Sticker Album for a New Mythology

Kaos – A Netflix Series (2024)

by Engramma Board*

Abstract | Versione italiana

A Presentation

What is Kaos?

As discord reigns on Mount Olympus and almighty Zeus spirals into paranoia, three mortals are destined to reshape the future of humankind. This is the synopsis that appears on the site of the Netflix platform, introducing the series Kaos, conceived and written by Charlie Covell, structured in eight episodes of less than an hour each. The series has beeen released on Netflix channels in August 2024.

Described as a “mythological dark comedy”, Kaos puts myths back into action in a mixed world of the present, classical and archaic, where deities and humans share hierarchical bonds and prophecies in varying degrees, foreshadowing the victory of entropy in all areas of nature and relationships. The prophecy, which reappears in different forms in different worlds – Olympus, Earth, and Hades – reads: “A line appears / The order wanes / The family falls / And Kaos reigns”. The young poietés of the story is Charlie Covell, who had already written the disturbing series The End of the F***ing World in 2017. The publication of Kaos was accompanied by several interviews in which Covell attempted to reveal his sources (see in particular Lydia Venn, Kaos creator on Greek mythology icons, hidden meanings and season two, “Cosmopolitan”, 29 August 2024). In them, Covell describes himself as “a massive nerd who was obsessed with the original Clash of the Titans film’”(Desmond Davis’s film – USA, UK 1981 and Louis Leterrier’s film – USA 2010 – are based on the story of Perseus). In Covell’s library, the illustrated mythology books that give shape to the gods and heroes of Greek mythology coexist with powerful reinterpretations by writers such as the Canadian Margaret Atwood, with her novel The Penelopiad (2005), or the Scottish Carol Ann Duffy, whose collection The World’s Wife (1999) also features an extraordinary Eurydice, who leaves her mark on Covell’s imagination and is a source of inspiration for Riddy in Kaos. Covell’ first work, entitled Clytemnestra, dated back to 2009, and the idea of a Zeus struggling with a mid-life crisis, when the formation of a wrinkle/line on the skin brings with it the threat of the collapse of an entire universe, begins to emerge.

The Kaos album

Now that Netflix has announced that the second season of the TV series Kaos will not be produced, and thus the interweaving of stories in the parallel time that mixes the Olympic gods and the contemporary world will not continue, the first part with its eight episodes is all the more set up as a world in vitro. A bubble of temporal levels, a collage of terrestrial and otherworldly geographies in which the absolute protagonists move: the myths. They inhabit a pantheon with a few fixed points (the arrogance and caprice of Zeus; the fluid power of Poseidon; the incomparable profile of Hera) and many subtle renegotiations of ancient versions of myth. Consider Persephone’s startling outing in episode 8: “Why the story? About me and Hades […] Get it in all the human books. You know? Every kid on Earth, when they learn about the underworld, they think I’m there against my will. They pity me. They think I was kidnapped, raped, in some cases. And a pomegranate… I don’t eat pomegranate. I’m allergic. They think I don’t love Hades. Never did”. When Dyonisos asks: “Wait, is that not true? You love my uncle for real?” Persephone answers: “Yeah”.

Charlie Covell, who conceived the series by drawing on sources with an unprecedented creative synthesis, has delivered to the present day an album of myths that span the ages. And they require a serious game: to fill the album with figures, to follow the metamorphosis of the character from his ancient face, through the centuries, to the present imagination. And, as always, the more you know, the more you enjoy the connections and gaps between ancient sources and new revelations.

Our game, the game-within-a-game that we propose on this page, is based on a precise philological and iconographic scheme: the new figures of the myth are sifted through the ancient sources in order to trace the affinities and ruptures between the vast corpus of writings and figures handed down through the centuries by the classical tradition and the flicker of contemporary incarnation by actors and actresses who, guided by a brilliant vision, revive myths in bodies that are contemporary with us.

From the Baroque Maniera, the Kaos-heim

Kaos series posters revised by Netflix’s communication.

Disseminated via social media platforms (Instagram, X, Facebook), the posters created for the series make explicit references to mythology, refracted through a lens of strong actualisation that remains inseparable from the lexicon of the late Renaissance mannerism. Indeed, all the protagonists – gods and men alike – are depicted with their iconographic attributes and in their theatrical costumes, as they appear to emerge from the architectural breakthrough of a Baroque ceiling.

The author of the advertising shoots is David Lachapelle, who reinvents the gods within the context of contemporary Hollywood kitsch. On the artist’s promotional website and via the social channels of communications agency Creative Exchange, ‘paintings’ will be published showing each character surrounded by their respective iconographic attributes. Lachapelle’s gaze is enthusiastic, drawing on the fascination that Greek mythology held for him during his school years: “I remember being obsessed with Greek Mythology in high school. I knew all the characters and their complex relationships, so the idea of bringing them into modern times was exciting for me”. The style choice of depicting gods and humans follows the artist’s idea that the two worlds are connected but fundamentally separate, and this separation is highlighted by the display of luxury: “The dichotomy between the worlds of the Gods and regular people is so relevant to our society today. The Gods are like the élite class, the 1% living these privileged lives and looking down the rest of humankind struggling to buy groceries”.

To coincide with the release of the series, on 29 August 2024, a series of glossy images of each character was published online (Kaos’ Dionysus is the cover image of this issue of Engramma); The square with the architectural breakthrough is perhaps a later collage (Lachapelle and the Creative Exchange agency make no mention of it on their social channels) and anticipates, in a frame decorated with faux stucco and phytomorphic motifs, some thematic junctions of the narrative, isolating the “stickers” with the main characters.

The poster for the Netflix series already makes explicit the polarity that will alternate between human and divine events in the dramaturgical development. The mannerist structure that accompanies many iconographic choices of the series is also evident in the poster. The four clypeuses in the corners of the composition, partly in grisaille, represent the symbols of the male and female that oversee the realms of the living and the dead: at the bottom, the pomegranate (Persephone) and the skull (Hades); at the top, a bee (Hera) and a clock (the Casio of the Chronid Zeus). The latter in particular – a gold-plated vintage Casio (not yet gold) with a commercial value of less than a Netflix subscription – anticipates the constant shift between elegant contexts and cultured quotations and low, tawdry displays, all appearance and little substance, that pervades the gods in the series. It is on these assumptions that the particular versions of the Olympian hypostases that appear in Kaos are based, as are the profiles of the human beings involved in the plots of the divine whims. The poster of the series also presents itself with a double perspective: it conveys the inverted image, placing now the humans (Riddy, aka Eurydice), now the gods (Zeus) at the centre. Let’s consider the gods first: at the centre of the mock ’baroque’ frame, with swirls of plants, folders and fake composite columns, appears Zeus (Jeff Goldblum), dressed in the shabby chic of the latest – very expensive – designer label, his left hand displaying the incandescent energy of the spark of fire, ready to be hurled with exhibited sprezzatura. In the background is Olympus: a gaudy classical villa with pronaos and tympanum on display. Next to him are his sister Hera (Janet McTeer) and brother Poseidon (Cliff Curtis); the former, dressed in silk and surrounded by rose bushes, in a sophisticated and refined elegance; the latter, proud of his golden trident, smoking a cigar with his shirt open on a gaudy (and tacky) necklace. On either side, in a central position, are the other Olympians: Dionysus (Nabhaan Rizwan) on the left, Hades (David Thewlis) and Persephone (Rakie Ayola) on the right, all accompanied by the distinctive elements of their iconographies, grapes and a cluster of skulls. And here we come to the end of the figures of the deities who have been summoned as the cast of Kaos (at least in this first series): major absentees from the canon of the twelve Olympian gods are Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hephaestus, Hermes, Demeter, who never appear in the dramaturgical development (except in a fleeting allusion in the message left by Zeus on the answering machine of the children who do not answer his calls: “Uh, Apollo […] it’s Dad; Hello, Aphrodite. It’s Daddy […]; Artemis? This is Papooza”). Conspicuously absent from the campaign posters is the image of Prometheus (Stephen Dillane), who is the narrative voice of the series.

Turning the image around, the iconographic pattern repeats itself: in the centre is Riddy (Eurydice, Aurora Perrineau), dressed informally (rolled-up trousers and T-shirt), trampling contemptuously with her Birkenstocks (the ‘classic’ Arizona model, the same chosen by Barbie/Margot Robbie to emancipate herself from Barbieland and enter real life), the divine herms defaced by coloured bombs, whose blows destroyed the statues, but not Riddy. Beside her, on the right, are her unloved husband Orpheus (Killian Scott) and the young would-be president Ariadne (Leila Farzad); on the left, Ceneus (Misia Butler) in his work uniform (in Kaos, he works for Hades’ organisational team), accompanied by his trusty Cerberus. In the background, the courtly atmosphere of the Olympians becomes apocalyptic: funeral pyres, ruins, and corpses.

Lachapelle’s reinvention is thus reworked through the expedient of the architectural frame, highlighting a reappearance of myth that draws heavily on the imagery of the manner. It is in fact a Zeus Oratrios, who stands out on the advertising poster, similar to the protagonist of the composition in the Sala dei Giganti in the Palazzo Te in Mantua, where Giulio Romano portrays Jupiter at the centre of the architectural breakthrough. In this context, too, the canon of the Olympians, already celebrated by Raphael with The Council of the Gods (in the ceiling fresco of the Loggia of Psyche at the Villa Farnesina in Rome, in which a young Giulio Romano collaborated), is revisited, but the king of the gods is given a central role.

About the scenarios: Lachapelle vs. Grant Wood

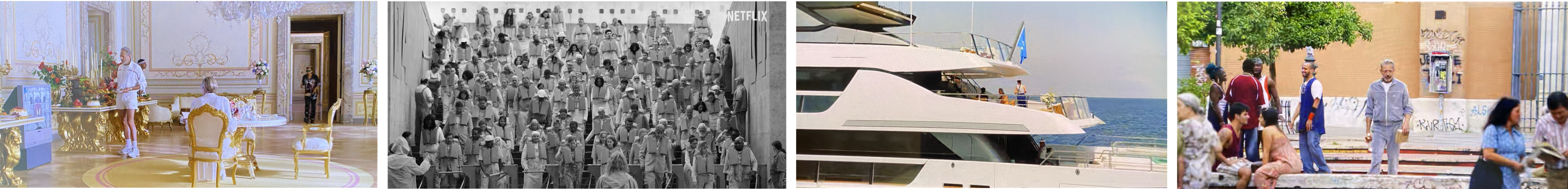

The realms of Olympus, Hades, the sea and the earth in Kaos (Netflix 2024).

From left to right: an interior scene in Olympus, with Zeus in a tennis outfit; a scene from Hades; the Sea Kingdom, seen from Poseidon’s yacht; the vibrant and colourful Earth, with Zeus visiting mortals.

The realms of the gods are quite distinct in mythography: Zeus rules over the sky and earth, Hades over the underworld, and Poseidon over the waters. In the imagery evoked by Charlie Covell, Hades is the place that visually stands out most in its achromatism. The use of black and white surrounds and overwhelms all those who inhabit the realm of death: it is another context, devoid of the colour of life. The realm of Hades is not gloomy and dark as in Dante’s imagery, but simply colourless: everything is flattened in a ‘brutalist’ architecture where even luxury appears dull and resigned. Everything has a whiff of real socialism about it : the uniforms, the rooms, the offices, and the canteen, complete with bunkers where concrete is the protagonist.

The Olympus could only be a mannerist villa. The double set of the Reggia di Caserta and the Villa d’Este at Tivoli – with its fountains and gardens – are the framework within which the ‘royal family’ moves; the interiors, cluttered with mirrors and stuccoes and furnishings of dubious taste, wink at Hollywood villas where gold, light and kitsch are the masters. The realm of Poseidon stands out little in the imagery of the series: the luxury of Olympus is translated and contained in the form of a yacht for rich people, not even particularly luxurious and showy.

If the imagery conveyed by Lachapelle’s promotional images can easily be traced in the furnishings and habits of Zeus’s abode (where even the servants are dressed as swanky luxury club ball-catchers), the realm of Hades is linked to the poetics of another American artist: Grant Wood. A protagonist of verist realism in the USA, the painter is known for an oil on canvas dated 1930 and preserved at the Art Institute of Chicago: American Gothic. It is the precise iconographic model recovered for the appearance of Hades in Kaos Man with a straw hat and round spectacles, as is stated in a scene in the penultimate episode of the series where, in the chamber of the god of the underworld, a copy of Wood’s painting hangs, obviously turned to black and white.

In the earth, the world of humans – lively and colourful and for this reason frequented by Dionysus and envied by Zeus – Minos rules (not reigns!), depicted as a militaristic dictator. The setting could only be that of a modern seaside resort, for which the choice fell on Andalusia. Instead, Zeus’ incursion into the world of mortals, to spy with surprise on their (our) senseless and unmotivated joie de vivre, is set in Rome, in the San Lorenzo area, between Piazza dell’Immacolata and Sapienza University, where Arturo Martini’s Minerva dominates.

ap & as

Sticker Album

Cassandra

from left: Clytemnestra kills Cassandra, kylix 5th century BC; Ferrara Archaeological Museum; Evelyn De Morgan, Cassandra, oil on canvas, 1898, London, De Morgan Collection; Cassandra (Billie Piper) in Kaos, Netflix 2024, Episode 1.

In ancient iconography, from the Archaic Age to Pompeian painting, Cassandra appears in two episodes of her mythical story: the rape, after the fall of Troy, by Ajax Oileus (the first source is Arctinus apud Proclus, Chrest. V, p. 108, ed. 108, ed. Allen); her murder by Clytemnestra (a representation of this episode is on a bronze plate from the 7th century BC Heraion of Argos; one on the kylix of Ferrara reproduced above; the earliest sources are Odyssey XI, 395-396; Pindar Ol. XI, 28 ff.). The new profile that Aeschylus gives to the character in the Oresteia is important: in Agamemnon, the king of the Achaeans, on entering the palace, declares that he has taken Priam’s daughter for himself as the ‘exquisite flower of the spoils of Troy’ (Ag., 954-955). Cassandra then recapitulates her story in the long episode that lies at the centre of the tragedy, in which she is the protagonist, without mentioning the episode of Ajax’s rape. The emphasis is all on her prophetic inspiration, and the fact that she is destined never to be believed is the bad gift that Apollo gave her because she did not allow herself to be seduced by the god. One passage in the tragedy seems to be important for the construction of Kaos’ character: “My parents, my loved ones? No! They were all my enemies. I made true prophecies, but in vain, it was no use. I was humiliated, treated like a madwoman, a charlatan: lousy, miserable, starving… I endured it all” (Ag., 1270-1274).

After a thousand-year slumber, Cassandra reapparaed at the beginning of the 15th century in Christine de Pizan’s La Cité des Dames among the heroines who inhabit the castle built by Dame Rectitude (II.V). Her image reappears in the Pre-Raphaelite repertoire of the late 19th century (see Evelyn De Morgan’s Cassandra reproduced above). On a literary level, Cassandra takes on an unprecedented importance in Christa Wolf’s Kassandra (1983); by using name and mask of the Trojan prophetess, the German writer and intellectual activates a new perspective and a new voice – both feminine and philosophical – on the Trojan War.

In Kaos, the character of Cassandra appears in the first episode of the series. Eurydice/Riddy is shopping among the supermarket stalls when she encounters a scruffy-looking woman (the actress is Billie Piper): dark regrowth at the base of her dishevelled, blondish hair; heavy make-up circling her eyes; smudged lipstick; a tattoo line, or perhaps a wound, straight down her nose; a dirty skin jacket thrown over faded clothes, worn haphazardly on top of each other. She is a tramp, a miserable, starving wretch (so Aeschylus in Ag. 1273-1274: ἀγύρτρια πτωχὸς τάλαινα λιμοθνής). Cassandra gives Riddy an intense, penetrating look and addresses her as if she has known her all her life. On her way out of the supermarket, Cassandra is stopped by a vigilante for stealing a tin of cat food, which she soon opens and devores ravenously; to Eurydice/Riddy, who has paid back the price of the tin, the tramp says: “Nobody believes a word I say, but it all comes true. I told them about the horse. I told them bout the men inside”. And later, addressing her directly: “Today’s the day […]. Today you will… Leave him: your love is dead”. Eurydice/Riddy senses the depth of the madwoman’s words and from there gathers a kind of encouragement to leave Orpheus (whom in this version of the myth she no longer loves). But the prophecy is, as always, ambiguous. In the same episode, Eurydice dies when she is run over by an ambulance (on the back of the vehicle – Covell warns us – only the freeze frame allows us to see a sticker with the image of a snake). The accident occurs because Riddy is distracted when he crosses paths again with the stunned tramp again in the middle of the road. Cassandra comments on the girl’s death with the words: “I told you you’d leave him. You leave everyone today”.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

P. Orlandini, s.v. Cassandra, in EAA II, Roma 1959, 401-404; O. Touchefeu, s.v. Ajas II, in LIMC I, Zürich und München 1981, 336-349; C. Wolf, Kassandra, Berlin 1983 (trad. it.: Cassandra e Premesse a Cassandra, Roma 1983).

mc

Ceneus

From left: Ceneus killed by a centaur, 5th century BC Attic vase, attributed to the Painter of Pan; British Museum, London; Johann Ulrich Krauss, Ceneus and Neptune, engraving for Book XII of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, before 1690; Ceneus (Misia Butler) in Kaos, Netflix 2024, Episode 2.

An armoured hoplite sinking into the ground under the blows of one or two centaurs armed with logs and stones: this is how Ceneo, the invincible hero who nevertheless perishes due to Zeus’ will, offended by his arrogance, is depicted in ancient iconography, on vases and friezes portraying episodes from the Centauromachia (the first mention of Ceneo as a lapithic hero is in Hom. Il. I, 264). The iconographic tradition thus seems to be silent on the event of Ceneus’ transformation from woman to man, which is instead present in numerous literary sources (the earliest description of the gender change is found in Acusilaus of Argos, FGrH2 F22, later taken up by Apollod. ep. I 22; Hyg. fab. XIV 4; Virg. Aen. VI 448-449; Ov. Met. XVII 171-209, 459-531). In this version of the myth, Cenis, the beautiful daughter of the Lapith king Aelatos, is transformed into an invincible warrior by Poseidon, who, after raping her, offers to grant her every wish. “This insult suggests to me a greater wish, that I may never again suffer such a thing; grant me that I may not remain a woman: you will have given me everything” (Ov. met. XII, 201-203). This, therefore, is what the Lapith wishes, and so, granted by the god, Cenis becomes the invulnerable hero Ceneus.

The story of Ceneus, in its two main variants (the divine punishment for his hybris and the change of sex), did not find a place in the literary repertoire of the following centuries, nor in the iconographic one, with the exception of some Renaissance and 17th century engravings for the 12th book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (see the one by Krauss reproduced above), where Ceneus, still a woman, is depicted in the courtship scene of the sea god.

In Kaos, the character (played by the transsexual actor Misia Butler) is introduced in the first scene of the second episode of the series: Ceneus, portrayed as a young man with a delicate face, slightly wavy dark hair and a hint of a beard, is working at the bar of a club when a group of women in military clothing appears and kills him by shooting an arrow into his chest. Among these warriors, Ceneo recognises his mother: in the series, the hero is the son of an Amazon, and therefore an Amazon himself, given a female name and gender identity at birth. Ceneus, who has always known that he wanted to identify with the male gender, has to hide his instincts because the Amazons expel all boys from their camp at the age of eleven, and so he has no choice but to continue pretending to be a woman until, at the age of fifteen, his mother, who has always known his true identity, gives him a new name and sends him away from the camp to protect and save him. But it is impossible to escape from the Amazons: the warriors find and kill him, considering first the deception and then the sex change as a serious challenge to their rigid and exclusive ethical and institutional model. In oppostion to a version of the ancient myth (cf. Virg. Aen. VI, 448-449), Ceneus does not take a female form but remains in the underworld, where he meets Riddy and plays a leading role in the challenge against the gods. Charlie Covell, interviewed for “Cosmopolitan” magazine about the approach to the story, explained the love for the myth of Ceneus and the idea to use it to create a trans protagonist in whom transsexuality was an integral part, without making it entirely define him; to do this, the producer transformed the violent warrior (“hyper-macho” as the original Caeneus is called in the interview) of the myth into “a much more gentle kind of almost reluctant hero warrior”.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

E. Laufer, s.v. Kaineus, in LIMC V, Zürich und München 1990, 884–891; M. Delcourt, La légende de Kaineus, “Revue de l’histoire des religions”, tome 144, n. 2, 1953, 129-150.

vsn

Medusa

From left: Head of a beam, frontal protome of Medusa from the first ship at Nemi, 25.8x23.5 cm, ca. 37-41 AD, Rome, Palazzo Massimo; Caravaggio, Shield with Head of Medusa, oil on canvas, 60x55 cm, 1598, Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi; Medusa (Uma Thurman) in Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief, Chris Columbus, 2010; Medusa (Debi Mazar) in Kaos, Netflix 2024, Episode 2.

In both archaic and classical iconography, there are frequent depictions of the face of the Gorgon. Along with Steno and Euryale, Medusa is one of the three daughters of Forcus and Ceno, and the only Gorgon who is not immortal, though she does have the power to petrify anyone who catches her eye. Her head, from which two wings protrude, is depicted frontally; sometimes her mouth is huge and wide open; her face is hideous. Between the 5th and 6th centuries, there is a tendency to humanise the face of the Gorgon, and Medusa begins to soften and acquire less disturbing feminine features. A more human aspect of the Gorgon is recorded in Roman art, where she appears at the centre of mosaics, on coins, in bronzes (an example is the beam head of the Nemi ship shown above) and, with Perseus, in various Pompeian frescoes. According to Ovid – the main mythographic source in the Roman sphere – Medusa’s terrifying appearance is associated with a punishment by Athena: after Perseus succeeds in beheading her by using the goddess’s mirrored shield to petrify herself, Athena, to punish the outrage, “changed the Gorgon’s hair into filthy snakes” (Met. IV, 799-801). In the most widespread iconographic scheme, Medusa’s face is inscribed in a roundel representing the goddess’s shield: the image so often reproduced in Greek and Roman art seems therefore to be interpreted not so much as a direct capture of the Gorgon’s face, but as a reproduction of her image reflected in Athena’s shield.

From the 16th century onwards, Medusa, and especially her head, reappeared as the subject of works inspired by the ancient myth: from the fresco in the Villa Farnesina, Perseus and Medusa (1510-1511), in which Baldassarre Peruzzi captures the moment when Perseus is about to cut off Medusa’s head, to Benvenuto Cellini’s sculpture of Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1554) from the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, in which you can see Perseus displaying the monster’s severed head as a trophy of his feat. The head of Medusa was particularly popular in the late Renaissance and Baroque periods: for example, Peter Paul Rubens’s Medusa (1617-1618) and, above all, Caravaggio’s masterpiece, The Shield with the Head of Medusa (1598), in which the face of the Gorgon – perhaps a self-portrait of the artist – is captured in an expression of horror as she realises her imminent petrification.

If the image of Medusa has focused on the detail of the severed head, anguicrinite head since ancient iconography, in some recent film versions Medusa also recovers a whole body, in the seductive forms of beautiful actresses. In the film Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief by Chris Columbus (2010), Medusa is played by the extraordinary Uma Thurman (see in Engramma, Alessandra Pedersoli’s contribution, Da Perseo a Perseo). The Medusa in the Kaos series, played by the actress Debi Mazar, also has the features of a strong, beautiful and self-confident woman, her eyes clear and magnetic, her hair anguiform. In the black-and-white world of Hades, sadly over-bureaucratised, she plays the role of manager and trainer of those souls who, having been buried without the Charon’s obol, have no chance of regenerating themselves by passing beyond the frame that promises a kind of metempsychosis and rebirth. Though trapped within the ranks of the regime, Medusa, intolerant of the totalitarian power of Hades and Persephone, flanks the resistance. As an accessory to her uniform – and perhaps even when she is in civilian clothes – she wears a turban on her head, pulled tightly over her head to prevent her serpentine hair from escaping and petrifying those who cross her gaze. If in Percy Jackson Medusa/Uma Thurman is still alive (up to and beyond the happy ending – unmissable! – inside the end credits), in Kaos she has already been killed by Perseus; she has been in the realm of Hades for a long time and is irritated and frustrated by the bureaucratic role she is forced into, partly because she has no way of exercising her deadly power: the souls of the dead cannot actually be petrified. And in a scene in Episode 2, when Ceneus, who has been transferred to a new office, bids Fotis, his three-headed dog, farewell for the last time, Prue’s soul, excited by her close encounter with the famous character, approaches her and asks: “Excuse me, ma’am – are you the Medusa?”; and Medusa, visibly annoyed, slips a snake that has slipped out from under her turban. Distraught and astonished, Prue touches her face and asks, “Why didn’t I turn to stone?” And Medusa, looking up impatiently, replies: “’Cause you’re fucking dead”.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

A. Giuliano, s.v. Gorgone, in EEA, III, Roma 1960, 982-985; I. Krauskopf, s.v. Gorgo, Gorgones, in LIMC IV Suppl. 1 2009, 230-232; O. Paoletti, Gorgones Romanae, in LIMC IV, Zürich und München 1981, 361-362; P.C. Bol, Argivische Schilde, OlympForsch 17 (1989), 45-47, in LIMC IV Suppl. 1 2009, 230-232; J. Hall, Dizionario dei soggetti e dei simboli nell’arte, trad. a cura di M. Archer, Milano 1983; J. Davidson Reid, C. Rohmann, The Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in the Arts, 1300-1990, New York-Oxford 1993; ICONOS s.v. Medusa.

ig

Prometheus

From left: Prometheus chained to the rock, Apulian goblet crater (detail), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Inv. No. 1969.9). 350-340 BC, possibly from Sybaris, attributed to the Painter of Branca; Piero di Cosimo, Stories of Prometheus, oil on canvas, 64x116 cm, c. 1515-1520, Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts; Prometheus (Stephen Dillane) in Kaos, Netflix 2024, Episode 1.

In Greek mythology, Prometheus – “the foresighted”, according to the etymology of his name as proposed in ancient sources – emerges as the central figure in several episodes that highlight his intelligence and ingenuity. In the central episode of his myth, after aligning himself with Zeus and the Olympians in their struggle against his Titan brothers, Prometheus is condemned to eternal torment for attempting to save humanity from the extinction that Zeus had already decreed for the flawed and inefficient human race. His act of rebellion is to gift mankind “fire and the arts”. The emphasis on this episode in mythical history is most notably found in Aeschylus’ tragedy Prometheus Bound (505-506), as well as in Plato’s Protagoras (320c-324a). In Aeschylus’ version, it is Prometheus’ love for mortals that motivates him to steal fire, an act for which Zeus condemns him to be chained in perpetuity “at the ends of the earth”, or, according to a variant likely introduced by Aeschylus, on a cliff in the Caucasus (for further discussion of this Aeschylean innovation, which later became predominant in mythography and iconography, see the article Prometeo alla colonna o alla rupe?). In Aeschylus’ tragedy (though also appearing earlier in Hesiod and archaic iconography), we find the image of the eagle – Zeus’ animal hypostasis – which devours Prometheus’ liver daily, only for it to regenerate each night (Hes., Th. 521-525; Aesch., Pr. 1021-1025).

The figure of Prometheus experiences no true period of oblivion in the transition from late antiquity to the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and eventually the modern era. Christian authors, such as Augustine (De civitate Dei, 18) and Lactantius (Narrationes fabularum Ovidianarum I, fab. 1), particularly engage with one aspect of the Titan myth – the portrayal of Prometheus as the Creator who fashions mankind from clay. This motif, already present in Ps.-Apollodorus (Bibliotheca 1.7.1) and Hyginus (Fabulae 142), likely contributed to Prometheus’ enduring presence in the figurative tradition of sarcophagi and in Late Antique culture. Tertullian, in his Apologeticus (18.2), endeavoured to Christianise this episode of the myth by interpreting Prometheus as a kind of pagan precursor to the Christian God of creation. In the 15th century, Prometheus resurfaced in the works of Marsilio Ficino, notably in his Opuscula theologica and his commentary on Plato’s Protagoras. The early 16th-century Epitoma super Prometheo et Epimetheo by Celio Calcagnini likely inspired Piero di Cosimo’s cycle of Storie di Prometeo paintings, one of the first Renaissance representations of the myth (see the essay and edition of Calcagnini’s text by Alessandra Sandrolini in Engramma). In 1510, the Titan – depicted with the eagle and chained to a rock – appeared in a woodcut included in a Venetian edition of Cicero’s Tusculanae Disputationes. In the 17th century, the theme was revived by artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, who depicted Prometheus naked, stretched out, and bound, while the eagle swooped down upon his body to devour his liver. Rubens combined two moments of the myth in his painting, adding the symbolism of the torch to the eagle’s torment, set within an abstract, suspended landscape where the Caucasus rock remains recognisably present.

In the Kaos series, Prometheus (Stephen Dillane) appears in the opening of the first episode, bound to a cliff in a barren landscape, wearing only red shorts, with an open wound on his side – the point where Zeus’s eagle rips out his liver. The Titan endures eternal torment: his liver regenerates nightly, thus perpetuating his suffering. Yet, he remains undaunted, optimistically anticipating his eventual liberation, foreseen through his prescience. Prometheus frequently intervenes, offering ironic commentary on the gods’ actions, speaking directly to the audience, thereby breaking the narrative fourth wall. In Kaos, Prometheus is not merely the victim of divine cruelty as traditionally depicted in myth; he serves as the series’ narrator, holding together the narrative threads. Each episode begins and ends with him. While he identifies as a “prisoner”, the poet Charlie Covell reimagines him as the confidant of Zeus (played by Jeff Goldblum), faithful to mythological tradition. Their bond is unexpectedly deep: despite Prometheus’ captivity, Zeus considers him his closest friend. However, the Kaos Prometheus, along with a group of gods and mortals, plots to overthrow Zeus and disrupt the cosmic order. In the final episode’s climactic scene, freed from his chains, Prometheus ascends Zeus’ throne in the Palace of Caserta, symbolising both his liberation and the apocalyptic overthrow of power, heralding a new era and a revolutionary reordering of the cosmos.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

J.R. Gisler, s.v. Prometheus, in LIMC VII, Zürich und München 1994, 531-553; ICONOS | s.v. Prometeo.

cc

*cc | concetta cataldo; mc | monica centanni; ig | ilaria grippa; vsn | viola sofia neri; ap | alessandra pedersoli; as | antonella sbrilli

English abstract

In Figurine dal mito, Charlie Covell’s Netflix series Kaos is analysed in its iconographical references: David Lachapelle’s promotional material – group posters and single shots of the cast – with its rather explicit nods to Baroque representation of mythological figures and scenes; the series’ settings as modern-day reinterpretations of the world of myth. Some characters – Cassandra; Caeneus; Medusa; Prometheus – are the focus of a more in-depth comparison with classical sources, in order to trace affinities and ruptures between the existing corpus of iconographic representations and the embodiment of ancient mythical figures in the updated narratives of contemporary actors and actresses.

keywords | Classical Tradition; Mythology; Iconography; Charlie Covell.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Redazione di Engramma (a cura di), Figurine dal mito. Kaos – a Netflix series (2024), “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 217, ottobre 2024, pp. 53-66 | PDF