Offering truncated bodies in Roman Gaul

Layouts, antecedents and interpretations

Olivier de Cazanove

Abstract

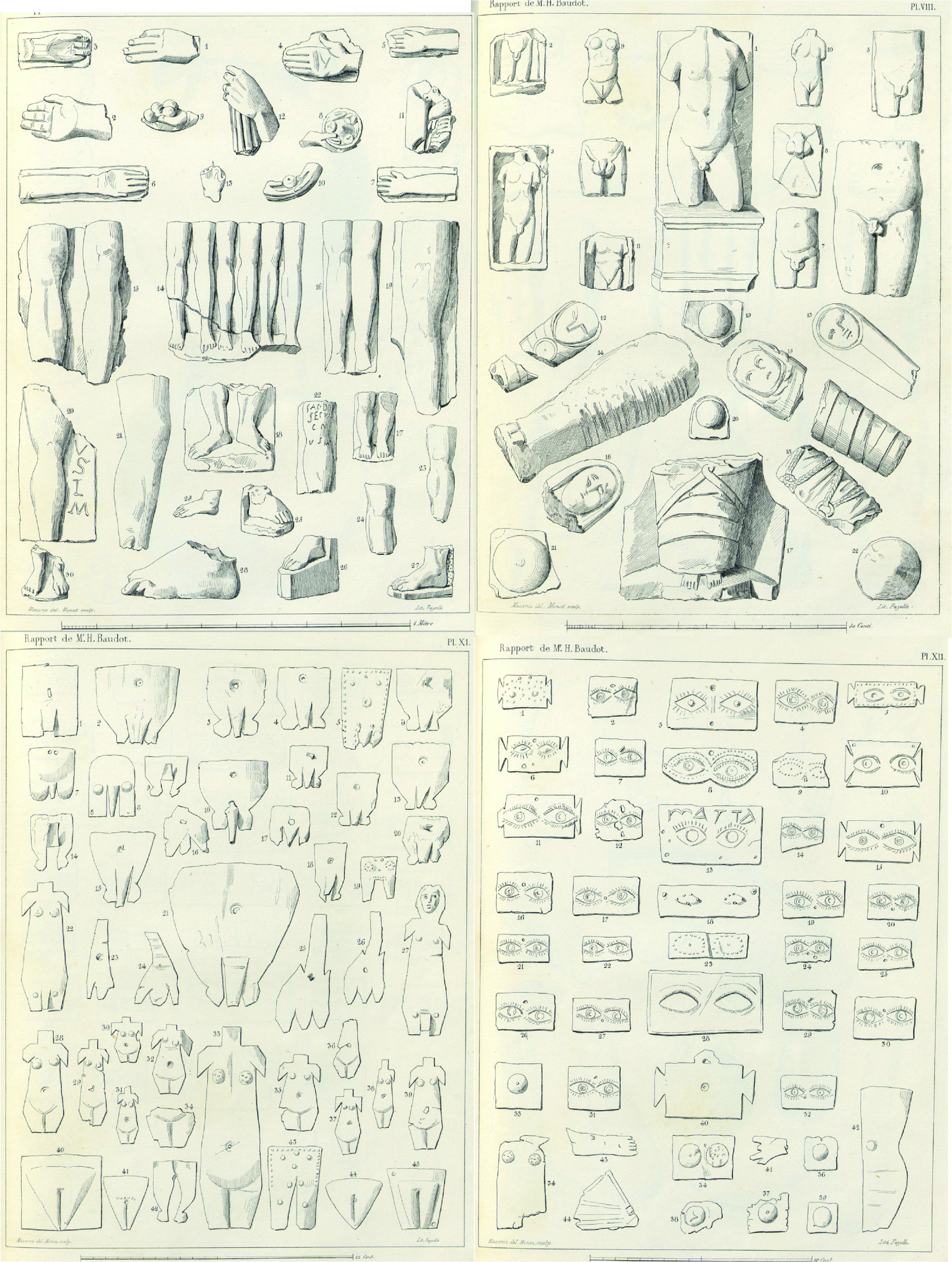

1 | Four plates from the original publication by Baudot of his excavations at the sanctuary of Sequana next to the Seine Springs (Baudot 1842-1846).

The anatomical offerings of Central Italy are certainly those that enjoy the greatest notoriety today, due to their huge quantity, their apparent omnipresence, the interest of the general public and scholars periodically enhanced by spectacular discoveries, and finally by the increasing number of publications. However, although the first discoveries of votive offerings in Italy were made at an early date, virtually no votive contexts were published in a scientifically adequate manner until the 1960s (Cazanove forthcoming a). And it was not before 1986 that a series devoted to this topic was created, the Corpus delle Stipi votive in Italia, edited by Annamaria Comella and Mario Torelli.

Some Greek votive offerings were published earlier. When Carl Roebuck provided a catalogue of the votive terracottas from the Asklepieion of Corinth in 1951, he incidentally mentioned the existence of important comparative material in Italy, but added that information about them was scarce and that no monographs on the topic existed: “The votives from Corinth… were of terracotta… The only similar large finds of terracotta votives of this type are reported from the sanctuaries of Diana at Nemi and Veii, and from the Asklepieion on the Tiber island in Italy. Comparison with these, however, is difficult since they still await full publication” (Roebuck 1951, 112).

But it must be added that more than a century before the votives of Corinth, the first assemblage of anatomical ex-votos to be discovered and then immediately made known and illustrated in an almost exhaustive manner came from the excavations carried out by Henri Baudot from 1836 to 1842 at the sanctuary of the topical goddess Sequana near the Seine Springs in Burgundy. It was published in the Mémoires de la Commission des Antiquités du département de Côte d’Or as early as 1847 (Baudot 1842-1846). The plates [Fig. 1] that accurately illustrate the finds (architectural elements, inscriptions, offerings, but also instrumentum) can be easily compared with the artefacts preserved up to the present day. Body parts are associated, exactly as in the Central Italian deposits, with statues, heads and babies in swaddling clothes. The anatomical offerings at the Seine Springs are sculpted in limestone, but also embossed or punched on thin bronze plates: eyes, breasts, male and female genitalia, torsos and pelvises, and even schematic representations of internal organs (Deyts 1994). It wasn’t until more than a century later, in 1963, that hundreds of wooden offerings were discovered at the Seine Springs, making the sanctuary famous in scientific literature (Deyts 1983).

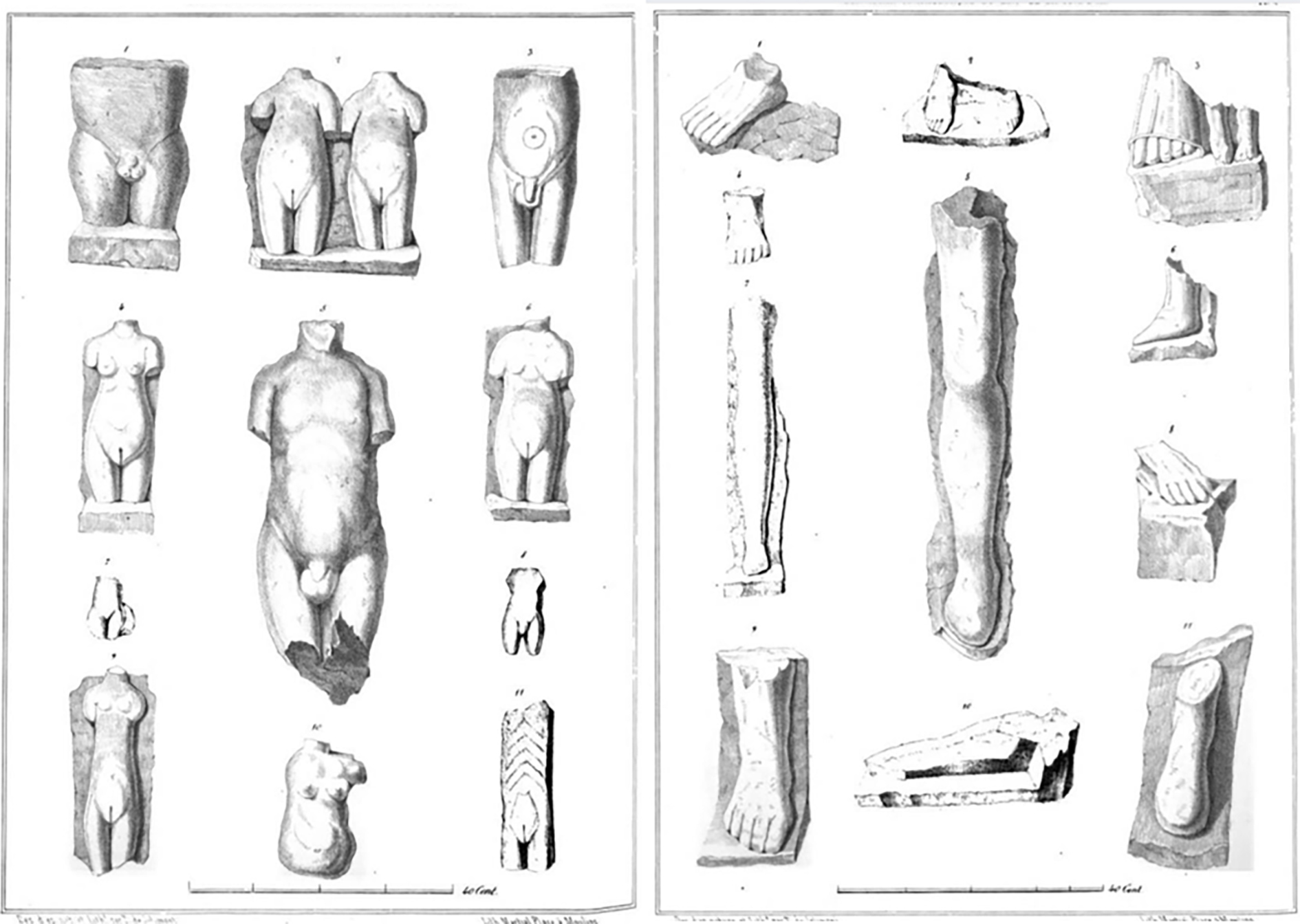

The year after the publication of the Seine Springs offerings, another local scholar, Prosper Mignard, released the finds from the temple of Apollo Vindonnus in Essarois, also in Burgundy (Mignard 1847-1852). The anatomical votives are very similar: limbs, male and female torsos and so on [Fig. 2]. It is also worth noting that, for the first time, offerings in limestone, wood and on bronze plates were found on the same cult site.

A third example of ancient excavations can be cited for our purpose, the Halatte forest temple in the Silvanectes territory (north of the Parisii) explored in 1873. The similarity of the votive facies with the offerings from the Seine Springs and Essarois – hundreds of sculptures in limestone – was immediately noted: heads, torsos, “a certain number of which… never had heads or legs, which proves that they were ex-votos relating to diseases of the organs of the trunk” (Caix de Saint-Aymour 1906), upper and lower limbs, breasts, complete statues, clothed or naked (the latter often with an oversized scrotum), children in swaddling clothes, statuettes and animal limbs. However, it was not until 2000 that this collection was fully published (Durand, Finon 2000).

Only one category of offerings will be examined here, representing not isolated limbs or organs, but the human trunk, either fully or partially represented. However, distinctions must be made. There are basically three different layouts of these truncated bodies, which exist in two formats: life-size and reduced, and were made of three materials: wood, stone and bronze (in thin bronze plate or in the round).

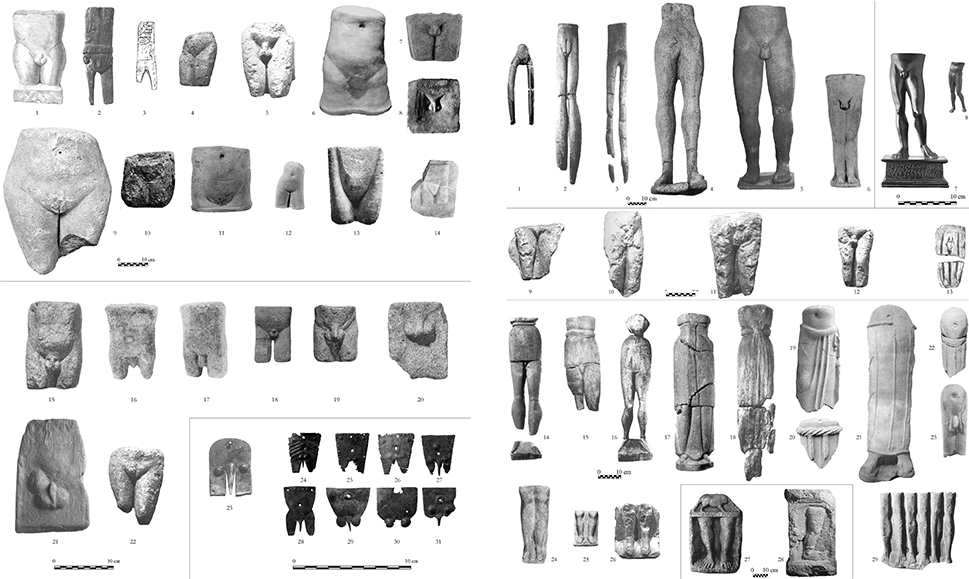

– the torso, without head or limbs (or with thighs only) [Fig. 4];

– the abdomen and thighs [Fig. 6];

– the lower part of the body, from the waist to the feet [Fig. 8].

The torsos

2 | Two plates from the publication by Mignard of the excavations at the sanctuary of Apollo Vindonnus (Essarois; Mignard 1847-1852).

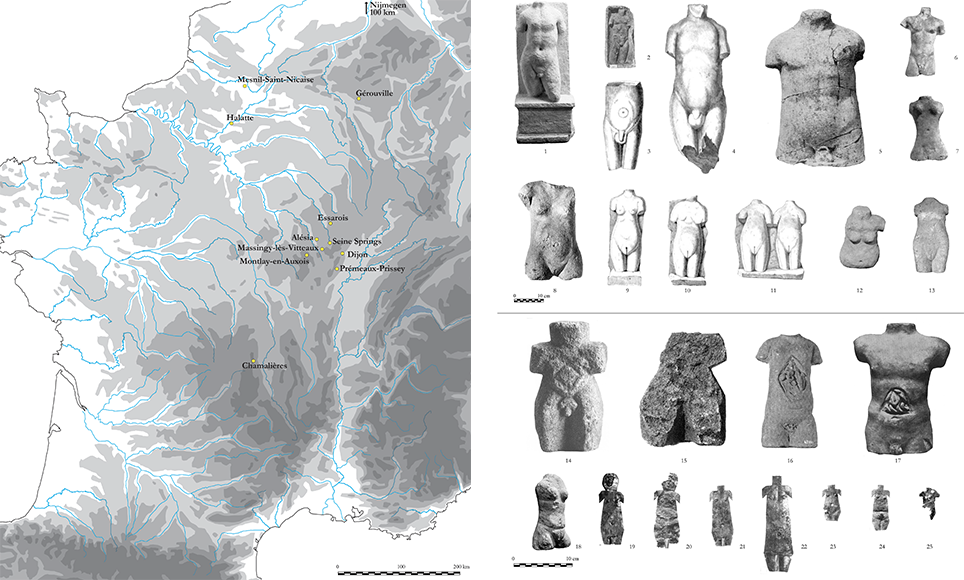

These are whole trunks, both male and female, from the neck to the groin and thighs. The three main sites where they have been found have already been mentioned: the sanctuary of Sequana at the Seine Springs, Essarois and Halatte [Fig. 3]. But there are others too, such as the cult place of Apollo Moritasgus at Alesia, from which a possible stone trunk bearing the dedication of a certain Diofanes was found (Espérandieu 1925, 7140; CIL 13, 11241), as well as a fragmentary pelvis from the 2023 excavations, and a small bronze plaque representing a torso whose sex cannot be determined due to its poor state of preservation [Fig. 4, 25].

The main characteristic of these artefacts is therefore that they are limbless and headless. The only exceptions are two schematic male figures from the Seine Springs with a small face embossed on the rounded cut-out above the body [Fig. 4, 19-20]. A third male bronze sheet in the shape of a trunk, also from the sanctuary of Sequana, has only the neck indicated [Fig. 4, 21], as do the 16 female examples [Fig. 4, 21-24]. In fact, all the other torsos from Gaul, whatever their origin or material, have no head, starting with those from the Seine Springs, in stone (10 examples in stone, mostly male [Fig. 4, 1-2], and wood, 11 examples, mostly female). The same is true of Central Italy [Fig. 4, 5-7] and Greece (where only three terracotta male torsos are known, from the Asklepieion in Corinth: Roebuck 1951, 121).

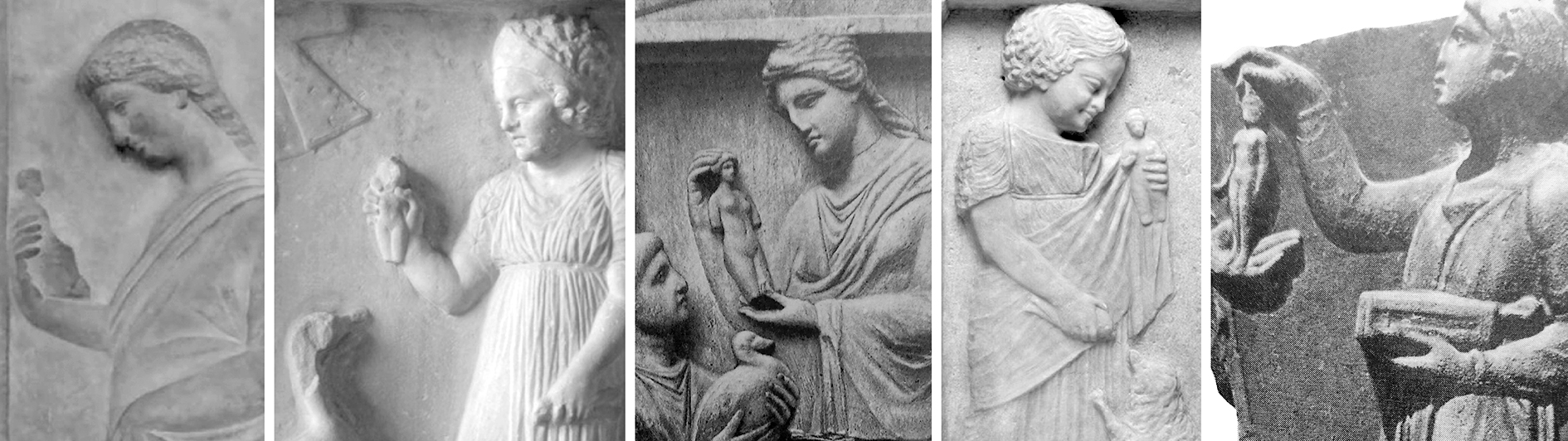

Because all these naked trunks from the Greco-Roman world are as much masculine as feminine, and above all because they are headless, it is impossible in my opinion to equate them, as J. Reilly did in an often-quoted paper (Reilly 1997), with the female statuettes held by girls on a series of Attic stelae [Fig. 5]. Some of these figures are complete, seated and clothed, while others are naked, without arms and with their legs cut off above the knee (Cavalier 1988). J. Reilly (following Daux 1973) rejects the idea that these figurines refer to the young girl’s offering, on the eve of her wedding, of the childhood toys she is about to leave behind. She is probably right to relate them to truncated terracotta figurines, which unfortunately have no definite provenance, making it impossible to determine their meaning (see also, on the female “poupées nues” from the Artemision of Thasos, Huysecom 2020). But she goes further: for her, “the so-called ‘dolls’ on ancient Athenian grave reliefs are not toys, but are votives” (Reilly 1997, 164); and again: “the truncated figures on the grave reliefs, I propose, are in actuality anatomical votives. The truncation of the figure, similar to the anatomical votives dedicated to healing gods, signifies its votive function” (Reilly 1997, 162). However, this truncation differs in at least one essential respect: while the head is present on the figurines in the stelae, it is always absent on the anatomical ex-votos, allowing the emphasis to be focused solely on the very core of the physical body. J. Reilly’s next step in interpretation is even more purely assertive: according to her, the truncated female figures on the funerary stelae “crafted as votives… reveal a complex of ideas about a female’s body and about an especially female concern, the achievement of menarche. The child is depicted with a dedication to ensure her healthy development and functioning as a woman” (Reilly 1997, 159). Unfortunately, there is no material evidence to support this reconstruction. There is very little archaeological evidence of whole votive torsos in the Greek world, only in Corinth, and only of men. And what about these male trunks? It would be methodologically wrong to ascribe a completely different meaning to them than to the female trunks. In any case, it would be prudent to completely separate the question of Greek female figurines without limbs but with heads, whose significance may continue to be debated, from that of ex-votos representing “real” trunks limbless and headless.

Despite these interpretative aporias, J. Reilly’s paper has been influential, even outside the Greek world, and even on the most informed studies of religious and social practices in Roman Gaul. A few years ago, it was suggested that the female torsos, pelvises, breasts and sexes at the Seine Springs were offerings made “on the occasion of rites celebrating the bodily maturity of girls and therefore the age of menarche” (Derks 2012, 71). T. Derks places the emphasis on rites of passage, adopting Van Gennep’s theses as the key to his anthropological interpretation. In spite of the importance one may wish to ascribe (or not) to the rites of passage in Roman society in general, and in votive practices in particular, it is difficult to follow the author if one challenges the Reilly’s paper on which he relies. There are other difficulties too: attributing the same overall meaning to a whole range of different offerings (female torsos, pelvises, breasts and vulvas) when there must have been a reason for these different focuses. The same applies to the truncated male representations at the Seine Springs and elsewhere: to assume that they were made solely to signify the generative capacity acquired at puberty seems limiting, especially for the full torsos where the focus is not particularly on sex. Finally, to take into account only votives showing sexual organs means isolating only a small part of the coherent assemblages formed by anatomical offerings, in Gaul and elsewhere, which include all parts of the body.

3 | Map showing where offerings in the shape of truncated bodies were found in Roman Gaul (O. de Cazanove).

4 | Truncated bodies: torsos. 1. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 72, 75, pl. 27, 1); 2. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 75, pl. 27, 2); 3. Essarois (Mignard 1847-1852, pl. 6, 3); 4. Essarois (Mignard 1847-1852, pl. 6, 5); 5. Lavinium, 13 are (Fenelli 1975, 255, D 12, fig. 349); 6. Veio (Bartoloni, Benedettini 2011, 567, H13 I 1, pl. 73 a-b); 7. Veio, Comunità (Bartoloni, Benedettini 2011, 569, H13 VI 1, pl. 75 a-b); 8. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 80, pl. 32, 3); 9. Essarois (Mignard 1847-1852, pl. 6, 4); 10. Essarois (Mignard 1847-1852, pl. 6, 6); 11. Essarois (Mignard 1847-1852, pl. 6, 2); 12. Essarois (Espérandieu 1911, 3431); 13. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 24, 00 5216); 14. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 73, pl. 26, 4); 15. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 74, pl. 26, 5); 16. Lanuvium, Tenuta Quarti (Haumesser 2017, 171, fig. 9.5); 17. Cales, Madrid, Museo Arquelogico Nacional, coll. Salamanca (Tabanelli 1964, fig. 12); 18. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 78, pl. 32, 1); 19-24. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 80-81, pl. 33, a-c, e, j, i); 25. Alesia, Moritasgus sanctuary (de Cazanove forthcoming b).

A different approach is therefore needed to interpret the truncated bodies, and first of all the whole torsos. At the Seine Springs, alongside examples of good craftsmanship [Fig. 4, 1-2, 8, 18], there is also a small, crude trunk, 22.5 cm high (Deyts 1994, 73-74), with the neck and the beginnings of the limbs indicated [Fig. 4, 14]. Above the male genitalia, a lozenge-shaped incision lies over the belly. Despite its schematic nature, this is undoubtedly a laparotomic opening designed to reveal the abdominal cavity. Of course, this in no way implies any surgical knowledge on the part of the craftsman or the commissioner, nor even less any trace of ‘temple medicine’, but more basically the simplified reproduction of earlier models. These models, showing the entrails in situ in the open trunk, already existed in Central Italy, particularly in Latium and Rome [Fig. 4, 16-17].

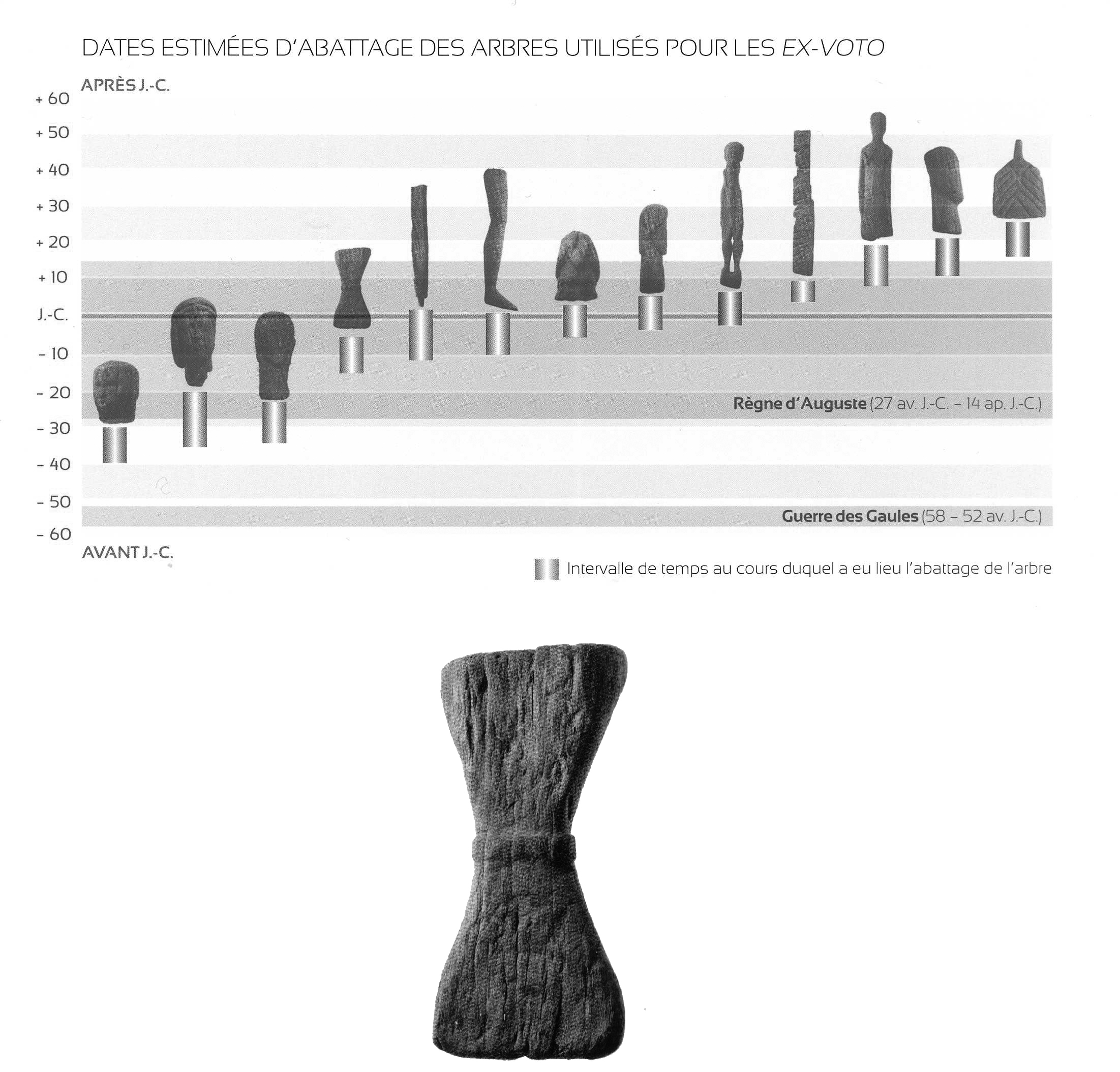

I won’t stress this point any further, as in a recent paper (Cazanove forthcoming a), I sketched out a typology of offerings representing open bodies in the votive deposits of Central Italy. It is more than enough to say that the small open trunk from the Seine Springs is one of several clear indications that representations of truncated bodies in Roman Gaul derive from Italian or, more broadly, Mediterranean antecedents. Chronology confirms this. A schematic wooden female trunk [Fig. 6] from the Seine Springs can be dated to shortly before the beginning of our era (i.e., one or two generations after the Gallic War) using dendrochronology (felling of the tree between 15th and 5th BC). Bronze and stone votive offerings are more recent, but are related to the same traditions, even if many links are missing to enable us to retrace this long history in detail.

In Italy, the open trunks showing the internal organs must refer, as we would expect, to illnesses affecting the interior of the body, or more generally to the dysfunction of the organism, supposedly restored (or avoided) by divine intervention. It is interesting to note that, in the same sanctuaries, there are both open and closed trunks, some of which belong to the same morphological types, e.g. in Tessennanno, Veio, Palestrina or Lavinium (Pantanacci). As a result, it is logical to assume that the meaning of closed trunks is, if not exactly the same, at least related to that of open torsos. We can therefore suppose that the closed trunks would also draw attention to what is embedded inside the body – but without showing it explicitly, unlike the complex representations of the entrails – and which enables it to function, but sometimes causes it to malfunction, leading to pain and illness. More visible ailments (wounds, injuries, and so on) should not be excluded from the occasions on which such artefacts were dedicated. These are polysemic votives to a certain extent, likely to refer, depending on the case, to anything that might affect the central part of the individual. In Gaul, as the existence of open trunks suggests, these offerings could also be interpreted in the same way.

5 | Young girls carrying figurines on funerary stelae. From left to right, Boston stela, Aristomache stela, Plangon stela, Calvet Museum stela, Melisto stela, fragment from Athens 1993 (after Cavalier 1988). Note the different types of figurines and poses, as well as the recurring presence of pets.

The abdomen and thighs

A second layout of truncated bodies shows only the lower half of the torso, or more precisely the combination of abdomen and thighs, from the navel to just above the knees [Fig. 7]. It exists in both male and female versions, always naked, in natural size or on a reduced scale, in wood, sheet bronze and limestone. It cannot be the equivalent (or at least the exact equivalent) of the trunks, because the body is cut differently[1]. Nor can it be a question of local peculiarities, of local ways of doing, since both can be found on the same sites.

6 | Dendrochronological dating of the wooden offerings from the sanctuary at the Seine Springs. Below, schematic female torso in oak dating from between 15 and 5 BC (Vernou 2011).

With regard to this particular layout of the truncated bodies, it is more credible to think that they are mainly representations of the male and female sexual organs, displayed in their bodily context. Firstly, because these representations of the abdomen and thighs focus on the genitalia, which are more or less at the centre of the artefact. Secondly, because there are no sexual organs on their own sculpted in stone in Roman Gaul; conversely, there are numerous male and female genitalia on a shield-shaped bronze plate (Seine Springs: Baudot 1842-1846, here [Fig. 1], and Deyts 1994, 76-78, pl. 28-31), but no female abdomens and thighs and relatively few male specimens [Fig. 1, 23-31]. There are several possible solutions: either the stone abdomens and thighs were an alternative to the bronze sheet genitalia for practical reasons (the metal ones were suspended; the stone ones had to stand upright) and/or for reasons of prestige (the stone offerings were larger and more expensive[2]). Either this means that different materials were preferred for the various parts of the body (in fact, not all types of anatomical votive are attested in metal sheets). Or lastly, it may be a question of chronology, depending on the date of appearance of anatomical votives in wood, metal or stone (Cazanove 2017, 63-69).

So the abdomens can in fact emphasise the sexual organs. But not only. They can also refer to any ailment, visible or invisible, external or internal, affecting this part of the body. Proof of this is provided by a small representation of an abdomen, in oak, from the Seine Springs (Deyts 1983, 88-89) [Fig. 7, 22]. It is atypical: below the male sex, clearly recognisable with the penis and testicles, there is no indication of the slit in the crotch (whereas the rounded belly is suggested in the upper part of the artefact). But there is more: above the right testicle, there is a ball-shaped protuberance whose shape and position leave no room for doubt: it is undoubtedly an inguinal hernia. This feature makes the object quite exceptional. Indeed, unlike the many attempts, made by doctors and surgeons who were also frequently collectors of antiquities (Haumesser 2017, 174-182), and who, often beyond all probability, sought to diagnose all manners of disease, lesions and deformities on the parts of the body they were examining, it has to be admitted that the identification of recognisable pathologies is almost always a doomed enterprise. There are very few exceptions, and this one is perhaps the clearest. It undoubtedly indicates a particular order from the commissioner, since in the vast majority of cases, the illness was not depicted on the ex votos. In any case, the oak abdomen from Alesia is not an offering linked to a passage of age or, despite the representation of the male genitalia, with sexuality either, but more banally with a pathology of the lower abdomen. It could be dangerous to extrapolate and give a univocal meaning to this iconographic type of ex voto in which the dedicator could put a range (albeit limited) of different interpretations.

These representations of the body cut between the navel and the inguinal region or the knees also had predecessors in Italy [Fig. 7, 6, 11, 12], at life-size or reduced (often on the same sites where are found complete open and/or closed trunks, for instance at Veio (Bartoloni Benedettini 2011, 567-571, pl. 73-76, H13) or Lavinium, Pantanacci (Attenni Ghini 2014), but also in Greece [Fig. 7, 7-8 and 13-14]. Sometimes the abdomen and thighs are detailed and developed, sometimes the emphasis is only on the pelvic region, but the groin and crotch areas are sketchily modelled. For our purposes, we should at least mention the dedication of Eleutherion (2nd-3rd century AD) in the Piraeus Asklepieion [Fig. 7, 8]. Eleutherion fulfils his vow “once cured” (therapeuteis) : Ἀγαθῇ Τύχῃ Ἐλευθερίων θεραπευθεὶς ἀνέθηκεν εὐχήν (Forsén 1991). It is clear that this type of ex-voto, which is often associated more with a request for fertility than a demand for healing, is in this case the image of a healed organ. More generally, the ex voto of Eleutherion clearly shows how artificial is the distinction between the “sanatio sphere” and the “fecundity sphere” (a binomial constantly found in studies on the composition and interpretation of votive deposits). The women’s pelvises found in the sanctuary of Aphrodite in Samos, with a dedication to the goddess by a certain Smaragdis [Fig. 7, 13], or in the Parian cult place of Eileithyia [Fig. 7, 14], the goddess of childbirth, easily suggest the reasons for such offerings, which could be varied: proper functioning or, on the contrary, affections of the sexual parts, sterility or its opposite, pregnancies, etc. Here, too, they are not to be contrasted with other parts of the body offered for the recovery of health. All the anatomical ex votos actually refer to the functioning or disfunctioning of the physical body, whatever the point or function affected.

The lower part of the body from the waist to the feet

7 | Truncated bodies: abdomens with thighs. 1. Essarois (Mignard 1847-1852, pl. 6, 1) ; 2. Seine Springs (Deyts 1983, pl. 23, 70); 3. Montlay-en-Auxois, Fontaine Segrain (Dupont, Bénard 1995, 70-72, fig. 10); 4. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 25, 00 5217); 5. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 37, 00 5099); 6. Veio (Bartoloni, Benedettini 2011, H13 VIII 1, pl. 76 a); 7. Athens, Asklepieion (Forsén 1996, 44, 1.28, fig. 25); 8. Piraeus, Asklepieion (Forsén 1996, 77-78, 10.2, fig. 77) ; 9. Halatte (Durand 2000, 138, fig. 64); 10. Alesia, Moritasgus sanctuary (Espérandieu 9, 7132); 11. Tarquinia, Ara della Regina (Comella 1982, D41, 110-111, pl. 74, c); 12. Collezione Palestrina, MNR (Pensabene 2001, 368, 332, pl. 94); 13. Samos, Aphrodite sanctuary (Forsén 1996, 93, 25.1, fig. 96); 14. Paros, Eileithyia sanctuary (Forsén 1996, 100, 31.7, fig. 106); 15. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, pl. 27, 4); 16-17. Massingy-lès-Vitteaux (Espérandieu 3, 2397); 18. Nijmegen (Espérandieu 9, 6630); 19. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, pl. 27, 7); 20. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, pl. 27, 8); 21. Seine Springs (Vernou 2011, 59, n. 60); 22. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 25, 00 5220); 23. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, pl. 30, 35); 24-31. Alesia, Moritasgus sanctuary (Cazanove forthcoming b).

8 | Truncated bodies: human lower parts. 1. Mesnil-Saint-Nicaise (Dietrich, Lecomte-Schmitt 2018, fig. 3); 2. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 492); 3. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 498); 4. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 499); 5. Cales (Ciaghi 1993, 185-187); 6. Tarquinia (Comella 1982, 113, D6I, pl. 76 a); 7-8. Gérouville (© Institut Archéologique du Luxembourg – Musée Archéologique d’Arlon); 9. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 28, 97 4003); 10. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 37, 00 5101); 11. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 36, 00 5096); 12. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 35, 00 5092); 13. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 43, 00 5194); 14. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 465); 15. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 463); 16. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 474); 17. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 484); 18. Chamalières (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 488); 19. Veio, Comunità (Bartoloni, Benedettini 2011, 580, H16 I 1, pl. 79 a); 20. Veio, Comunità (Bartoloni, Benedettini 2011, 582, H16 V 1, pl. 80 a); 21. Veio, Comunità (Bartoloni, Benedettini 2011, 581, H16 IV 1, pl. 79 d); 22. Tessennano (MacIntosh Turfa 2004, 365, 317, pl. 96); 23. Tessennano (Costantini 1995, 82, pl. 33, E5 I1, p. 33 b); 24. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 101, pl. 43, 5); 25. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 101, pl. 43, 3); 26. Halatte (Durand, Finon 2000, 76, 00 5249); 27. Prémeaux-Prissey (Espérandieu 13, 8228); 28. Dijon (Deyts 1998, 56); 29. Seine Springs (Deyts 1994, 101, pl. 43, 1).

The third way of truncating the human shape is to keep only the lower part of the body, starting above the navel and extending down to the two feet. It is well documented in Roman Gaul, with 41 wooden specimens at Chamalières (Source des Roches) (Romeuf, Dumontet 2000, 75-77, 463-503) [Fig. 8, 2-4 and 14-18], plus a more recent specimen from preventive archaeological excavations at Mesnil-Saint-Nicaise (Dietrich, Lecomte-Schmitt 2018) [Fig. 8, 1]. There are also stone sculptures at Halatte [Fig. 8, 9-13 and 26], in the sanctuary of Sequana (Seine Springs [Fig. 8, 24-25 and 29]) and elsewhere in Burgundy [Fig. 8, 27-28]. We should also mention two bronze statuettes from a cult place at Gérouville [Fig. 8, 7-8], not far from the border between France and Belgian Luxembourg (Namur 1848). In the current state of research, we know of no lower parts of the body made of bronze sheet.

This specific impagination of truncated bodies is itself found in three forms : in the first one [Fig. 8, 1-4 and 7-13], the lower part of the human figure is entirely naked, from the navel to the feet, and can be male, female or neutral, i.e., without a recognisable sex. The upper part of the object ends in different ways: the top can be flat or domed, like the abdomens previously examined. The feet (when preserved) are bare.

In the second version (only represented in Gaul at Chamalières [Fig. 8, 14-18], the lower part of the body is dressed with a short tunic for men and a long garment for women, cinched at the waist by a belt. Above, the artefact ends in the shape of a tablet which may be strongly protruding or a vaguely globular mass.

Finally, in a third version [Fig. 8, 24-29], the representation starts a little lower, between the groin and the knee, and ends, as before, at the feet. The two legs are shown together, but no part of the abdomen is visible. They are therefore no longer truncated bodies in the sense that we previously used the term, but their iconographic proximity to human lower parts justifies their inclusion here. They are found in stone at Halatte and Seine Springs, as well as at neighbouring sites (Prémeaux). One unicum (in Dijon [Fig. 8, 28] is represented by an ex voto with the legs in profile and the feet shod (the curved ends of the two shoes are visible, one behind the other) accompanied by a dedication to the god Britos (Deyts 1998, 56, 23; AÉ 1926, 59).

This very specific truncation, which leaves only the lower part of the body visible, has clear predecessors in Italy. The 9 terracotta votives from the Latin colony of Cales (the specimen reproduced here is life-size [Fig. 8, 5] can easily be compared with the best nude exemplars from Chamalières (also life-size [Fig. 8, 4]) or, on a smaller scale, with the half-statuettes from Gérouville [Fig. 8, 7-8]. In a previous study, I have already assumed a derivation from Italy to Gaul (Cazanove 2017, 72-74), but it is difficult to be more precise due to the lack of intermediate links.

The derivation seems even more obvious for the second version, i.e., the clothed lower parts of the body, at least the female ones. This form of anatomical gift is atypical and even paradoxical because the very nature of an offering representing a part of the body is to represent it naked, in its physical materiality and not as a social person, distinguished by clothing. The fact that the same exception to the rule existed in Italy and Gaul, for the same type of particular layout, suggests that they should be interpreted in the same way. The same iconographic attributes can also be seen, in particular the belt tied at the waist [Fig. 8, 18-20]. A detailed discussion of the various hypotheses that could be put forward in this respect would take us too far. We will simply note that in Central Italy the clothed lower part of the body appears to be the feminine counterpart of the naked male lower part. The case of Tessennano is clear on this respect [Fig. 8, 22-23]. A selective pudor is displayed (genitalia apparent / not apparent). Similarly, the series of clothed lower bodies from Veio (9 examples + 4 fragments) refers more to a feminine iconography (Bartoloni Benedettini, 499). At Chamalières, things are more complex, with both male and female clothed half-bodies, while at Halatte there are male (mostly) but also female nude lower bodies. The image of pudor shifts, but remains in display, however paradoxical this may seem for anatomical ex votos, which should show naked body, limbs and organs. However, the basic principle of the anatomical ex voto is preserved, i.e., to show only the part of the body directly concerned by the vow. Just as the torsos, as we saw earlier, refer to the functioning of the body beyond the skin, so the clothed human lower parts could refer, beyond the garment, to the legs, the genitalia and the inguinal area (we can leave the range of possibilities open) even if the the naked body is not shown, except for its extremities: the feet and the navel.

The third variant is an abbreviated adaptation of the first, with the two legs shown together, but without the abdomen. There are no archaeologically attested Italian parallels, but we can assume that the “legs from the feet to the groin” (femina ap pedibus ad inguen, femina here meaning femora) attested epigraphically in the dedication of L. Marcius Grabillo at the Bagno Grande of San Casciano dei Bagni (Gregori 2023, 195-198) refers to something similar. In the inscription, the alternation between the plural (pedibus) and singular (inguen) must be significant and refer to pairs of legs, connected at the groin. The femina=femora offered by Marcius Grabillo were somewhat intermediate between our variant 1 (with abdomen up to the navel) and our variant 3 (cut below the connection with the groin). Did Grabillo offer six independent legs, three pairs of legs, or even a single ex-voto representing all six? It is not impossible. At the Seine Springs, there is a limestone slab on which three pairs of legs are sculpted in very high relief, six in all, half their natural size [Fig. 8, 29]. This is, of course, only comparative material, but it suggests that all possibilities should be left open.

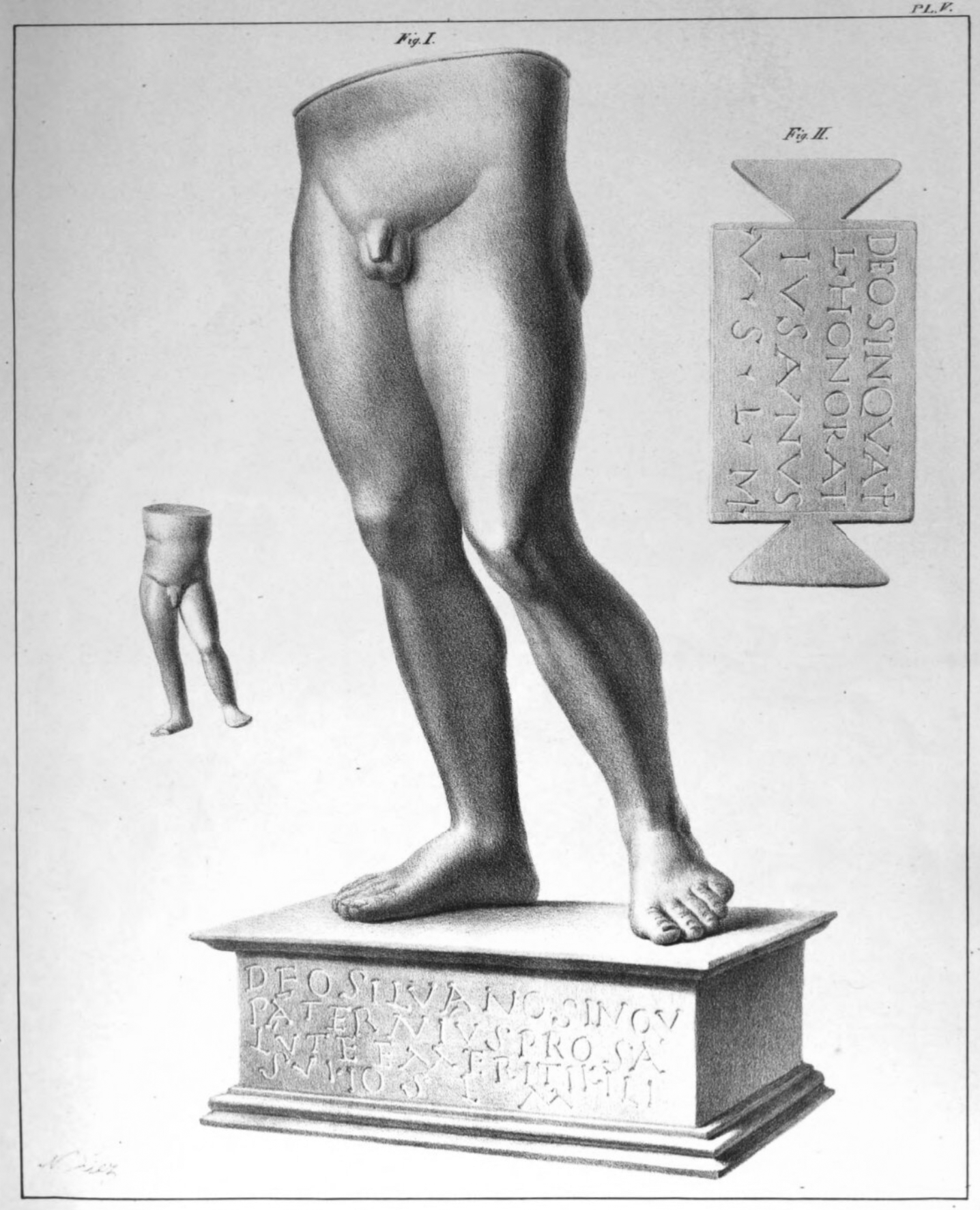

The two statuettes discovered at Gérouville (Namur 1848), depicting a naked male lower body, are the antithesis of the schematic ex-votos previously examined [Fig. 9]. With their pronounced contrapposto, they are direct echoes of the great plastic, probably taken from moulds intended for statuettes of divinities. One of them is mounted on a base bearing a dedication to the god Silvanus Sinquatis (CIL 13, 3968). The vow pro salute made by Paternius for his son Emeritus, could possibly have had, in another context, the more general meaning of a vow for the overall safeguard of the individual, for the good state of his affairs. But here, as it applies to a partial reproduction of the human body, it cannot be seen as referring to any other thing than good physical health.

Conclusive remarks

9 | The two bronze statuettes representing truncated lower bodies, from Gérouville (Géromont) (Namur 1848, pl. 5).

As we saw above, there is a large amount of ancient data available on anatomical ex voto and related offerings (children in swaddling clothes, heads, statues) in Roman Gaul, some of them published very early on; our knowledge is also growing exponentially today, thanks to preventive and programmed excavations. All these results should be put to greater use in current debates on the significance and wide distribution of this category of offerings (from the Aegean basin and Anatolia to Italy, Spain and Gaul), even if chronocultural specialisations remain a source of partitioning. This is not to deny the existence of areal specificities, nor to avoid a careful study of all the variances. Nevertheless, the morphological similarities encountered in each category of anatomical ex votos in the different areas where they are present (e.g. the three ‘layouts’ of the truncated body: torso, abdomen with thighs, lower body from the feet to the groin - but the same could be said for practically all classes of anatomical votive) strongly suggest derivations and borrowings (which does not, of course, rule out re-elaborations, re-semanticisations or autonomous developments). In short, these artefacts must be considered from a Mediterranean and long-term perspective (Hughes 2017, albeit from a different angle), against the ever-recurrent temptation of localism.

The chrono-cultural and socio-cultural contextualisation of anatomical offerings, which in Italy remains contentious around the never-ending Romanisation issue (Papini 2024, 831), becomes largely depassionate in Gaul, where no one will deny that this class of offerings appeared after the Caesarian conquest. This is undoubtedly confirmed not only by the Latin dedications that commonly appear on these objects, but also by the very precise dendrochronological dating of the first wooden votives, some less than half a century after the Gallic War (but always afterwards) [Fig. 6]. These wooden ex votos remained common until the end of antiquity, and beyond. However, when studying the sanctuaries of Gaul, it is important to avoid schematic oppositions between ‘before’ and ‘after’ the provincialisation of these territories. Here too, the process of evolution and transformation of sanctuaries is a long-term one.

Another question still under debate is the meaning to be assigned to anatomical ex votos, i.e., the occasion of the offering. Reacting against the long-dominant medical gaze of anatomical offerings, another line of studies denied that these objects - or at least some of them - had anything to do with physical health: legs and feet would be offerings made, not for a cure, but on return from a journey, etc. Where the medical gaze placed all anatomical votives on the same level, believing to discover signs of illness everywhere (unsuccessful attempts with very rare exceptions, as seen above), a non-medical reading tends to unravel the unity of this category, disregarding the strong typological and contextual similarities that these objects have in common (Cazanove 2013, 23-24).

In Gaul at least, where wooden anatomical ex-votos are well attested right up to the transition between Late Antiquity and the High Middle Ages (and beyond), there can be no doubt about it. They unquestionably concerned physical health. As a young man, Saint Gal, the future bishop of Clermont (489-551), set fire to a temple in Cologne where “limbs were carved in wood according to the pain that affected each of them”[3]. The Synod of Auxerre (561-605) forbids the fulfilling of vows “among the thickets, nor near sacred trees or springs; if someone has subscribed a vow, let him spend a vigil in church and fulfill this vow for the benefit of the poor; and let him in no way presume to do so with objects carved in wood: neither a foot, nor a man”. Pirmin of Reichenau (670-753), in the Scarapsus, certainly reproducing an earlier prohibition, admonishes: “do not make or place wooden limbs at crossroads, on trees or elsewhere, because they cannot give you any healing” (Hauswald 2006, 19-21, 85-86). This is enough to invalidate the recurrent theory that votive feet or legs are gifts made after a journey, in some way comparable to pro itu and reditu footprints. More generally, the membra mentioned by Gregory of Tours in the Life of Saint Gall must refer to the different categories of anatomical ex-voto, since each one targets the variety of painful diseases that affect them.

The truncated bodies could not have had a different meaning. As we have seen, Paternius’ vow pro salute Emeriti filii must, according to the context, concern the physical salus of his son. More generally, the truncated male and female bodies, in their three main variations that we have briefly reviewed, refer to the functioning or dysfunction of the body, whether apparent or hidden. In Italy, the closed or open trunks (the latter revealing the entrails) are partly of the same formal types and are found on the same cult sites. Although not identical, their meanings are probably related. In Gaul, only one open torso is known (two others are hypothetical), but we can assume that the conceptual framework for interpreting the other trunks is similar: the diseases inside the body and the health restored within it. The fact that these bodies are headless and limbless draws attention specifically to that part of the individual, even if most of it remains invisible. It is also the absence of a head that prevents the votive torsos from being likened to the statuettes held by little girls on Greek funerary stelae. The other two variations of truncated bodies (abdomens with thighs, lower parts of the body from the feet to the navel) draw more attention to the lower abdomen, the inguinal region, the apparent sexual organs, and of course the legs. The occasions for vows could be differentiated, and I think we should retain the idea of a “limited polysemy” of these offerings, within a range of meanings that were acceptable and recognised by the entire group of worshippers.

Notes

[1] It is sometimes difficult to attribute some fragmentary anatomical pieces to one of the three arrangements of the truncated body distinguished here. If the body is accidentally broken at the waist or knees, it cannot be ruled out that it continued upwards (in which case it would be a torso) or downwards (in which case it would be a lower part of the body).

[2] Even if one must remain cautious when faced with the financial argument, too often put forward to justify the choice of materials that are in reality inexpensive (terracotta, limestone, bronze plates...). The real leap forward, both economically and qualitatively, is that of lost-wax metalworking, as demonstrated today by the extraordinary finds at San Casciano dei Bagni (Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023). There is no equivalent in Roman Gaul, but the existence of relatively expensive anatomical offerings (i.e., in metal in the round) is indicated by the bronze statuettes from Gérouville (figs. 8, 7-8 and 9).

[3] Grégoire de Tours, Vitae Patrum, VI, 2: erat autem ibi fanum quoddam diuersis ornamentis refertum, in quo barbaries proxima libamina exhibens usque ad uomitum cibo potuque replebatur, ibique et simulacra ut deum adorans, membra secundum quod unumquemque dolor attigisset, sculpebat in ligno.

Bibliography

- Bartoloni, Benedettini 2011

G. Bartoloni, M.G. Benedettini, Veio, Il deposito votivo di Comunità (Scavi 1889-2005), Corpus delle stipi votive in Italia, XXI, Roma 2011. - Baudot 1842-1846

H. Baudot, Rapport sur les découvertes faites aux sources de la Seine, “Mémoires de la Commission des Antiquités de la Côte-d’Or” 2 (1842-1846), 95-144. - Caix de Saint-Aymour 1906

V.A. Caix de Saint-Aymour, Le temple de la forêt d’Halatte et ses ex-voto, in LXIIe Congrès archéologique de France (Beauvais 1895), Paris 1906, 344-361. - Cavalier 1988

O. Cavalier, Une stèle attique classique au musée Calvet d’Avignon, “La revue du Louvre et des musées de France” 4 (1988) 285-293. - Cazanove 2013

O. de Cazanove, Ex voto anatomici animali in Italia e in Gallia, in F. Fontana (a cura di), Sacrum facere. Atti del I Seminario di Archeologia del Sacro (Trieste, 17-18 febbraio 2012), Trieste 2013, 23-39. - Cazanove 2017

O. de Cazanove, Anatomical votives (and swaddled babies): from Republican Italy to Roman Gaul, in J. Draycott, E.J. Graham (eds.), Bodies of evidence. Ancient anatomical votive, past, present and future, London-New-York 2017, 63-76. - Cazanove, forthcoming a

O. de Cazanove, Assemblaggi con offerte anatomiche: la necessità di tipologie d’insieme. Il caso dei votivi cd. poliviscerali, in M. Bellelli, C. Rizzo, M. Arizza (a cura di), Cerveteri, Roma e Tarquinia. Un seminario di studi in ricordo di Mauro Cristofani e Mario Torelli, forthcoming. - Cazanove forthcoming b

O. de Cazanove (éd.), Le lieu de culte d’Apollon Moritasgus à Alésia, forthcoming. - Ciaghi 1993

S. Ciaghi, Le Terrecotte figurate da Cales del Museo Nazionale di Napoli. Sacro Stile Committenza (Studia Archaeologica, 64), Roma 1993. - Comella 1982

A. Comella, Il deposito votivo presso l’Ara della Regina (Materiali del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Tarquinia, 4), Roma 1982. - Costantini 1995

S. Costantini, Il deposito votivo del santuario campestre di Tessennano (Corpus delle stipi votive in Italia, VIII), Roma 1995. - Daux 1973

G. Daux, Les ambiguïtés de grec KOPH, “Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres” 117, 3 (1973), 382-393. - Derks 2012

T. Derks, Les rites de passage dans l'empire romain: esquisse d'une approche anthropologique, in P. Payen, E. Scheid-Tissinier (éds.), Anthropologie de l'antiquité. Anciens objets, nouvelles approches, Turnhout 2012, 43-80. - Deyts 1983

S. Deyts, Les bois sculptés des sources de la Seine, Paris 1983. - Deyts 1994

S. Deyts, Un peuple de pélerins. Offrandes de pierre et de bronze des Sources de la Seine, Dijon 1994. - Deyts 1998

S. Deyts (éd.), À la rencontre des dieux gaulois. Un défi à César, Dijon 1998. - Dietrich, Lecomte-Schmitt 2018

A. Dietrich, B. Lecomte-Schmitt, Ex-voto anatomiques en bois de l’antiquité. Magny-Cours (Nièvre) et Nesle Mesnil-Saint-Nicaise (Somme), in G. Fercoq du Leslay, K. Fechner, E. Gillet (éds.), Sacrée science! Apports des études environnementales à la connaissance des sanctuaires celtes et romains du nord-ouest européen, Amiens 2018, 229-236. - Dupont, Bénard 1995

J. Dupont, J. Bénard, Le sanctuaire gallo-romain à bois votifs de la Fontaine Segrain à Montlay-en-Auxois (Côte-d’Or), “Revue archéologique de l’Est” 46 (1995), 59-78. - Durand 2000

M. Durand (éd.), Le temple gallo-romain de la forêt d’Halatte (Oise), Amiens 2000. - Durand, Finon 2000

M. Durand, C. Finon, Catalogue des ex-voto anatomiques du temple gallo-romain de la forêt d’Halatte (Oise), in M. Durand (éd.), Le temple gallo-romain de la forêt d’Halatte (Oise), Amiens 2000, 11-91. - Espérandieu 1910

É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine 3, Paris 1910. - Espérandieu 1911

É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine 4, Paris 1911. - Espérandieu 1925

É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine 9, Paris 1925. - Espérandieu 1949

É. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine 13, Paris 1949. - Fenelli 1975

M. Fenelli, Votivi anatomici, in F. Castagnoli et al., Lavinium II. Le tredici are, Roma 1975, 253-303. - Forsén 1991

B. Forsén, Gliederweihungen aus Piraeus, “ZPE” 87 (1991), 173-175. - Forsén 1996

B. Forsén, Griechische Gliederweihungen. Eine Untersuchung zu ihrer Typologie und ihrer religions- und sozialgeschichtlichen Bedeutung, Helsinki 1996. - Gregori 2023

G.L. Gregori, Iscrizioni latine su votivi in bronzo: divinità, devote, formulari, in E. Mariotti, A. Salvi, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Il santuario ritrovato 2. Dentro la vasca sacra. Rapporto preliminare di scavo al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2023, 195-203. - Haumesser 2017

L. Haumesser, The open man: anatomical votive busts between the history of medicine and archaeology, in J. Draycott, E.J. Graham (eds.), Bodies of evidence. Ancient anatomical votive, past, present and future, London-New-York 2017, 165-192. - Hauswald 2006

E. Hauswald, Pirmins Scarapsus. Einleitung und Edition, Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS), 2006 - Hugues 2017

J. Hugues, Votive Body Parts in Greek and Roman Religion, Cambridge 2017. - Huysecom 2020

S. Huysecom, Les «poupées nues» féminines en terre cuite de l’Artémision de Thasos: Typologie, Interprétation, Utilisation, in S. Donnat, R. Hunziker-Rodewalt, I. Weygand (éds.), Figurines féminines nues, de l’Egypte à l’Asie Centrale, Paris 2020, 329-345. - MacIntosh Turfa 2004

J. MacIntosh Turfa, Weihgeschenke: Altitalien und Imperium Romanum. B. Anatomical votives, in Thesaurus cultus et rituum antiquorum (ThesCRA), 1. Processions, sacrifices, libations, fumigations, dedications, Los Angeles 2004, 359-368. - Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023

E. Mariotti, A. Salvi, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Il santuario ritrovato 2. Dentro la vasca sacra. Rapporto preliminare di scavo al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2023. - Mignard 1847-1852

P. Mignard, Historique d'un temple dédié à Apollon près d’Essarois, Côte-d'Or, “Mémoires de la Commission des Antiquités de la Côte-d’Or” 3 (1847-1852), 111-161. - Namur 1848

A. Namur, Rapport sur les inscriptions votives et statuettes trouvées à Géromont près des Gérouville (Luxembourg belge), et sur les tombes gallo-franques de Wecker découvertes en 1848 s.l, s.n. - Papini 2024

M. Papini, Bodies in pieces in Central Italy: votives, in M. Maiuro, J. Botsford Johnson (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Pre-Roman Italy (1000-49 BCE), Oxford 2024, 822-837. - Pensabene 2001

P. Pensabene, Le terrecotte del Museo nazionale romano. II. Materiali dai depositi votivi di Palestrina, collezioni “Kircheriana” e Palestrina, Roma 2001. - Reilly 1997

J. Reilly, Naked and limbless. Learning about the feminine body in ancient Athens, in A.O. Koloski-Ostrow, C. Lyons (eds.), Naked Truths: women, sexuality, and gender in classical art and archaeology, London-New-York 1997, 154-173. - Roebuck 1951

G. Roebuck, Corinth XIV. The Asklepieion and Lerna, Princeton 1951. - Romeuf, Dumontet 2000

A.-M. Romeuf, L. Dumontet, Les ex-voto gallo-romains de Chamalières (Puy-de-Dôme). Bois sculptés de la source des Roches, Paris 2000. - Tabanelli 1962

M. Tabanelli, Gli ex voto poliviscerali etruschi e romani, Firenze 1962. - Vernou 2011

C. Vernou (éd.), Ex-voto. Retour aux sources. Les bois des sources de la Seine, Dijon 2011.

There is a large amount of ancient data available on anatomical ex voto in Roman Gaul, some of them published very early on (Seine Springs, Essarois, Halatte). Only one category of these offerings is examined here, representing the human trunk, either fully or partially represented. There are three different layouts of these truncated bodies, which exist in wood, stone and bronze : the torso, without head or limbs (or with thighs only) ; the abdomen and thighs ; the lower part of the body, from the waist to the feet. These three layouts of truncated bodies have clear antecedents in Greece and Italy, so they should be considered from a Mediterranean rather than a narrowly local perspective. They undoubtedly appeared after the Roman conquest (dendrochronological dating, language of dedications) and concern the preservation or restoration of the body's good condition, focusing specifically on the part affected. Occasions for vows could be differentiated, and offerings could present a certain degree of polysemy, but a "limited polysemy", within a range of meanings acceptable and recognized by the entire group of worshippers.

keywords | ex voto; Anatomical offerings; Roman religion and cults; Roman Gaul.

questo numero di Engramma è a invito: la revisione dei saggi è stata affidata al comitato editoriale e all'international advisory board della rivista

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: O. de Cazanove, Offering truncated bodies in Roman Gaul. Layouts, antecedents and interpretations, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 214, luglio 2024, 127-148 | PDF