Elfriede Jelinek's Bambiland (2003), Yana Zarifi's Persians (2006) and Zack Snyder's 300 (2007), three different ways to invent ourselves

Freddy Decreus

English abstract

1. Locating the question

Aischylos’ Persians (472 BC) was one of the first accounts of the way the ‘West’ started to face the ‘East’. This tragedy has been important for a great variety of artistic, political and ideological reasons and its reception during a period of 2500 years focused upon the defence of Western freedom and the heroic efforts it sometimes takes to face an unbeatable enemy. It was one of the first documents that emphasized the idea of fighting for freedom against all odds and so it opened debates on power, freedom and politics in the ancient Greek (especially Athenian and Spartan) world (Loraux 1986). Right after the Persian wars, its content was understood in terms of an elaborate network that served to characterize ‘the barbarian’ (see the many Amazonomachies, Centauromachies and Gigantomachies) and for this purpose old mythology was relieved by newer versions, pointing into new ideological directions. In her fascinating book Inventing the Barbarian. Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy (1991), Edith Hall showed how the increased interest in the barbarian had to be seen as a very conscious manoeuvre of tragic poets to foster a new nationalistic ideology. The poets, she said, “created a whole new 'discourse of barbarism', as a component of this ideology, a complex system of signifiers denoting the ethnically, psychologically, and politically 'other' [...] Many of these were to be of lasting influence on Western views of foreign cultures, especially the portrait of Asiatic peoples as effeminate, despotic, and cruel” (Hall 1991, 2).

Analyses of this kind were an interesting test-case to introduce a Western public into discussions about a great ideological divide and a 'clash of civilizations' (Huntington 1996). They continuously appealed for oppositions between a generalized 'us' and 'them' (Hornblower 2001), between the enlightened Western citizen and the racial and geographical other, or in psycho-analytical terms between all kinds of ego's and repressed 'strangers in ourselves' (Kristeva 1988). They helped to articulate identities in both the French Revolution and the Greek War of Independence and both Iranians and Greeks conceived their actual political positions through it (Bridges, Hall, Rhodes 2007). Moreover, since the Persian attack can be seen as one of the first major expeditions organised by the East against the West and since conversely the West, with Christianity ahead and Georges Bush in its wake, did not yield in planning dozens others, the Persian Wars never stopped to play a part on the agenda of international politics and religion. Even during the Cold War that opposed the United States to the Soviet Union, the opposition East vs. West served propaganda ends, as was illustrated by The 300 Spartans, directed by Rudolph Maté in 1962 (Levene 2007).

From a philosophical point of view, it lasted till 1978 and the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism. Western Conceptions of the Orient before the Western intellectual world stopped indulging in fancies about the Eastern Other. As Said mentioned in his Introduction: “The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences”. But ever since the terrible civil war of 1975-76 in Beirut, this Oriental vision "was disappearing; in a sense it had happened, its time was over", and much worse "it seemed irrelevant that Orientals themselves had something at stake in the process, that even in the time of Chateaubriand and Nerval Orientals had lived there, and that now it was they who were suffering" (Said 1995, 1). From then on, Orientalism became a "Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient", a construction and a discourse, like Foucault described them in L’Archéologie du savoir (1969) and in Surveiller et punir (1975), an authoritative position by which European culture was able “to manage – and even to produce – the Orient politically, sociologically, militarily, ideologically, scientifically and imaginatively during the post-Enlightenment period” (Said 1995, 3).

Probably to the surprise of most classicists Said also focused on the ideological impact of two Greek tragedies: “two of the most profoundly influential qualities associated with the East” appear in Aischylos’ The Persians, the earliest Athenian play extant, and in The Bacchae of Euripides, the very last one extant. Aeschylus portrays the sense of disaster overcoming the Persians when they learn that their armies, led by King Xerxes, have been destroyed by the Greeks. The chorus sings the following ode, developing Hecataeus’ radical idea of dividing the world in two major continents, Europe and Asia (cf. his Periegesis):

Now all Asia's land

Moans in emptiness.

Xerxes led forth, oh oh!

Xerxes destroyed, woe woe!

Xerxes' plans have all miscarried

In ships of the sea.

Why did Darius then

Bring no harm to his men,

When he led them into battle,

That beloved leader of men from Susa? (vs. 548-558)

What matters here, he said, is that “Asia speaks through and by virtue of the European imagination, which is depicted as victorious over Asia, that hostile 'other' world beyond the seas. To Asia are given the feelings of emptiness, loss, and disaster that seem thereafter to reward Oriental challenges to the West; and also, the lament that in some glorious past Asia fared better, was itself victorious over Europe” (Said 1995, 55-56). In his opinion, these very lines conceived by Aischylos in the wake of the Persian Wars, or, to be more precisely, written down during a century that Athens could not escape Persian threats, were very fundamental ones, if only for ideological reasons. Indeed, “the two aspects of the Orient that set it off from the West in this pair of plays will remain essential motifs of European imaginative geography. A line is drawn between two continents. Europe is powerful and articulate; Asia is defeated and distant […] Secondly, there is a motif of the Orient as insinuating danger. Rationality is undermined by Eastern excesses, those mysteriously attractive opposites to what seem to be normal values”. In the eyes of Said, the Persians of Aischylos is one of the oldest Western statements of an ontological and epistemological divide and hence of a “Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient” (Said 1995, 57).

It was only at the end of the twentieth century that postcolonialism, as an internationally recognized scientific methodology, opened Western eyes and indicated that the intrinsically rich and high civilisation that was ancient Persia had been taken hostage by a largely hostile press which was embedded in the European tradition, but which ultimately originated in antiquity (Burn 1988; Brosius 2006; Bridges, Hall & Rhodes 2007). Differences in the gaze that shaped both parties can reside in very small details, as the ones used for instance by Steven Pressfield in his novel Gates of Fire (1998), a bestseller in both the USA and the UK, a book that apparently caught the attention of the great public, as it was retelling the story of the battle of Thermopylae. In her analysis of the success of this novel, Emma Bridges mentions, as a small fait d’hiver, the following reaction of a former captain of the US Marine Corps who has seen service in Iraq and Afghanistan and who wrote an article in the “Washington Post” (July 15, 2005). Captain Nathaniel Fick specified: “If there’s a better description of combat leadership, I’ve not seen it. I recognized Pressfield’s characters in the men I was serving with; weapons and tactics evolve, but the people stay the same”. So too, Bridges suspected, “does the horror, discomfort, and camaraderie of face-to-face combat. Fick insisted that every member of his own platoon read the novel”. Certainly this novel recognized universal problems and reactions in the face of ultimate situations, but there was more. In Gates of Fire, a minor and invented character survived the battle and was taken to the Persian court for questioning by Xerxes’ advisers, a rather traditional thematic excursion, but important because it allowed a narrative voice to report from both sides of the conflict. Giving the opportunity, even only occasionally, to the Persians to formulate their version of the story, reminded us, Bridges says in her last note, of “what countless postcolonial novelists have been doing for other peoples under later empires” (Bridges 2007, 419, n. 26) and she explicitly mentioned one of the first and still important readers on that topic, The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures, by Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin (1989). Since the war against Persians so often has been seen as one of the first (Western) Crusades (see Karen Armstrong, Holy War: The Crusades and their Impact on Today’s World, 1988), one easily understands why it was so important that, in a radically changed intellectual climate that has been promoted by media all over the world, the story of the Crusades also was told and recorded from ‘the other side’, as Amin Maalouf did in his pioneering The Crusades through Arab Eyes (1984), collecting testimonies from contemporary Arab historians and chroniclers.

2. Three important recent interpretations: Elfriede Jelinek's Bambiland (2003), Yana Zarifi's Persians (2006) and Zack Snyder's 300 (2007)

2.1. Elfriede Jelinek, Bambiland (2003)

The first example of contemporary reception to be discussed here is a play written by the Austrian novelist, dramatist and essayist Elfriede Jelinek, one of the most radical authors Europe knows today, Austria’s cultural “pain in the ass”, “best-hated author” and “the world’s greatest agitator”, but nevertheless recipient of the 2004 Nobel Prize (as the jury said “for her musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays that with extraordinary linguistic zeal reveal the absurdity of society's clichés and their subjugating power”). Officially, Bambiland is called a play (published together with Babel in 2005 as “zwei Theatertexte”), but its seventy pages (German version, 2004, 15-84) long outburst of criticism and aggression is as unplayable as most of her other work. Writing in the line of her Austrian predecessors Robert Musil, Thomas Bernhard and Ingeborg Bachmann (although violently refusing any characteristic that could label and identify her as ‘Austrian’), her style is polemic, critical, often ironic, sometimes feminist.

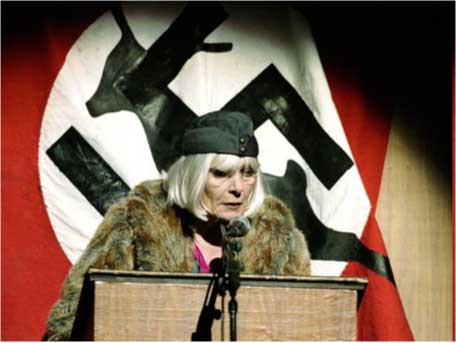

Bambiland, Wiener Burgtheater. Picture by Gabriele Engelhardt (2003), Künstlerische Mitarbeit. Christoph Schlingensief

The two plays, Bambiland and Babel, were written in the wake of the invasion and occupation of Iraq and dealt with the way media coverage handled this provocation. Both plays were born out of indignation raised by the photographs taken in the Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib prisons and severely criticized blind patriotism that too easily relies upon over-simplified messages. In Bambiland, entertainment industry created a new kind of Disneyland and world-wide amusement park, using media and internet's availability all over the world, called 'Wartainment'. Everybody is welcome to play and participate, and whether you like it or not, you are involved, since you never escape the type of media coverage that occurred during the last war. An extended monologue with shifting voices and a multi-layered language, staging Dick Cheney and the Halliburton “high-priced corporate conglomerate” always “at your service”, Jesus, Christian crusaders, policy advisers, high-tech weapons experts, ..., they all constitute an incalculable plethora of economic and political interests that tries to expunge all doubts and dissent from a Western conscience. Apparently, a wide-ranging first person 'I', sometimes swelling into a more collective 'we', changing and skipping within a phrase or even a single word, is deeply worried about the worldwide privatization of media and weapons production that gives way to 'infotainment', an attitude that reduces every bit of historical seriousness and turns a public into passive consumers.

Bambiland. Picture by Christian Brachwitz

Aischylos' tragedy already staged an ‘embedded reporter’ and Jelinek continues this double voyeuristic perspective, the camera perspective of those on the frontline and of those who observe the observers, that means 'we'. On the one hand, Western observers congratulate themselves for the balanced nature of their coverage, because, after all, they are Westerners, always occupied with the 'truth' and having an open eye for the situation of the losers. On the other, Western TV allows all of us to sit in comfort and to enjoy the process of the coverage itself, long live CNN that stages all of this for us. This attitude radically asks the question of our own involvement, or as Katrin Sieg puts in her analysis of the way modern politics is choreographing the global: “The continuities she [sc. Jelinek] charts between ancient Greek tragedy and contemporary 'wartainment' underscore not merely the implication of European democracy in imperialist projects but identify the ambivalence of empathizing with and eradicating the Other as constitutive of democratic art” (Sieg 2008, 144). "This crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take a while", one of the many catchy phrases that president Bush in 2001 thought of, and later on completely dropped from his vocabulary (see: The big scary list of George W. Bush Quotations), belongs to a more generalized attitude that can be labelled ‘European universalism’. Katrin Sieg connects this overall pattern to what she is calling “the synchronization of natural, divine, and political order underpinning the historic victory of Greek democracy in The Persians and [that] might be regarded as the first manifestation of such a ‘European universalism’ (to quote Wallerstein, 2006)”, one that “framed historic projects of imperial domination as the generous impulse to bring Christianity to the heathens, Western civilization to the colonies, modernity to the third world, and democracy and human rights to rogue states, that is, as the disinterested sharing of universal values” (Sieg 2008, 150).

Bambiland. Picture by Karin Rocholl

Warlords led by a 'Jesus W. Bush' team, drunk with victory, do not doubt their divine position, since their God 'is in the right'. This “God is a born-again Christian, and he can be born and reborn again and again... And what's even better is that he can also employ the logic of the most unbelievable non-believers and the morality of the most unbelievable non-believers”. Sometimes this hilariously twaddling voice really doubts that he is God, but then again, there is his father who persuades him of his divine mission: “Sometimes I have my doubts, but my father just handed me a note stating that I, too, am God. He's not the only one. In any case, no sooner had I been informed of the fact that I am God, of course I immediately set out to serve some purpose, in the sense of Darwinian biology, which is to say to assert my fitness in the struggle against others. Who could be more fit than someone who is at once God and man? People should all become like me, but they cannot”. Major tools to acquire this divine status are a large series of heavy weapons and missiles, the BGU-28 bombs (“5000-plus pound bunker buster, 4600 pound launch weight with 630 pounds of high explosives...”), cluster bombs, graphite bombs, ..., items that are to be bought in large quantities, because “one is hardly enough. Take several, take several of them off our hands! If you've already got fighter aircraft, it's best that you take a couple thousand of 'em off our hands, then we can really give you a discount. Promise”.

In a hallucinatory finale, war industry, religion and patriarchal power come together, only to illustrate that the supposed liberation of Iraq is no more than a large scale farce and a brutal rape. Images of exploding missiles “penetrating hardened Iraqi command centers located deep underground” have a definite sexual flavour. The narrative voice, godlike and bellicose, developer of the very sophisticated BGU-28 missile (“length: 18 feet; diameter: 1.2 feet”), the one that is guided by laser pointers and penetrates into the earth as deeply as 30 meters, is giving a blowjob before launching, and, unbelievable but true, “you've never had your mouth on anything that hard, folks”.

In December 2003, Jelinek's text was staged on the experimental stage, the Akademietheater, of the Vienna Burgtheater by the performance artist, theatre director and filmmaker Christoph Schlingensief, one of Germany's most engaged political enfants terribles (who died on August 2010, hardly forty nine years old).As Jelinek herself described it, Schlingensief rendered her “own amalgam of media reports about Iraq in a way that amalgamised it once more with his overwhelming visual level” (Lücke 2004, 230). A nearly excessive multimedia presentation used a number of multiple video projections in order to create a generalized climate of uncertainty and insecurity. This intermedial polyphony heavily focused on the voyeuristic pleasure of seeing the other suffer and die, a spectacle that explicitly had pornographic intentions and was meant to radically disturb theatre as representation of reality (Koerner 2010, 153-168).

2.2. Yana Zarifi, The Persians (2006)

While Jelinek and Schlingensief stand for a posthumanist disbelief of the artist in world politics and current media coverage, a point of view that led them to subvert language and theatre and to evoke intolerable physical violence on human bodies, Yana Zarifi's staging of The Persians dealt with a completely different project, one that returned to the inner, often spiritual, life of actor and audience. As artistic director and co-founder of the international London-based theatre company Thiasos, she explored eastern theatrical techniques, especially dances that would allow a better understanding of the ritual character of Greek tragedy, especially of the function of the chorus. Expeditions took her to Bali and Lombok in Indonesia (1994) and Kerala in India (1996), where she studied the functioning of a dancing and singing chorus in ceremonial contexts. Currently, she is an Honorary Associate of Royal Holloway University of London and recently she received a Getty Scholar Award for the 2006-7 year to continue her research into Persian (Islamic and pre-Islamic) performance traditions in relation to theatre.

Thiasos was founded in 1997 “by a group of academics and theatre professionals” whose mission it was “to put music, dance, colour and spectacle back at the centre of Greek tragedy and comedy – where it always was”, an artistic programme that was directed against a certain kind of naturalism that had de-sanctified many performances of Greek tragedy all over the world. Central to the proposals Thiasos published on their website (www.thiasos.co.uk) was “a vision of tragedy as a spectacular ritual performance, combining a highly wrought, and often densely poetic text, with vivid and emotive dance and song – a kind of ancient Gesamtkunstwerk. The formal organisation of the spoken text, the elaborately stylized costumes, and the consistent musical framing, together imply a highly ‘coded’ acting technique whereby the emotional content is communicated in a systematic language of gestures and symbols”.

Before staging The Persians in 2006, the company already performed three plays by Euripides (Medea, 1997; Hippolytos, 1998-2004; Bacchae, 2003) and two by Aristophanes (Wealth, 1999-2000; Peace, 2001). Medea was a complete play in the original Greek with dancing drawing on South Indian Classical Style, Hippolytos was adapted as a drama in Indonesian style, one that relied heavily on Balinese mask carving and its tendency for archetypal expression (fresh-coloured masks for the mortals, white and refined ones for the gods), and Bacchae used a lot of sounds from Greek and Turkish musical traditions. Wealth was conceived through puppetry coming from Karaghiozi, a form of shadow puppet theatre that arrived in Greece from Turkey in the 19th century and also used masks derived from the comic 'painted faces' characters of popular Chinese opera. The other comedy, Peace, drew on ancient Greek rituals of anabasis – the emergence of rural deities from the earth – and on modern Greek music to celebrate a world of agriculture displaced by war and by the commodification of the planet.

Preparing the staging of Persians, Yana Zarifi did some research in Central Asian cries and songs and especially into the falak songs of Tajikistan, because she was attracted by the array of metrical and extra-metrical 'cries' in Persia. To render all the cries and sounds present in the tragedy, the Persian falak seemed so much indicated because it was associated with processes of pain and healing. One of the simple questions that was present during the start-up of Persians was this one: what did all these ototototoi and papai really sound like, Zarifi wondered, when heard from that other side, the Persian side, where we always remain complete outsiders? Contrary to many contemporary theatre groups that paid a visit to Salamis in order to feel and experience the memories of the (Greek) past (as Lydia Koniordou did with the 'National Theatre of Greece' preparing her Persians, 2006), she travelled to Tajikistan, a country situated in the area of the legendary Silk Road between Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and China, and listened to these remnants of old Persian melodies of grief and pain.

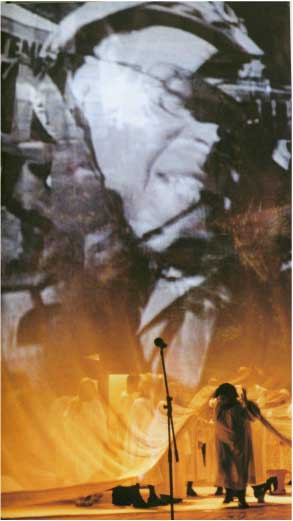

The Chorus in Thiasos' Persians: New College, Oxford (2006). Picture by Nina Ayres (left); Cyprus (2006). Picture by Yana Sistovari (right)

Since the success of this whole production heavily relied upon the amazing voice and presence of Rustam Duloev, leader of the chorus, the primary focus has to be laid on this remarkable way of singing. Duloev was born in Tajikistan and reared in the specialized falak tradition which he combines with a celebrated operatic career in Italy. Falak is a genre of lament that in a musical, poetic and spiritual way intimately expresses local beliefs of Eastern Tajikistan. Among the many types of falak which are performed in various circumstances, specifically one proved to be important for the staging of Persians, since it dealt with the process of musical healing by modulating stress and depression. Some of them might have been known to a larger public in the West, since in recent ritual performances in the United States by the renowned Turkish 'Whirling Dervishes of Rumi', Turkish, Arabic and Persian languages were used to vocally express an impassioned love for God. During these performances which lasted for almost three hours, moments of extreme poignancy generally used ancient Persian as the language of choice for spiritual communion and praise. The falak that was chosen for Persians was the expression of a 'religious' experience, not only in terms of its potential spiritual nature, but also in the way it connected as a religio (re-ligare) and (re)diffused electrical discharges from the brain all over the human body. Most of the reflections presented here on falak can be explored in a more profound way in Benjamin Koen's books and articles on musical healing and music therapy in non-Western areas, see his Musical Healing in Eastern Tajikistan: Transforming Stress and Depression through Falak Performance (2006) and Beyond the Roof of the World: Music, Prayer, and Healing in the Pamir Mountains (2008). The specific music for the production was composed by the renowned Tolib Shakhidi, former pupil of Katchaturian and composer of numerous symphonies, ballets and operas of worldwide acclaim. For the sung parts, Persian, English and occasional Greek phrases were used.

Thiasos' Persians: New College, Oxford (2006). Picture by Nina Ayres

On top of this deep-going musical setting that left nobody untouched and indifferent, the production staged sumptuous Uzbek costumes made from materials acquired in Bukhara and Samarkand and designed by Nina Ayres. All through the production, Dareios' royal costume remained visible at the centre of the stage. His ghost wore it to 'materialise' and Xerxes was dressed in the same royal robe by his mother in order to regain potency. Three times, the long list of lost Persian commanders was repeated, a striking triptych that in pure mantra style could not get even with death and massacre.

Thiasos' Persians: New College, Oxford (2006). Picture by Nina Ayres. Rustam Duloev

Transforming pain through healing music, (re)wearing ancestral clothes, and repeating three times the loss of compatriots, the performance heavily relied upon on the social-emotional and ritual aspects of what is meant to be human and to be deprived of our social and psychological centre. It asked our attention for the extraordinary energy that healing music from an unknown culture could evoke in the minds and hearts of a Western audience.

2.3. Zack Snyder's (and Frank Miller's) 300 (2007)

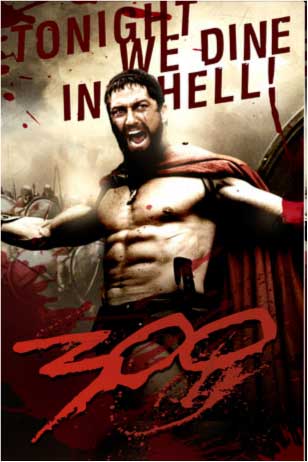

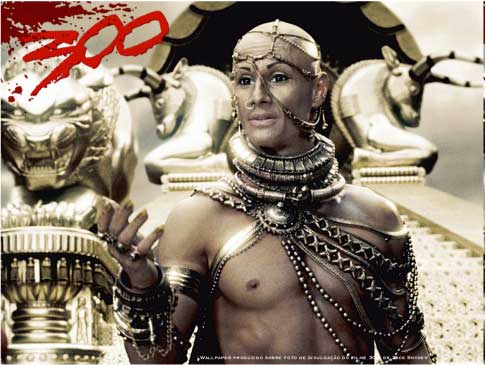

For those who do not understand why Jelinek created such profoundly post-humanist rewritings or do not see as George W. Bush “why do they hate us?”, it is indicated to watch 300, a 2007 American film adaptation by Zack Snyder of the graphic novel of the same name by Frank Miller, a comic book that was not comic all the way. Both graphic novel and film staged a fictionalized reworking of the Battle of Thermopylae presenting King Leonidas (Gerard Butler) and 300 Spartans, muscular warriors who fought to their death against Xerxes and his massive Persian army. The film was a shot-for-shot adaptation of the comic book, similar to the film adaptation of Sin City, one of Miller's earlier graphic novels, although this one did not rely upon historical facts.

As a graphic novel (issued two years before 9/11), 300 had a foreword written to its 2007 re-issue by Professor Victor Davis Hanson, “National Review” columnist, holding that the intent was to "entertain and shock first, and instruct second" (March 22, 2007: 300 Fact or Fiction?). And in the opinion of its maker, as was mentioned in an MTV interview, 300 was just a fantasy film, “an opera not a documentary” (March 23, 2007) and a lot of American (neo) conservative voices repeated this statement. Is this film heavily ideologically charged or is this just a prejudice of a number of ‘purists’ who do not fully appreciate its artistic nature?

Zack Snyder's 300 (2007)

In an interview that was conducted before the Berlin Film Festival, Snyder confirmed that “no parallels between the film and the contemporary world were intended” (Michael Cieply, March 5, 2007; Jason Silverman, February 22, 2007). In the opinion of its director, the graphic novel is just a comic book, and the movie just a fantasy. In response to the outburst of criticism after the launching of the film, a Warner Bros spokesman stated that the film 300 “was a work of fiction inspired by the Frank Miller graphic novel and loosely based on a historical event. The studio developed this film purely as a fictional work with the sole purpose of entertaining audiences; it is not meant to disparage an ethnicity or culture or make any sort of political statement” (March 31, 2007). Further proof of innocence: like the comic book, the film adaptation emphatically used a character called Dilios as a narrator who showed the audience “that the surreal ‘Frank Miller world’ of 300 was told from a subjective perspective”, and consequently one simply had to assume and to accept that this Dilios was “a guy who knows how not to wreck a good story with truth” (quoted in a BBC News story, Resa Nelson, February 1, 2006: 300 Mixes History, Fantasy).

However, from its opening (March 7, 2007, Greece; March 9, 2007, United States), 300 was violently denounced by a lot of critics, scholars and politicians, as one of the most racially charged films of the last decades. It portrayed the Persians as a horde of barbarian monsters, representatives of a completely different world, all along Samuel P. Huntington’s well known, much debated, but still persisting theory of “The Clash of Civilizations”, which argued that cultural and religious differences within the next generations will be the primary sources for war and conflict rather than traditional causes, like politics, ideology, and economy. By a large number of people, this film confirmed anachronistic Western stereotypes of Asian and Persian cultures and illustrated a trend of accepted racism towards Middle-Easterners. Especially the unbridled reproduction of clichés and stereotypes seemed to have worried many critical voices. Television and film, they argued, are among the most powerful storytellers in culture as they constantly iterate, vary and consolidate images and roles that function as fundamental building stones in a given society. Among the major stereotypes, one noticed punctuated differences in skin, opposing white-skinned Spartans versus dark-skinned Persians, well trained Greek bodies versus faceless savages and demonically deformed Persians, their husband loving Spartan women versus Persian demonized lesbians and concubines, and to end with, as a symbol of Greek patriotism and male identity, Leonidas of Sparta, versus King Xerxes portrayed as an androgynous madman, covered with facial piercings and glittering jewels. Light versus darkness, human bodies versus monstrous elephants and rhinos, harmony versus deformation, solidarity and respect versus kneeling and prostration, a whole series of images was produced that easily could serve to vilify Arabs and Muslims in a contemporary post 9/11 atmosphere. Even when it was clear that the Persians in 300 never could be neither Arab nor Muslim, the temptation was great to identify them with those same groups in the wake of present day ‘clash of civilization’.

Gerad Butler as Leonidas (left) and Rodrigo Santoro as Xerxes (right) in Zack Snyder's 300 (2007)

Eventually, one only had to wait Frank Miller's interview on National Public Radio (NPR) on January 27, 2007, following President Bush’s “State of the Union” address, to have a clearer vision on the political intentions of his film (just prior to its release). Asked about the enemy, he answered: "Well, okay, then let’s finally talk about the enemy. For some reason, nobody seems to be talking about who we’re up against, and the sixth century barbarism that they actually represent. These people saw people’s heads off. They enslave women, they genitally mutilate their daughters, they do not behave by any cultural norms that are sensible to us. I’m speaking into a microphone that never could have been a product of their culture, and I’m living in a city where three thousand of my neighbours were killed by thieves of airplanes they never could have built". He also explained the upcoming work Holy Terror, Batman!, a story wherein Batman takes on Al-Qaeda, as: “It is, not to put too fine a point on it, a piece of propaganda […] Superman punched out Hitler. So did Captain America. That's one of the things they're there for”.

Obviously, one should not be surprised when many critics stated that 300 was pure ideology, western ideology at work in one of the best selling media products of the last years. A.O. Scott of the “New York Times” described 300 as “about as violent as Apocalypto and twice as stupid” and clearly referred to the plot’s racist undertones. In the “New York Post”, Kyle Smith wrote that it would have pleased "Adolf Boys" (March 9, 2009), and "Slate’s" Dana Stevens called it “a textbook example of how race-baiting fantasy and nationalist myth can serve as an incitement to total war” (March 8, 2009). Two elements in particular caused a strong reaction in Iran, Wikipedia holds – see its very detailed list of references on 300 in wikipedia.org/wiki/300_(film) – the film’s release on the eve of Persian New Year, and the common Iranian view of the Achaemenid Empire as “a particular noble page in their history” (see Brosius 2006). The Iranian Academy of Arts submitted a formal complaint against the movie to UNESCO and Iranian embassies in different countries protested its screening.

Three years later, an independent Iranian website IranDefense.net still took the time to update its attacks on the 300. It staged a great number of historians, classicists and journalists who have been engaged to correct the historical facts and figures, to defend the ancient Persian culture and to put the importance of Sparta in a more ‘realistic’ perspective. Using the same typographic devices as Zack Snyder’s poster, this Iranian website made it clear that media were an excellent device for distributing ideological messages. What the morning newspaper “Time” of Tuesday, March 1st, 2007, already had summarized “300 AGAINST 70 MILLION” (the population of Iran), had been taking up by the IranDefense website and was still used as a key of reinterpretation, only now the message had been sharpened, asking us how we would react when faced with the slogan:

300 Germans against a Million Jews.

Germans, tonight we dine in the Warsaw ghetto

Referring to the already mentioned book The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures, by Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin (1989), the IranDefense website presented a large number of slides, as striking as the one just presented, using the motto “The Persians Empire strikes back”. Excellent examples of how media today are used as ideological tools in a never ending propaganda war.

Interesting in this debate is the position taken by Victor Davis Hanson, neoconservative and strong supporter of the policies of George W. Bush, former professor of Classical History at California State University and co-author of some conservative books on classical Antiquity (1998 and 2001), books that criticized the introduction of new theories into the American curriculum (multiculturalism, theory of literature, deconstruction, feminism, ...) and held them responsible for the demise of classics. In Carnage and Culture (2001), he did some research on nine battles that had a crucial importance in Western history and that testified to an important characteristic of Western culture (starting with, of course, the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC). Its subtitle Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power revealed why it sold well in the wake of the 9/11 events. Actually, it did not need the explicit afterword Hanson added, suggesting that the US would win the War on terror precisely because of the reasons he already stated in his book. He believed indeed that the war against Iraq was a necessary initiative that would result in a laudable success.

In a statement after the Hollywood premiere of 300, he also reaffirmed that this movie had nothing to do with Iraq or contemporary events, at least in a direct sense, arguing that Miller's graphic novel was written well before the “war against terror” commenced under President Bush. He wrote an introduction for the accompanying book about the film and mentioned a number a reasons why 'purists' should not focus on its political dimensions. First of all, it was “not intended to be Herodotus Book 7, 209-236, but rather [was] an adaptation from Frank Miller's graphic novel, which itself [was] an adaptation from secondary work on Thermopylai. Purists should remember that when they see elephants and a rhinoceros”. “Second”, he mentioned, “in an eerie way, the film captures the spirit of Greek fictive arts themselves. Snyder and Johnstad and Miller are Hellenic in this sense: red-figure vase painting especially idealized Greek hoplites through 'heroic nudity'. Such iconographic stylization meant sometimes that armor was not included in order to emphasize the male physique. So too the 300 fight in the film bare-chested. In that sense, their oversized torsos resemble not only comic heroes, but something of the way that Greeks themselves saw their own warriors in pictures”. His third remark concerned the way “Snyder, Johnstad, and Miller have created a strange convention of digital backlot and computer animation, reminiscent of the comic book mix of Sin City. That too is sort of like the conventions of Attic tragedy in which myths were presented only through elaborate protocols that came at the expense of realism (three male actors on the stage, masks, dialogue in iambs, with elaborate choral metres, violence off stage, 1000-1600 lines long, etc. There is irony here”, he mentioned, referring to the opposite position taken by Oliver Stone's mega-production Alexander that “spent ten millions in an effort to recapture the actual career of Alexander the Great”. Surely “the 300 dispenses with realism at the very beginning, and thus shoulders no such burdens”.

Arguments like these are cheap and irrelevant. They allow a political and ideological use of Antiquity in any direction (fascist, national socialist, fundamentalist, neo-conservative...), since it always is just an adaptation of an adaptation, it always reflects in one way or another “the spirit of Greek fictive arts themselves”, or it always only concerns “protocols that came at the expense of realism”. In the meantime, films like these justify the “persistence of accepted racism” (see brokenmystic.wordpress.com/2009/02/17/).

3. Conclusions

In this article we briefly discussed three versions of Aischylos’ Persians that are far apart from each other. The first (Jelinek / Schlingensief) can be called posthumanist, as it deconstructs the languages of power and politics that shaped a European 'humanism' that today lost its (universal) appeal. At the very core of their concern is the question how art still can intervene in a period of constant dehumanization and elision of life.

Thiasos' 2006 staging of Persians saw its artistic director, Yana Zarifi, travel East in order to study the oral tradition of songs that shaped ancient and contemporary Persians. As she turned to the culture of ‘the other side’, she escaped the kind of binary and hierarchical thinking that rightly has been accused as Orientalism and chose for an anthropological and ritual analysis of processes that transform the heart.

The Snyder-Miller project illustrated what Jelinek has been warning for all her life: media covering has an immense impact on the way our thoughts, values and views of each other are shaped. Their graphic novel and movie were based upon an ideology that highlighted the Orientalist distrust of the Other.

Bibliography

Badmington 2000

Posthumanism (Readers in Cultural Criticism), Neil Badmington (editor), Palgrave, New York 2000

Lücke 2004

Bärbel Lücke, Zu Bambiland und Babel. Essay, in Elfriede Jelinek, Bambiland. Babel. Zwei Theatertexte, Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 2004

Bridges, Hall, Rhodes 2007

Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars: Antiquity to the Third Millennium, Emma Bridges, Edith Hall, and P.J. Rhodes (editors), Oxford 2007

Burn 1988

Andrew Robert Burn, Persia and the Greeks, London 1988

Brosius 2006

Maria Brosius, The Persians. An Introduction, London 2006

Cohen 2000

Not the Classical ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, Beth Cohen (editor), Leiden 2000

Davies 1997

Tony Davies, Humanism, London 1997

Decreus 2000

Freddy Decreus, The Oresteia, or the myth of the Western metropolis between Habermas and Foucault, in “Grazer Beiträge”, 23, 2000, pp. 1-21

Decreus, Kolk 2004

Rereading Classics in ‘East’ and ‘West’: Post-colonial Perspectives on the Tragic, Freddy Decreus, M. Kolk (editors), Gent 2004

Decreus 2006

Freddy Decreus, ‘Aeschylus’ Persians between “East” and “West”: A Tragedy between History, Ideology and Memory’, in Ninth International Symposium on Ancient Greek Drama, Nicos Shiafkalis (editor), Leukosia 2006, pp. 249-274

Eagleton 1991

Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An Introduction, London & New York 1991

Freeden 2003

Michael Freeden, Ideology: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford 2003

Goldhill 1990

Simon Goldhill, The Great Dionysia and Civic Ideology, in Nothing to do with Dionysos, John J. Winkler, Froma I. Zeitlin (editors), Princeton 1990, 97-129

Hall 1991

Edith Hall, Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy, Oxford 1991

Hall 1996

Edith Hall, Aeschylus Persians, Warminster 1996

Hall 1997

Edith Hall, The Sociology of Athenian Tragedy, in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy, Pat E. Easterling (editor), Cambridge 1997, pp. 93-126

Hall 2004

Edith Hall, Aeschylus, Race, Class, and War, in Edith Hall, Fiona Macintosh, and Amanda Wrigley (editors), Oxford 2004, 169-197

Hall 2007

Edith Hall, Aeschylus’ Persians via the Ottoman Empire to Saddam Hussein, in Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars, Emma Bridges, Edith Hall and P. J. Rhodes (editors), Oxford 2007, pp. 167-199

Hall 1997

Jonathan M. Hall, Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity, Cambridge 1997

Hall 2002

Jonathan M. Hall, Hellenicity: Between Ethnicity and Culture, Chicago 2002

Hanson, Heath 1998

Victor Davis Hanson, John Heath, Who Killed Homer? The Demise of Classical Education and the Recovery of Greek Wisdom, New York 1998

Hanson, Heath 2001

Victor Davis Hanson, John Heath, Bruce S. Thornton, Bonfire of the Humanities: Rescuing the Classics in an Impoverished Age, Wilmington, Delaware 2001

Hardwick 2006

Lorna Hardwick, Remodelling Receptions: Greek drama as Diaspora in Performance, in Classics and the Uses of Reception, Charles Martindale, Richard F. Thomas Martindale (editors), Wiley-Blackwell, New Jersey 2006, 204-215

Hardwick, Gillespie 2007

Classics in Post-Colonial Worlds, Lorna Hardwick, Carol. Gillespie (editors), Oxford 2007

Hardwick, Stray 2008

A Companion to Classical Receptions, Lorna Hardwick & Christopher Stray (editors), Oxford 2008

Harrison 2002

Thomas Harrison, Greeks and Barbarians, Edinburgh 2002

Harrison 2008

Thomas Harrison, "Respectable in Its Ruins”: Achaemenid Persia, Ancient and Modern, in A Companion to Classical Receptions, Lorna Hardwick & Christopher Stray (editors), Oxford 2008, 50-61

Holland 2005

Tom Holland, Persian Fire. The First World Empire and the Battle for the West, London 2005

Hornblower 2001

Simon Hornblower, Greek and Persians: West against East, in War, Peace and World Orders in European History, Anja V. Hartmann & Beatrice Heuser (editors), London, 2001, 48-61

Irigaray 2002

Luce Irigaray, Between East and West. From Singularity to Community, New York 2002

Kabbani 1986

Rana Kabbani, Europe’s Myths of Orient: Devise and Rule, Houndsmills, London 1986

Koen 2006

Benjamin D. Koen, Musical Healing in Eastern Tajikistan. Transforming Stress and Depression through Falak Performance, in “Asian Music”, 37, 2006, 2, 58-83

Koen 2008

Benjamin D. Koen, Beyond the Roof of the World. Music, Prayer, and Healing in the Pamir Mountains, Oxford 2008

Koerner 2010

Morgan Koerner, Media Play: Intermedial Satire and Parodic Exploration in Elfriede Jelinek and Christoph Schlingensief’s Bambiland, in Christoph Schlingensief. Art without Borders, Tara Forrest, Anna Teresa Scheer (editors), Chicago 2010, 153-168

Kristeva (1988)

Julia Kristeva, Etrangers à nous-mêmes, Fayard, Paris 1988

Leezenberg 2007

Michiel Leezenberg, From the Peloponnesian War to the Iraq War: a Post-Liberal Reading of Greek Tragedy, in Classics in Post-Colonial Worlds, Lorna Hardwick, Carol Gillespie (editors), Oxford 2007, 265-285

Levene 2007

David S. Levene, Xerxes goes to Hollywood, in Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars: Antiquity to the Third Millennium, Emma Bridges, Edith Hall, and P.J. Rhodes (editors), Oxford 2007, 383-421

Macfie 2000

Orientalism: A Reader, Alexander Lyon Macfie (editor), Edinburgh 2000

Miller 1997

Margareth C. Miller, Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity, Cambridge 1997

Rosenbloom 1995

David Rosenbloom, Myth, History, and Hegemony in Aeschylus, in History, Tragedy, Theory, B. Goff (editor), Austin, TX 1995, 91-130

Said [1978] 1995

Edward W. Said, Orientalism. Western Conceptions of the Orient, London [1978] 1995

Sieg 2008

Katrin Sieg, Choreographing the Global in European Cinema and Theater, New York 2008

English abstract

In this essay, Freddy Decreus establishes a relationship between three contemporary movies – Elfriede Jelinek's Bambiland (2003), Yana Zarifi's Persians (2006) and Zack Snyder's 300 (2007) – with Aeschylus’ Persians.

keywords | Cinema; Persians by Aeschylus; Bambiland by Elfriede Jelinek; Persians by Yana Zafiri; 300 by Zack Snyder

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: F. Decreus, Elfriede Jelinek's Bambiland (2003), Yana Zarifi's Persians (2006) and Zack Snyder's 300 (2007), three different ways to invent ourselves, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 87, gennaio-febbraio 2011, pp. 26-41. | PDF