

S. Papapetros, World Ornament: The legacy of Gottfried Semper's 1856 lecture on Adornment, “RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics” 57/58 (Spring/Autumn 2010), 309-329. - Raad 2016

W. Raad, Section 39_Index XXXVII: Traboulsi, “Notes. Asia Art Archive” (June 2016). - Ramzy, Yu, May 2020

A. Ramzy, E. Yu, T. May, On China’s National Day, Hong Kong Police Quash Protests, “The New York Times” (October 1, 2020). - Schoell-Glass 2008

C. Schoell-Glass, Aby Warburg and Anti-Semitism: Political Perspectives on Images and Culture, Detroit 2008. - Wong 2015

M. Wong, Excessive Enthusiasm: Activating the Ha Bik Chuen Archive, edited by H.Chasse, J. DeBevoise, Asia Art Archive in America [website], 2015. - Wong 2019

M. Wong, Passaging from Private to Public: The Case of Ha Bik Chuen’s Archive in Hong Kong, “Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia” 3, 2 (October 2019), 65-90. - Wong M. 2020

M. Wong, Not Titled, in V. Cheng (ed. by), Non-history, Catalogue of the exhibition curated by Vennes Cheng. Anita Chan Lai-Ling Gallery, Hong Kong 2020, 34-36. - Wong 2018

W. Wong, On Smallness in Hong Kong Art, “M+ Stories: Podium” 1 (January 2018).

English abstract

The fever for archives benumbs. This essay explores the daze through the example of the Ha Bik Chuen Archive, a documentation, conservation and digitization project at Hong Kong’s Asia Art Archive (2014-ongoing). Working with the distinction between Aby Warburg’s concepts of Zwischenraum (intermediate space) and Denkraum (space of thinking) theorized by philologist Victoria Cirlot, it stakes a claim for differentiating between the ‘archive’ and what Hong Kong artist Ha Bik Chuen called his 思考工作室 (Cantonese for ’thinking studio’ or ‘studio of thoughts’). Ha used the term ‘thinking studio’ to describe the aggregation of materials that, over five decades, came together in his home in To Kwa Wan, Kowloon. AAA’s work with Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ transformed it, not only by making it public, but by presenting it and circulating it as a new object called “archive”. In describing the “industrialization of digital technology”, philosopher Yuk Hui has written, “we are all archivists, since we have to be. We don’t have a choice”. What is lost when all aggregations of materials are subsumed under the ‘archive’? The exhibition, Non-history (2020) curated by Vennes Cheng at the Hong Kong Fringe Club, showed items from Ha’s ‘thinking studio’ alongside works by artists Morgan Wong and Lee Kai Chung; it also suggested connections between the ‘thinking studio’ and Aby Warburg’s practice of gathering images and creating critical constellations, as in the famous Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (Mnemosyne Atlas, 1924-1929). By making an explicit connection – not made in the exhibition – between Ha’s “thinking space” and the theorization of Warburg’s Denkraum, the essay opens a passage back to the ‘thinking studio’ that, by venturing through the critical interventions of artists Wong and Lee, reveals other sensibilities for smallness – other temporalities, other narratives, other technologies and other phantoms – calling to be scavenged from under the voracious ‘archive’.

keywords | Ha Bik Chuen; Aby Warburg; Denkraum; Zwischenraum; archive; thinking studio; Mnemosyne Atlas; Yuk Hui; Victoria Cirlot; Morgan Wong; Lee Kai Chung; Vennes Cheng.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: E. V. Bovino, In Ha Bik Chuen’s ‘ Thinking Studio’ Beyond the Archive. Reflections on the Exhibition Non-history (2020) at the Hong Kong Fringe Club, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 180, marzo/aprile 2021, pp. 161-182 | PDF