From DEM to reconstruction of the ancient thermal landscape.

Worship spaces and public areas in the context of the Bagno Grande in San Casciano dei Bagni

Emanuele Mariotti

Abstract

1 | Aerial view of Bagno Grande area from south-west, San Casciano dei Bagni (photo by E. Mariotti). Black circle: Bagno Grande spring and baths.

This paper aims to offer a preliminary reading of the archaeological topography of the Bagno Grande, analyzing the morphology of the terrain in combination with the results of geophysical prospecting, around the main spring of the Cassianense thermal system: the Bagno Grande area [Fig. 1].

The area of Bagno Grande, located at an average altitude of 510-512 m a.s.l., is characterized by a jagged, irregular soil conformation, with numerous jumps in elevation due as much to the original orography of the area as to the numerous anthropic interventions, linked both to the exploitation of the thermal waters and to the intensive agro-pastoral use that lasted for centuries without interruption. The hill of “Monte Santo” dominates the beginning of the Valley of the Elvella, the stream that flows at the foot of the present village of San Casciano dei Bagni, collecting along its course all the thermal manifestations of the territory (except for a spring located north of the Borgo) (Tabolli, Mariotti 2021, 109). Just from “Monte Santo”, where clays and travertines meet, the terrain descends irregularly south and southeast, forming a series of apparent terraces that set the Bagno Grande spring and its twin about 30 m further south (Tabolli, Mariotti 2021, 110-11), until it descends to the “gora”, a basin a little further downstream that served the old mill and remains of uncertain age. Toward the west, on the other hand, the present elevation of the suface is higher than the springing of the waters, forming a plateau that “encloses” the buildings of the Bagno Grande, ancient and modern (Fortini et alii 2023) in this direction, and then also descends more regularly toward the south and east. In this complex orography, marked and punctuated also by what remains of wine-growing crops, abandoned olive groves and reed beds, fit the surface archaeological outcrops: remains of structures still visible as fragments of walls, elements of ancient canalizations (not in their original position), dispersions of materials (Pocobelli 2021), as well as the structures that emerged from the excavation (Mariotti 2021; Mariotti 2023).

Such notes on the “exterior” appearance of the “landscape” around the Great Bath complex are not superfluous, but constitute the first step toward a reading of the terrain, in this case “not superficial”. All the vegetal, historical, anthropical and morphological elements, and related to the natural orography of the context, determine and have determined the current appearance of the place, as well as the surface on which the archaeologist walks and carries out his investigations. The “shape of the land”, far from being just a topographical representation, or a more or less accurate contour map in which to place archaeological evidence, itself becomes an archaeological source, even when this shape does not present striking elements of clarity. In the case of the Bagno Grande, it is the complex result of natural and anthropogenic factors, according to a basic typology already discussed for other contexts (Mariotti 2010; Mariotti 2012). One must assume an original conformation descending from the Monte Santo hill towards to the south, most likely more regular than it is today, and in line with the flow of spring waters along the fault line already mentioned (Tabolli, Mariotti 2021). Ancient anthropic activities (Etruscan and Roman periods for what excavation and research data currently tell us) would then take place on this base, certainly adapting to the soil surface and, at the same time, modifying it for the realization of those more or less complex structures aimed at the use of thermal waters (Mariotti, Tabolli 2021; Mariotti, Salvi, Tabolli 2023; Osanna, Tabolli 2023; Osanna, Tabolli 2024). The ancient period was followed by further activities in the medieval, Renaissance and post-Renaissance periods, although the archaeological traces are so far faint (Chellini 2002, 13-14; Mariotti et alii 2024). They further modified the morphology of the terrain, overlapping the ancient structures and creating further unevenness, carryovers of materials [Fig. 02], most likely raising the water-level of the previous period. The agropastoral activities of the last two centuries, when the thermal acmé of San Casciano dei Bagni had waned (Morelli 2021; Fortini et alii 2023; Tabolli 2023) did nothing more than obliterate and regularize an archaeological surface that had largely interacted with the geological substratum. The snapshot obtained by using a DEM (Digital Elevation Model or DTM, Digital Terrain Model), as with any geophysical or remote sensing survey in general (Boschi 2020), is that of a synchronic image of a diachronic process, of which we see “only” the surface with its ultimate form, determined by the superposition of phases and periods, and something below it, with all the cautions and verifications that are necessary with respect to possible interpretations. Nevertheless, an attempt at an integrated reading between the DEM, geophysical prospections, and the planimetry of visible structures is all the more necessary (Forte, Williams 2003; Summers 2003; Summers 2008; Mariotti 2008; Mariotti 2010; Materazzi et alii 2024), when such a perspective is completely or nearly lacking in ancient thermal contexts, as areas dedicated to sacred and healing thermo-mineral waters (for a comprehensive summary Chellini 2002; Giontella 2006; Giontella 2012; Bassani et alii 2019).

2 | Aerial view from east of the overlapping of ancient and modern structures of Bagno Grande (yellow area, photo by E. Mariotti).

Even in this type of reading, the topographical and archaeological focal point remains the Bagno Grande spring with its two springs, main and secondary. On them and on the use of their waters, depends the whole context set up with buildings, appropriate spaces and canalizations in Roman times and before that in Etruscan times, albeit with traces that are still barely visible (Mariotti et alii 2024).

Geophysics

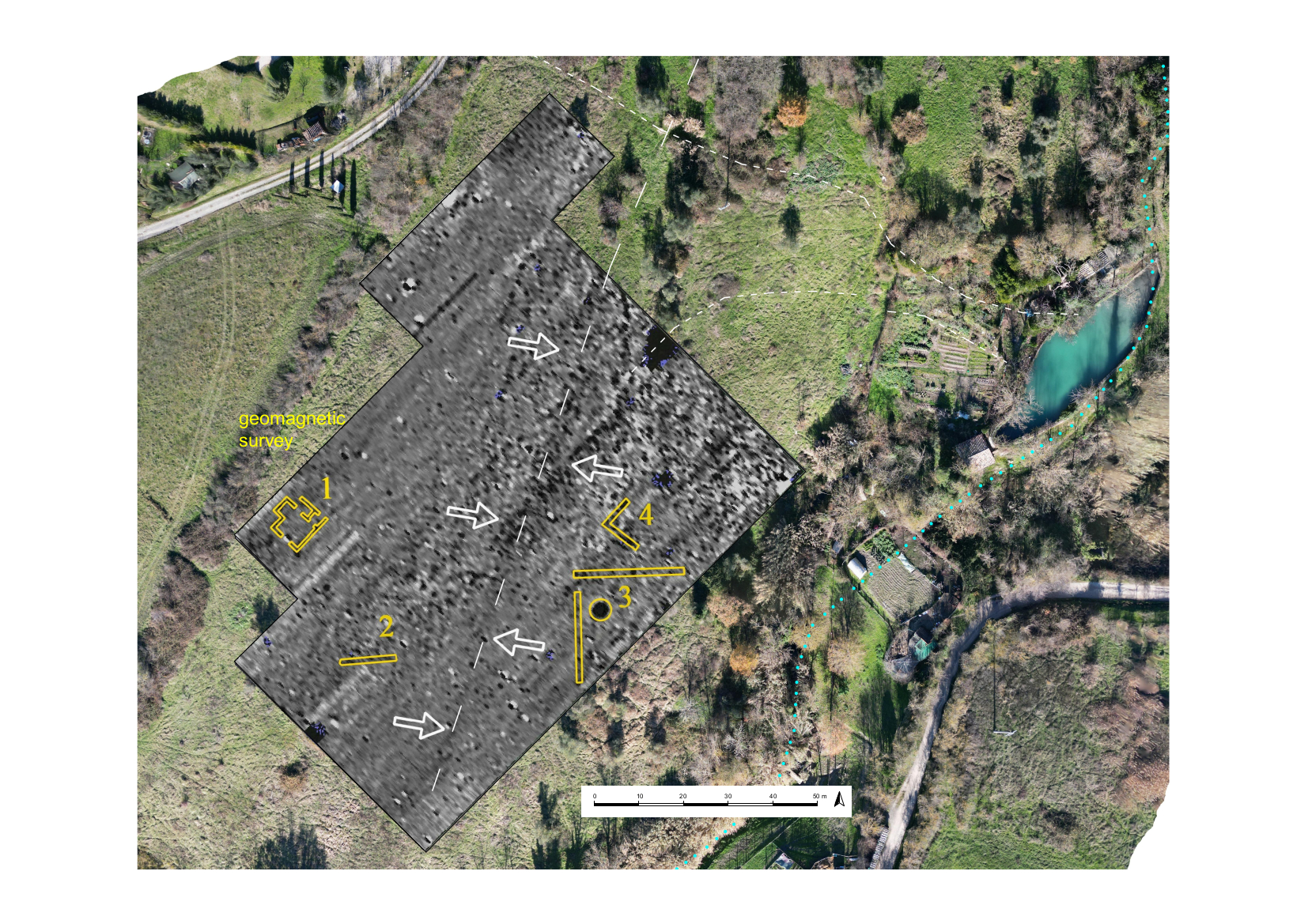

3 | Bagno Grande, southern-west area: geomagnetic survey (Felici, Morelli 2021, graphic processing and aerial photo by E. Mariotti).

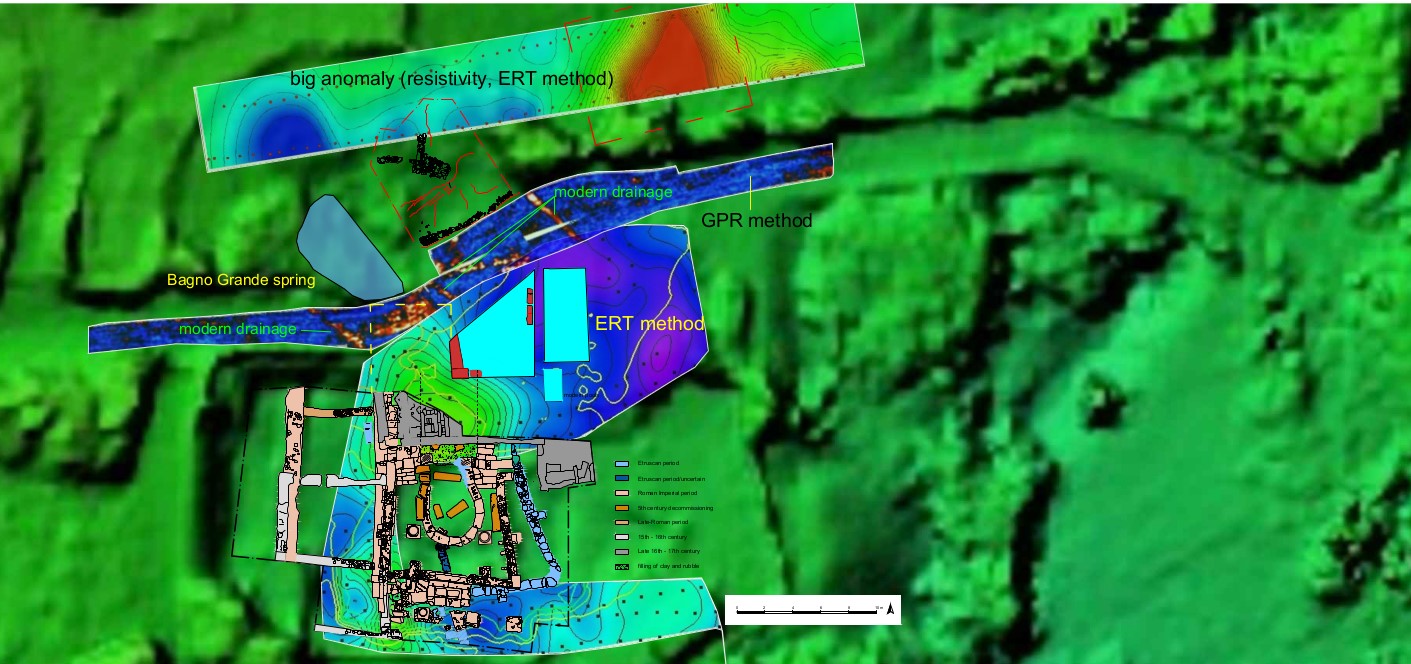

4 | Bagno Grande: different geophysics survey and strong anomalies in the archaeological/baths area (Felici, Morelli 2021, graphic processing and interpretation by E. Mariotti).

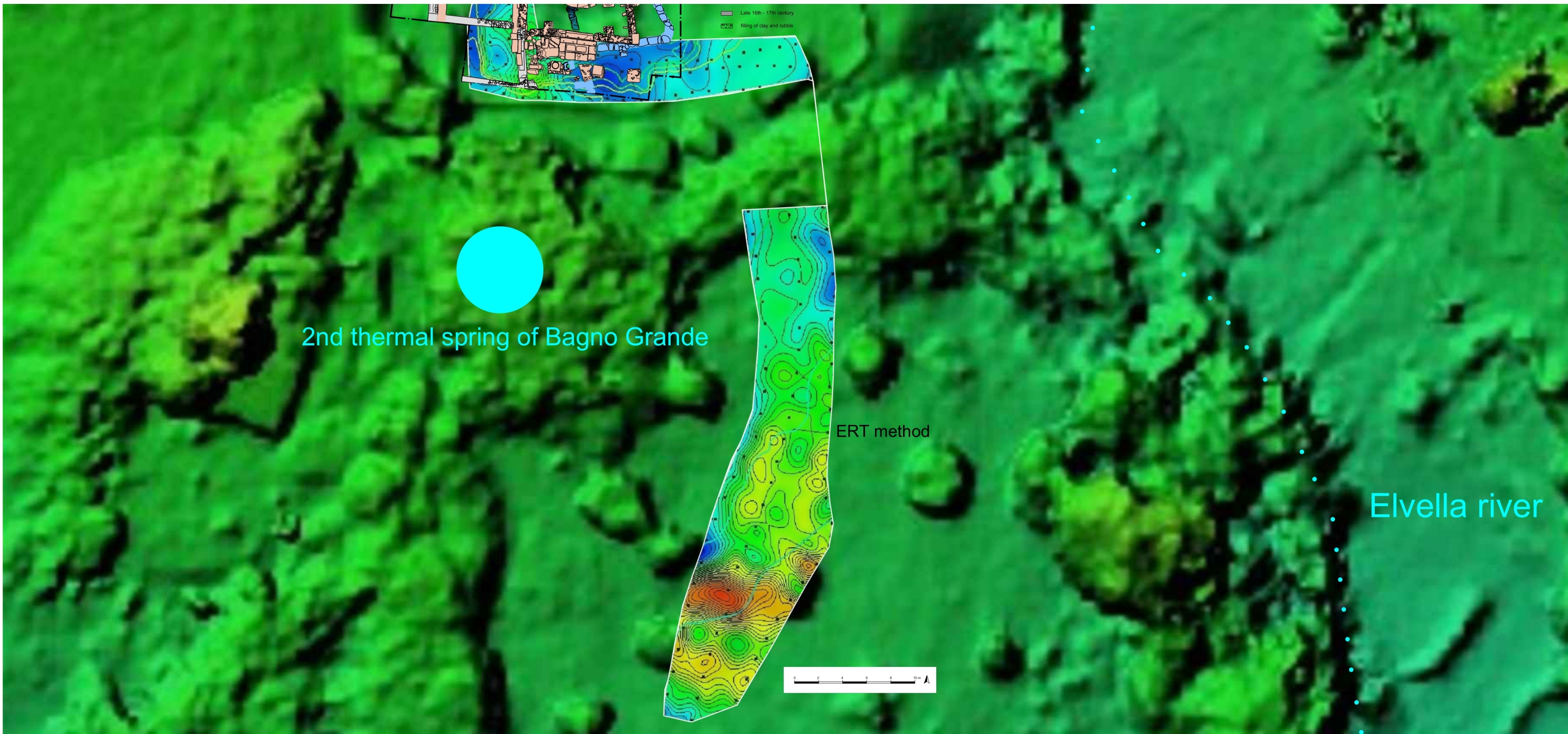

5 | Bagno Grande, southern area: geophysics survey by ERT method and strong red anomaly (Felici, Morelli 2021, graphic processing and interpretation by E. Mariotti).

The area covered by the non-invasive investigations, including the current excavation of the Bagno Grande, is about 3.5 hectares, but the extent of the sanctuary area could be greater, if the other sorrounding springs, named Bagno Bossolo, Fonte di Santa Lucia and Acqua Passante, all located within 300 m, are included.

Archaeological survey activities took place in 2017, with the intention of mapping the evidence on the ground and concentrations of materials in relation to the archival record (Morelli 2014; Fortini et alii 2023, 80-83; Pocobelli 2021). To this phase should be ascribed the identification of some certainly Roman building elements, such as the structure immediately above the spring (Pocobelli 2021; Carpentiero, Felici 2021, 137-138) to which we will return later.

Following this intervention, the first geophysical investigations (magnetometry) were carried out in a large area located about 150 m south of the source of the Bagno Grande [Fig. 03]: the area was chosen because of the conspicuous presence of materials on the surface and because of its location, close to land already placed under archaeological and landscape constraints in 1992 (Carpentiero, Felici 2021, 132). The results, some of which have already been discussed elsewhere, show the presence of numerous anomalies, albeit confusing ones, mainly a sign of a wide dispersion of construction materials, traceable and outcropping even on the ground surface. The greatest concentration of geomagnetic evidence corresponds to the pottery scatters reported by the ground survey itself, although no clear topographical arrangement of the underlying buildings had emerged from either activity. The evidence is located mainly in the eastern part of the investigated area [Fig. 03], along an ideal direction that proceeds southward from the source of the Bagno Grande, following the ground contour: this portion of the area, extending about 1 hectare, is bordered to the east by the Elvella creek, to the north by the area of the springs and adjoining buildings, and to the south again by the river Elvella, although the anomalies are more blurred in this area by virtue of a more clayey subsoil. A sharp demarcation with the western part of the area and slope is evident, as will be seen below.

Further geophysical surveys were carried out between 2019 and 2021, focusing, in particular, around the source of the Bagno Grande (2019 surveys), as indicated by antiquarian sources (Morelli 2014) as rich in archaeological finds, as well as by topographical continuity with respect to the structures emerging from the excavation (2021 surveys). In 2019, two different types of prospecting were carried out, one along the Fontaccia road between the Bossolo Bath and the Bagno Grande, and one in the field immediately east of the spring itself (Carpentiero, Felici 2021, 132-138).

The first saw the use of a georadar, or multi-sensor drag GPR (Ground Penetrating radar), given the regular surface (road), the low amplitude and the instrument's ability to accurately “read” this type of terrain; the second instead used a resistivity meter (ERT, Electric Tomography Resistivity, with electrodes placed on two-dimensional lines), both because of the composition of the soil, in this case clayey, wet (Francese et alii 2018) and subject to agricultural activities, and also because of the course of the same, irregular at the surface and invaded by vegetation. The results can now be read in light of new excavation data that have seen clarification, at least in part, of the architectural development of ancient structures, particularly from the Roman period (Mariotti 2023; Carpentiero, Mariotti 2023; Mariotti et alii 2024). The georadar survey along the road shows, at Bagno Grande, a number of marked anomalies. Some are easily identifiable as hot-water adduction and drainage channels between the spring and the modern pools, already known and visible in their catchment and outlet points [Fig. 04]. Other anomalies, read in the light of subsequent excavations in the adjoining area to the south, are to be identified as the northern part of the recently emerged sacred building: they are located between the present spring and the northern limit of the excavation area, reconnecting planimetrically both with the Roman structures brought to light and with the results of the prospections carried out in 2021, which already indicated unequivocally the extension of the Roman building and its sacred basin toward the spring (Felici, Morelli 2023). The narrow space between the present spring and the Roman building is of fundamental importance for understanding its topographical development, its relationship to the spring itself, as well as the water catchment/adduction systems. The last point is decisive not only from the point of view of historical reconstruction and archaeological or architectural understanding of the structures related to the spring, but also for the management of forthcoming research and excavation activities, where its multi-layering concerns not only the ancient and modern “thermal buildings” (Mariotti 2023b; Tabolli 2023), but also and especially its waters through the hydraulic works of the different periods.

Further insights into the general topography of the area come from the area immediately east of the spring, where, also in 2019, the second prospecting was carried out. The purpose of the survey was to map the possible area of the first exploratory excavation trench, in any case to be located near the spring. The result clearly shows the presence of a major structure in the plateau west of the spring, about 25 m away, perhaps to be read as a podium or basement of some kind, given the width, thickness and homogeneity of the resistive anomaly [Fig. 04]. The evidence remains unknown (an excavation could not be carried out due to the lack of permission from the landowner), but together with the Roman concrete structure now reused as a barnyard animal shelter located immediately upstream of the Bagno Grande (Carpentiero, Felici 2021; Pocobelli 2021), it could be part of the complex topographic mosaic gravitating around the source of the Bagno Grande. These structures remain of uncertain purpose, given also their elevation and location that apparently do not allow for direct use of the waters coming from the Bagno Grande.

Building on the evidence that emerged with the 2020 and 2021 excavation campaigns, additional geophysical surveys were conducted (September 2021), mentioned in part just above. In this case they were concentrated in the excavation area and around the modern pools, with the aim of mapping the extent of Roman structures below the post-Renaissance buildings. The results have been extensively described in recent works (Felici, Morelli 2023; Mariotti 2023a; Carpentiero, Mariotti 2023), as well as having been confirmed by excavation data that see with certainty the continuation of the sacred basin and related structures toward the spring. But what is of interest here is the southern part of these investigations, conducted, again, with ERT (Resistivity Electrical Tomography), a method found to be particularly effective in this context. The southward extension of the geophysics for a stretch of about 50 m [Fig. 05] revealed another rather pronounced resistive anomaly, probably part of a structure. It is not possible to be more precise but a plausible hypothesis is that this evidence is related to the “twin” source of the Bagno Grande, located immediately south of the excavation area, between it and the geophysical anomaly. In this area, the ground slopes steadily southward, making this hypothesis plausible. Canalization works, or additional water management/use basins, also cannot be ruled out, as in other sites of the Roman world (Tölle-Kastenbein 1990; Yegul 1992; Carneiro 2016; González Soutelo, Matilla Séiquer 2017; Bassani et alii 2019; Kušan Špalj D. 2020).

Topography and DEM: the analysis of the ancient thermal landscape through terrain morphology

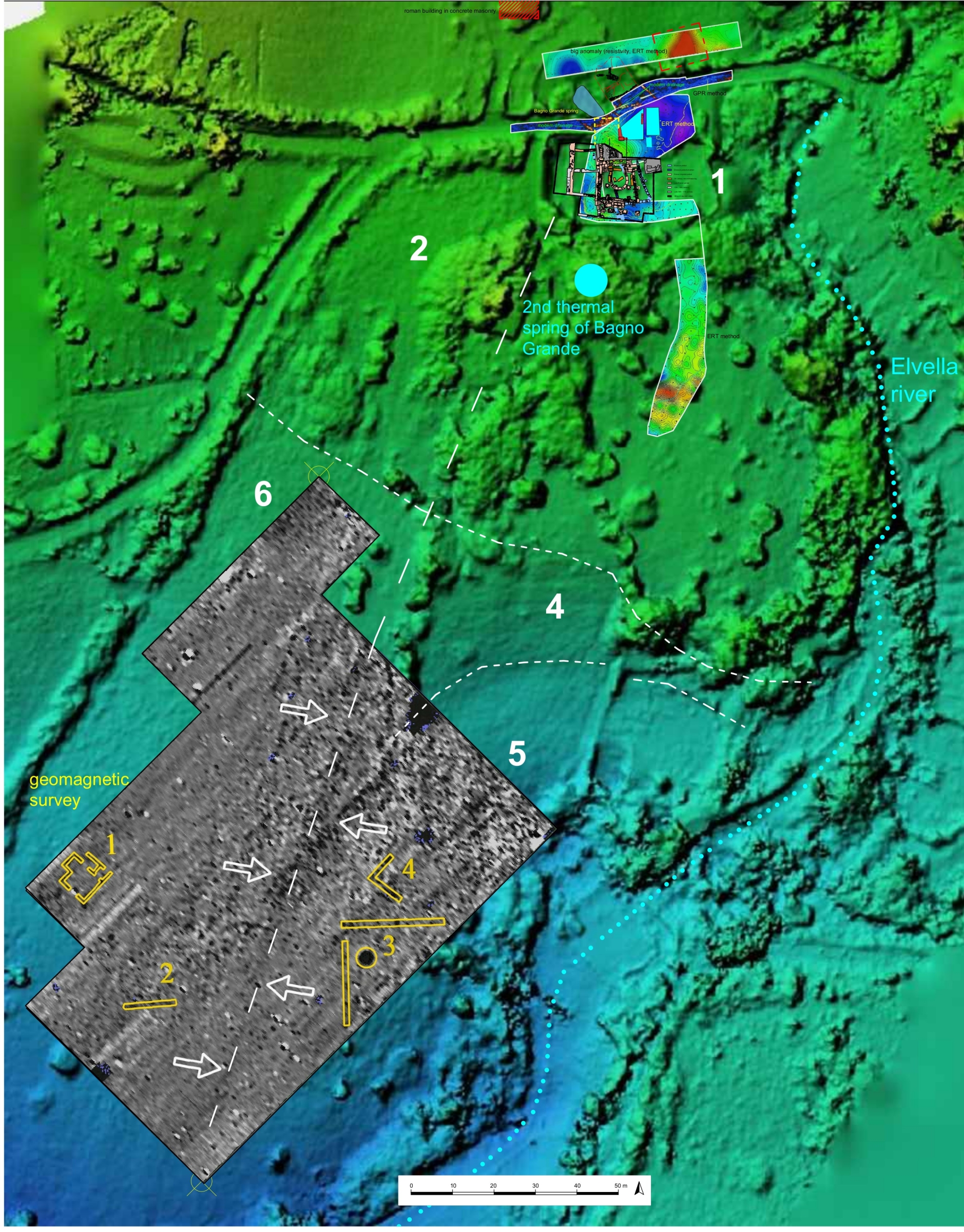

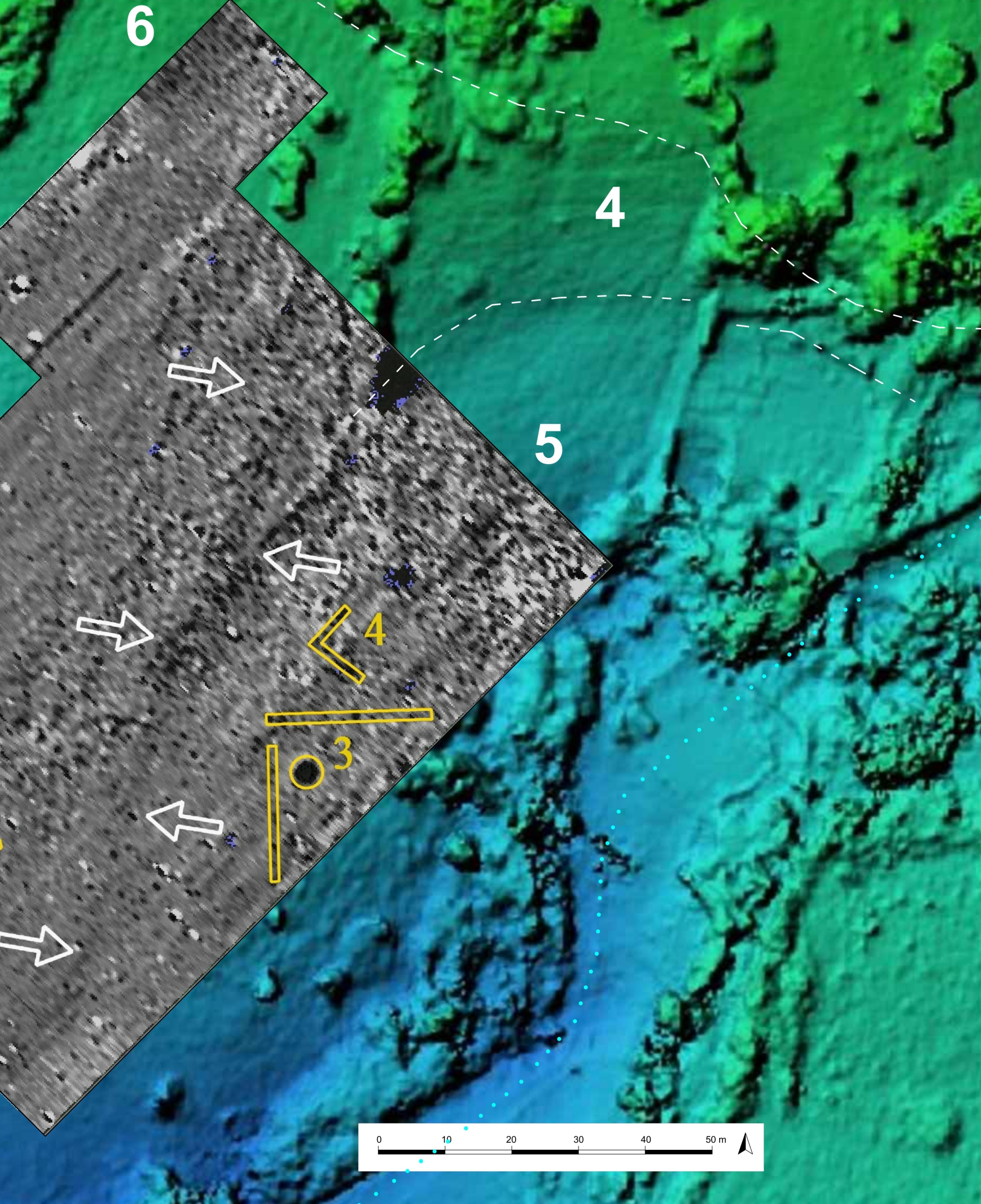

6 | Bagno Grande area: overall geophysics survey overlapping the DEM (graphic processing and interpretation by E. Mariotti).

7 | Bagno Grande, southern area: geophysics survey overlapping the DEM, detail of zones 4 and 5, (graphic processing and interpretation by E. Mariotti).

The analysis of the morphology of the terrain through the creation of a DEM is one of the essential tools of remote sensing in archaeology (Beex 2004; Bitelli et alii 2006; Campana, Forte 2006; Campana, Francovich 2006; Fiorini, Materazzi 2017) and of the analysis of the archaeological landscape in general, understanding this as the outcome of the continuous interaction between anthropic and natural factors (Farinetti 2012). In the area of Bagno Grande this operation is particularly difficult, as already mentioned, especially because of the “environmental fragmentation” that characterizes its territory. The area we are interested in is inhomogeneous, with different uses, different degrees of past and recent anthropization, as well as morphological fragmentation of the land, due to springs and water flow, agricultural interventions with subsequent abandonments, and scattered but at the same time invasive vegetation. For these reasons, the digital terrain model was obtained by combining both aerial photogrammetry from drone and the use of GPS on the ground (Cina 2004).

In analyzing the “shape” of the terrain, two main factors must immediately be taken into account: 1) the spring, as the topographical fulcrum of the area and its archaeological evidence, located at an elevation of about 512 m above sea level; and 2) the Elvella river, which collects the water from the springs and flows immediately downstream from the Bagno Grande. The stream demarcates the area to the east and south, sharply defining the entire area. The spring, located on the northern boundary of the system, marks the starting point around which the identified structures revolve, and from which the waters necessarily had to descend, also determining the destination of possible buildings and spaces depending on their position in relation to the spring itself. Based on the DEM, it was possible to divide the entire area of the Bagno Grande into well-defined zones [Fig. 06]. Zone 2 corresponds to the western area, and it is for the most part at a higher elevation than the spring. It is characterized by a regular plateau immediately beyond the excavation area, the origin of which is probably due to both underlying structures and the large regular burial ground, as shown in Fig. 2. The terrain then descends gradually southward to sector 6, where it increases in slope and then reaches the Elvella River. Sector 6 is characterized by scattering of materials in its central portion at the boundary with sector 5 (Pocobelli 2021), but at the same time it is almost devoid of geomagnetic anomalies, showing a certain uniformity of the subsurface [Fig. 07]. The most evident anomalies, although not well defined, are concentrated toward the east and on the northern boundary of the sector, where elevation jumps could also be determined by structures in the subsurface.

This dynamic is particularly evident starting from the excavation area and from Bagno Grande in general, identified with the number “1”. Sectors 3, 4 and 5 are characterized by a continuous slope to the east and south; they also show outcrops of construction material, including the remains of travertine canalizations: in these sectors, although not extensively and systematically investigated due to vegetation and poor accessibility, geophysical prospecting has yielded unequivocal results.

Magnetometry, although it does not show defined contours of buildings or structures, marks a clear difference between sector 6 and 5, where the presence of subsurface material is clear, most likely washed away, destroyed, and dispersed by human and natural activities over the centuries. Structures must have been present between sectors 4 and 5, and where anomalies are reconstructed [Fig. 07], there are outcrops of caementicium walls, unfortunately not clearly documented due to the abandonment of the fields, invaded by spontaneous vegetation. The separation corresponds to the jump in elevation on the terrain and the presence of a rectilinear anomaly (Felici, Morelli 2023, 25) on which some rows of trees are also aligned: along its direction there are further sporadic outcrops of structures (Pocobelli 2021), until reaching the western limit of the excavation area. At this point, a wall in almost reticulated masonry with the same north-south trend seems to mark the limit of the sacred area (Mariotti et alii Tabolli 2024, 4), perhaps the temenos of the Roman period, at least on this side. Area 3 constitutes a further terrace sloping eastward and southward, immediately downstream from the sacred pool of the Bagno Grande. The area is characterized by a second spring, a strong resistive anomaly as already described immediately downstream of it, a surface strewn with materials, and a regular ground morphology up to its southern limit. The total elevation difference ranges between 511 m a.s.l. at the edge of the sacred building brought to light by the excavation, and 506 m a.s.l. at the southern limit of area “3”.

The transition to zones 4 and 5 represents the major morphological “anomaly” that can be derived from the DEM. A considerable jump in elevation, from 507 m a.s.l. to 495 m a.s.l., characterizes these areas [Fig. 07]: the terrain draws a kind of large arc about 50 m in width, until it reaches the creek limits. Based on the geomagnetic anomalies already described and the structures outcropping just to the south, it seems plausible to interpret this morphology as the result of the disintegration of structures and buildings in the subsurface, which are not yet well defined. It is equally probable, given the geological characteristics of the area, that these buildings took advantage of the natural course of the ground, already sloping in a southerly direction and subject to the flow of copious thermal waters to the stream below.

It is perhaps in these areas that it is possible to locate that oft-remembered “a broad range of facilities”, which had the purpose of welcoming and caring for those who came to the sanctuary, but which nevertheless remains separate from the sacred area proper, if not directly replaced by the latter (Bolder-Boos, Calapà 2019, 116). The problem remains open, and in most cases it is complex to distinguish healing and cult spaces (Renberg 2006; Turfa 2006), although in some cases environments around the monumentalized spring can be read in this direction (Albanesi, Picuti 2009; Chellini 2002, 98-99). As excavations and research continue in the context of the Bagno Grande at San Casciano dei Bagni, it has already been noted how a topographical distinction increasingly emerges between the areas that make up the complex mosaic of this thermal site (Mariotti 2023, 44), at least for the Roman period. If this was considered a simple working hypothesis, based mainly on the characteristics of the architectural structures that emerged, the morphological analysis of the terrain through the DEM tool, seems to emphasize this concept, allowing the identification of very precise areas, distinct from each other.

Although the short duration of the recent excavations has not yet allowed us to bring to light other structures besides the sacred building near the spring, it is reasonable to expect a monumental complex as in the examples of Montegrotto Terme or Vicarello, just to mention two of the best-known contexts (Bassani 2012, 396; Bassani 2019, 9-14) and closer even from the point of view of the extent of the sites. Terrain morphology, contour lines, and vegetation distribution, when read against the backdrop of geophysical data and all other known archaeological evidence, seem to give clear indications as to how the archaeological landscape of Bagno Grande can be read: the area of the sacred springs and the cult spaces connected to them seem to correspond to the areas identified by the numbers “1” and “3”, while further downstream and more distant from the springs, even separated materially from them (Mariotti et alii 2024, 16), must have been the other structures that were public or used for the curative and daily use of the thermal waters. Similarly, Area 2 to the west and the structures immediately above the spring could not have been related to the use of water from the Bagno Grande, precisely because of their location and their higher elevation: the suggestion that we see in these plateaus and raised platforms some sort of temple building remains strong even though not yet proven.

Bibliography

- Albanesi, Picuti 2009

M. Albanesi, M.R. Picuti, Un luogo di culto d’epoca romana all’Aisillo di Bevagna, in “Mélanges d’École française de Rome”, Antiquité 121, 1, (2009), 133-179. - Bassani 2012

M. Bassani, La schedatura dei contesti cultuali presso sorgenti termominerali. Osservazioni preliminari su aspetti strutturali e materiali, in M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae Patavinae. Montegrotto Terme e il termalismo in Italia. Aggiornamenti e nuove prospettive di valorizzazione, Atti del II Convegno Nazionale (Padova, 14-15 giugno 2011), Padova 2012, 391-410. - Bassani 2019

M. Bassani, Shrines and Healing Waters in Ancient Italy. Buildings, Cults, Deities, in M. Bassani, M. Bolder-Boss, U. Fusco (eds.), Rethinking the Concept of ‘Healing Settlements’: Water, Cults, Constructions and Contexts in the Ancient World, Padova 2019, 9-20. - Bassani et alii 2019

M. Bassani, M. Bolder-Boss, U. Fusco (eds.), Rethinking the Concept of ‘Healing Settlements’: Water, Cults, Constructions and Contexts in the Ancient World, Padova 2019. - Beex 2004

W. Beex, Use and abuse of digital terrain/elevation models, Enter the past. The e-way into the four dimensions of cultural heritage, CAA 2003 (BAR IntS 1227), Oxford 2004. - Bitelli et alii 2006

G. Bitelli, V.A. Girelli, M.A. Tini, L. Vittuari, Spatial geodesy applications for accurate georeferencing of Soknopaiou Nesos site and DTM determination, “Fayyum Studies” 2 (2006), 15-22. - Bolder-Boos, Calapà 2019

M. Bolder-Boos, A. Calapà, Cult Places and Healing: Some Preliminary Remarks, in M. Bassani, M. Bolder-Boss, U. Fusco (eds.), Rethinking the Concept of ‘Healing Settlements’: Water, Cults, Constructions and Contexts in the Ancient World, Padova 2019, 115-119. - Boschi 2020

F. Boschi, Archeologia senza scavo. Geofisica e indagini non invasive, Bologna 2020. - Campana, Forte 2006

S. Campana, M. Forte (eds.), From space to place, Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress on Remote Sensing in Archaeology (Rome 2006), Oxford 2006. - Campana, Francovich 2006

S. Campana, R. Francovich, Laser scanner e GPS, Firenze 2006. - Campana, Forte 2010

S. Campana, M. Forte (eds.), Space, Time, Place, Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress on Remote Sensing in Archaeology (Tiruchirappalli 2009), Oxford 2010. - Carneiro 2016

S. Carneiro, The water supply and drainage system of the Roman healing spa of Chaves (Aquae Flaviae), in J.M.F. Garrido, A. Formella, J.A.F. Brea, G.M. Gesteira, F.P. Fermín Pérez Losada, V.R. Vázquez (eds.), Termalismo y Calidad de Vida, Libro de Actas del I Congreso Internacional de Agua Ourense (España), 23-24 de septiembre de 2015), Ourense 2016, 289-298. - Carpentiero, Felici 2021

M.G. Carpentiero, C. Felici, Topografia e indagini non invasive dell’area del Bagno Grande: ricostruzione della viabilità storica e del paesaggio antico di età romana, in Mariotti, Tabolli 2021, 131-144. - Chellini 2002

R. Chellini, Acque sorgive salutari e sacre in Etruria (Italiae Regio VII). Ricerche di topografia archeologica, Oxford 2002. - Cina 2004

A. Cina, GPS. Principi, modalità e tecniche di posizionamento, Torino 2004. - Farinetti 2012

E. Farinetti, I paesaggi in archeologia: analisi e interpretazione, Roma 2012. - Felici, Morelli 2023

C. Felici, G. Morelli, La geofisica del santuario, in Mariotti, Tabolli 2021, 21-27. - Fortini et alii 2023

A. Fortini, M. Ledda, P. Morelli, Senza soluzione di continuità: il Bagno Grande dalla tarda antichità ad oggi, in Mariotti, Tabolli 2021, 71-85. - Fiorini, Materazzi 2017

L. Fiorini, F. Materazzi, Un Iseion a Gravisca? Fotogrammetria, telerilevamento multispettrale da APR e dati archeologici per una possibile identificazione, “FOLDER‐it” 396 (2017). - Forte, Williams 2003

M. Forte, P.R. Williams (eds.), The reconstruction of archeological landscapes through digital technologies, Proceedings of the 1st Italy-United States workshop (Boston, Massachussets 2001), Oxford 2003. - Francese et alii 2018

R. Francese, G. Morelli, F. M. Santos, A. Bondesan, M. Giorgi, A. Tessarollo, An integrated geophysical approach to scan river embankments, “FastTimes” 23 (2018), 86-96. - Giontella 2006

C. Giontella, I luoghi dell’acqua divina: complessi santuariali e forme devozionali in Etruria e Umbria fra epoca arcaica ed età romana, Roma 2006. - Giontella 2012

C. Giontella, «…Nullus enim fons sacer…». Culti idrici di epoca preromana e romana (Regiones VI-VII), Pisa-Roma 2012. - González Soutelo, Matilla Séiquer 2017

S. González Soutelo, G. Matilla Séiquer (eds.), Termalismo antiguo en Hispania. Una análisis del tejido balneario en época romana y tardorromana en la península ibérica, “Anejos de AEspA LXXVIII”, Madrid 2012. - Kušan Špalj D. 2015

D. Kušan Špalj, Aquae Iasae. Nova otkrića iz rimskog razdoblja na području Varaždinskih Toplica. Recent discoveries of Roman remains in the region of Varaždinske Toplice, Zagreb 2015. - MacIntosh Turfa 2006

J. MacIntosh Turfa, Was there room for healing in the healing sanctuaries?, in “Archiv für Religionsgeschichte" 8 (2006), 63–80. - Mariotti 2010

E. Mariotti, Information from the surface: the topographical survey, in S. Mazzoni, Survey of the Archaeological landscape of Ushakli/Kushakli Höyük (Yozgat), “Anatolica” 36 (2010), 111-163. - Mariotti 2012

E. Mariotti, La ricostruzione del paesaggio in ambiente desertico, in B.E. Barich, G. Lucarini (a cura di), Dal deserto al mare. Il paesaggio antico in Egitto, “Scienze dell’Antichità” 17 (2012), Università “La Sapienza” – Roma, 117-138. - Mariotti 2021

E. Mariotti, Il santuario rivelato: gli scavi 2019 e 2020 al Bagno Grande, in Mariotti, Tabolli 2021, 145-170. - Mariotti 2023a

E. Mariotti, Il Bagno Grande nelle campagne di scavo 2021 e 2022, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 29-47. - Mariotti 2023b

E. Mariotti, Il Santuario del Bagno Grande e il suo deposito votivo, in M. Osanna, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Gli dei ritornano. I bronzi di San Casciano, Catalogo della mostra (Roma 2023), Roma 2023, 20-28. - Mariotti, Carpentiero 2023

E. Mariotti, G. Carpentiero, Dal sottosuolo agli elevati: l’architettura del santuario, in Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023, 49-61. - Mariotti et alii 2024

E. Mariotti, A. Salvi, J. Tabolli, Bagno Grande 2023: diachronic and spatial news, “FOLDER-it” 580 (2024). - Mariotti, Tabolli 2021

E. Mariotti, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Il Santuario Ritrovato. Nuovi scavi e ricerche al bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2021. - Mariotti, Tabolli, Salvi 2023

E. Mariotti, J. Tabolli, A. Salvi (a cura di), Il Santuario ritrovato 2. Dentro la vasca sacra. Rapporto preliminare di scavo al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2023. - Materazzi et alii 2024

F. Materazzi, M. Pacifici, F.S. Santaga, From top to bottom Multispectral Remote Sensing and Data Integration to Rediscover Veii, “FOLDER-it” 577 (2024). - Morelli 2014

P. Morelli, Fonti antiquarie, in M. Salvini (a cura di), Etruschi e Romani a San Casciano dei Bagni. Le Stanze Cassianensi, Roma 2014, 76-77. - Morelli 2021

P. Morelli, Il Bagno Grande nella tradizione antiquaria, in Mariotti, Tabolli 2021, 91-98. - Osanna Tabolli 2023

M. Osanna, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Gli dei ritornano. I bronzi di San Casciano, Catalogo della mostra (Roma 2023), Roma 2023. - Osanna, Tabolli 2024

M. Osanna, J. Tabolli (a cura di), Gli dei ritornano. I bronzi di San Casciano, Catalogo della mostra (Napoli 2024), Roma 2024. - Pocobelli 2021

G.F. Pocobelli, Il progetto della Carta Archeologica delle “Acque”, in Mariotti, Tabolli 2021, 121-130. - Tabolli, Mariotti 2021

J. Tabolli, E. Mariotti, Il Bagno Grande tra il 1970 e il 1980: un’inedita collezione, un’inedita ricognizione e un’inedita carta geologica, in Il Santuario Ritrovato 1, Livorno, 99-120. - Tabolli 2023

J. Tabolli, The Etrusco-Roman thermo-mineral sanctuary of Bagno Grande at San Casciano dei Bagni (Siena): aims and perspectives ‘behind-the-scenes’ of ongoing multidisciplinary research project, “FOLDER-it” 556 (2023). - Renberg 2006

G.H. Renberg, “Was Incubation Practiced in the Latin West?”, “ARG” 8 (2006), 105-147. - Summers 2003

G. Summers, The Kerkenes project, “Anatolian Archaeology” 9 (2003), 1-22. - Summers 2008

G. Summers, A Preliminary Interpretation of Remote Sensing and Selective Excavation at the Palatial Complex, Kerkenes, “Anatolia antiqua” 16 (2008), 53-76. - Tölle-Kastenbein 1990

R. Tölle-Kastenbein, Archeologia dell’acqua. La cultura idraulica nel mondo classico, Milano 1990. - Yegül 1992

F. Yegül. Baths and bathing in Classical Antiquity, New York 1992.

The aim of this contribution is to analyse the archaeological topography around the Bagno Grande spring at San Casciano dei Bagni, particularly as regards the Imperial Roman age. Starting from the structures that have emerged in recent years, the area of a large sanctuary that has its focal point in the spring itself and is bordered in its southern and eastern parts by the Elvella stream is increasingly defined. The combined analysis of the visible elements on the ground, the archaeological evidence brought to light, the geophysical prospections and the 3D reconstruction of the terrain (DEM, Digital Elevation Model), makes it possible to propose an initial overall reading of the area, which covers approximately 4 hectares. The morphology of the terrain, based on the geophysical results, appears to be determined by natural and anthropic factors. On the natural terrace sloping down from the source of the Bagno Grande towards the south, structures and different land uses have succeeded one another up to the present day. All of these interventions have contributed to shaping the current surface, which presents, no less, markers such as vegetation and elevation changes, capable of defining different areas, perhaps with different archaeological destinations.

keywords | Digital Elevation Model; San Casciano dei Bagni; Roman Imperial age; Thermal spring.

questo numero di Engramma è a invito: la revisione dei saggi è stata affidata al comitato editoriale e all'international advisory board della rivista

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: E. Mariotti, From DEM to reconstruction of the ancient thermal landscape. Worship spaces and public areas in the context of the Bagno Grande in San Casciano dei Bagni, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 214, luglio 2024, 43-58 | PDF