Raffigurazioni vascolari e rappresentazioni teatrali

Oliver Taplin, traduzione a cura di Anna Banfi*

English abstract

Oliver Taplin, About Pots & Plays, English full text

.jpg)

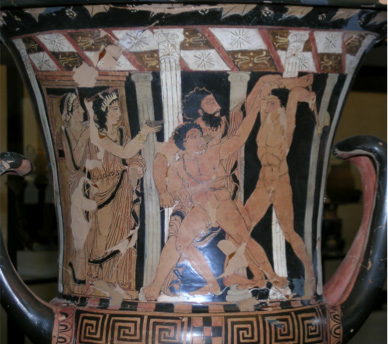

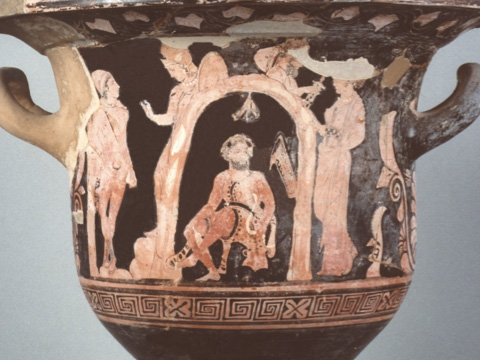

1 | Assassinio di Neottolemo a Delfi, cratere apulo a volute, attribuito al Pittore dell’Ilioupersis, Milano, Collezione H.A. – Collezione Banca Intesa, ca. 360 a.C.

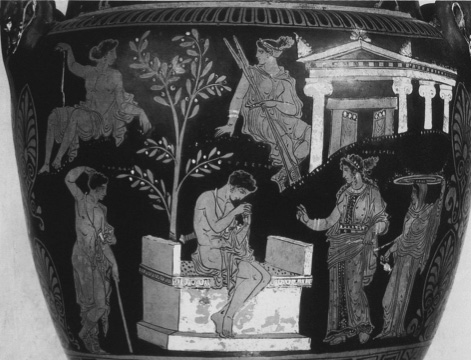

2 | Medea sul carro del Sole, dopo l’assassinio dei figli, cratere lucano a calice, vicino allo stile del Pittore di Policoro, Cleveland, Museum of Art, ca. 400 a.C.

3 | Medea fugge sul carro del Sole, mentre Giasone brandisce la spada contro di lei, hydria lucana, attribuita al Pittore di Policoro, Policoro, Museo Nazionale della Siritide, ca. 400 a.C.

4 | Incontro tra Oreste e Ifigenia, cratere apulo a volute, attribuito al Pittore dell’Ilioupersis, Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, ca. 360 a.C.

.jpg)

5 | Assassinio di Neottolemo a Delfi, cratere apulo a volute, attribuito al Pittore dell’Ilioupersis, Milano, Collezione H.A. – Collezione Banca Intesa, ca. 360 a.C.

6 | Ippolito cerca di domare i cavalli imbizzarriti alla vista del toro divino (nella fascia superiore: gruppo di divinità) cratere apulo a volute, attribuito al Pittore di Dario, Londra, British Museum, ca. 340 a.C.

7 | Addio di Alcesti, loutrophoros apula, vicino allo stile del Pittore di Laodamia, Basilea, Antikenmuseum, ca. 340 a.C.

8 | Prometeo liberato da Eracle, cratere apulo a calice, attribuito al Pittore di Branca, Berlino, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, ca. 340 a.C.

9 | Oreste nell’atto di uccidere la madre Clitennestra, anfora, attribuita al Pittore di Würzburg,Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum, ca. 330 a.C.

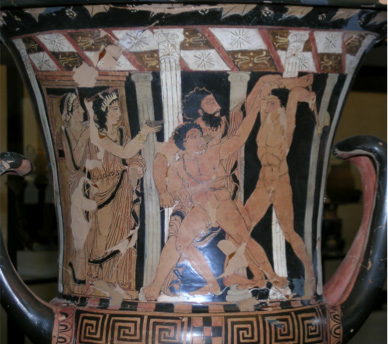

10 | Anfione e Zeto nell’atto di uccidere il tiranno Lico, cratere siceliota a calice, attribuito al Pittore di Dirce, Berlino, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, ca. 380 a.C.

11 | La caverna di Filottete sull’isola di Lemno, cratere siceliota a campana, attribuito al Pittore di Dirce, Siracusa, Museo Archeologico Regionale “Paolo Orsi”, ca. 380 a.C.

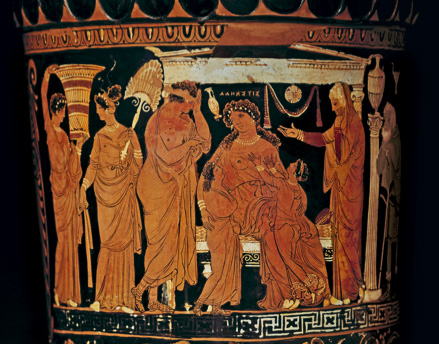

12 | Adrasto e le sue figlie, cratere siceliota a calice, attribuito al Gruppo di Adrasto, Lipari, Museo Eoliano, ca. 340 a.C.

13 | Scena tragica, cratere siceliota a calice, attribuito al Pittore di Capodarso (Gruppo Gibil Gabib), Caltanissetta, Museo Civico, ca. 330 a.C.

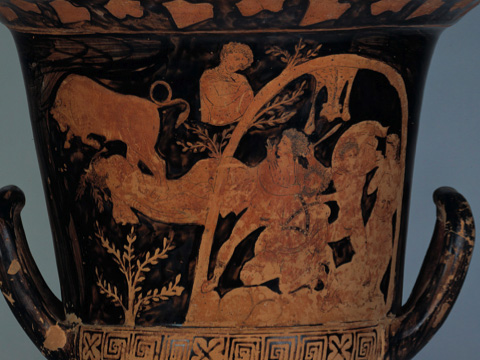

14 | Il pastore di Corinto, Edipo, Giocasta e le figlie, cratere siceliota a calice, attribuito al Gruppo Gibil Gabib, probabilmente al Pittore di Capodarso, Siracusa, Museo Archeologico Regionale “Paolo Orsi”, ca. 330 a.C.

L’interazione tra teatro e arti visive è stato un fenomeno di epoca in epoca molto variabile e non continuativo. Se prendiamo ad esempio il XVIII secolo, vedremo che in questo periodo è stata prodotta una grande abbondanza di pitture e stampe con la raffigurazione di attori in scena; invece in età shakespeariana (sfortunatamente) la produzione di questo genere di opere è pressoché nulla.

Un ricco e in parte trascurato patrimonio di raffigurazioni di scene teatrali proviene però dal mondo greco del IV secolo a.C. Ci sono più di cento scene di commedie dipinte su vasi, e un numero ancora maggiore di scene mitologiche suggestivamente collegabili alla loro versione teatrale tragica. In Comic Angels, pubblicato nel 1993, ho concentrato l’attenzione sulla commedia: della tragedia mi sono invece occupato nel mio ultimo libro, Pots&Plays. L’obiettivo che mi prefiggo qui è quello di darvi un’idea di come ho affrontato questo tema.

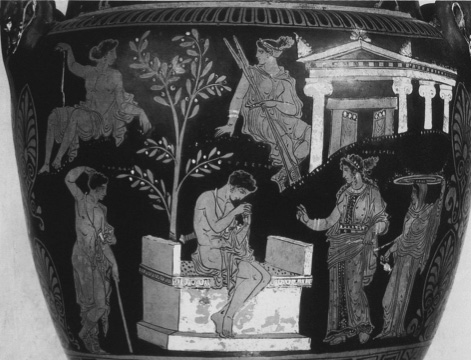

Prendiamo ad esempio una pittura vascolare, databile al 360 a.C. circa, che presenta una stretta relazione con una rappresentazione teatrale (fig. 1). La scena è con grande evidenza semantizzata come Delfi, cosa che è segnalata da diversi elementi: l’omphalos decorato (la pietra che indicava l’ombelico del mondo); la Sacerdotessa raffigurata in alto a sinistra e Apollo a destra, sopra il cui capo è scritto il suo nome (fatto questo, abbastanza diffuso). In basso a sinistra c’è un giovane che impugna una lancia, a destra Oreste (con nome) con la spada sguainata, e, al centro, Neottolemo (con nome) inginocchiato presso l’altare e già mortalmente ferito. Questa scena rappresenta dunque un mito molto conosciuto: l’assassinio a Delfi di Neottolemo, figlio di Achille. Da questo mito è nato anche il modo di dire “nemesi di Neottolemo” perché lo stesso Neottolemo aveva ucciso il vecchio Priamo proprio presso l’altare di Zeus a Troia. Ma perché dovrebbe esserci una qualche ragione per collegare questa raffigurazione alla tragedia? Può la tragedia chiarire la lettura della raffigurazione?

Prima di affrontare questi temi, è necessario stabilire alcune coordinate cronologiche e geografiche: il periodo che prendiamo in considerazione è il secolo che va dal 420 al 320 a.C. circa; il luogo sono le colonie greche della Sicilia e del Sud Italia, quel territorio conosciuto come Magna Grecia, e in particolare l’Apulia (l’attuale Puglia). La fondazione della maggior parte di queste colonie risale a un’epoca antecedente al 650 a.C. e ciò comporta che queste comunità avevano (già/nel V-IV secolo) un assetto istituzionale solido, un buon livello di evoluzione economica e culturale: sarebbe un errore dunque pensare a queste colonie come a una situazione provinciale, di marginalità rispetto alla madrepatria. Intorno al 430 a.C. nella Grecia occidentale si registra una ricca produzione di ceramica a figure rosse che sostituisce le importazioni da Atene, che aveva detenuto per più di un secolo il monopolio della produzione di ceramica di alta qualità. Più o meno nello stesso periodo il teatro tragico e comico inizia a diffondersi anche fuori dalla città di Atene, incontrando terreno fertile in tutto il mondo greco. I più grandi tragediografi del V sec. a.C. (e in particolare Euripide) rimangono i ‘classici’ più rappresentati, ma continuano ad essere prodotte anche nuove tragedie – e non solo ad Atene. Vengono creati nuovi edifici teatrali, vengono reclutate compagnie teatrali e nuovi drammaturghi e attori, e in modo significativo proprio dalla Magna Grecia.

Per i Greci d’Occidente – e probabilmente anche per i loro vicini indigeni Italici – la ceramica finemente decorata e il teatro tragico coesistevano come opere di forti e nuovi soggetti, che ben si inserivano nel loro mondo culturale, artistico, estetico ed emotivo. Eppure, nonostante questo sorprendente sincronismo, negli ultimi trenta anni c’è stata una tendenza diffusa a rifiutare qualsiasi tipo di connessione tra pittura vascolare e teatro, e a tenere nettamente separate queste due forme d’arte, considerandole autonome l’una dall’altra. Alcuni studiosi affermano che la pittura vascolare che rappresenta Neottolemo a Delfi è un’immagine perfettamente autosufficiente e che – molte grazie, ma non vi è alcun bisogno di appellarsi alla tragedia per chiarirne il significato. Il titolo di un libro pubblicato di recente, The Parallel Worlds of Classical Art and Text, ben sintetizza la posizione di coloro che rigettano qualsiasi infiltrazione tra letteratura e arte. Ironia vuole che questo scetticismo sia coinciso con il periodo in cui sono stati pubblicati un gran numero di vasi prima inediti, potenzialmente molto significativi (circa metà dei 109 vasi analizzati in Pots&Plays sono di recente acquisizione critica). Molti di questi vasi, provenienti soprattutto dalla Puglia, sono stati scavati e poi esportati illegalmente. Ma, in un modo o nell’altro, essi sono ora noti e possono essere studiati e interpretati.

Due le vie principali che seguirò per contrastare la posizione di chi nega l’interazione tra teatro e pittura. In primo luogo, vorrei specificare che per me non si tratta di una questione di priorità o di superiorità: le pitture vascolari non sono ‘illustrazioni’ di scene teatrali, e neppure ‘sono ispirate’ dalle tragedie. Le due forme d’arte coesistono e si influenzano a vicenda: si tratta di arricchimento reciproco, non di dipendenza. In secondo luogo, intendo dimostrare che la tragedia, in quel periodo e in quei luoghi, lungi dall’essere un’esperienza elitaria e minoritaria, un testo accessibile solo a un numero limitato di lettori privilegiati, era invece uno spettacolo a cui assistevano ogni anno centinaia di migliaia di spettatori – un’esperienza pervasiva e condivisa. E perché queste persone avrebbero dovuto tenere l’esperienza del mito che facevano a teatro separata e distinta dall’esperienza del mito che facevano vedendo una pittura, soprattutto se tra queste rappresentazioni c’erano punti di contatto e connessioni precise?

La mia tesi di fondo è che la tragedia sia un mezzo (se non il mezzo principale) attraverso cui, in questo periodo, la conoscenza delle storie mitologiche si diffonde in tutta la Grecia. In alcuni casi possiamo essere abbastanza certi del fatto che alcune versioni del mito erano una vera e propria invenzione dei tragediografi ateniesi del V sec. a.C. In quel caso la pittura vascolare è necessariamente legata – in maniera più o meno stretta – alla tragedia. La questione è: per chi assisteva a uno spettacolo risultava potenziato l’apprezzamento della pittura vascolare? Conviene fare la prova mediante un esempio.

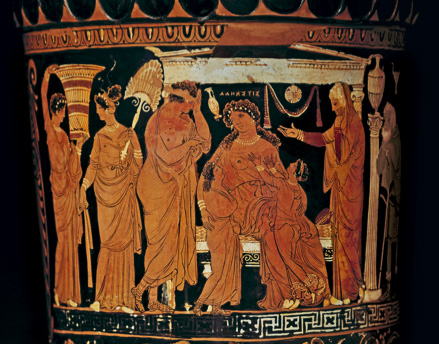

Questo splendido vaso che rappresenta Medea sul carro del Sole risale al 400 a.C. circa (fig. 2), cioè solo 30 anni dopo la prima messa in scena della famosa Medea di Euripide (Euripide muore nel 406).

Anche quest’altro vaso (fig. 3), portato alla luce nel 1963 a Policoro/Herakleia, risale più o meno allo stesso periodo, e, anche se di qualità considerevolmente più semplice del precedente, presenta una iconografia molto simile. È pressoché certo che fu proprio Euripide a inventare la versione del mito secondo cui Medea stessa uccise i propri figli, come vendetta contro l’infedeltà di Giasone; sempre a Euripide è attribuibile l’invenzione della fuga di Medea sul carro divino del Sole – padre di suo padre. E ciò che più conta è che la scena finale ideata da Euripide ruota attorno al potere superiore di Medea che con il carro del Sole si solleva sopra Giasone, il quale resta sotto di lei, a terra, a protestare impotente. Questa dinamica spaziale conferisce senza dubbio una potenza maggiore allo schema compositivo della pittura vascolare. Ci sono, certo, innegabili differenze tra pittura vascolare e dramma – tra le più importanti il fatto che nella tragedia di Euripide i bambini stanno sul carro con Medea – ma esse non sono in alcun modo prevalenti rispetto alle concordanze. La pittura non ha bisogno della tragedia, ma il suo significato aumenta agli occhi di coloro che hanno assistito alla rappresentazione di quel particolare episodio.

Potremmo dire la stessa cosa di questo vaso databile al 360 a.C. circa (fig. 4) che ritrae Ifigenia come una sacerdotessa e suo fratello Oreste (che ancora non si è identificato con lei) seduto sull’altare, in attesa di essere sacrificato ad Artemide Tauria. Tutta questa storia è un’invenzione di Euripide, e il vaso assume un significato molto maggiore agli occhi di chi aveva assistito alla rappresentazione della sua tragedia, l’Ifigenia in Tauride. Si è colpiti dalla somiglianza tra questo schema compositivo e quello che lo stesso artista adotta per il cratere con la scena di Neottolemo a Delfi (fig. 5, fig. 1). Ma in questo caso si tratta non propriamente di aver visto questa scena rappresentata, ma di averla sentita narrare in scena nella versione tragica euripidea. A quanto ci è dato di sapere, è stato Euripide per primo, nella sua Andromaca, a introdurre Oreste nella storia della morte di Neottolemo. In quella tragedia, il Messaggero racconta del vile agguato che Oreste organizza ai danni di Neottolemo mentre, senza alcun sospetto, sta consultando l’oracolo di Delfi. La pittura ha senso anche senza il dramma, ma è la versione euripidea che dà un maggiore significato alla presenza di Oreste e al fatto che sempre Oreste si stia nascondendo dietro l’omphalos. Questa scena è rappresentata su un vaso che viene classificato come cratere a volute (una coppa per mescere il vino, caratterizzata da due anse a volute che partono dall’orlo del vaso). Si tratta del tipo di vaso più utilizzato in Apulia, per la rappresentazione di scene mitologiche: nel IV sec. a.C. vengono realizzati crateri a volute sempre più grandi (vi è addirittura un esemplare che misura 57 cm di altezza) e sempre più decorati, con una predilezione per l’uso dei colori bianco, giallo e porpora.

Questo genere di ceramica e pittura monumentale raggiunge il suo picco massimo nel terzo quarto del IV sec. a.C.; il suo massimo esponente è un artista molto fecondo e creativo, conosciuto con il nome di ‘Pittore di Dario’. Potete vedere qui un esempio tipico del suo lavoro, un cratere alto più di un metro (fig. 6). Proprio come viene narrato dal Messaggero nella tragedia euripidea Ippolito, il giovane cerca di domare i suoi cavalli che si sono imbizzarriti per l’apparizione del toro divino. Ci sono due elementi che sono comuni nelle rappresentazioni in relazione con la tragedia. Il primo è rappresentato dalla curva figura di anziano sulla sinistra: si tratta della figura maschile, spesso presente, del precettore (paidagogos, in greco); in precedenza il Pedagogo aveva cercato invano di mettere in guardia Ippolito dal suo atteggiamento arrogante con la dea Afrodite. Il secondo elemento è il ‘fregio’ di divinità posto in alto: è da notare che, nella rappresentazione-tipo di questo elemento, le divinità sono spesso rappresentate in un atteggiamento serenamente distaccato dalla terribile tragedia umana che si svolge sotto di loro.

Questo vaso, esattamente come quelli in relazione con Andromaca e Ifigenia in Tauride, proviene dalla Apulia. Si tratta della raffigurazione dell’addio di Alcesti (fig. 7), un altro grande successo di Euripide (notate, ancora una volta, la figura del Pedagogo). E similmente anche questa raffigurazione di Prometeo incatenato a una roccia (fig. 8) e che allude probabilmente al Prometeo Liberato, una tragedia per noi perduta di Eschilo. Anche a Poseidonia/Paestum c’era una scuola di pittori la cui opera mostra una chiara conoscenza della produzione tragica.

L’area geografica da cui proviene una pittura vascolare di più bassa qualità, e meno direttamente relazionabile al teatro, è probabilmente quella intorno al Golfo di Napoli, la zona cioè della Campania che ha come centro Capua. Anche da questa zona provengono però alcuni reperti interessanti: per esempio questo vaso di piccole dimensioni su cui è raffigurato Oreste nell’atto di aggredire la madre Clitennestra (fig. 9). Oltre alla Furia (o Erinni), con un serpente intorno al braccio, in alto a destra, simbolo delle maledizioni materne che inseguono Oreste proprio come in Eschilo, osservate il modo in cui Clitennestra offre il proprio seno scoperto. Nelle Coefore di Eschilo, Clitennestra cerca invano di distogliere Oreste dall’ucciderla, proprio mostrandogli “questo petto” che lo ha nutrito quando era bambino. Ancora una volta, dunque, l’immagine assume maggiore significato agli occhi di chi conosce la tragedia.

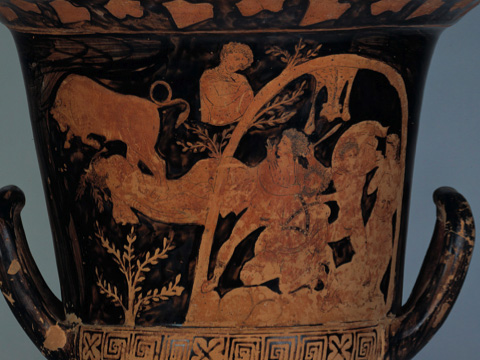

Da molti punti di vista l’area geografica più interessante nella produzione di pittura vascolare in relazione con la tragedia è la Sicilia. Le raffigurazioni mitologiche provenienti dalla Sicilia sono spesso vicine alle pratiche del teatro, e rivelano e sfruttano la conoscenza di una particolare tragedia e il collegamento con essa. Il legame è evidente soprattutto per le pitture vascolari a partire dalla seconda metà del IV sec. a.C., ma osservate questo bel cratere databile dopo il 380 a.C. (fig. 10).

La scena rappresenta Anfione e Zeto, i figli di Antiope, nell’atto di uccidere il tiranno Lico: sulla sinistra, nel frattempo, un toro selvaggio trascina via il corpo della crudele regina Dirce. Questa è la stessa scena contenuta in un papiro che riporta un frammento dell’Antiope di Euripide, dal quale sappiamo che la scena dell’assassinio veniva mostrata grazie all’uso dell’ekkyklema, il palcoscenico rotante, e che veniva interrotta dall’intervento di Hermes, che compariva ex machina. La composizione della pittura vascolare sembra risentire dell’utilizzo di queste macchine sceniche. Ancora, quest’altra scena (fig. 11), dipinta dallo stesso pittore autore della precedente, su un vaso portato alla luce nel 1915 durante gli scavi presso la necropoli di Fusco, rappresenta una caverna, dimora di Filottete, nel momento in cui fu abbandonato sull’isola di Lemno: dunque, sebbene probabilmente anche questa scena debba essere collegata a una tragedia, non si tratta del Filottete di Sofocle.

Come dicevo, alcuni vasi siciliani più tardi presentano un legame più chiaro ed esplicito con il teatro. Ad esempio, questo vaso che proviene da Lipari (fig. 12) mostra una scena violenta che avviene di fronte a colonne dipinte che sembrano quelle di un fondale scenico. Non siamo in grado di dire a quale particolare tragedia facesse riferimento questa pittura vascolare, come non siamo in grado di riconoscere la scena nemmeno per questo vaso (fig. 13), ritrovato a Capodarso e databile al 330 a.C. circa.

Come potete notare, ci sono quattro figure che si trovano su un piccolo palcoscenico – qualcosa di simile si trova su molti vasi che ritraggono scene comiche, mentre questo elemento non risulta così ben rappresentato su nessun altro esemplare che possa essere messo in relazione con la tragedia. Probabilmente non si tratta di una raffigurazione realistica di un palcoscenico, né dell’istantanea di un vero e proprio momento di una tragedia, ma piuttosto è chiara ed evidente la volontà di richiamare alla mente il teatro e la rappresentazione di un dramma.

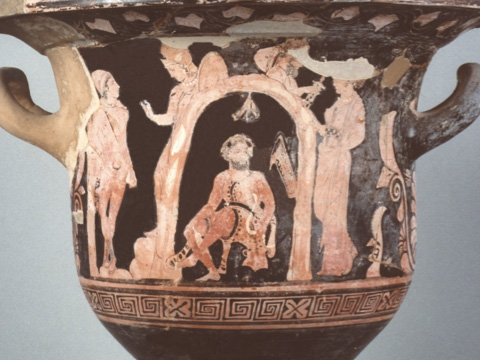

Infine, ecco l’esemplare più importante per i ragionamenti che stiamo facendo: si tratta del frammento di un cratere a calice, databile agli anni trenta del 300 a.C., dipinto dallo stesso pittore del precedente e portato alla luce nel 1969 a Siracusa (fig. 14).

Il vaso segnala un allestimento scenico mediante le colonne e il palco su cui si trovano i personaggi. E in questo caso la tragedia non è sconosciuta. La maggior parte degli studiosi – me compreso – ritiene che questa pittura vascolare evochi una scena dell’Edipo Re di Sofocle. Si tratta del momento in cui il vecchio pastore di Corinto racconta a Edipo di quando gli fu consegnato, bambino, sul Monte Citerone, e della sua decisione di consegnarlo a Polibo, re di Corinto. Edipo sembra perplesso, mentre, sulla destra, Giocasta si copre il volto con il mantello: è proprio questo il momento in cui per la prima volta comprende la verità. Questa raffigurazione, dunque, cattura un particolare momento del dramma che poteva essere colto dallo spettatore che assisteva alla rappresentazione, ma che non è esplicitato nel testo recitato a questo punto della tragedia. Il fascino di questo vaso è diretto a chi ha visto la tragedia a teatro piuttosto che a chi ha solo letto il testo o ne ha sentito parlare. Singolare che Aristotele – che nella sua Poetica insiste sul fatto che si possa fare piena esperienza dell’effetto tragico di Edipo anche senza avere visto la tragedia – scelga come esempio proprio questo particolare momento della rappresentazione (Poetica 1452a24).

Rimane infine da chiedersi quale fosse la funzione di questi enormi vasi e che cosa la tragedia avesse a che fare con i contesti per i quali essi venivano realizzati. Non ci sono dubbi sul fatto che la maggior parte di questi vasi (se non vogliamo dire tutti) venivano realizzati per occasioni funebri, come manifestazioni del lutto, per essere poi sepolti insieme al defunto (questo è il motivo per cui si sono conservati nelle tombe). Una delle spiegazioni del motivo per cui venivano scelte scene tragiche da rappresentare su questi vasi potrebbe essere il fatto che il defunto era un grande estimatore del teatro tragico. Ma queste angoscianti raffigurazioni di conflitti e disastri umani difficilmente avrebbero potuto essere di conforto per coloro che piangevano la morte di una persona cara. Alcuni studiosi hanno cercato di sottolineare particolari aspetti delle vicende rappresentate, che potessero in qualche modo recuperare dal mito tragico il senso di una riconciliazione o di una conclusione positiva.Ma molte delle storie raffigurate sono troppo truci, orribili e lontane dalla possibilità di una riconciliazione finale, per soddisfare questo tipo di spiegazione in certo qual modo ‘sentimentale’. E allora: in che modo le tragedie, nel loro insieme, con tutti gli aspetti angoscianti e tenebrosi, potevano rappresentare un elemento consolatorio per il dolore provocato da un lutto?

La mia tesi è che una sorta di ‘conforto estetico’ potesse essere tratto da queste raffigurazioni, l’idea che la vita umana, pur nelle difficoltà e nel dolore, lasci comunque dietro di sé tracce di ‘bellezza’. Le storie dei miti sono impersonate da figure che hanno una forza e una grandezza di spirito maggiore rispetto ai comuni mortali, e sono spesso coinvolte in sofferenze peggiori, in disgrazie maggiori e in sconvolgimenti più pesanti rispetto a quelli che normalmente affronta un uomo – a meno che non sia particolarmente sfortunato. E queste storie sono materia per la poesia e materia per la pittura. Quello che fanno gli artisti che realizzano le pitture vascolari è prendere queste storie del ‘peggio della vita’ e tradurle in immagini che hanno forma, colore, equilibrio e proporzione. La pittura diventa essa stessa opera della bellezza. Non si tratta del fatto che gli artisti del IV sec. a.C. vogliano censurare ciò che è sgradevole. Rappresentano continuamente dolore e violenza, ferite e cadaveri, ma tutti questi elementi sono ritratti in un modo che conserva una certa distaccata serenità. Per quanto una storia possa essere sgradevole, la pittura non lo è mai. Queste raffigurazioni, viste all’interno del loro contesto in occasione dei funerali, sollecitavano la capacità umana di vedere forma e colore anche al culmine della sofferenza, anche nel momento di lutto più intenso e profondo. Questo è il motivo per cui questi vasi fanno riferimento alla tragedia e non a qualcosa di più ordinario, allettante e confortante. Il vero conforto, se deve agire in profondità, ha bisogno di qualcosa che vada oltre alla mera consolazione.

Nello sperimentare il tragico a teatro, gli spettatori si trovano di fronte al colmo dell’orrore, a crisi di instabilità e a prove di resistenza, ovvero di fronte a esperienze che nessuno si augurerebbe mai di dover affrontare nella vita reale. Ma poi alla fine dello spettacolo, nessuno ne esce morto o traumatizzato. L’esperienza dell’abisso, il viaggio nell’instabilità a teatro sono vissuti – visti, ascoltati – in una forma che ha bellezza. La poesia, la danza, la musica, i costumi e le voci, l’armonia di suono e azione collaborano a rendere l’esperienza teatrale un momento da cui l’uomo può trarre non abbattimento e debolezza, ma energia. Al funerale il morto è realmente morto, e niente, neppure il più grande dolore, può farlo resuscitare. E la vita del defunto, come tutte le nostre vite, sarà stata caratterizzata da delusioni, inganni, momenti tristi, dolori e angosce. Quello che fanno questi splendidi vasi è di distillare bellezza dalla confusione di tutta questa nostra vita umana. Le pitture vascolari, le tragedie, i vasi e gli spettacoli interagiscono al fine di rinnovare nell’uomo la forza di resistere alla morsa delle tenebre.

* Il contributo qui pubblicato è la traduzione di una conferenza tenuta presso l’Università di Catania il 18 gennaio 2010 da Oliver Taplin, Professore di Lingue e Letterature Classiche e Direttore dell’Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama all’Università di Oxford.

.jpg)

1 | Death of Neoptolemos at Delphi, Apulian volute-krater, ca. 360s, attributed to the Ilioupersis Painter, Milano, Collezione H. A. - Banca Intesa Collection.

2 | Medea on the snake-chariot, Lucanian calyx-krater, ca. 400, close to the Policoro Painter, Cleveland, Museum of Art.

3 | Medeia on the snake-chariot, Lucanian hydria, ca. 400, attributed to the Policoro Painter, Policoro, Museo Nazionale della Siritide.

.jpg)

4 | Meeting of Orestes and Iphigeneia, ca 360s, Apulian volute-krater, attributed to the Ilioupersis Painter, Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

5 | Death of Neptolemos at Delphi, Apulian volute-krater, ca. 360s, attributed to the Ilioupersis Painter, Milano, Collezione H.A. – Banca Intesa Collection.

6 | Hippolytos trying to control his horses, Apulian volute-krater, ca. 340s, attributed to the Darius Painter, London, British Museum.

7 | Death of Alkestis, Apulian loutrophoros, ca. 340s, near the Laodamia Painter, Basel, Antikenmuseum und Sammlung Ludwig.

8 | Prometheus released by Herakles, Apulian calyx-krater, ca. 340s, attributed to the Branca Painter, Berlin, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

9 | The killing of Klytaimestra by Orestes, Paestan neck-amphora, ca. 330s, attributed to the Painter of Würzburg, Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum.

10 | Killing of Lykos, Sicilian calyx-krater, ca. 380s, attributed to the Dirce Painter, Berlin, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

11 | Philoctetes in Lemnos, Sicilian bell-krater, ca. 380s, attributed to the Dirce Painter, Siracusa, Museo Archeologico Regionale “Paolo Orsi”.

12 | Adrastos and his daughters, Sicilian calyx-krater, ca. 340s, belonging to the Adrastos Group, Lipari, Museo Eoliano.

13 | Tragedy-related scene, Sicilian calyx-krater, ca. 330s, the Capodarso Painter (Gibil Gabib Group), Caltanissetta, Museo Civico.

14 |The old man from Corinth, Oedipus, Jokasta and their daughters, Sicilian calix-krater, ca. 330s, attributed to the Gibil Gabib Group, probably the Capodarso Painter, Siracusa, Museo Archeologico Regionale “Paolo Orsi”.

Interplay between theatre and the visual arts has been highly variable and sporadic over the ages. While the eighteenth century produced a plethora of paintings and engravings of actors in performance, for example, the era of Shakespeare produced hardly anything (unfortunately). A rich, and relatively neglected, storehouse of theatre-related painting comes from the ancient Greek world in the fourth century BC. There are well over 100 scenes of comedies in performance surviving on painted ceramic vessels, and even more scenes of mythological stories which are fascinatingly related to their theatrical tellings in tragedy. I looked at Comedy in my book Comic Angels (1993): now in Pots&Plays I have turned to Tragedy. My aim today is to give you some idea of how I have set about the subject in that book.

Take, for example, this strikingly “dramatic” painting dating from about the 360s (fig. 1). The scene is emphatically set at Delphi, as is marked by several signs, including the decorated omphalos (navel-stone), the Priestess in the upper left and Apollo himself to the right, with his name written in above his head – quite a common feature. To the left below is a young man brandishing a spear, to the right Orestes (named) with his sword drawn, and in the centre, kneeling on the altar, Neoptolemos (named), already seriously wounded. This is, then, the killing of Neoptolemos, son of Achilles, at Delphi, a well-known myth – there was even a proverb “Neoptolemean revenge”, because he had killed the aged Priam at the altar of Apollo at Troy. So, why should there be any reason to connect this painting with tragedy? Could tragedy do anything to help its appreciation?

Before facing these questions, some chronological and geographical setting. The time is roughly the century between 420 and 320 BC; the place is the Greek West, the Hellenic communities in Sicily and around the coasts of southern Italy, often known as Magna Graecia, and especially Apulia (modern Puglia). Most of the Greek cities in this part of the world had been founded way back before 650, so these are well-established communities, many of great wealth and culture – it would be a mistake to think of them as provincial or cut-off.

Around 430 BC a flourishing industry in red-figure painted pottery grew up in the Greek West, displacing the Athenian imports which had held a virtual monopoly of high-quality ceramics for more than a century. At just the same time the spectacular and sensational new art-form of Theatre, both tragedy and comedy, was spreading out from its metropolis of Athens to the whole of the scattered Greek world. The great tragedians of fifth century Athens, especially Euripides, remained the most popular “classics”; but new tragedies continued to be produced, and not only in Athens. Theatre-buildings and travelling troupes developed, new playwrights and actors were recruited, not least from Magna Graecia. For the Greeks in the West – and quite possibly for their closely associated indigenous Italian neighbours also – fine painted pottery and tragic theatre coexisted as powerful and fresh subjects of appreciation within their cultural, artistic and emotional worlds.

Yet, despite this striking synchronism, there has been a strong tendency in the last 30 years or so to reject any claimed connections between vase-painting and theatre, to keep the two art-forms separate and autonomous. “Neoptolemos at Delphis – some scholars would say – is a perfectly complete picture without any help from tragedy, thankyou”. The title of a recent book, The Parallel Worlds of Classical Art and Text, epitomises this reaction against seeing the “infiltration” of literature in art – or vice-versa. It is an irony that this scepticism has coincided with the first publication of a very large number of possibly relevant pots (nearly half of the 109 pots discussed in detail in Pots and Plays are recent accessions). Many of these have been illegally excavated and exported, especially from Puglia; but, for better or worse, they are now known, and crying out for interpretation.

I counteract this trend away from interrelating theatre and painting in two main ways. Firstly I do not treat the issue as a matter of priority or superiority: the pictures are not “illustrations” of theatre, nor are they “inspired by” tragedies: the two coexist and inform each other; it is a matter of mutual enrichment not of dependence. Secondly I show how tragedy at this time and place is by no means a minority or “elite” experience: far from being a “text”, accessible only to privileged readers, it is a performance seen by hundreds of thousands very year, a pervasive shared experience. Why should people keep their experiences of myths in the theatre compartmentalised separately from their viewing of myths in paintings, especially if there are signals or links between them?

My thesis is that tragedy was one of the main ways, if not the main way, that the mythological stories were known throughout Greece in this period. In some cases we can be pretty sure that certain versions were actually invented by the great tragedians of fifth-century Athens. In that case the painting is necessarily connected, more or less closely, to the tragedy. The question is: would seeing the play in performance enrich the appreciation of the painting? Best to put this to the test of an example.

This splendid vessel showing Medea in the chariot of the Sun was painted as early as 400 BC (fig. 2) – that is only some 30 years after the first performance of Euripides’ celebrated tragedy Medea (Euripides died in 406). And this vase (fig. 3), excavated at Policoro/Herakleia in 1963, is of a similarly early date, and, while considerably simpler, has in fact very much the same iconography.

Now, it is near certain that Euripides actually invented the story that Medea herself killed her own children as revenge against Jason’s infidelity; and that he invented her escape from retribution by having her fly off in her grandfather’s supernatural chariot. What is more, the final scene of Euripides’ play is made around the superior power of Medea, above and out of reach, over Jason who protests helplessly below. This “spatial dynamic” surely lends stronger power to the composition of this painting. There are also undeniably differences between the painting and the play – above all the children are in the chariot with Medea in the Euripide’s – but these are far outweighed by the associations. The painting does not “need” the play, but it is enriched in meaning for those who have seen this particular story in performance.

I would say the same of this vase of c. 360 (fig. 4), showing Iphigenia as a priestess, and her brother Orestes, as yet not identified as such, sitting on the altar awaiting his execution as a sacrifice to Taurian Artemis.

This whole story was the invention of Euripides; and the vase will mean much more for someone who know his play Iphigenia among the Taurians. You may have been struck by the similarity between this composition and that by the same artist on the crater with the scene of Neoptolemos at Delphi (fig. 5). But in this case it is a matter of hearing rather than seeing the Euripidean tragic version. So far as we know, it was Euripides in his Andromache who first brought Orestes into the story of the death of Neoptolemos. The messenger in that play tells how Orestes organised a cowardly ambush of the unsuspecting Neoptolemos while he was consulting the oracle at Delphi. The painting makes sense without the play, but it is that particular version that gives fuller significance to the participation of Orestes and the way that he is lurking behind the omphalos-stone. This is on a vessel known as a volute-krater (a wine-mixing bowl with volute handles at the top). This became a favourite shape for the Apulian mythological vases, and as the fourth century went on they became larger and larger (this one is 57 cms. high), and more ornately painted, with increasing use of white, yellow and purple paint.

This type of monumental potting and painting reached its peak in the third quarter of the fourth-century; and its master was the prolific and inventive artist who is known as the “Darius Painter”. Here is a typical example of his work, standing over a meter high (fig. 6).

As in the messenger speech of Euripides’ famous play, Hippolytos, the young man tries to control his horses which are being maddened by the supernatural bull that is appearing before them. There are two of the signals that are common in the tragedy-related pictures. One is the bent old man to the left: he is the recurrent figure of the male carer (in Greek paidagogos); and earlier in Euripides’ play he had tried in vain to warn Hippolytos against his arrogant attitude towards the goddess Aphrodite. Secondly there is the “frieze” of divinities above: it is a notable standard feature that they are calmly detached from the terrible human tragedy that is being enacted below.

This vase, like those related to Andromache and Iphigenia in Tauris, came originally from Apulia. So does this painting of the farewell of Alkestis (fig. 7), another celebrated Euripidean hit (note the paidagogos figure again). Likewise this picture of Prometheus bound to a kind of stage-rock, (fig. 8) probably alluding to Prometheus Unbound, a now lost play of Aeschylus. There was also a local school of painters in Poseidonia/Paestum, which also shows awareness of tragedy. The area of vase-painting with least artistic quality, and least direct relation to theatre, was probably that from Campania, the largely Italian hinterland of the Bay of Naples, dominated by Capua. But there are some items of interest from there, for example this relatively small vessel showing Orestes attacking his mother Klytaimestra (fig. 9). In addition to the snake-bearing Fury (or Erinys) in the upper right, a signal of the mother’s curses that will pursue Orestes, as in the Aeschylus, notice the way that Klytaimestra is holding out her exposed breast. In Aeschylus’ play Choephori, she tries (in vain) to stop Orestes from killing her by appealing to “this breast” where he had fed as a baby. Again, the picture means more to someone who knows the tragedy.

In many ways, the most interesting area of production of Greek pottery painting in relation to the tragedy is Sicily. The Sicilian mythological paintings are often closer to the practicalities of the theatre, revealing and exploiting an awareness of the link with a particular tragedy. This is especially the case with paintings from the second half of the fourth century, but consider this fine crater dating from about 380 (fig. 10).

It shows the scene of Amphion and Zethus, the sons of Antiope, about to kill the tyrant Creon, while a wild bull drags the body of the cruel queen Dirce away to the left. We have this very scene in a papyrus of Euripides’ play Antiope, and so we know that he revealed the assassination tableau on the wheeled trolley, the ekkyklema, and that it was interrupted by Hermes ex machina. The composition of the painting seems to reflect these stage devices. Next, this scene (fig. 11), by the same painter, excavated at the Fusco necropolis in 1915, also delineates a cave-mouth, this time the dwelling of the marooned Philoctetes on Lemnos. While this is probably related to a tragedy, it is not the Philoctetes of Sophocles.

As I said, some later Sicilian vases are more consciously and explicitly reminiscent of the theatre. This one, for example, form Lipari (fig. 12), shows the violent scene being enacted in front of painted pillars like theatre scene-background. We cannot relate this to a particular tragedy, nor can we this, (fig. 13), excavated at Capodarso, and dating to about 330. As you see the four figures are actually standing on a small stage – something found on many comic vases, but nowhere else so explicitly on a vase related to tragedy. This is probably not a realistic picture of a stage, and may well not be an actual moment from a tragedy, but the invitation to think of the theatre and to recall a particular play is exceptionally clear.

Lastly, the most important of all for present concerns, this fragmentary calyx-crater of c. 330s BCE, by the same painter, and excavated at Siracusa in 1969 (fig. 14). This has indications of a stage-setting through the pillars and the stage beneath the characters’ feet. And this time the play is not unknown. It is almost universally agreed, and rightly in my opinion, that this evokes a particular scene from Sophocles’ Oedipus the King. The old shepherd from Corinth is telling Oedipus how he received him as a baby on Mount Cithaeron, and took him to king Polybus at Corinth. Oedipus is puzzled, but Jocasta, to the right, raises her cloak to her face as she now first realises the truth. What is especially telling is that the painting captures a moment that is eye-catching in performance, but is not directly marked in the spoken text at the time. The appeal of the vase is directed, that is to say, at a viewer who has seen the play rather than one who has read it or only heard about it. It is ironic that Aristotle, who insists in his Poetics that one can experience the whole tragic effect of Oedipus without seeing the play, also singled out this particular performance-moment for praise (Poetics 1452a24).

It remains to be asked, finally, what was the function of these huge and highly worked ceramics; and what tragedy has to do with their context. It is beyond doubt that most, if not all, were produced for funerary occasions, for displaying as part of mourning, and for burying with the dead (which is why they have survived in tombs). So part of the explanation of the presence of tragedy in the pictures may well be that the dead person was a great devotee of the tragic theatre. But these distressing pictures of human conflict and disaster will hardly have been of any comfort to the mourners. Scholars have tended to clutch at redeeming features in the stories, ways in which some kind of reunion or happy ending can be salvaged from the tragic myth. But too many of the pictures show stories that are too grim, too horrific, too unreconciled for this somewhat sentimental kind of explanation to satisfy. What might there be about tragedy as a whole, in all its dark distressfulness, that might have supplied some kind of consolation for the grief of bereavement?

My thesis is that there is a kind of “aesthetic” comfort to be drawn from these paintings, a suggestion that human lives, for all their muddle and misery, leave behind traces that are “beautiful”. The stories of the myths are enacted by people who were grander and more splendid than us ordinary mortals, and they usually involve sufferings that are even worse, stokes of misfortune that are heavier, confusions that are deeper than those that we shall meet – at least if we are middling fortunate. And yet these stories are the stuff of poetry, and the stuff of paintings. What the vase-painters do is to take these stories of “the worst in life”, and turn them into pictures that have form and colour, poise and shapeliness. The painting becomes in itself a thing of beauty. It is not that the fourth-century paintings censor anything unpleasant. They still show grief and violence, wounds and corpses, but they are always portrayed in a way that retains a certain distancing calm. However ugly the story, the painting is never ugly. These paintings, seen within their context at funerals, draw out the human capacity to see form and colour even the worst as suffering, even in the bitterest depth of bereavement. And that is why these vases relate to tragedy, and not to something more ordinary, beguiling and comfortable. True comfort needs something beyond what is merely comfortable, if it is to go deep.

In experiencing tragedy in the theatre, people are taken to a prospect of the depths of horror, to crises of instability, and trials of endurance, such as we hope that we shall seldom, we hope never meet in reality. And then at the end of the play, no one is dead or traumatized. And this experience of the abyss, this journey into disorder has been seen and heard in a form that has beauty. The poetry, dance, music, the costumes and voices, the fluency of sound and action have all conspired to make the experience strengthening and not weakening. At the funeral the dead really are dead, nothing, no amount of grief will make them stand up again. And the dead person’s life will have included, like all our lives, its disappointments and deceits, its ugly episodes, its griefs and anguishes. What the magnificent and graceful ceramics do is to distil the beauty out of all this human muddle. The vase-paintings and the tragedies alike, the pots and the plays, interact to give us the renewed strength to live on without surrendering to the clutches of the dark.

English abstract

The article published here is the Italian translation of a lecture on vascular and theatrical representations given at the University of Catania on 18 January 2010 by Oliver Taplin. This essay focuses on the variable and non-continuous phenomenon of the representation and depiction of theatrical scenes. In particular, the period taken into consideration is the century from around 420 to 320 B.C. and the places are the Greek colonies in Sicily and southern Italy - Magna Graecia - and in particular Apulia.

keywords | Pots&Plays; Oliver Taplin; Paintings; Vases.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: A. Banfi (a cura di), Oliver Taplin, Raffigurazioni vascolari e rappresentazioni teatrali, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 78, marzo 2010, pp. 15-30 | PDF