1 | Photograph by Michael Franke, The Doll's House at MJ Long's House/Studio in St John's Wood, 2018.

This is an account of a doll’s house that came into my possession in 2020. It was designed and made by the British-American architect MJ Long for her young daughter, Sal, in the late 1970s. This object has occupied much of my thinking on work conditions within domestic spaces, explored through its creation and within the knotty themes of gender, women’s agency, and representation[1]. This concern recurs in my work across research, drawing, teaching, writing, and design, where I investigate how the typological development of domestic space and the atomisation and de-collectivisation of productive and reproductive spaces reinforce patriarchal structures.

Doll’s houses are well characterised in this sense, through the ways in which they are encoded with stereotypes of allegedly passive domesticity and gendered play. However, the conventionality of Long’s doll’s house is all the more curious given the backdrop of her other work, ‘office work’, and the ‘real’ domestic space in which much of that work was carried out[2]. This contrasts with the usual representations of women's roles and family in doll's houses, where the miniaturisation of everyday activities and living spaces reveals underlying structures that are, otherwise, not immediately obvious (Chen 2015, 278–295).

Rather than viewing the doll’s house as merely a female-coded or child’s plaything, this paper presents its making as an act of care, knowledge, parody, critique, and resistance—offering the author agency she may not have otherwise found in the world at 1:1. As Matthew Mindrup explains in the book The Architectural Model: Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, the Exemplar and the Muse, women could ultimately manipulate the objects within the house to act out different events of everyday life (Mindrup 2019). In this sense Play, as Nancy R. King discusses, embody an implicit critique of reality and provide an opportunity for people to reflect upon and evaluate the apparent inevitability of existing social relations (King 2015, 320-329).

Starting from the acquisition of the doll’s house at an auction (Palacios Carral 2023), this paper embarks on a journey through my discoveries about its making and the subsequent forms this research has taken, culminating in an exhibition in the autumn of 2023 at the Architectural Association, where the doll’s house was exhibited for the first time as part of her life and work. While play within the nuclear family home sometimes takes place individually and in isolation, as opposed to the playground, for example, or a teenager's collective leisure where ‘their common garb and preferred lifestyle generate a sense of solidarity, and their collective leisure is potentially the basis of an alternative social order’, play within the family home does not always immediately develop as a political activity and, as such, may seem to run the risk of reinforcing the status quo (King 2015, 320-329).

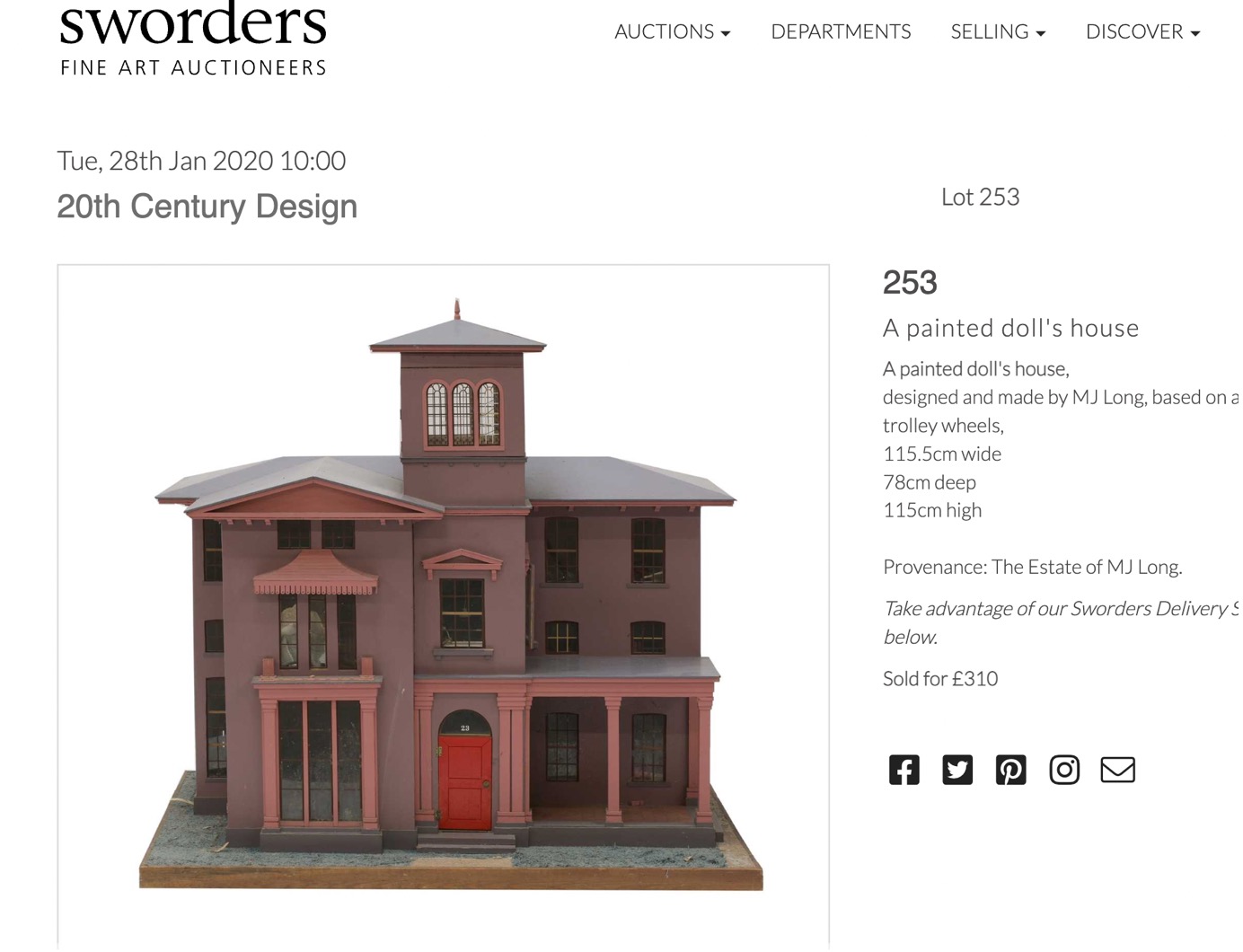

2 | Screenshot of Sworders website showing the doll’s house.

3 | Photograph by Yushi Li, Children’s Bedroom, 2023.

4 | Photograph by Yushi Li, Sal’s Doll’s House Inhabited, 2023.

5 | Photograph by Thomas Adank, AD Doll’s House Reconstruction, 2023.

In MJ Long’s case, I discuss how play (the making of the doll’s house understood here as a form of play) took on a different dimension, creating a space for her to experiment and exercise agency through its making (Chen 2015, 278–295). As will be discussed in the paper, MJ Long’s life was conditioned by the various personas she had to perform, whether she identified with them or not — in the office, in the home, in the studio, in the university, and socially — and the spaces by which such roles conditioned her, all of which are examined through the study and research of this doll’s house she made.

My first view of the doll’s house was via a photograph on an online auction site shortly after MJ Long passed away, where as is typical, the object was clipped from its backdrop, floating on the white pixels of the webpage [Fig. 2]. On first glance, its caption was not much more revealing:

A painted doll's house, designed and made by MJ Long, based on a classic New Haven (US) house, on trolley wheels (MJ Long 2020).

A photograph taken by the artist Michael Franke of Long’s house after her passing, documenting the space of her studio/home as she left it, is featured on the front page of the auction’s website to announce the sale of MJ Long’s estate [Fig. 1]. Amongst the many other objects that furnished her home, the photograph captures the 62 lots that were put up for sale, including the doll’s house. In Franke’s photograph, the doll’s house sits on the floor, underneath the mezzanine and just behind the second piano. In the context of this photograph, it is difficult to discern to what extent the objects depicted for sale were practical, decorative, part of a precious collection, fragments of a design exercise, tools, or perhaps hobbies. Long’s home had served as both a studio and a workspace, blurring the boundaries between the personal and the professional, or the private and the shared. Alongside the Mies van der Rohe chairs, the Alvar Aalto lamp, or the Paolozzi plaster casts, that were listed in the auction, the doll’s house is somewhat of an outlier. It appears banal and quaint with its pitched roofs and belvedere, and I’m not sure it would have caught my attention if it weren’t for the words “designed and made by MJ Long” in the listing.

The doll’s house resists to easy categorisation within Long’s life and work. It couldn’t be considered ‘exemplary’ of her practice or experience as an architect and as a domestic toy I have since learned it found little use. Indeed, the auction house was hesitant to sell it, unsure of how to categorise it in a way that would attract prospective bidders. It was listed in the auction as part of a miscellany of domestic possessions—chairs, books, glasses, and other household objects. Nevertheless, amongst these possessions and in the doll’s house itself, one can start to trace sources of her creative inspiration in these objects that lie beyond their intended function.

My fortuitous acquisition of the doll’s house – mine was the only bid – began a search for the motives behind its construction. During visits to her uncatalogued papers at RIBA, I found an essay she wrote on the development of the villa typology and a series of sketches she made during her trips to Europe of buildings resembling this doll’s house[3]. But it became clear that the doll’s house was modelled almost directly on a real villa in New Haven, close to Long’s alma mater, Yale University. Opening a Google Street view image of Hillhouse Avenue, Connecticut for the first time, I was startled to see the 1:1 building staring back at me. This villa was designed by the early-19th-century architect Henry Austin, and Long's fascination with the building can be traced back to her formative years at Yale, where she had begun her training as an architect.

As such, the doll’s house slowly began to present itself not as a curio, but as a portal into her life and work; as a student, architect, parent, and teacher. It is on one hand a portrait of American life and the importance of family and the home, a reflection of the themes she studied and loved as a student, on the other a manifestation of a form of parenting imbued with her architectural knowledge and references in its making. The products of her career as an architect in Britain are much feted. She co-designed the British Library in the practice she shared with her husband, Colin St John Wilson, taught design at Yale University, whilst establishing another architectural practice from her home called MJ Long Architects, dedicated to ‘smaller’ but no less significant work. Amidst these professional undertakings and raising two children, and during a particularly fraught stage in the design of the British Library, Long committed herself to the construction of this large timber object.

It is a deceptively substantial thing. Constructed at 1:10 scale, it is constructed from plywood cavity walls and floors, its inner and outer faces 8mm thick. Thinner sheets of ply are shaped to form the pitched roofs. Measuring 800mm wide by 1m long and 1m high, it is heavy and requires at least two people to move or carry it. It does not easily fit through standard doorways, and my own tribulations with moving and storing it in the past few years are testament to this. One wonders whether Long considered the dimensions and future transportation of the doll’s house, or if she envisioned it remaining a permanent fixture in her home. Its surface is painted in a colour palette of purple and pink hues with a strikingly bright red front door. Small terracotta tiles mark the portico and kitchen floors, and finely varnished wooden floors line the other rooms of the house. The interior walls are adorned with an assortment of papers mimicking wallpaper [Fig. 3]. MJ Long, with her love for bookbinding and extensive collection of patterned endpapers, repurposed these as wallpaper for the house. As is common with doll’s houses, the back wall is removable, providing a sectional view of the interior space - a method of representation that Long frequently employed in her own architectural design work. Several walls are hinged, resembling cabinet doors, allowing glimpses into hidden corners of the house [Fig. 4].

A doll’s house, unlike the architect’s working model, retains a sense of permanence. Architectural models are often made of cardboard, paper and foam (For a discussion of physical architectural models and the choice of materials used in their making see Mindrup 2019). They are cut into, edited or thrown away, but doll’s houses are more robust, solid objects, perhaps to endure the weathering effects of time and play through different generations (See discussions around this in Palacios Carral, Kentish, Synek Herd, Verghese, Jennings 2023). In the nineteenth century, they were used as teaching tools for cultivating ideas about moral order and taste in young women who would one day keep and furnish their own houses (Mindrup 2019).

But while Long was certainly not making a direct replica of her home, as 19th-century doll’s houses often were, houses within houses, nor intending to instruct Sal on how to be a woman or furnish her future home, this doll’s house was made to last. Sal remembers her mother spending late hours after work building the doll’s house on the floor of their living room. She particularly recalls her building the base of the doll’s house, intended to be the garden, using green towel to mimic the grass. Between acquisitions sourced from a local corner shop in London, the doll’s house is furnished with a plethora of handmade miniatures - carpets that she hand-weaved, a miniature dictionary she authored and illustrated, beds she meticulously crafted. Other furnishings were picked up on various trips abroad, a rocking horse from East Germany, pots and pans from India, whilst the paintings that hang on the walls of the doll’s house are diminutive facsimiles of Long and Wilson’s own extensive art collection which included work by Peter Blake, Howard Hodgkin and RB Kitaj. So not a replica of her home in the 19th century tradition, but certainly a physical mirror of aspects of Long’s life and career.

Sal was the client for the doll’s house, yet many references, objects, and stories within the project suggest it was more an object for Long herself. Apart from the request to have ‘granny’ live in the belvedere and an unusual brief to have the stairs landing directly into the bath, Sal made no other demands or directly influenced the design of the doll’s house. As such, perhaps, the doll’s house saw little use as a child’s plaything. Yet the labour Long poured into its construction strongly suggest the endeavour bore some other meaning for her. She had founded MJ Long Architects, to work, as she stated, on smaller projects compared to those she undertook in the office she shared with her husband, which one would think might provide ample ‘extra-curricular’ work. United with the prominent position that she held at one of the most significant offices in Britain at that time, and her tenure across the Atlantic at Yale, her work on the doll’s house seems all the more startling. She would work late into the night on it, the templating drawings for its walls and floors scribed over British Library drawing sheets. Rolfe Kentish, a colleague who would later become her business partner after Wilson’s death, recalled a ferocious work ethic and commitment to each of her roles, often retuning from long haul flight with bundles of sketches for the office. Sal recalls her mother setting up the drawing board in the kitchen after dinner to work late into the night[4] . As controversy rumbled on over the design and construction of the British Library – which in its entirety took around 30 years to complete and to which Long’s contribution is repeatedly overlooked – it is hard not to embrace the notion that the doll’s house may have come to represent a project that she could see from beginning to end.

The agency she could command with such a project could be seen at odds with her professional career at that time. Despite her contributions, she has, by virtue of her marital status or gender, been overshadowed by her husband’s name. Presently, the archive of Colin St John Wilson Architects, is being catalogued by the RIBA. Whilst this endeavour is valuable, her work within that practice is at risk of being overwritten, in some cases literally. Meanwhile, her personal papers and collection remain in brown storage boxes at RIBA, uncatalogued and without a long-term plan for their safe stewardship. The doll's house Long built for her daughter Sal is not part of this collection, nor are other personal papers donated to the RIBA.

The exhibition I designed and curated at the Architectural Association at the end of 2023, Portraits of a Practice thus serves as a pretext and an opportunity to formalise the research I had been developing, secure funding, and advocate for the recognition of MJ Long’s collection and work on her own terms. The doll’s house took centre stage in the exhibition as opposed to the plethora of other items that typically dominate discussions of an architect's work in academic or professional circles. In this sense, to showcase the doll’s house — an object she crafted within the confines of her home, and one that didn’t find its way into her uncatalogued collection at RIBA — is to assert a demand for recognition and challenge the prevailing status quo.

In the exhibition, another doll’s house was displayed [Fig.5]. This second house, often colloquially referred to as the AD Doll’s House, was designed by MJ Long in 1982 as part of Colin St John Wilson and Partners’ entry to a competition organised by Andreas Papadakis, the editor of Architectural Design (AD) magazine. It received third prize. As such, and unlike Sal’s doll’s house which was an object only known within the family and the context of her home studio, the AD Doll’s House was designed within the setting of the office she shared with her husband. A series of photographs in the family archive show Sal playing with the AD doll’s house as part of an interview for the BBC. In contrast, there are no photos of her playing with the one her mother made for her, only a series of photos MJ Long took of the furnished doll’s house.

The AD doll’s house entries were also auctioned for charity in 1983 at Sotheby's, but the current whereabouts of this doll’s house are unknown. Since the original AD house was lost, I commissioned a designer, Isabella Synek Herd, to create a replica from archived drawings, photographs, and sketches of the original design. She received guidance from Rolfe Kentish, who himself was involved in the construction of the original. A collaborator of MJ Long’s, Kentish would later enter into a formal partnership with her under the office name Long and Kentish Architects. Isabella constructed the replica during the summer of 2023 in the AA’s workshops, working to match the finishes, mechanisms, and dimensions of the original as closely as possible, whilst also incorporating updated digital technologies such as laser cutting and CNC, as described by Isabella Synek Herd.

The AD house is similar in form and function to the one Long made for her daughter, and bears traces of her friendships and relationships with other significant architects of the time. Reuniting these two doll’s houses — one made at home and the other in the office — encourages us to question the parallels and distinctions between an architectural model and a doll’s house (Palacios Carral, Kentish, Synek Herd, Verghese, Jennings 2023). The conditions of their making were radically different, but there are clear overlaps between the two. In fact, Long worked on the two doll’s houses almost contemporaneously, and her uncatalogued papers at RIBA reveal the connections that exist between them. A series of early sketches that MJ Long drew of the AD doll’s house show her using elements from Sal’s doll’s house to furnish and inhabit the drawings. Whilst the inhabitation did not make it to the final competition boards – Rolfe explains that the lack of furnishings was intentional, for fear of imposing a sense of play that sometimes comes with the specificity of certain objects or the miniaturisation of people – it remains part of the process within the archives and catalogues as part of the Colin St John Wilson’s collection. It’s only when viewed next to Sal’s house do we understand these small but crucial mischaracterisations. Moreover, certain motifs such as arches, windows and the spatial diagram of the villa are visible connections between the two doll’s houses, but the AD doll’s house appears as a radical reconfiguration of a typical villa layout – where its levels are made ambiguous, and connections or relationships are made through a central structuring core that ties various rooms together.

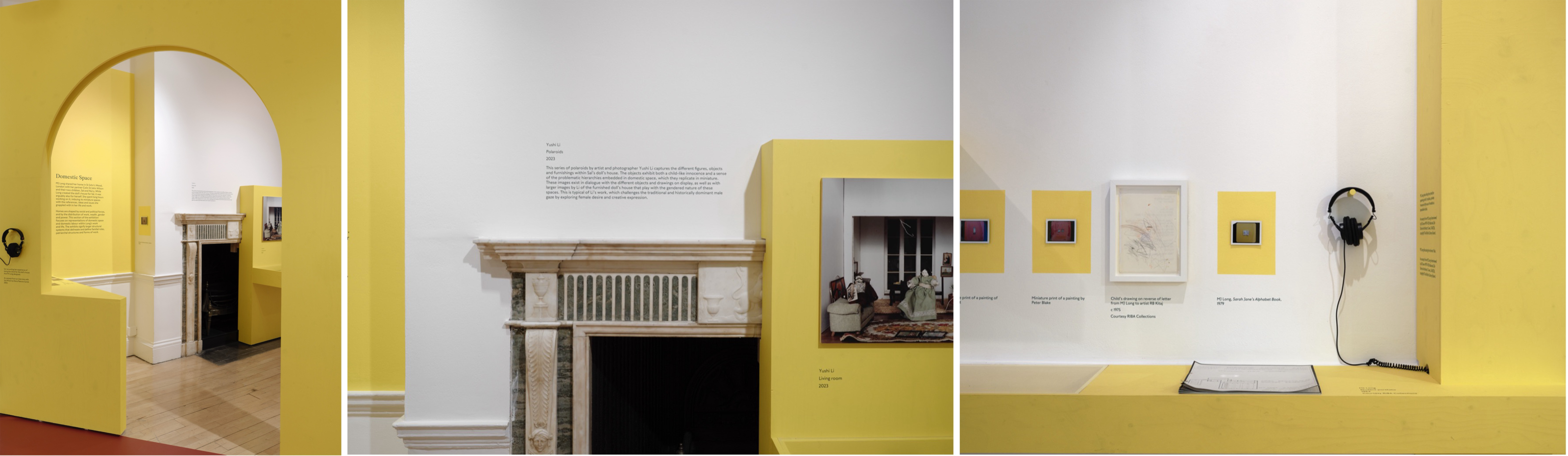

6 | Photograph by Thomas Adank, Exhibition design showing the arches that negotiate the transition between the studio and the domestic space in the exhibition, Portraits of a Practice: The Life and Work of MJ Long, Architectural Association, 2023.

7 | Photograph by Thomas Adank, Exhibition design showing the dialogue between the Georgian domestic architecture of the gallery at the Architectural Association and the exhibition design, Portraits of a Practice: The Life and Work of MJ Long, Architectural Association, 2023.

8 | Photograph by Thomas Adank, Exhibition design showing child’s drawing on reverse of letter from MJ Long to artist RB Kitaj, Portraits of a Practice: The Life and Work of MJ Long, Architectural Association, 2023.

-

9 | Photograph by Thomas Adank, Exhibition design capturing the uninhabited doll’s house and the belvedere, Portraits of a Practice: The Life and Work of MJ Long, Architectural Association, 2023.

10 | Photograph by Thomas Adank, Exhibition design showing Yushi Li’s photographs on display, Portraits of a Practice: The Life and Work of MJ Long, Architectural Association, 2023.

11 | Photograph by Yushi Li, Broken Bathtub, Polaroid, 2023

The exhibition featured fragments that could be assembled into three sections that correspond to MJ Long's house/studio, her office at Colin St John Wilson and Partners, and her domestic space [Fig.6]. These divisions were made in dialogue with the Georgian domestic architecture of the AA Gallery, but they were specifically not intended to establish any rigid boundaries or reinforce the hierarchies inherent in different spaces of her work. Instead, the purpose of the design was to emphasise the overlaps between these spaces and their use, while unveiling the layers within them that otherwise remain hidden [Fig. 7]. These layers encompass everything from the repeated arches visible in both doll’s houses and the architecture of Long’s home, to her children’s scribbles on the back of a letter she was drafting to the artist RB Kitaj [Fig. 8].

Sal’s doll's house is not displayed with its contents [Fig. 9]. Instead, these objects are dispersed throughout the exhibition creating conversations and adjacencies with materials drawn from her archive. A series of photographs were commissioned by the artist Yushi Li, showing Sal’s doll’s house furnished as she remembered it and distributed across the exhibition space [Fig. 10]. In addition, Li took a series of polaroids that capture the different figures, objects, and furnishings within Sal’s doll’s house [Fig. 11]. The objects exhibit both a child-like innocence and a sense of the problematic hierarchies embedded in domestic space, which they replicate in miniature. These images exist in dialogue with the different objects and drawings on display, as well as with larger images by Li of the furnished doll’s house that play with the gendered nature of these spaces. This is typical of Li’s work, which challenges the traditional and historically dominant male gaze by exploring female desire and creative expression (see Yushi Li’s work here).

Homes are shaped by social and political forces and by the distribution of work, wealth, gender, and power. They signify larger structural systems that delineate and define familial roles, patriarchal structures, and forms of work. Doll’s houses typically draw on these political forces that are reinforced or resisted through active play. MJ Long's home, which she referred to as her ‘house/studio’, making emphasis to the role of her home as a space of production and reproduction, a site of perpetual work. It was the home she shared with her family as well as the address of her independent practice, MJ Long Architects, whose projects included several artists’ studios – ‘house/studios’ in their own right. She worked throughout her carrier as an architect, trying to negotiate the conditions of living and working that conditioned her own existence as displayed in the studios she designed. The domestic and intellectual spheres of Long’s life overlapped in her house/studio, highlighting that the home is a space of work where domestic labour is rendered invisible, mirroring how Long was at times made invisible in her architectural work.

Special thanks to Isabella Synek Herd, Sal Wilson, Rolfe Kentish, Manijeh Verghese, Harriet Jennings and Jon Lopez.

Notes

1 | For a study of the relationship between domesticity, gender and work see the work of the architect and scholar Maria Shéhérazade Giudici. Especially the essay: Giudici Aureli 2018. Other brief selection of relevant work discussing this relationship are: Cavallero, Gago, Mason-Deese 2024; Rendell, Penner, Borden 2000; Hayden 1981; MacDowell 1999.

2 | A few examples of feminist and queer theorists discussing the home as a space of work are: Angela Davis, Silvia Federici, Sheila Rowbotham, Ann Oakley, Arlie Hochschild, Maria Mies, Judith Butler, Sarah Ahmed, Kathi Weeks and Jack Halberstam. For an architectural study of the relationship between living and working see: Holliss 2015.

3 | The original essay is currently in storage at RIBA as part of MJ Long’s uncatalogued collection. The essay was a submission of student work by Long in 1961. The essay is titled: Long 1961.

4 | In private conversations both Sal Wilson and Rolfe Kentish recall MJ Long working all the time. They share the same memory of her working in a drawing board in the kitchen of her home late at night.

References

- Cavallero, Gago, Mason-Deese 2024

L. Cavallero, V. Gago, L. Mason-Deese, The home as laboratory: Finance, housing, and feminist struggle, New York 2024. - Chen 2015

N.WN Chen, Playing with Size and Reality: The Fascination of a Dolls’ House World, “Child Lit Educ” 46 (2015) 278–295 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-014-9234-y). - Giudici, Aureli 2016

M.S. Giudici, P.V. Aureli, Familiar Horror: Toward a critique of Domestic Space, “Log” 38 (2016), 105-129 (http://www.jstor.org/stable/26323792). - Hayden 1981

Dolores Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities, Cambridge (MA)-London 1981. - Holliss 2015

Frances Holliss, Beyond Live/Work: The Architecture of Home-Based Work, London 2015. - King 1982

N.R. King, Children’s play as a form of resistance in the classroom, “The Journal of Education” 164, 4 (1982), 320-329 (http://www.jstor.org/stable/42772854). - Long 1961

MJ Long, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Italian Villa Style, “History of Art” 53b (10 May 1961). - Mac Dowell 1999

Linda MacDowell, Gender, Identity and Place, Cambridge 1999. - Mindrup 2019

M. Mindrup, The Architectural Model: Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, the Exemplar, and the Muse, Cambridge (MA) 2019. - MJ Long 2020

From the estate of MJ Long, designer of the British Library, Sworders Fine Art Auctioneers, 2020 (accessed 30 May 2024). - Palacios Carral 2023

E. Palacios Carral, MJ Long’s Doll’s House, “Drawing Matter” (31 March 2023). - Rendell, Penner, Borden 2000

J. Rendell, B. Penner, I. Borden, Gender space architecture, London 2000.

MJ Long, a British American architect, mother, partner, and teacher, juggled multiple roles throughout her career. At its peak, she designed the British Library, taught design at Yale, and ran a practice from her studio/house focused on smaller but no less significant projects. Amidst these commitments and raising two children, Long also built a large timber doll's house for her daughter during a challenging phase of the British Library project in the late 1970s. Despite her achievements, her work has often been overshadowed by her husband's name. While the RIBA is cataloguing the archive of Colin St John Wilson Architects, which she co-directed, her personal papers remain uncatalogued. The doll's house, not included in the RIBA collection, was auctioned as a, and amongst, domestic items after her death. My research, including a 2023 exhibition at the Architectural Association, explores the doll's house as a junction of Long's influences and roles. It challenges gender stereotypes, presenting the doll's house as an act of care, knowledge, parody, critique, and resistance, offering Long agency she may not have found in the 1:1 world.

keywords | Doll’s house; MJ Long; Studio-house; Domesticity; Play.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: E. Palacios Carral, Making a Doll’s House, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 213, giugno 2024, pp. 151-163 | PDF