Digging into a Display

The ‘Voices’ of the Bronzes from San Casciano dei Bagni

Jacopo Tabolli

Abstract

Introduction

The 2021–2022 excavation seasons at the Etruscan and Roman thermo-mineral sanctuary of Bagno Grande at San Casciano dei Bagni (province of Siena) brought to light a votive deposit of bronze statues and statuettes exceptionally well preserved within a travertine pool (Mariotti, Tabolli 2021; Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023; Osanna, Tabolli 2023). This sacred pool filled by hot water and mud constituted the centre of the shrine, although the complete extent of the sanctuary has not been defined yet. Reading the complex sequence of ritual depositions into the pool, that took place from the III century BC to the V century AD, resulted in the identification of a series of well-defined actions performed by ancient social agencies that marked the life of the sanctuary for over seven hundred years. From Etruscans to Romans, from Paganism to Christianization, identities combined resilience and transformation. The stratification of multiculturalism and multilingualism is indeed one of the main characteristics of the sanctuary of Bagno Grande (Tabolli 2023a).

The intact archaeological context is allowing a large group of scholars involved in the excavation, study and publication of the site to undertake the complex process of unlocking this sacred site and its landscape. Alongside the scientific efforts to provide preliminary results on the excavation and its finds to the academic community, a consistent series of public lectures took place for the local community of San Casciano dei Bagni, as a way to thank the Municipality for taking on the responsibility of requesting the excavation permit, funding the dig, and hosting the student participants. The announcement by the Italian Ministry of Culture of the discovery in November 2022, followed by an intense period of conservation, allowed for the opening in June 2023 of the exhibition “Gli dei ritornano. I Bronzi di San Casciano [The return of Gods. The Bronzes of San Casciano]” (Osanna, Tabolli 2023) at the Presidential Palace at Quirinale, curated by the General Director of Museums of Italy Massimo Osanna and Jacopo Tabolli from the University for Foreigners of Siena, together with a scientific committee formed by Vilma Basilissi, Mauro Buonincontri, Gian Luca Gregori, Luigi La Rocca, Emanuele Mariotti, Giulio Paolucci, Massimiliano Papini, Giacomo Pardini and Ada Salvi. Guglielmo Malizia and Chiara Bonanni developed the architectural design of the exhibition.

Moving beyond the exceptionality of the Etruscan and Roman bronze statues and statuettes, this exhibition focuses on the cultural biography and the contextual potentiality of understanding bronze artefacts as a way to narrate the resilience of a sacred place and its thermo-mineral waters. Moreover, this exhibit focuses on the ‘voices’ recorded by the inscriptions on bronze statues and ex votos, bringing again to life the social complexity of ancient communities that recognized, through merging here, this peripheral sacred space as one of their ‘centres’.

The exhibition is divided into two main sections. While most of the rooms are dedicated to the findings of 2022, the first two rooms present to visitors the landscape around San Casciano dei Bagni and the history of research. It is a spiral of space and time, that places Bagno Grande within the larger picture of the archaeology of the region and along the timeline of the I millennium BC and the first half of the I millennium AD.

The Exhibition

I. Chiusi: a landscape of sacred thermo-mineral waters

1a-b| Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, First Room: the territory of Chiusi; a) the Etruscan period; b) the Roman period (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

On the southern border of the province of Siena, along the slopes of Mount Cetona, the presence of hundreds of springs testifies to one of the richest areas of thermo-mineral waters in Italy (Tabolli 2023c). Historical sources mention the name of the Fontes Clusini, the springs of Chiusi (Osanna 2023). Bronze offerings have been dedicated to these springs since the Bronze Age (II millennium BC). The exhibition opens with the Late (Recent) Bronze Age sword from the Antro della Noce in Cetona (Cuda 2023). A biconical urn from the necropolis of Cancelli (Palmieri 2023) and a bronze belt buckle from the necropolis of Tolle (Bischeri 2023) introduce the visitor to the emergence of the proto-urban sites of Etruria, during the Early Iron Age, and then to the Orientalizing culture. Already in the Archaic period (VI century BC), in the territory controlled by the Etruscan city-state of Chiusi, there were many sanctuaries near the hot springs, such as the sanctuary of Sillene, in Chianciano Terme, where Aplu and Tiur (Apollo and the Moon) were celebrated (Paolucci 2023a; 2023b). Parts of bronze statues, a chariot and a lunar crescent were found within the hot spring. A second lunar crescent from the Borgia Collection at the Vatican Museums is the first inscribed bronze on display, dating to the VI and V centuries BC. It is the first ‘voice’ in bronze in this exhibition (Sannibale 2018; 2018-2019; 2023). The inscription reads:

mi tiiurś kaθuniiaśul “I (am) of the Moon Kathuniaś”.

During the Hellenistic period (III and II centuries BC), bronze anatomical votives (ears, eyes, and infants in swaddling clothes) testify to the medical practices that took place in these sanctuaries, such as at Campo Muri in Rapolano Terme, where a large healing complex was discovered (Salvi, Tabolli 2022; Salvi 2023b). In 89 BC, the population of Chiusi received the Roman citizenship. Compared to other regions in Etruria, in the area of Chiusi the clash with Rome was more gradual. In the center of the room, the statue of a man wearing a toga is on display (Papini, Maggiani 2023a). This statue had been looted from the area of Chiusi or Perugia and recovered in the illegal market by the Comando Carabinieri Tutela del Patrionio Culturale in 2007. The man in the toga represents the need to appear and dress ‘like the Romans’ while preserving Etruscan heritage and identity. The inscription (Wylin 2001; most recently Papini, Maggiani 2023a) on the lower part of the toga reads:

au.ceisina.la.eiser / aś.θuflθas. / turce.

Aule Ceisina, son of Larth, to the gods of Thufltha, has dedicated.

The continuity in the deposition of bronze offerings in the thermo-mineral springs during the Roman times demonstrates the continuation of ritual and cult activities. A bronze lamina, incised with a schematic male head in profile, was offered to the Nymphs and found at Ponte Rovescio, close to Chiusi, along the ancient via Cassia (Paolucci 2023c). The words incised are:

Sentius [L]ucilianus Nymphis aq[uae] Ogulni/ae d(onum) p(osui)t

Sentius Lucilianus gave this as a gift to the Nymphs of the sacred waters of Ogulniae.

Finally, three bronze mask-helmets from the territory of Rapolano, dated between the I and II centuries AD, probably corresponded to a votive deposit linked to Roman soldiers (Salvi 2023c). From the Late Bronze Age to the Empire, the visitor can see the continuity in this territory of the deposit of bronze offerings at thermo-mineral springs.

II. Previous discoveries at San Casciano dei Bagni

2 | Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, Second Room: history of archaeological research at San Casciano dei Bagni (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

The territory of San Casciano dei Bagni lies on the ancient road connecting Chiusi with the city of Vulci and the seaside. Over forty hot springs are located in the valley of San Casciano along the River Elvella. The Bagno Grande (the Great Bath) corresponds to the richest spring, with 25 liters of water per second, at over 40 degrees Celsius. Shortly after the 1575 earthquake, the Medici built a pool and a small portico on top of the ruins of an Etruscan and Roman sanctuary (Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023). Two altars, dating to the end of the II century AD, located within the ruins of the sanctuary and dedicated to Apollo, Asclepius and Hygeia, were found in 1585 (Gregori 2021). One of these altars found in the Reinassance is on display in the second room. The inscription reads:

Pro salute Cai et Pomp[o]= niae n(ostrorum) liberọ[ru]= m[q]ue eor[um], Aesculapio et Hygiae sacr(um). Ephaestas lib(erta) v(otum) l(ibens) m(erito) s(olvit).

For the health of our Gaius and Pomponia and for their heirs, sacred to Esculapius and Hygeia, the freedwoman Hephaesta discharged the vow freely, as is deserved.

Already in 2020, prior to the beginning of the excavation within the votive deposit inside the travertine pool, two additional inscribed altars were found on top of the rim of the pool. The first altar is sacred to Isis, while the second one is on display (Gregori 2023b) and reads:

P(ro) s(alute) Asini Fabiani et Eruciae Triari= ae et liberis eor(um) Fortunae Primige= niae Abascantianus servos (!) actor d(e)d(icavit).

For the health of Asinius Fabianus and of Erucia Triaria and their heirs, Abascantianus, administrator, dedicated as a gift to Fortuna Primigenia.

The occurrence of similar names between the altars suggests the predominance of senatorial families at the end of the second century, patrolling this lower part of the territory of Clusium and the sanctuary of Bagno Grande. In the sixteenth century, just one mile to the south of Bagno Grande, at the spring of Doccia della Testa, where another Roman sanctuary of the area was located, a marvelous marble copy of the Aphrodite of Doidalsas, also known as the Bathing Aphrodite, was discovered and dates to the beginning of the II century AD (Ghisellini 2009). In the same locality, in 2004, a votive deposit with bronze offerings came to light (V century BC to the III century AD) (Iozzo 2014). On display are a breast, an ear, a snake, and two male figurines, possibly portraying male heroes or gods (Arbeid 2023b). In addition, this second room has three tombs on display. These are cremations from the local small necropolis of Balena (a toponym that comes from Balnea, the Baths), dating to the end of the II and early I century BC and were probably connected to the community working for and around the sanctuary (Maggiani 2014; Mariotti 2023). The tiles closing the cremations bear inscriptions in Etruscan and Latin that testify to the complex process of Romanization for this peripheral community. The inscriptions read as follow:

Dromos 4, loculus 82: θana. veinei / crepesa / numsis. Normalized Etruscan alphabet.

Dromos 2, loculus 24: TANA / ORSMINEI / CASRTOS. Etruscan inscription in Latin alphabet.

Dromos 2, loculus 104: ARUSEIRLA /ALBONIA. Latin inscription.

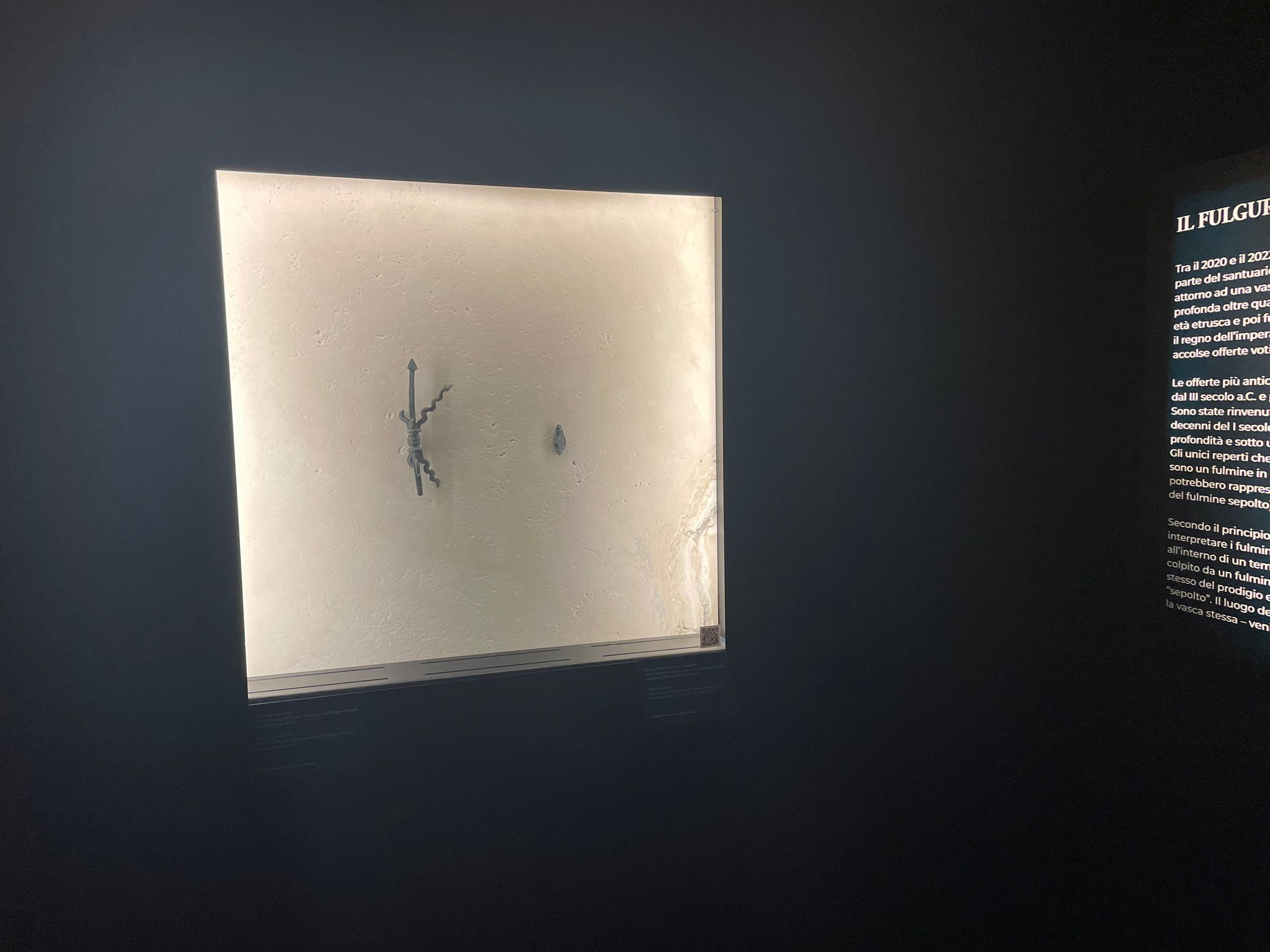

III. Burying the lightning bolt

3 | Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, Third Room: the fulgur conditum (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

The core of the Etruscan and Roman sanctuary came to light at Bagno Grande between 2020 and 2022. The ancient building encircled a sacred pool – over 4 meters deep – made of travertine blocks. An earlier Etruscan pool, located below the Roman one, was restructured and enlarged at the time of Emperor Tiberius (I century AD). Votive offerings were deposited into the water until the late IV century AD. The earliest statue offerings date to the III century BC and continue throughout the II and the I century AD. They were deposited all together at the beginning of the I century AD into the earliest pool, at a depth of more than three meters, underneath a compact layer of terracotta tiles. The only artifacts associated with the tiles are the representation of a thunderbolt in bronze and a prehistoric flint arrowhead. These objects probably symbolize a fulmen conditum, the ‘burying’ of a thunderbolt (Tabolli 2023b). According to the ars fulguratoria – the Etruscan tradition of reading the lightening – the objects struck by lightning within a sacred place had to be buried. The place of ritual burial – in this case the pool – became a bidental.

IV. The Sacred Spring

4 | Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, Fourth Room: the Spring (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

For more than 700 years, from the III century BC to the IV century AD, the thermo-mineral waters of Bagno Grande, collected in the sacred pool, received bronze and plant offerings. Despite the passage of centuries and the political transformations between Etruscans first and then the Romans, the rites had always focused on the hot water, testifying to its therapeutic benefits. Fortuna Primigenia and Apollo were the deities protecting the spring from its earliest times. At the time of the Roman Empire, one should add Asclepius, Hygeia and Isis. Nevertheless, the spring itself is at the center of rite and cult, at least since the II century BC. The name of the sacred spring appears in Etruscan and Latin inscriptions (Maggiani 2023; Gregori 2023a). On the skirt of a female goddess (dating to the mid-II century BC) wearing a crown resembling the towers of a city, and holding a snake and a patera, a beautiful inscription in Etruscan reads:

au.scarpe.au.velimnal.persac cver.flereś.havensl

Aule Scarpe, son of an Aule and of a Velimnei, from Perugia (gave) as a sacred gift to the Goddess of the Spring.

This is the first time that the name of the Etruscan city of Perugia is recorded on an inscription. Five dedications to the Flere of Havens in Etruscan can be read as “to the goddess of the Spring” (Maggiani 2023). The root for the word “Havens” is the same as in “Aventine”, one of the hills of Rome. According to the Roman historian Varro, the River Avens existed once upon a time on the Aventine. The statue of a naked, sick man presents a Latin inscription on its right leg (Papini 2023a; Maggiani 2023). The inscription reads:

L. Marcius L.f. Grabillo hoc signu(m) et signa sex et femina ap pedibus ad inguen sex Fonti calidae v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito).

Lucius Marcius Grabillo, son of Lucius, (offered) this statue and other six statues and six legs, from the foot to the inguinal, to the Hot Spring of Calida, (and) discharged the vow freely, as is deserved.

In Latin, the dedication to Fons Calidae, to the spring of the hot water, possibly testifies to the Nymph/Lymph of the spring and especially to the transition from Etruscan to Latin of the sacred power of this spring.

V. A woman in the act of offering

5a-b | Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, Sixth Room: a-b) the toga wearer (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

The corridor that moves from the spring to its statues presents an AI image that portrays the statue of a woman in the act of offering, wearing a chiton and a mantle. This bronze statue is an Etruscan masterpiece of the II century BC (Papini 2023a), currently in conservation. The hair with thick wavy curls frames the face and two long twisted braids fall on the chest. Her ornamentation is rich: earrings with a rosette button and a conical pendant, a ribbon necklace, and bracelets on both wrists. The statue resembles other examples with a mantle that are widespread since the early Hellenistic period. Since the III century BC, similar female and male figures represented in the act of offering characterize the sanctuary as a space for meeting and praying.

VI. A man wearing a toga

6a-b | Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, Seventh Room: a-b) Apollo and Medicine (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

Among the statues of deities, the statues of men and women in the act of offering had a fundamental role within the sanctuary. These images represented simultaneously the actor of the offer and the offering itself. The fact that for over seven hundred years the dedications in the hot water were mostly in bronze implies that alongside the dedicatory value of each statue, they were also offered because of their value in metal. The quantity of metal, in copper alloys, used to create the statues constituted the main currency of offerings to the sacred spring of the sanctuary. The young toga wearer (Papini 2023a; Papini 2023b) on display has a tunic and a mantle that wraps around the body. He has closed shoes with two corrigiae (boot-like shoes with leather bands) similar to the famous bronze of the Arringatore, exhibited in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence, but discovered in Pila, a locality close to Perugia. The statue from the Bagno Grande of San Casciano is contemporary to the Arringatore and is part of a group of about thirty specimens dating back to the transitional age, i.e., in the very first years of the I century BC. The height of this and of the other statues, about three Roman feet (just under a meter), represents the so-called “honored measure” – as described by Pliny – of the dedicated statues.

VI. Apollo and Medicine

7 | Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, Eighth Room: the system of offerings (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

Apollo or “Aplu” in Etruscan, is the deity that persists during the entire life of the sanctuary, both in Etruscan and Roman times. He is mentioned on the dedications inscribed on the II- and III-century AD travertine altars. Nevertheless, the earliest bronze statue depicting the god was discovered into the ritual filling of the sacred pool hit by the thunderbolt and closed at the beginning of the I century AD. This image of the deity follows a peculiar scheme, in a somehow unstable balance, with his feet partially lifted off the ground, as in a dance. The young god is portrayed in the act of shooting an arrow with an outstretched bow. The statue dates from around 100 BC (Papini 2023c). On Apollo’s arms, as well as a short distance away, two exceptional bronze plaques were placed in the mud, characterized by ‘polyvisceral’ relief decorations. These representations of viscera appear as they would in a human body opened by a cut. On the base of one of the ‘polyvisceral’ plaques, a Latin inscription mentions a dedication to Fortuna (Tabolli, Gregori 2023).

Atimetus Sulpi/ciae Triariae / actor Fortunae / v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito).

Atimetus, administrator of Sulpicia Triaria, to Fortuna has discharged the vow freely, as is deserved.

The discovery of a surgical tool in the deposit – a thin surgical gouge – confirms the reference to medicine. The presence of medical tools associated with anatomical ex votos and especially with the ‘polyvisceral’ plaques in a thermal and votive medical context constitutes an exception, when compared to contemporary deposits, and confirms the presence of medical doctors working at the thermal sanctuary of San Casciano.

VIII. The system of offerings

8 | Exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale, Eighth Room: the coins (photo by Silvia Viva, Quirinale).

Bronze and plant offerings continued to be deposited atop the layer containing the thunderbolt until the end of the IV century AD and were sealed with tiles at the beggining of the I century AD. These are mostly in the form of coins; in fact, more than 5,000 specimens have been recovered (Pardini 2023; Pardini, Carbone 2023). The value of the offer that binds hot water and bronze remains the same. In this final part of the exhibition, we present the system of offerings, consisting of a complex series of depositions that took place over the centuries inside the pool. Two portrait heads represent the men and women who travelled to be healed and to pray at the sanctuary. A male portrait of the I century BC ‘speaks’ through the inscription on its neck (Papini, Maggiani 2023b):

nufreśi: nufrznaś:ar persile:flereś.havensl tenine:tlenaχieiś

On behalf of Nufre, of the Nufrzna family, son of Arnth, from Perugia, to the Goddess of the Spring, it is placed as a vow to be discharged.

This inscription resembles in its structure the dedication of the statue of the Arringatore. The figures of small devotees are on display at the center of this final room. Especially the elegant statue of the putto of San Casciano testify to offerings of a smaller size (Tabolli, Maggiani 2023). The voice of the putto is indeed the voice of a mother, Ancari, for her baby represented with the characteristic bulla, holding a bird (lost) and a fruit.

persile.ancariale.amθnesle eca.cver. clen.ceχa flereś.havenśl tenine.tlenaχeiś

On behalf of Ancari (wife of) Amthne, this object, as a sacred gift, in favour of the child, to the Goddess of the Spring, was placed as a vow to be discharged.

Similarly to the votive deposit of Doccia della Testa, a few bronze animals were offered into the pool, as is the case of a lizard (Arbeid 2023a; Arbeid 2023b). From legs to arms and feet, from breasts to uteri and penises, from ears to masks and faces, the world of offering bronze body parts – the so-called anatomical votives – demonstrates the complex system of dedications for healing and, at the same time, testifies to the medical treatments that took place at the sanctuary (Pacifici 2023a; De Lucia Brolli 2023). A foot is talking through the inscription by a freed woman (Pacifici, Gregori 2023).

[Fort(unae)] / Primogen(iae) / v(otum) s(olvit) / Minicia / Myrine.

To Fortuna Primigenia, discharged the vow, Minicia Myrine.

Similarly, an offering to Fortuna Pimigenia appears incised, in Latin, behind an ear.

A. Nonius A.f. Viscus v(otum) s(olvit) F(ortunae) P(rimigeniae) l(ibens) m(erito).

Aulus Nonius, son of Aulus Viscus, to Fortuna Primigenia has discharged the vow freely, as is deserved.

Together with the bronzes, this final room presents the exceptional organic finds. In fact, the thermo-mineral spring of Bagno Grande has preserved hundreds of organic offerings, mainly plants (Buonincontri 2023). Remains of different fruits, portions of branches and a wooden comb were associated with the depositions of coins that took place during Roman Imperial times, between the Flavian age and the beginning of the III century AD. The presence of a series of perfectly preserved stone pinecones is outstanding. A few specimens of peaches inside the sacred pool can be linked to ritual consumption and votive use of this fruit, which is considered to be of ‘exotic’ origin (coming from Persia since the I century AD). Finally, the parts of branches, found in the pool of the sanctuary, showed traces of artificial cuts. A decorated comb was also found within the deposit. This set of evidence highlights the complex system of offerings “beyond bronze”. It is important to stress that despite hundreds of plant offerings, no animal bones come from the deposit of the sacred pool, except for eggs, that were laid in contact with the statues.

The exhibition ends with the display of Roman coins in context (Pardini 2023; Pardini, Carbone 2023). Among the corpus of votive offerings, coins allow us to retrace the events that took place at Bagno Grande during the various phases of the Roman period, between the Late Republican age and the Imperial times. The specimens on display represent a small but significant selection of all the coins discovered in the sacred pool during the 2021 and 2022 excavation seasons, amounting to over 5,300 pieces and covering a vast chronological span that roughly ranges from the last decades of the I century BC to the IV century AD. The extraordinary characteristic of these coins lies mainly in their excellent state of preservation, many of them freshly minted. This circumstance suggests that these coins had not circulated or had circulated very little, i.e., that they left the mint in Rome and probably arrived in the sanctuary near their date of issue. This is the reason why we can hypothesize that uniform nuclei of coins, more or less chronologically consistent, were offered and deposited at Bagno Grande, between the Tiberian and Trajan times.

Back to Bagno Grande

The opening of the exhibit at Quirinale constitutes the end of a complex process of analyzing context and artefacts discovered between 2021 and 2022 at Bagno Grande. In late June 2023, the excavation began again under the guidance of Emanuele Mariotti, Ada Salvi and Jacopo Tabolli, and is focusing on understanding the spatial and chronological extent of the sanctuary. Back to the field, the sanctuary is again revived by the presence of more than fifty international students, a multicultural and multilingual environment where new voices encounter the complexity of this archaeological site. Excavation will continue until October 2023 and will be accompanied by public presentations of the results to the local community and by the workshop “Etruscologia_Medicina_Terme” (Etruscology_Medicine_Thermal sites), which will focus on the interaction between archaeologists involved in this research project and international scholars expert in ancient thermal complexes with medical doctors, in a continuous effort to bring new ‘voices’ for the understanding of the past of San Casciano dei Bagni.

Bibliographical references

- Arbeid 2023a

B. Arbeid, I piccoli animali in bronzo: indizi di un’assenza, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, 167-179. - Arbeid 2023b

B. Arbeid, Ex voto dalla stipe di Doccia della Testa, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 66-69. - Arbeid 2023c

B. Arbeid, Lucertola, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 118-119. - Bischeri 2023

M. Bischeri, Affibbiaglio in bronzo dalla tomba 709, necropolis di Tolle, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 42-43. - Buonincontri 2023

M. Buonincontri, Legni e frutti, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 144-147. - Cuda 2023

M.T. Cuda, Spada a lingua da presa da Cetona, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 37-39. - De Lucia Brolli 2023

M. A. De Lucia Brolli, Tra volti e maschere, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 142-143. - Ghisellini 2009

E. Ghisellini, L’Afrodite accovacciata del tipo Doidalses da San Casciano dei Bagni, in C. Braidotti, E. Dettori, E. Lanzillotta (a cura di), Ou pan ephemeron. Scritti in memoria di Roberto Pretagostini, Roma 2009, 663‑685. - Gregori 2021

G.L. Gregori, Una famiglia senatoria del tardo II secolo d.C. Le nuove iscrizioni del Bagno Grande, in Mariotti, Tabolli 2021, 193-199. - Gregori 2023a

G.L. Gregori, Iscrizioni latine su votivi in bronzo: divinità, devoti, formulari, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, 195-203. - Gregori 2023b

G.L. Gregori, Due altari dal Bagno Grande, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 12-75. - Iozzo 2013

M. Iozzo (a cura di), Iacta stips. Il deposito votivo della sorgente di Doccia della Testa a San Casciano dei Bagni (Siena), Firenze 2013. - Maggiani 2014

A. Maggiani, La necropoli di Balena. Una comunità rurale alla periferia del territorio di Chiusi in età medio e tardo ellenistica (II-I sec. a.C.), in M. Salvini (a cura di), Etruschi e romani a San Casciano dei Bagni. Le Stanze Cassianensi, Roma 2014, 51-60. - Maggiani 2023

A. Maggiani, Le iscrizioni etrusche su votivi di bronzo. La divinità e i suoi devoti, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, 181-193. - Mariotti 2023

E. Mariotti, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Il santuario ritrovato. Nuovi scavi e ricerche al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2021. - Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023

E. Mariotti, A. Salvi, J. Tabolli, (a cura di), Il santuario ritrovato 2. Dentro la vasca sacra, Livorno, 2023. - Osanna 2023

M. Osanna, Nel santuario termale di San Casciano dei Bagni (SI): pratiche religiose e materialità degli oggetti, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 2-10. - Osanna, Tabolli 2023

M. Osanna, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Gli dei ritornano. I bronzi di San Casciano, Roma 2023. - Pacifici 2023a

M. Pacifici, Votivi anatomici: gambe, piedi e braccia, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 130-133. - Pacifici 2023b

M. Pacifici, Utero, seno, pene, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 138-141. - Pacifici, Gregori 2023

M. Pacifici, G.L. Gregori, Votivi anatomici: le orecchie, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 134-137. - Palmieri 2023

S. Palmieri, Ossuario biconico da Cetona, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 40-41. - Paolucci 2023a

G. Paolucci, Offerte in bronzo dalle aree sacre del territorio chiusino, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, 87-99. - Paolucci 2023b

G. Paolucci, Statue dal santuario di Tiur-Aplu di Chianciano Terme, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 44-47. - Paolucci 2023c

G. Paolucci, Tabella in lamina di bronzo da Ponte Rovescio, Chiusi, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 60-61. - Papini 2023a

M. Papini, Immagini di divinità e devoti di bronzo, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, 117-135. - Papini 2023b

M. Papini, Statua di togato, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 90-93. - Papini 2023c

M. Papini, Statua di Apollo, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 94-97. - Papini, Maggiani 2023a

M. Papini, A. Maggiani, Statua di togato forse dal territorio perugino, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 56-59. - Papini, Maggiani 2023b

M. Papini, A. Maggiani, Ritratto maschile con dedica al Flere di Havens, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 104-107. - Pardini 2023

G. Pardini, Le offerte di moneta nella vasca. Questioni preliminari e prospettive di ricerca, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, 255-267. - Pardini, Carbone 2023

G. Pardini, F. Carbone, I rinvenimenti monetali, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, pp. 148-155. - Salvi 2023a

A. Salvi, Nascita e rinascita: l’infanzia nella vasca sacra attraverso le offerte in bronzo, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli, 137-151. - Salvi 2023b

A. Salvi, Ex voto in bronzo da Buca delle Fate, santuario termale di Campo Muri, Rapolano Terme (SI), in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 50-55. - Salvi 2023c

A. Salvi, Tre elmi a maschera da Le Querciolaie, Rapolano Terme (SI), in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 62-65. - Salvi, Tabolli 2022

A. Salvi, J. Tabolli, L’economia del sacro e le sorgenti termali di Campo Muri (Rapolano Terme, SI). Nuove indagini sul deposito votivo di Buca delle Fate, in M.C. Biella, C. Carlucci, L.M. Michetti (a cura di), Produrre per gli Dei. L’economia per il sacro nell’Italia preromana (VII-II sec. a.C.), Atti del Workshop internazionale (Roma, 7-8 ottobre 2021), “ScAnt” XXVIII, 2 (2022), 527-537. - Sannibale 2018

M. Sannibale, Il crescente lunare con dedica a Tiur gia collezione Borgia (CII 2610 bis), “StEtr” LXXXI (2018), 253-264. - Sannibale 2018-2019

M. Sannibale, Il crescente lunare con dedica etrusca a Tiur gia collezione Borgia, “RendPontAc” XCI (2018-2019), 169-207. - Sannibale 2023

M. Sannibale, Crescente lunare già Collezione Borgia, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 48-49. - Tabolli 2023a

J. Tabolli, The Etrusco-Roman thermo-mineral sanctuary of Bagno Grande at San Casciano dei Bagni (Siena): aims and perspectives ‘behind-the-scenes’ of the ongoing multidisciplinary research project, “FOLD&R” DLVI (2023c), 1-23. - Tabolli 2023b

J. Tabolli, Tra divinazione e medicina termale, in Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, 235-247. - Tabolli 2023c

J. Tabolli, Uno sguardo sul territorio di San Casciano dei Bagni lungo due millenni, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 11-15. - Tabolli, Gregori 2023

J. Tabolli. G.L. Gregori, Tra corpi di bronzo, strumenti chirurgici e medicina termale, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 98-103. - Tabolli, Maggiani 2023

J. Tabolli, A. Maggiani, Il putto di San Casciano dei bagni, in Osanna, Tabolli 2023, 120-123. - Wylin 2001

K. Wylin, Scheda epigrafica, “Studi etruschi” LXIV 1998 (2001), 447-449.

Abstract

This paper presents a general overview on the display of the Bronzes of San Casciano dei Bagni the on-going exhibition at Palazzo del Quirinale. It especially focuses on the ancient multiculturalism and multilingualism that characterized the Etruscan and Roman sanctuary of Bagno Grande as it appears in the inscription on the statues and statuettes. Moreover, this paper discusses the parallel narratives of the excavation and of the exhibition in order to stress the complexities as well as the potentialities of this archaeological context in order to unlock an ancient sacred site with its landscape.

keywords | San Casciano dei Bagni; Etruscan and Roman Bronzes; sanctuary; ancient medicine.

All contributions to this issue of Engramma have followed invited submission and have been reviewed by the editorial board and scientific committee of the journal

To cite this article: Jacopo Tabolli, Digging into a Display. The ‘Voices’ of the Bronzes from San Casciano dei Bagni, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 204, luglio/agosto 2023, pp. 175-191 | PDF of the article