Healing Perception and Ritual Practice through the Metal Gifts in the Hot Water at San Casciano dei Bagni

Mattia Bischeri

Abstract

The thermo-mineral sanctuary at Bagno Grande, in San Casciano dei Bagni, offers an extraordinary amount of data for the analysis of the healing cults and thermal medicine (Tabolli 2023, 9-11; Tabolli 2023a), in the context of multicultural interaction among Etruscans and Romans (Tabolli 2023, 6-8). In ancient societies, ritual healing practices and practical medicine, including the thermal medicine and balneotherapy, are strictly entangled. The votive record of Bagno Grande allows us to explore some issues of ancient medical practices, in particular, those regarding the experiential dynamics of the healing cult and the implications from a cognitive perspective. In the last few years, the study of the religious experience of the past, especially by the ‘Lived Ancient Religion’ approach (Gasparini et alii 2020; Graham 2021), has concerned the interplay between sensory, cognitive and socio-cultural aspects, as well as the negotiation between the individual and group agents. Furthermore, the cognitive perspective in archaeology, influenced by neuro-science and evolutionary psychology, has explored the forms of dependence between social and cultural behaviour and things (Hodder [2012] 2014). In this paper, adopting a cognitive approach and following the perspectives of Medical Anthropology, I aim to untangle the aspects of the worshipper’s perception of healing through the materiality of the votive gifts in the sanctuary at Bagno Grande.

Archaeological context and cult practices

1 | Map of mayor building phases and the view on the thermo-mineral sanctuary at Bagno Grande, San Casciano dei Bagni (edited by E. Mariotti).

2 | Series of bronze statues depicting divinatory gestures 3rd – 1st centurt BC: a. Bagno Grande (San Casciano dei Bagni); b. Bagno Grande (San Casciano dei Bagni); c. San Faustino (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Perugia); d. ‘Putto Graziani’ (Museo Gregoriano Etrusco); e. Vulci, Porta Nord (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia); f. Putto from Montecchio, Cortona (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden); g. Kelebe from Perugia (Maggiani 2002).

The ongoing excavations at Bagno Grande, immediately below the Medici’s thermal structure, continue to illuminate the extent of building during the Etruscan and Roman phases, focused on a narrow structure with a monumental central pool and its intact votive deposit within [Fig. 1]. The structure saw a period of continuity and change over at least 700 years between the 3rd century BC and the 4th century AD, when the sanctuary was intentionally dismantled, perhaps after the Edict of Theodosius against the pagan religion. The portion discovered thus far is to be considered the core of a vaster spring sanctuary, with a monumental architecture meant to protect and sacralise the hot spring of Montesanto, that continues to flow at a rate of 25 liters of water per second at over 40 degrees C. Before the decommission of the sanctuary in the Late Antique phase, the building and the central pool had been restored many times. Underneath the Roman phase, is coming to light the Etruscan one, represented by a rectangular enclosure in travertine and an earlier pool, partially conserved with an oval shape. A turning point in the stratigraphical sequence is marked by a glimpse of the Tiberian age, when the deepest Etruscan oval pool was ritually closed and abandoned. All the statues exhibited in the sanctuary, belonging to late Etruscan and early Roman phases, were collected and buried in the pool below a thick layer of roof tiles. A bronze thunderbolt among the tiles, put in as a seal, together with two prehistoric flint arrowheads, suggest that the rite operated was a fulmen condere (MacIntosh Turfa 2012, 59-60). After this event and the new monumental phase, the pool received new votive offerings, including thousands of coins, that continued several centuries beyond the Severan age (Mariotti 2023; Mariotti, Carpentiero 2023; Tabolli 2023b; Tabolli 2023, 1-6).

The principal votive gifts are represented by large bronze statues (Papini 2023), figurines of human or animal shape (Salvi 2023; Bischeri 2023; Arbeid 2023), anatomical ex-votos (De Lucia Brolli 2023; Pacifici 2023) – sometimes bearing Etruscan or Roman inscriptions (Maggiani 2023; Gregori 2023) –, coins (Pardini 2023), stone altars (Gregori 2022), and vegetal offerings (Buonincontri 2023). Beyond the main deities that were protecting the spring, connected to the power of healing – Fortuna Primigenia and Apollo, Asclepius, Hygea and Isis – an additional god/goddess, directly referred to the Nymph of the same thermo-mineral hot spring, is attested in two different languages: Flere of Havens (the goddess of the spring or the hot spring), the Etruscan name (Maggiani 2023), and Fons caldus (the hot spring), in Latin (Gregori 2023). An exceptional stone base-altar bearing a bilingual inscription confirms the sanctuary's multicultural framework, which includes Etruscans and Romans together (Tabolli 2024).

Despite the transformations through the centuries, the cult always focused on the hot spring as an element of prediction and healing benefits simultaneously. The archaeological evidence suggests that the practice of thermal medicine was related to the divinatory art concerning the natural elements (Tabolli 2023a). In fact, the natural phenomenon of the spring represents a pivotal element at Bagno Grande. The spring of Montesanto is characterised by specific physico-chemical characteristics, empirically perceived, such as the high temperatures, and the emission of vapor and bubbles. Natural events can influence the perceived characteristics of the water at any time, changing the level and temperature, as is demonstrated by the ongoing hydrogeological analysis of the spring (Tabolli 2023a, 235 notes 1-2; Tabolli 2023, 8). The reading of natural evidence and subtle related changes to the environment could be interpreted as predictable signs of divine will (auspicium) in the perception of the ancient priest; this facet of divinatory practice is a key feature of Etruscan religion (ThesCRA III; De Grummond, Simon 2006; MacIntosh Turfa 2012; Capdeville 2016). The divinatory art, particularly that which is connected to the observation of birds, is emphasised by some bronze statues depicting youths raising a small bird with the right hand, and holding a fruit with the left hand. These statues belong to a broad type of Etruscan bronzes dated between the 3rd and 1st century BC, which depicts youths and babies in different moments of the completion of a rite, step by step, from the observation of the flight, to the request of augurium or to gain auspicium, and, finally, to the acquisition of a response [Fig. 2]. This gesture is interpreted as augural or divinatory, according to the Etruscan-origin interpretation practice of the observation of a bird’s flight and appetite (Bischeri 2023, 159). It’s a matter of fact that the bird’s behaviour, in particular feeding, could be influenced by changes in barometric pressure and weather (Tuck 2020). Additionally, the statues’ attributes of the bird and fruit, could be connected to the rites of passage from infancy to personhood (Turchetti et alii 2023, 119-120).

The practice of thermal medicine, related to the healing cult of sanatio (Comella 1981; Comella, Mele 2005; Fabbri 2019), is attested by a long series of ex-votos, particularly the anatomical types [Fig. 3]. The hot water, enriched by mineral sulfates, used for bathing but not for drinking, can produce physiological benefits for the health of the body, with anti-inflammatory and disinfectant effects. The anatomical ex-votos, in fact, depict limbs and external organs, such as arms, legs, feet, ears, eyes, and breasts (De Lucia Brolli 2023; Pacifici 2023). Beyond these specimens, there are also some internal organs, and in particular, two exceptional bronze plaques with polyvisceral reliefs. One of them has been assembled on a base that bears a dedicatory inscription in Latin of a healing request for a Roman woman, Sulpicia Triaria, to Fortuna Primigenia.

The reliefs display viscera as they would appear in a human torso opened with a laparotomic cut. A medical instrument, a bronze gouge, was also collected in the votive deposit. These specimens of polyvisceral reliefs, which, until now, we have only seen in pottery replicas, testify to a very advanced knowledge of medical practices, as well as to the presence of doctors who likely performed operations and other surgical interventions at the site (Tabolli 2023a).

Theoretical issues in perception and practice of the healing cults

3 | From Bagno Grande: a. Anatomical ex-votos; b. Polyvisceral relief; c. Bronze gouge (after Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, edited by M. Bischeri).

4 | Christian healing cults: a. Sanctuary of Romituzzo at Poggibonsi, Siena; b. Sanctuary of Madonna del Bagno at Deruta, Perugia; c. Sanctuary of Madonna della Quercia at Viterbo (edited by M. Bischeri).

In traditional societies, practical medicine and ritual healing practices are firmly connected, and found the perfect synthesis in thermal sanctuaries, where water simultaneously could be a tool of healing and an object of cult (Facchinetti 2010). The religious phenomenon of healing cults is shared in the gamut of global religious experiences beyond religious belief. It is based on similar perceptive, psychological and sociological dynamics throughout time. Behind the perspective of the devotees, the main cognitive and psychological aspect can be considered the ‘faith-healing’, namely the faith in the therapeutic efficacy of the cult felt by the individual worshipper, as theorized by J.-M. Charcot at the end of 19th century (Charcot [1892] 2019). The sociological aspect concerns the ‘sense of communitas’, namely the general perception by the community of worshippers and the sense of belonging to a religious phenomenon, that originates the rules of performative actions and the pilgrimage toward a sacred place as pointed out by V. Turner (Turner 1969).

The action on the mind is considered a pivotal aspect of the functioning of the healing cults, beyond any ‘miraculous’ belief. In the field of Medical Anthropology, it is understood that the body, with practical interventions and physiological reactions, and the mind, with cognitive interventions and psychological reactions, are entangled in the process of healing. After the French scholars Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Pierre Bordieu figured out the concepts of ‘Perception’ (Merleau-Ponty [1945] 2021) and ‘Practice’ (Bordieu [1972] 2003), American anthropologist Thomas Csordas founded his paradigms of ‘Embodiment’, in which the body is considered the “existential ground of culture and self” (Csordas 1994; Id. 1999). In several studies focusing on the ritual healing and meaning of the Charismatic cult, Csordas overcomes the Cartesian paradigm that is stuck between the ‘body’ and ‘mind’ dichotomy; instead, he adopts a holistic perspective that better parallels traditional curing systems (Csordas 2002). Under this perspective, the religious phenomenon takes place in the body together with its sensorial abilities and corporeal cognition; the body and its functions encompass the goods and needs that the gods are made for. “Illnesses and malfunctions of the body are recurring reasons for addressing the gods, but are also a means by which humans can come closer to their deities” (Rieger 2020, 202-203; Gasparini 2023, 386-388). In ritual curing and healing systems, the state of illness is not limited to purely biological processes, as is conceived by modern biomedicine, but spiritual and social factors are also important causes of it. Overcoming the state of illness occurs through practices that are both empirically and symbolically effective: technical interventions (i.e. the use of drugs and surgical intervention) cure the body, and symbolic rites (i.e. rites and prayers) heal the mind (Lionetti 1988; Young [1982] 2006; Cozzi 2012). Supporting the ritual efficacy idea, Claude Levi-Strauss has introduced the concept of ‘symbolic efficacy’ of rituals (Lévi-Strauss [1949] 2015, 210-230), which can be related to the concept of ‘meaning response’ of Daniel Moerman (Moerman 2002). The agency of symbols behind the mythic form performed by the rituals, transforms the mind on an unconscious level creating a comprehension of the situation and a concrete experience of healing (Langdon 2007). The performative aspect of ritual in some traditional curing systems, based on dedications of particularly meaningful objects in a sacred place, represents the material support of the healing process. The sacred gifts can activate cognitive and emotional processes that result in actual physiological reactions. In psychoneuroimmunology, these physiological reactions are related to the production of endorphins that commonly have analgesic, euphoric, and amnesic effects helpful for managing sickness and disease (Lupo 2012, 148-155). From this point of view, the ex-votos, as ritual objects dedicated before a healing request or as thanks for the healing received, play a concrete role in constructing a collective perception of therapeutic efficacy (Graham, Draycott 2017), and represent instruments of religious knowledge (Graham 2020, 211). If humans depend on things, the symbolic agency behind sacred objects can feed the mind and shape how social actors see, feel, and think about the sacred being (Fabietti 2014).

Similar dynamics are evidenced by Catholic Marian cults which generally encompass faith healing. The symbolic efficacy of the cult is fed and improved by a community of pilgrims offering votive gifts after a healing request [Fig. 4]. Significant examples in Italy include the Sanctuary of Romituzzo at Poggibonsi near Siena (Valdelsa 2000, 95-96), the Sanctuary of Madonna del Bagno at Deruta near Perugia (Santantoni Menichelli 2010), and the Sanctuary of Madonna della Quercia at Viterbo (Carosi, Ciprini 1992). Water and mineral springs often are pivotal aspects, as exemplified also by the famous Lourdes ritual bath. These types of traditional Catholic cults, particularly their rituals and beliefs, are rooted in long-standing pagan cults, as is demonstrated for instance by the galactophoric cults ranging from the Egyptian Isis ‘Mother of God’ to the iconography of Maria lactans (Basta 2023). Regarding this particular aspect, further examples include some natural caves in Italy which were the setting of ancient cults. In the Grotta Lattaia at Cetona, late Etruscan pottery ex-votos of breasts and statues of infants testify to the enduring belief in the beneficial properties of breastfeeding expressed by drinking the water dripping from natural stalactites.

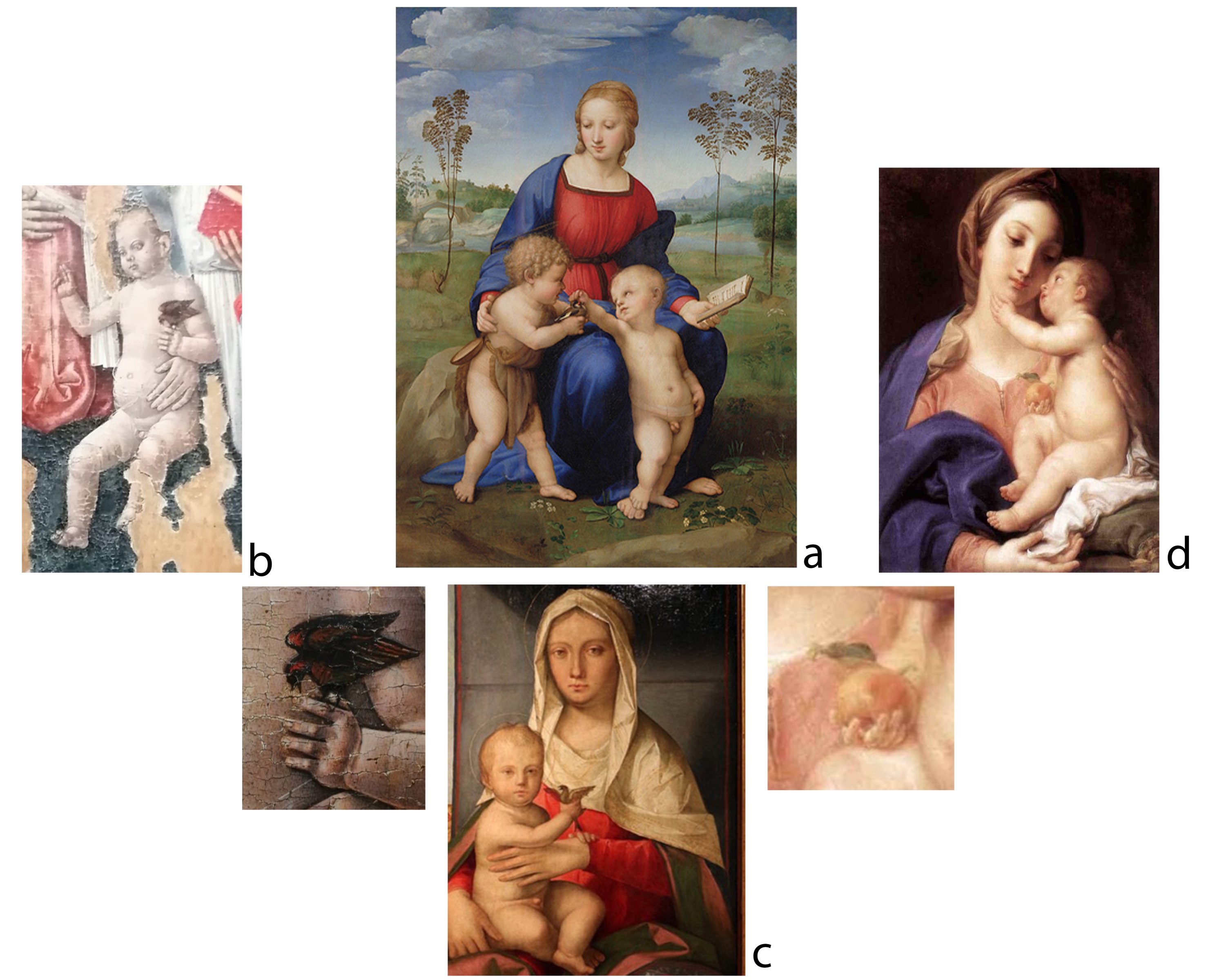

The continuity of the cult, still venerated in the Christian era, is demonstrated also by the veneration of motherhood related to the Madonna lactans as depicted in the sanctuary of Santa Maria in Belverde (Turchetti et alii 2023). When constructing cult efficacy, iconographic and symbolic patterns also play a key-role. Christian symbols and allegories sometimes retain pagan iconographic style and can preserve traces of their symbolic efficacy, adapting syncretistically to different visual cultures (Elsner 2003, 117-118). As seen before for the iconography of the Isis ‘Mother of God’ and Maria lactans, the thousands of depictions of Mary and Jesus are relevant too [Fig. 5], where the baby Jesus often holds a bird in one hand and a fruit in other, as in the most famous, Raffaello’s model of the Madonna del Cardellino (Amato 1988; Torchio 2023, 55). The model of a baby with that particular gesture of presenting a fruit to a bird already appears in ancient sacred iconography across the Mediterranean, from the tradition of the crouching children and ‘temple boys’ (Hadzisteliou-Price 1969) and classical Greek reliefs (Comella 2002, 144, fig. 146), to Roman depictions (Conticello 1993, 294-296, n. 227), to several Coptic funerary stelae (Wessel 1969, 103; Morehouse 2024, 121-134). Arguably, the iconography of the Etruscan votive babies of the 3rd-1st c. BC seen above, as a depiction of a divinatory gesture of augurium or auspicium, might recall the acquisition of the Holy Spirit in Christian belief, symbolically depicted as a bird.

Materiality and perception of healing at Bagno Grande

5 | Sacred depictions with Mary and Baby Jesus: a. Raffaello Sanzio, Madonna del Cardellino, oil on canvas, 1506, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; b. Girolamo di Benvenuto, Madonna con bambino in trono tra i Santi Giacomo e Andrea, XVI c., tempera on canvas, Museo dell’Opera della Cattedrale di Chiusi; c. Boccaccio Boccaccino, Madonna col Bambino, oil on canvas, 1525, Pinacoteca Egidio-Martini, Venice; d. Pompeo Batoni, Madonna e Bambino, oil on canvas, 1742, Galleria Borghese, Rome (edited by M. Bischeri).

The persistent continuity of worship at Bagno Grande coupled with the monumentality of the sanctuary and the quality of its votive offerings, represents significant elements of analysis that suggest how the community of worshippers may have perceived a high level of therapeutic effectiveness (physiological and psychological) within the cult of the hot spring.

The materiality of the offerings, as sacred objects able to activate a positive symbolic agency in the mind of the devotees, is connected to the raw materials from which the ex-votos are made. Concerning the broad examples of figural bronzes, the healing perception behind the dedication of the ex-votos and their symbolic values were undoubtedly entangled with the economic value of the metal itself (Bischeri 2023). Sampling the size and weight of the bronzes from a metrological perspective, we can see some impressive correlations between their heights and the multiples and submultiples of the Roman foot, as well as their weights and the Roman libra. The scale of the offering’s heights includes figurines that range from 7 to 30 cm, and larger statues that measure up to 90 cm. Ninety cm corresponds to 3 Roman feet, the measure indicated by the Latin writers as mensura honorata, namely the correct measurement for statues dedicated in the Roman forum. Furthermore, the ponderal values of the statues correspond with the monetary system that was in use between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC. Based on the request for healing and the gift of a suitable measure of metal, the bidding system of the thermal sanctuary of Bagno Grande appears to have been a genuine economic hub, with bronze offerings placed under divine protection, functioning as a trading contract between humans and deities. In the Roman phase, in fact, the offerings of varied metal gifts were eventually replaced by offerings of coins.

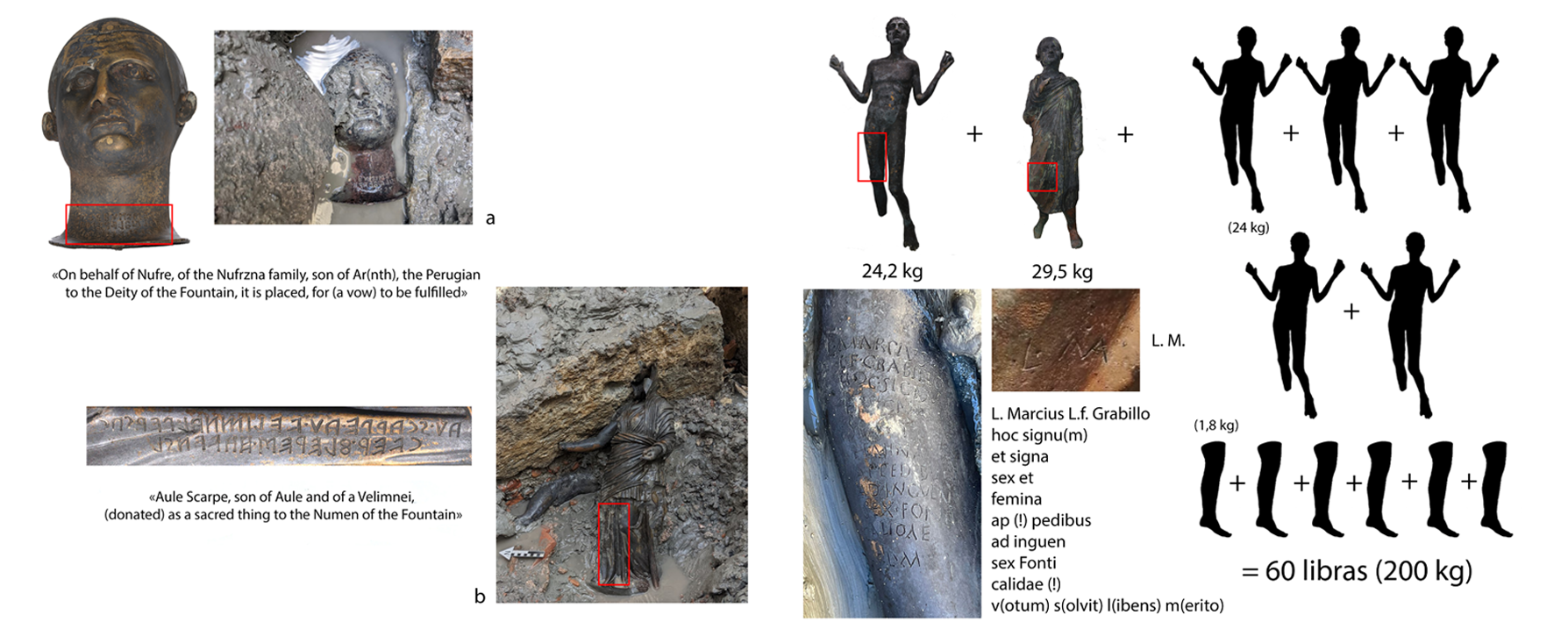

The bronze statues represent the support on which the worshipper’s identity is inscribed too. Despite the heroic nudity typical of ancient statuary, the bronze body can materialise the state of the worshipper’s disease. One statue, in fact, depicts a male with a malformed body: the chest is gaunt, the abdomen is rounded, the shoulders are asymmetric and so on. The representation of the devotee’s health condition is intentional [Fig. 6].

Along the left leg runs a Latin inscription that mentions the name of dedicant, Marcius Grabillo, and the spring’s goddess, Fons calidae. Requesting healing, Grabillo fulfilled his vow (votum solvit), by dedicating a bronze image of himself of about 24 kg of bronze. The inscription also mentions the entirety of Grabillo’s gift to the god: beyond this statue, he dedicated six statues (signa) and six lower limbs (femina appedibus ad inguem), perhaps anatomical ex-votos. Suppose we imagine the other offerings were similar in scale to the extant specimens: in that case, we can calculate the amount of bronze at approximately 60 Roman libras (200 kg) dedicated by Grabillo to the hot spring.

In the Etruscan and Roman dedication formulas on the ex-votos, a fundamental aspect seems to be the indication of the worshipper’s origin and family name [Fig. 7]. The expression of the individual identity could play a primary role in the collective perception of the healing cult. For instance, the bronze portrait with an Etruscan inscription that includes the name of the man making the offering, Nufre of the Nufrzna family, comes from the Etruscan city-state of Perusia, about 50 km from Clusium, as suggested by the ethnic adjective Persac (‘the Perusian’). The bronze female statue, wearing a crown in the form of a turreted diadem with a snake rolled up on the arm, probably depicts the goddess of the spring, as the inscription dedicated to Flere of Havens suggests. The dedicator of this statue, Aule Scarpe, is kindred with the Velimna family, one of the most powerful families in Perusia between the 3rd and 1st century BC (Maggiani 2023, 182-189).

6 | Bronze nude statue dedicated by M. Grabillo and togato statue, San Casciano dei Bagni, with hypothesis of the amount of bronze dedicated by himself according to the Latin inscription (after Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, edited by M. Bischeri).

7 | Bronze votive head dedicated by Nufre and female bronze statue dedicated by Aule Scarpe, San Casciano dei Bagni (after Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023, edited by M. Bischeri).

Additionally, a non-secondary perceptive element would be represented also by the fame of the Fontes clusini in the ancient times, well-known by Etruscans and Romans for their therapeutic properties to cure head and stomach diseases, as mentioned by the Latin writer Horace (Hor. ep. I, 15). The echo of the fame perhaps generated a further rhetoric of persuasion around the curative efficacy of the Aquae clusinae, with a growth of a positive response to receive the healing in the individual’s perception, as well as a collective resonance in the community of the worshippers activating a flow of different peoples toward the clusine area.

The votive offerings must be understood as tangible signs that the worshippers entrusted a part of themselves to the care of the divine, and believed that the divine had the power to offer healing or that the divine reciprocated. The materiality of the vow seems to play a pivotal role in the cognitive perception of healing, especially in a sacred place where the symbols related to the materiality of ritual gifts, shaping human minds, work together with empirically effective medical practices, shaping the bodies. Let us imagine the sanctuary at Bagno Grande before the Tiberian restoration and the ritual burial of the votive offerings within the pool, how the sacred landscape around the natural hot spring, enriched by hundreds of sacred bronze gifts offered by illustrious Latin and Etruscan worshippers, such as Grabillo or Nufre, together contributed to the empowerment of the healing properties of the hot spring deity with a visual confrontation with the body of the combined religious community (Graham 2017, 53-54), making the sanctuary at Bagno Grande one of the most attractive healing sanctuaries in central Italy.

Bibliography

- ThesCRA

Thesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum, publié par la Fondation pur le Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, Los Angeles 2004. - Amato 1988

P. Amato (a cura di), Imago Mariae. Tesori d’arte della civiltà cristiana, Catalogo della mostra (Roma, 20 giugno – 2 ottobre 1988), Roma 1988. - Arbeid 2023

B. Arbeid, I piccoli animali in bronzo: indizi di un’assenza, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 167-179. - Basta 2023

C. Basta, Dalla dea madre alla Madonna del Latte: una lunga storia di cura, in Turchetti, Lasci 2023, 135-141. - Bischeri 2023

M. Bischeri, La giusta misura. Bronzetti a figura umana e valori metrologici, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 153-165. - Bordieu [1972] 2003

P. Bordieu, Per una teoria della pratica, Milano [1972] 2003. - Buonincontri 2023

M. Buonincontri, Offerte in legno e frutti: novità e conferme nella sacralità etrusca e romana, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 279-289. - Carosi, Ciprini 1992

A. Carosi, G. Ciprini, Gli ex voto del santuario della Madonna della Quercia di Viterbo. Immagini e testimonianze di fede, Viterbo 1992. - Capdeville 2016

G. Capdeville, L’uccello nella divinazione in Italia centrale, in A. Ancillotti, A. Calderini, R. Massarelli (a cura di), Forme e strutture della religione nell’Italia mediana antica, III Convegno Internazionale dell’Istituto di Ricerche e Documentazione sugli Antichi Umbri (Perugia, 21-25 settembre 2011), Roma 2016, 79-154. - Charcot [1892] 2019

J.-M. Charcot, La fede che guarisce, edizione italiana a cura di T. Seppilli e Y.O. Celso, Pisa 2019 [1892]. - Csordas 1994

T.J. Csordas (ed.), Embodiment and experience. The existential ground of culture and self, Cambridge 1994. - Csordas 1999

T.J. Csordas, Embodiment and cultural phenomenology, in G. Weissm, F.H. Haber (eds.), Perpectives on embodiment. The intersection of nature and culture, London 1999, 143-162. - Csordas 2002

T.J. Csordas, Body/Meaning/Healing, New York 2002. - Comella 1981

A. Comella, Tipologia e diffusione dei complessi votivi in Italia in epoca medio- e tardo-repubblicana. Contributo alla storia dell’artigianato antico, “MEFRA” 93 (1981), 717-803. - Comella 2002

A. Comella, I rilievi votivi greci di periodo arcaico e classico: diffusione, ideologia, committenza, Bari 2002. - Comella, Mele 2005

A. Comella, A. Mele (a cura di), Depositi votivi e culti dell’Italia antica dal periodo arcaico a quello tardo-repubblicano, Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Perugia 2000), Bari. - Conticello 1993

B. Conticello (a cura di), Riscoprire Pompei, Catalogo della mostra (Roma 13 novembre 1993-12 febbraio 1994), Roma 1993. - Cozzi 2012

D. Cozzi (a cura di), Le parole dell’antropologia medica. Piccolo dizionario, Perugia 2012. - De Grummond, Simon 2006

N. De Grummond, E. Simon (eds.), The religion of the Etruscans, Austin 2006. - De Lucia Brolli 2023

A.M. De Lucia Brolli, Le maschere. Il volto e lo sguardo nelle lamine, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 223-233. - Elsner 2003

J. Elsner, Archaeologies and Agendas: Reflections on Late Ancient Jewish Art and Early Christian Art, “The Journal of Roman Studies” 93 (2003), 114-128. - Fabietti 2014

U. Fabietti, Materia sacra. Corpi, oggetti, immagini, feticci nella pratica religiosa, Milano 2014. - Fabbri 2019

F. Fabbri, Votivi anatomici fittili. Uno straordinario fenomeno di religiosità popolare dell’Italia antica, Bologna 2019. - Facchinetti 2010

G. Facchinetti, Offrire nelle acque: bacini e altre strutture artificiali, in H. Di Giuseppe, M. Serlorenzi (a cura di), I riti del costruire nelle acque violate, Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Roma, 12-14 giugno 2008), Roma 2010, 43-67. - Gasparini 2023

V. Gasparini, Risonanza somatica, ovvero il corpo rituale come strategia di ottimizzazione del potere divino. Vestigia e Ohrenweihungen, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 358-393. - Gasparini et alii 2020

V. Gasparini, M. Patzelt, R. Raja, A.-K. Rieger, J. Rüpke and E. Rubens Urciuoli (eds.), Lived Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Approaching religious transformations from archaeology, history and classics, Berlin/Boston 2020. - Graham 2017

E.-J. Graham, Partible humans and permeable gods. Anatomical votives and personhood in the sanctuaries of central Italy, in Graham, Draycott 2017, 45-62. - Graham 2020

E.-J. Graham, Hand in hand: rethinking anatomical votives as material things, in Gasparini et alii 2020, 209-235. - Graham 2021

E.-J. Graham, Reassembling religion in Roman Italy, New York 2021. - Graham, Draycott 2017

E.-J. Graham, J. Draycott, Debating the anatomical votive, in J. Draycott, E.-J. Graham, Bodies of Evidence. Ancient Anatomical Votives. Past, Present and Future, London-New York 2017, 1-19. - Gregori 2022

G.L. Gregori, Una famiglia senatoria del tardo II secolo d.C.: le nuove iscrizioni dal Bagno Grande, in E. Mariotti, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Il Santuario ritrovato 1. Nuovi scavi e ricerche al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2022, pp. 193-199. - Gregori 2023

G.L. Gregori, Iscrizioni latine su votivi in bronzo: divinità, devoti, formulari, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 195-203. - Hadzisteliou-Price 1969

T. Hadzisteliou-Price, The Type of the Crouching Child and the 'Temple Boys', “The Annual of the British School at Athens” 64 (1969), 95-111. - Hodder [2012] 2014

I. Hodder, Entangled. An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things, Singapore 2014 [2012]. - Langdon 2007

E.J.M. Langdon, The Symbolic Efficacy of Rituals: From Ritual to Performance, “Antropologia em Primeira Mão” 95 (2007), 5-40. - Lévi-Strauss [1949] 2015

C. Lévi-Strauss, Antropologia strutturale, Milano 2015. - Lionetti 1988

R. Lionetti, L’efficacia terapeutica: un problema antropologico, “La ricerca folklorica” 17 (1988), 3-6. - Lupo 2012

A. Lupo, Malattia ed efficacia terapeutica, in Cozzi 2012, 127-155. - Lupo 2014

A. Lupo, Antropologia medica e umanizzazione delle cure, “Rivista della Società italiana di antropologia medica” 37 (2014), pp. 105-126. - Maggiani 2002

A. Maggiani, I culti di Perugia e del suo territorio, in G.M. Della Fina (a cura di), Perugia etrusca, Atti del IX Convegno Internazionale di Studi sulla Storia e l’Archeologia dell’Etruria (Orvieto 2001), 267-299. - Maggiani 2023

A. Maggiani, Le iscrizioni etrusche su votivi di bronzo. La divinità e i suoi devoti, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 181-193. - Mariotti 2023

E. Mariotti, Il Bagno Grande nelle campagne di scavo 2021 e 2022, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 29-47. - Mariotti, Carpentiero 2023

E. Mariotti, G. Carpentiero, Dal sottosuolo agli elevati: l’architettura del santuario, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 49-61. - Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023

E. Mariotti, J. Tabolli, A. Salvi, Il Santuario ritrovato 2. Dentro la vasca sacra. Rapporto preliminare di scavo al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2023. - MacIntosh Turfa 2012

J. MacIntosh Turfa, Divining the Etruscan World: the Brontoscopic Calendar and Religious Practice, Cambridge 2012. - Merleau-Ponty [1945] 2021

M. Merleau-Ponty, Fenomenologia della percezione, Milano [1945] 2021. - Moerman 2002

D.E. Moerman, Meaning, medicine and the ‘placebo effect’, Cambridge 2002. - Morehouse 2024

L.R. Morehouse, Recontextualizing the boy with grapes stelae of Roman Egypt: Authenticity, connectivity, and memory, PhD thesis, fully internal, Universiteit van Amsterdam 2024. - Pacifici 2023

M. Pacifici, Per grazia ricevuta. Il sistema degli ex voto anatomici in metallo, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 205-221. - Papini 2023

M. Papini, Immagini di divinità e devoti in bronzo, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 117-135. - Pardini 2023

G. Pardini, Le offerte di moneta nella vasca. Questioni preliminari e prospettive di ricerca, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 255-267. - Rieger 2020

A.-K. Rieger, Introduction to Section 2, in Gasparini et alii 2020, 201-208. - Salvi 2023

A. Salvi, Nascita e rinascita: l’infanzia nella vasca sacra attraverso le offerte in bronzo, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 137-151. - Santantoni Menichelli 2010

A. Santantoni Menichelli (a cura di), Ex voto. Arte e fede nel Santuario della Madonna del Bagno in Casalina, Perugia 2010. - Tabolli 2023

J. Tabolli, The Etrusco-Roman thermo-mineral sanctuary of Bagno Grande at San Casciano dei Bagni (Siena): aims and perspectives ‘behind-the-scenes’ of ongoing multidisciplinary research project, “FOLDER-it” 556 (2023). - Tabolli 2023a

J. Tabolli, Tra divinazione e medicina termale, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 235-247. - Tabolli 2023b

J. Tabolli, Dentro la vasca sacra, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 101-115. - Tabolli 2024

J. Tabolli, Un donario e un’iscrizione bilingue, in M. Osanna, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Gli dei ritornano. I bronzi di San Casciano, Catalogo della mostra (Napoli 2024), Roma 2024, 157-158. - Torchio 2023

F. Torchio, La venerata immagine della Madonna col bambino, in Itinera ad loca mariana II. Il Monte Amiata, Sinalunga 2023, 55. - Tuck 2020

A. Tuck, Augury and Observation: Speculations on the Nature of an Ancient Italic Ritual Practice, “Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome” 65 (2020), 540-557. - Turchetti, Lasci 2023

M.A. Turchetti, E. Laschi (a cura di), La Via Lattea. Maternità e infanzia dall’antichità alla collezione Bellucci, Catalogo della mostra (Perugia 20 dicembre 2022 – 30 settembre 2023), Perugia 2023. - Turchetti et alii 2023

M.A. Turchetti, M.T. Cuda, E. Laschi, D. Nati, Grotta Lattaia e il culto del latte, in Turchetti, Lasci 2023, 111-127. - Turner 1969

V. Turner, The ritual process. Structure and anti-structure, Ithaca/New York 1969. - Young [1972] 2006

A. Young, Antropologie della “illness” e della “sickness”, in I. Quaranta (a cura di), Antropologia medica. I testi fondamentali, Milano [1972] 2006, 107-147. - Valdelsa 2000

Il Chianti e la Valdelsa senese, Milano 2000. - Wessel 1969

K. Wessel, Koptische kunst. Die Spätantike in Ägypten, Recklinghausen 1969.

The thermo-mineral sanctuary at Bagno Grande in San Casciano dei Bagni (province of Siena, central Italy) offers extraordinary data for the analysis of healing cults and thermal medicine in the context of multicultural interaction among Etruscans and Romans. The core of the sanctuary is a sacred pool meant to protect and sacralise a hot spring, which contains an intact votive deposit stratified by several phases of large statues, bronze figurines, anatomical ex-votos, thousands of coins, stone altars, and vegetal offerings. Throughout time, from at least the 3rd century BC to the 4th century AD the cult associated with the sacred pool has maintained its focus on the hot spring recognizing it as a pivotal natural element of prediction and healing simultaneously. In this paper, adopting a cognitive approach and the perspectives of Medical Anthropology, I seek to focus on the agency of the votive offerings on the perception of the worshippers.

keywords | Thermal sanctuary; ex-votos; Medical anthropology; cognitive approach.

questo numero di Engramma è a invito: la revisione dei saggi è stata affidata al comitato editoriale e all'international advisory board della rivista

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: M. Bischeri, Healing Perception and Ritual Practice through the Metal Gifts in the Hot Water at San Casciano dei Bagni, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 214, luglio 2024, 25-42 | PDF