A Tale of Two Misfits

The Sabbath/Shabbat across William Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress Series

Maurizia Paolucci

Abstract

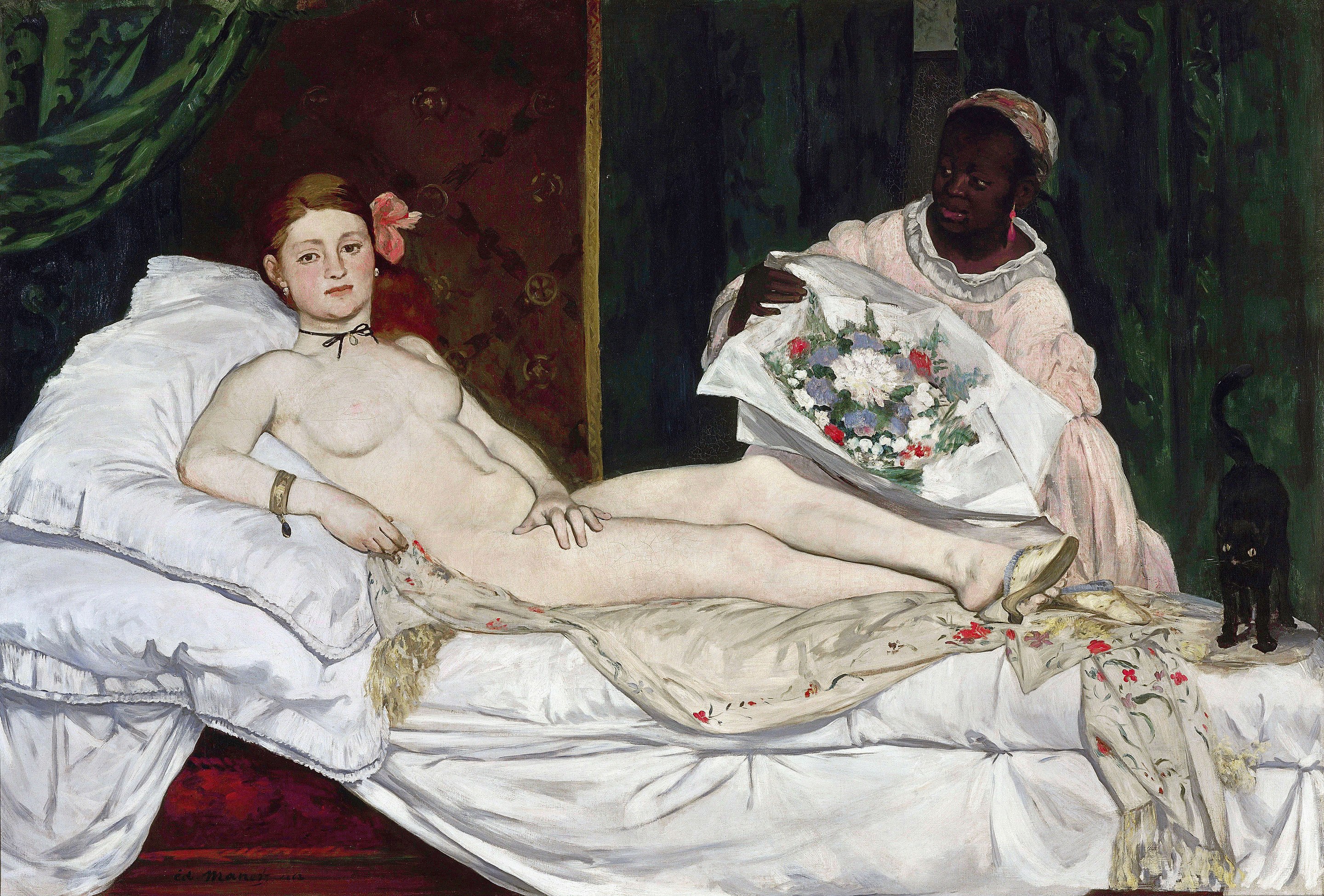

1 | É. Manet, Olympia, olio su tela (190 x 130,5 cm), 1863, Paris, Musée d’Orsay.

Back at the dawning of the digital age, in 1994, Finnish digital-art pioneer Marita Liulia had her multimedia work Maire published in CD-ROM format. She would achieve international fame two years later, with Ambitious Bitch, “a brilliant, visual update of western women and femininity, presented through self-irony and a funky sense of humour” through a CD-ROM whose structure offered “challenging visuality, rich audio presentation and an original navigating system” and as many as eleven “different destinations to dive into” (Bildmuseet 2002). Listing the destinations and their subtitles is the best way to introduce this paper; and a reminder that the word “bitch” went from only meaning a female dog to also being a derogatory term for women as early as the fifteenth century will not go amiss, either.

They are “Ambitious Blonde (The latest blonde jokes by herself); Erotic Tales (Dive into the secret world of female arousal); Female Perversions (Stunning stories by seven weird ladies); Sex or Gender (Do you really know who you are?); Ambitious Witch (See your past, present and future); Waves of Feminism (Modern, Post-modern and and Feminisms in a nut-shell); Body – Art of the Existence (This is my body, this is my software); Female Qualities? (Wise but vain? Illogical and emotional?); Trad. wit (Proverbs about women); Fashion & designers (Express yourself! Reinvent yourself!); Bubbles (Flea market for ideas on feminity)”, as it is reported in Bildmuseet 2002: the emphasis is mine and paves the way to discussing how the association between the ‘bitch’ woman and the ‘witch’ is to be find quite early in art history, the black cat in Édouard Manet’s Olympia being hardly the first instance of that.

In the third scene of William Hogarth’s series A Harlot’s Progress [Fig. 2], the cat is not black – which certaintly does not detract from the strength of the association, seeing as a pointy hat and a broom are hung on the wall. Both items already carried established witchcraft implications by the time Hogarth created the series; and, in this Georgian-Britain artwork, the broom is linked to the theme of prostitution as well, given the well-known period-typical appetite for sadomasochistic practices, such as flagellation, in brothels and similar dwellings. The hat I will talk about more extensively, but first of all I wish to draw the reader’s attention to my use of the term ‘scene’, a word unrevealing of the kind of object, and to explain why I used it.

2 | W. Hogarth, Plate 3 (“Apprehended by a Magistrate”) from the A Harlot’s Progress engraving set, etching and engraving, 1732. Original copperplate at the Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Edison Dick.

3 | Lorenzo Lotto, Annunciation, oil on canvas, 1534 ca., Villa Coloredo Mels Civic Museum, Recanati.

Hogarth had created the series as paintings in 1731, and gone on to making engravings of each image in 1732, as a limited edition, managing to have an Act of Parliament passed on 25 June 1735, the Engraving Copyright Act 1734 also known as the ‘Hogarth’s Act’, that prohibited the production and circulation of pirate copies which had soon started. In 1755 the six paintings were at Fonthill House, the country house of politician William Beckford, and were destroyed in a fire; but the six original copperplates survive, holdings today of the Art Institute of Chicago as a gift of Edison Dick, a Chicago industrialist who died in 1994 and in whose hands they had ultimately arrived after a wild ride of a provenance journey which included being sold in 1921 by legendary rare books dealer Bernard Quaritch and whose beginnings can be traced thanks to Ronald Paulson. Hogarth’s widow sold the plates in 1789 to engraver John Boydell, he in 1818 to publishers Baldwin, Cradock & Joy, and the firm in 1835 to publisher Henry Bohn – all of them producing legitimate copies (Paulson 1965, 71-72). From now on in the essay, I will refer to the scenes as plates.

In the first plate, “a beautiful young woman named Moll Hackabout […] arrives in London, fresh off the Yorkshire stagecoach”, looking, as per the scissors and pincushion hanging from her sleeve, for a job as a seamstress, “and is immediately lured into a life of prostitution” (Gallagher 2023, 70) by an old hag. The viewer who skips Plate 2 – that this paper will expand upon – and goes straight to Plate 3 can easily surmise that Moll has been successful enough in such a career, seeing as she is being tended to by a servant, but that she is going to endure her share of bad luck, judging by the bailiffs who, led by a magistrate suspiciously eyeing the broom and hat, are entering the room. The letter emerging from the half-opened drawer reads “To M. Hackabout”, whereas the trunk in Plate 1 did only sport evocative initials M. H.; now that the girl has come into her fate, she is revealed to have been surnamed by Hogarth after the notorious prostitute – and sister to just as notorious a criminal – Kate Hackabout, while her first name is commonly assumed to be Moll, either as a nod to character Moll Flanders in Daniel Defoe’s 1722 eponymous novel or, being a nickname for a Mary, in ironic reference to the Virgin (Paulson 2003, 28). In fact, the facial features of the hag luring Moll into prostitution in Plate 1 have been identified with brothel keeper Elizabeth Needham’s, and this encounter between a young Mary and an older Elizabeth is arranged so as to resemble the traditional Visitation iconography (Paulson 2003, 28). In Plate 4, Moll, having been arrested, is doing hard labour in Bridewell Prison. Beating hemp with an interestingly cross-shaped mallet, she is being derided and threatened with less-than-erotic caning, and all this reminds Paulson, this time, of the Mocking (and Flagellation) of Christ iconography (Paulson 2003, 28-45). My paper is indeed aimed at showing how Hogarth, the great satirist, was actually possessed of a compassionate attitude – his naming an innocent girl after the Virgin may have not come from a place of blasphemy. Paulson also deems Plate 3 to be structured along Annunciation lines (Paulson 2003, 28), which gets very interesting upon considering Lorenzo Lotto’s famous depiction of the Gospel episode: Lotto has not only included a cat in the scene, but also clearly hinted at the animal’s commonly accepted connection with witchcraft and devilry – it is scurrying away from God’s Archangel, in fear.

In Plate 5, Moll is back home, but dying of syphilis. Two famous doctors of the time are portrayed in the scene as they disagree over a possible cure; the black-wigged one on the left, Richard Rock, argues in favour of blood-letting his patient, while his colleague on the right, Huguenot refugee Jean “John” Misaubin, wants to give her his own (in)famous pills (Foster 1944, 357-58). Both methods would be useless, but then again, a mocking attitude towards doctors is easy to be found in Georgian-era art; Hogarth himself, back in 1726, had been among the artists satirising the episode of the successfully staged Mary Toft hoax. The woman had been believed to have given birth to rabbits, and Roland Paulson notes how Hogarth had drawn on Gospel imagery on that occasion as well: “[the positioning of the doctors at Toft’s bedside] resembles a traditional scene of Wise Men bearing gifts to the Christ Child; Mary Toft’s husband stands at the left, gaping at the miracle, in the position of Joseph” (Paulson 2003, 75-76). Though such an attitude was not specific to Georgian Britain (seventeenth-century Dutch painter Jan Steen’s Doctor’s visit scenes, for example, are built around gullible, self-assured physicians fussing over girls whose only ailment is the unfulfilled lust for their beaus: Mauritshuis 2011), it was all the stronger there due to the period-typical emphasis on rationality, an obsession that could “certainly not prevent doctors from believing the fraudulent tale” of a rabbit-birthing woman because of its own by-product, a “thirst for everything that was uncanny and bizarre” (Paolucci 2019, 107): “The very psychic and cultural transformations that led to the subsequent glorification of the period as an age of reason or enlightenment – the aggressively rationalist imperatives of the epoch – also produced, like a kind of toxic side effect, a new human experience of strangeness” (Castle 1995, 8). In this plate it is also shown that Moll has a child, a little boy. And, on the left wall, a cake is hung to serve as a flytrap – not any cake but, which this paper is going to show the significance of, a cake from the Jewish tradition, a Passover cake.

In Plate 6, Moll has died. A note reading “M. Hackabout died Sept 2 1731 aged 23” is placed on the coffin, whose lid is being used as if it were a countertop in some alehouse – drinks have been prepared and placed on it, and not all of the mourners are actually behaving as such: the girl on the left, for example, seems quite pleased by what the parson is discreetly doing to her with one hand as he suggestively spills the liquor he has in the other. The orphaned son of the dead bitch has put a hat on his head that may resemble, at first glance, his mother’s pointy hat, crumpled up on itself; the trimming marks it as a different one, regrettably for the iconologist who would otherwise be very much reminded of the “son of the witch” that Jules Michelet will describe a century later. And, speaking of hats, on the back wall the white ribboned one is hung that Moll was wearing in Plate 1, when she was a job-seeking seamstress; understanding what has happened to precipitate that innocent girl’s descent into her very dark fate necessitates going back to Plate 2 [Fig. 5], where she “is shown enjoying the relatively prosperous position of a kept mistress – but the household in which she works, and the trappings of the household, obliquely foreshadow her subsequent descent into disease and corruption, because the man who has taken her into keeping is a Jew” (Gallagher 2023, 70, emphasis mine). She has been – such is the message – into contact with the very embodiment of darkness and vice.

The Jews had been expelled from the Kingdom of England (“the United Kingdom” was yet to come) in 1290; they had been allowed to (openly) come back in the country in 1656, but the malice towards them was far from being over. It often took the form of an association between Judaism and witchcraft; the sorcerous connotation of the pointy hat has actually its roots in how the item does resemble the “Judenhat” (a cap that, from 1215 until the sixteenth century, the Jews in some part of the continent were forced to wear by papal decree, lest they be not immediately identifiable), as well as the hat worn by Quaker women, frowned-upon and held under witchcraft suspicions (the Quakers were a denominaton of Dissenters Christians; among other things, they did advocate for the safe return of the Jews in Britain). In 1775, artist Nathaniel Hone the Elder, wanting to make fun of colleague Joshua Reynolds in his satirical painting The Conjuror, depicted him as a warlock who magically creates his works from Old Masters’ prints, placing an owl near him, a pretty familiar – in the shape of paintress Angelica Kauffman, Reynolds’ rumoured lover – against his knees, and a Shield of David necklace around his neck (since Reynolds was not Jewish, the insertion of the pendant was arbitrary).

Oliver Cromwell’s 1656 Resettlement of the Jews had been an informal arrangement, overall accepted with good grace by the Britons due to a widespread belief that that was the first step towards having all the Jews in the country converted to Christianity, and, come the Stuart Restoration, King Charles II had not seen it fit to revoke the concession. But in 1753, George II’s royal assent was granted to an Act of Parliament – the Jewish Naturalisation Act – that would allow any Jew who so wished to simply apply to Parliament for citizenship after three years of living in Britain, with no requirement of them converting, and this triggered a strong reaction and fueled the custom afresh of satirising the Jews, more often viciously than good-naturedly. A “paper war” erupted, with a “bombardment” by means of satirical “pamphlets, prints and periodicals” going on for months, and the so-called Jew Bill was eventually repealed (Gallagher 2023, 79). Fake news, in particular, had been spread about a hidden agenda of having all the British men circumcised – which leads this paper back to the early 1730s and the Harlot’s Progress.

4 | Nathaniel Hone the Elder, The Conjuror, oil on canvas, 1775, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

5 | William Hogarth, Plate 2 (“Quarrels with her Jew Protector”) from the A Harlot’s Progress engraving set, etching and engraving, 1732. Original copperplate at the Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Edison Dick.

I have discussed how Moll is, across the series, Christian-connoted; in Plate 2, her protector is identifiable as a Jew not only through the “bushy black eyebrows and exaggerated nose” that “hundreds of other seventeenth-century […] anti-Jewish satires” (Gallagher 2023, 70) had agreed upon being code, but also through his surroundings and via the gesture performed by another character. The room “boasts two large paintings of Old Testament scenes”, namely Jonah undered the withered tree and the Ark of the Covenant entering Jerusalem, as well as “a fashionable black servant” (Gallagher 2023, 70) as an indicator of wealth and a pet monkey in reference “to the anti-Semitic trope of comparing aspirational Jews with monkeys attempting to ‘ape’ their Christian social superiors” (Gallagher 2023, referring to Gallagher 2019, 163). Another servant is in the room besides the black boy: a maid “hastily ushering another man out the door”, a younger man whose partial state of undress (including his sword being suggestively unsheathed) “confirms his identity as Moll’s lover” (Gallagher 2023, 70). As he sneaks out behind the Protector’s back, he is “unable to resist a final gesture of ridicule at his rival’s expense” and holds two fingers up: “his thumb and forefinger, as though indicating a length of two or three inches” (Gallagher 2023, 70), in the universal gesture proclaiming that a man has a poor excuse for a penis. If “persistent myths that Jewish men menstruated” (Gallagher 2023, 70) appealed to the period-typical British hunger for freakness and queerness (an example of which are, for example, the pregnant men featuring in the Cave of Spleen sequence of Alexander Pope’s 1712 Rape of the Lock, discussed in Paolucci 2019, 105-106), the “physiological anti-Semitism” (Gallagher 2023, 70) did also take the form of an obsession over circumcision.

British antisemitism of the time had a “bipolar nature” (Gilman 1986, 4), characterising Jewish men “as both sexually aggressive and sexually dysfunctional”, condemning them for their supposed lechery and at the same time ridiculing them as allegedly suffering from “a range of sexual disorders believed to make sex difficult, unsatisfying or impossible”, an attitude running “parallel to an equally paradoxical discourse around circumcision, a ritual that was understood as a prophylactic against, but also a potential cause of, various penile and sexual pathologies” (Gallagher 2023, 71). In fact, “the rite’s association with sexual or reproductive pathologies” was so strong that some practitioners, such as John Marten and John Bulwer, started “to classify circumcision as in itself a kind of disorder” (Gallagher 2023, 74). Made libidinous by their nature, circumcised as per their religion, Jewish men would find themselves “yearning for a sexual satisfaction” they could “never fully obtain” (Gallagher 2023, 75). In his 1707 work A Treatise of All the Degrees and Symptoms of the Venereal Disease, in Both Sexes, Marten “reiterated the myth – attributed to John Browne’s 1646 treatise Pseudodoxia Epidemica – that […] uncircumcised men were better at maintaining an erection, and therefore, at giving and receiving sexual pleasure” and were, as a result, quite sighed after by the unsatisfied Jewish women (Gallagher 2023, 74). Sex manuals such as Nicholas Venette’s 1702 Tableau de l’amour Conjugal, Pierre Dionis’s 1719 General Treatise of Midwifery, Faithfully Translated from the French, and Pseudo-Aristotle’s 1684 Aristotle’s Master-Piece “identified the prepuce as central to sexual satisfacton for both male and female partners”, due possibly to the glands of the uncircumcised retaining more sensitivity, possibly to the movement itself of the foreskin (Gallagher 2023, 72-73, also citing Darby 2004, 22-43). As full of greed by nature as they were of lust, Jewish men would then find consolation in flaunting their wealth by keeping mistresses, despite not being able to properly enjoy them: “[Eighteenth-century British] representations of Jewish sexuality [are] essentially representations of Jewish finance”, where lasciviousness is a “stand-in” for avarice and “sexual predation a metaphor for bullishness in the marketplace” (Gallagher 2023, 75), both in art and in literature – with regard to the latter, Laura Rosenthal points out that Jews and prostitute are often aligned, due to them both representing “the unbounded drive toward accumulation” (Rosenthal 2015, 72), which is what happens in the series as well: greedy Moll needs a Jew protector to grant her a comfortable lifestyle, plus a wholesome Christian lover to give her pleasure. A six-canto dramatisation of the series does feature character “Betty” (or “Bess”) thus egging her on to cheating:

Besides, he is no Christian – then

He’s not all o’er like other Men;

Jews clip, and pare – Dogs! they diminish

The Instrument that Man does finish

(Unknown Author 1732, quoted in Gallagher 2023, 76, emphasis in original).

Just like, in Britain, “anti-Jewish discourse throughout the early modern period” had “accused Jews of lustfulness, effeminacy and sexual deviance” (Gallagher 2023, 70), nineteenth-century Venetian poet Pietro Buratti would lash out at Jewish women specifically, hatefully branding them as lesbians. At the time of his writing that, the Jews being equal to any other citizen still felt shockingly new and subversive, seeing as it was something as recent as 1797, following the fall of La Serenissima Repubblica and Napoleon’s decree that the Jewish segregation come to an end. Buratti’s verses – the translation into archaic English on here is mine – present his readers with belief-begging sceneries:

La vulva più fetida

De l’empio israelo

Con arte diabolica

Fa guera a l’oselo?

(Buratti [1823] 2017a)

[How now! The most stinking Fannies

from impious Israel

are waging War on Cock

with a devilish Craft!]

And pose to them rhetorical questions:

Se pol dar magior strapazzo

Per el sesso mascolin

Che se intimi bando al cazzo

Da una fia de Beniamin?

(Buratti [1823] 2017b)

[What can be more distressing

to a Man

than Cock being scorned

by a Jewish Woman?]

Also, this supposed romantic rival of his he calls a “striga” (Buratti [1823] 2017b), a witch. He is describing a lesbian who is also a witch who is also a Jew: a most hideous villaine – just like a woman who is a witch and a prostitute.

6 | William Hogarth, Plate 5 (“Expires while the Doctors are Disputing”) from the A Harlot’s Progress engraving set, etching and engraving, 1732. Original copperplate at the Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Edison Dick.

7 | An all-in-one view of the Harlot series. Top: left to right 1-2-3. Bottom: left to right 4-5-6.

8 | Left to right: Installation view of Mat Collishaw’s Shooting Stars at Haunch of Venison in London, 2008;

Caravaggio, Pilgrim’s Madonna (or Madonna di Loreto), oil on canvas, 1604-1606, the Cavalletti Chapel in the church of Sant’Agostino, Rome;

Mat Collishaw, Gary Gilmore, from the Last Meal on Death Row series, C-type print, 2012.

Moll’s story is a tale of two misfits indeed, and the Jewish character, though moneyed and privileged, cannot possibly ignore that, in British society, he is one. The Passover-cake-turned-flytrap in Plate 5 [Fig. 6] has been probably sent to Moll by him, for her to feed herself and her child on, as a gesture from one outcast to another, in merciful forgetfulness of her having, at a certain point, probably due to his finding out about the cheating, ceased being on his good side (in Plate 3 she is no longer in the lavish lodgings where she was kept). But Moll manages to symbolically have the upper hand, dispatching the cake to serve as the tool for a gross task.

Previously-mentioned Paolucci 2019 also discusses how 1966-born artist Mat Collishaw dealt with the theme of prostitution in the 2008 installation Shooting Stars, where “a series of haunting images of Victorian child prostitutes are projected in rapid succession onto walls coated with phosphorescent paint. The ghost of these pictures is burnt onto the walls and gradually fades over time. Occasionally a projector will drag the image across the wall before leaving it burning bright at the end of a trail of light. This has a similar effect to the arc of a shooting star. The lives of these girls sadly often resembled their presentation here” (Collishaw 2008). This expressive use of light is to be considered in relation to Collishaw’s openly being inspired by Caravaggio, the master of light whose art in turn did borrow from the underworld, from the margins of society (for example, the Madonna di Loreto and the Madonna dei Palafrenieri are said to have the face of prostitute Maddalena “Lena” Antognetti, and their Christ Children to have Lena’s son’s). And it is remarkable how Collishaw, providing a photographic record in 2012 of the last meals of some men on American death row, would arrange and light up the foods and tableware as if that were a Caravaggio still life. Hogarth did not so much take a stand for the hard done-by as scatter his satire across many different social groups, like an English, eighteenth-century, brush-wielding Tom Wolfe. But it was possibly in his sparing no one his lampoon that his empathy lay; possibly he was (though he had not been alone in appealing to Parliament for the Act that would protect an engraver’s rights) a favourite target for unlawful reproduction exactly because of his work’s potential for resonating with anyone – also when it came to fueling specific ideologies. The antisemites of the time must have completely overlooked the Protector’s humanity in the Harlot series, falling instead upon the chance to use the prints as if they were propaganda pamphlets.

Having painted A Rake’s Progress series in 1732-34 and made engravings of it in 1734, Hogarth made sure he waited until the Act had properly passed in 1735 before he had the prints published; and as Liam Kelly reports, he had to go to even greater lengths. “X-rays and infrared scans of […] A Rake’s Progress show that he changed some of the eight paintings in the series after completion”, when “knock-off prints started appearing” which had been possible because, as Hogarth denounced via the London Evening Post, “mean and necessitous Persons” (as he himself called them) on scheming printsellers’ payrolls had managed to go see the paintings at the artist’s home and successfully memorise key details, subsequently “having copies engraved and printed before Hogarth could do so” (Kelly 2021). The Engraving Copyright Act was to be repealed by the specific sections of, and schedule to, the Copyright Act 1911, and meant to replace, consolidating them, the various Copyright Acts that, starting 1734, had been passed throughout the course of British history. It is interesting how things come full circle in an essay that I have started off as well as wrapped up by mentioning digital art, that, copyright-wise, poses any sort of new challenges, as this “Engramma” issue is aimed to show.

Bibliographical References

- Bildmuseet

Marita Liulia, Ambitious Bitch [site card], last access 26 March 2025. - Buratti [1823] 2017a

P. Buratti, Tribade seconda ossia il Cazzo d’Ancillo, in Poesie e satire di Pietro Buratti veneziano, Amsterdam 1823. - Buratti [1823] 2017b

P. Buratti, Tribade prima, in Poesie e satire di Pietro Buratti veneziano, Amsterdam 1823. - Castle 1995

T. Castle, The Female Thermometer. Eighteenth-Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny, New York 1995. - Colishaw

Mat Colishaw, Shooting Stars [site card], last access 26 March 2025. - Darby 2005

R. Darby, A Surgical Temptation. The Demonization of the Foreskin and the Rise of Circumcision in Britain, Chicago 2005. - Foster 1944

F. Foster, William Hogarth and the Doctors, “Bulletin of the Medical Library Association” 32, 3 (July 1944), 356-368. - Gallagher 2019

N. Gallagher, Itch, Clap, Pox. Venereal Disease in the Eighteenth-Century Imagination, New Haven 2019. - Gallagher 2023

N. Gallagher, The Jew’s penis. Circumcision and sexual pathology in eighteenth-century England, “Medical Humanities” 49, 1 (March 2023), 70-82. - Gilman 1986

S. Gilman, Jewish Self-Hatred. Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews, Baltimore 1986. - Kelly 2021

L. Kelly, Hogarth overpainted canvases to stop the fakes’ progress, “The Sunday Times”, 31.10.2021. - Mauritshuis Museum

Jan Steen, The Doctor's Visit [site card], last access 26 March 2025. - Paolucci 2019

M. Paolucci, Queering the Body, Birthing the Nation, Gendering God. An Atlas, “La Rivista di Engramma” 168 (settembre-ottobre 2019), 99-111. - Paulson 1965

R. Paulson, Hogarth’s Graphic Works, New Haven 1965. - Paulson 2003

R. Paulson, Hogarth’s Harlot. Sacred Parody in Enlightenment England, Baltimore 2003. - Rosenthal 2015

L. Rosenthal, Infamous Commerce. Prostitution in Eighteenth-Century British Literature and Commerce, Ithaca 2015. - Unknown Author 1732

The Harlot’s Progress; Or, the Humours of Drury-Lane, London 1732

Abstract

The year is 1732, and no sooner has William Hogarth made engravings of the six paintings forming his Harlot’s Progress series than the production and circulation of pirate copies has started, prompting him to lobby Parliament together with some colleagues who face the same issue, appealing for an Act to protect their rights as creators, which is eventually granted them. Working off of that episode, the paper does extensively discuss the series of engravings and delves into what may have possibly made Hogarth’s work so palatable to pirates: and amazingly enough, this occasions mentioning a work of digital art and thus casting a bridge into a time – the present day – where piracy is, as other essays in this Engramma issue do discuss, all the more widespread.

keywords | William Hogarth; A Harlot’s Progress; Digital art; Piracy; Eighteenth century; Engraving Copyright Act 1734.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Maurizia Paolucci, A Tale of Two Misfits.The Sabbath/Shabbat across William Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress Series, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 222, marzo 2025, 105-116 | PDF