The strength and beauty of other cultures

An appreciation of Aeschylus’ Le Supplici (Suppliants), Inda, Siracusa 2015, and an interview with director Moni Ovadia

Oliver Taplin

English abstract

I am extremely glad to have seen Aeschylus’ Le Supplici, directed by Moni Ovadia, at Siracusa in the summer of 2015. The production was both moving and entertaining, full of music and colour, yet tinged with a sense of danger and long-suffering. When I travelled to the ancient Greek theatre on 2nd June I had very little idea what to expect. The Aeschylean play is seldom performed, and for reasons that are not difficult to grasp: the plot is simple yet not well known; the play does not have the darkness or disaster that we usually associate with “the tragic”; the chorus are themselves the central character, and their singing takes up a large proportion of the play. I saw it presented as a ritualized exemplar of primitive tragedy at Epidauros in 1964 (with music by Xenakis), and as a study in murderous gender conflict in a Romanian production in 1997 (directed by Purcarete); but what did it offer to Sicily in 2015?

I was partly prepared by the sight of so many recently arrived migrants from Africa in the streets of Catania. And Le Supplici is indeed a story of migrants fleeing from oppression in Egypt and arriving in Greece, the land that claimed to be more enlightened. Also the potential dangers of their arrival pose a dilemma for their hosts in Argos. So the play has a very clear and urgent topicality in the summer of 2015. But, while this present crisis was obviously persistently there in the background – and was indeed made palpable by the presence of an invited group of migrants in the audience – it was not made obtrusive or dominant. Nor was the interpretation of the play primarily political or demographic.

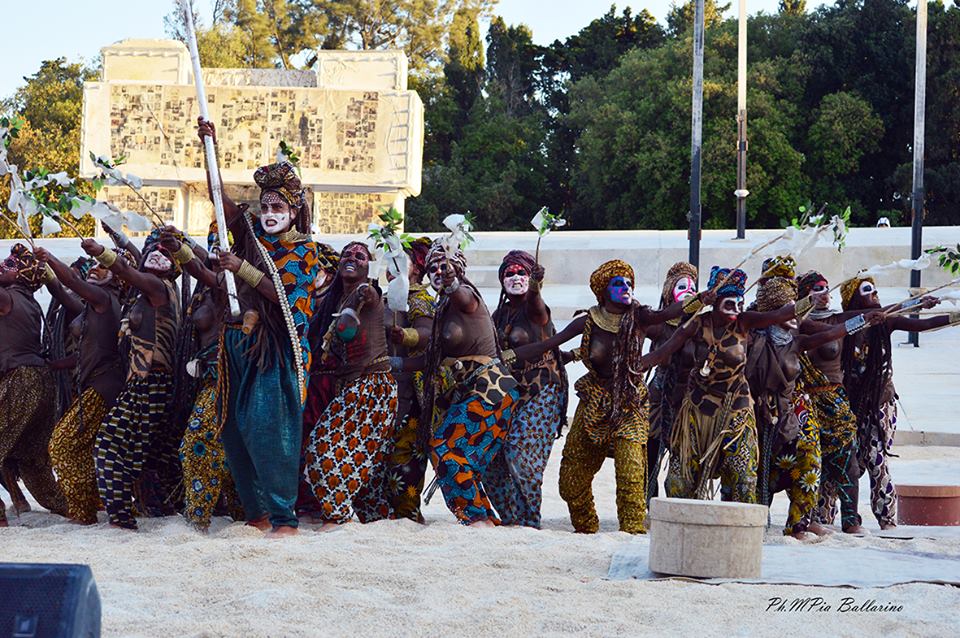

As I saw it, the primary drivers of Moni Ovadia’s production were not journalistic, but were ethnographic and musical. The centrality of the chorus was embraced. Through them Le Supplici showed how the arrival of foreign cultures from ancient lands bring fresh sights – clothing, utensils, gestures and movements. And above all they bring unfamiliar, often exotic, music and dance. These sights and sounds are novel, and yet traditional; the eyes and ears of the audience are opened to the strength and beauty of other cultures. This is not an easy burden to convey. It was achieved in this production by a superb control of group movement, beautifully exotic costumes, attractive choreography, and music that, although played on often unfamiliar instruments, was nonetheless tuneful and accessible. It was music that the audience felt it could have joined in.

It was in keeping with the strengths of Ovadia’s approach that the rather out-of-the way plot was not treated as a problem, or as something that needed academic explanation. Instead, the framing by the traditional Sicilian story-teller (who turned out to be Aeschylus himself: see the contribution by Mario Incudine and Pippo Kaballà in this issue of "Engramma") was skillfully interwoven with the large choreographed movements taking place in the action. And, again, music was the thread on which all was suspended.

To avoid appearing a completely uncritical “fan”, I shall now turn to the one area where I felt the production was less effective than it might have been: the threat of the pursuing Sons of Aegyptus. They are far from mere cardboard barbarians: they are out to impose enforced marriage – in effect institutionalized rape – on their cousins, the Daughters of Danaus. The language of the play portrays them as marauding dogs, crows, creeping spiders, vipers... Yet at Siracusa I found the Argive attendants of Pelasgus, who in their white protective suits looked rather like creeping maggots... I found them more scary than the rather melodramatically villainous Egyptians. Yet these are men who are out to violate the women of the chorus by force.

One problem was admittedly a constant physical feature of the Greek theatre at Siracusa: the outcrop of rock on the right-hand side, separated from the main acting area by a kind of “cliff”. The leader of the Egyptians proclaimed from here (as authority figures do there too often!); but this meant that, while he was given the power of height, he was physically cut off from his victims. So I believe that it would have been more in keeping with the whole dynamic of the production if there had been more stylized sexually threatening violence conveyed through the music and choreography.

Although I felt that this aspect of forced marriage was not sufficiently vivid, the production as a whole remained memorable – visually, musically, ethnographically. One of the most powerful deployments of the chorality of the ancient Greek theatre that I have ever had the good fortune to witness.

Interview with Moni Ovadia, director of Aeschylus’ Le Supplici (Suppliants), Siracusa 2015

Oliver Taplin How did you come to this little-known play in the first place?

Moni Ovadia To be honest, the staging of Aeschylus’ Suppliants was proposed to me by Maestro Walter Pagliaro, who is a very talented theatre director and had been recently elected as a member of the board of governors of the Inda Foundation. I had read Suppliants over forty years ago and my memory of the tragedy was extremely vague but it was nevertheless enough to attract my spirit of adventure.

OT Did you at first find its unusual nature a deterrent or a positive challenge?

MO Well, I definitely found its unusual nature positively challenging and extremely fascinating. I am passionately fond of epic narration and representation. The idea of confronting myself with a collective leading character, as are the Danaids of the choir, has been exciting though demanding. The undertaking was chancy but I faced it enthusiastically.

OT How did you reach the kind of music you wanted? Were the actual musical instruments important?

MO The choice of the musical language and its style came naturally after the decision of performing the play in Sicilian and modern Greek. Traditional Sicilian poetry, its meters and its mood, and the art of the "cuntu" are deeply interconnected with the forms of Sicilian traditional music. The same intimate and original relationship between poetry and music characterizes the expressions of ancient and traditional theatre in the Greek culture and in general in the musical and narrative art of the whole Mediterranean area. As to the choice of the musical instruments it has been determined by two different requirements. First, the necessity of achieving a satisfying Mediterranean sound; and second because of budget shortage: in Sicilian "picciuli nun ci nn’è"! A group of seven-eight musicians with some typical instruments – like the Kanoon, the Santouri or the Cretan lyre – would have been ideal. Nevertheless, our four outstanding virtuosos gave us an amazing and fully satisfactory sound.

OT What led you towards the kind of choreography that you developed?

MO We conceived our mise-en-scène as a musical opera or better yet a cantata. We strongly felt that each element in the staging had to be musically meaningful. When I arrived to Syracuse for the casting – I had to choose the majority of the actors and particularly the ones for the choir among the students of the INDA drama school – I decided to attend a dance lesson. At that moment I hadn’t yet made up my mind about who could be the choreographer for our Suppliants. From the very first moment I saw what the dance teacher, Maestro Dario la Ferla, was doing with his students, I remained struck by his extraordinary work with them and I remarked that even the silent movements he was asking the dancer to perform, expressed a strong musical fiber. It was love at first sight. I said to him: “Do you mind if I ask you to be our choreographer”. He accepted. Later he told me that he longed to propose himself for the role. I anticipated his longing. It worked out brilliantly.

OT How prominent did you intend the parallels with the sea-borne migrants from North Africa in summer 2015 to be, and how implicit rather than explicit?

MO We knew from the very beginning that our Suppliants had to be politically and socially relevant and especially connected with the dramatic problem of present immigration of people landing on our shores asking to be received. It was not only a demand of ourselves, the reality itself was asking it, Aeschylus himself keeps asking it from the depth of times, from the core of his tragedy. There was no need to show it explicity. The meaning of the presence of the sea-borne migrants among the audience is revealed at the very end of the play and has the purpose of declaring our commitment.

OT Did you feel that the Sicilian story-teller frame was indispensable?

MO Not indispensable but certainly necessary to express our conception of a theatre which goes beyond the rigid separation in genres. Functionally, the story-teller in the prologue allowed us to tell the story of the myth to the audience, explaining the origin of the plot of the tragedy, then to lead the audience through the untold parts of the plot itself and eventually in the epilogue to introduce the audience to the missing tragedies of the trilogy of which the Suppliants is part of. We did all this through the story-telling language which is musical, rhythmical and emotionally fascinating.

OT How valid – or how unjustified – do you find my criticism of the portrayal of the Sons of Egyptus as not representing the physical threat of sexual violence vividly enough?

MO It was Aeschylus’ text that led us in the depiction of the Sons of Aegyptus as we did in our staging. As far as I understood, they are thugs led by a Herald sent by the Egyptians to bring back their promised brides which ran away in order not to be forced to marry them. The task of the Herald and his soldiers is to capture the Danaids at all costs, even by brute force, but not to rape them.

OT What aspects of the production were you yourself most pleased with?

MO The whole work of directing the Suppliants has been marvelous in every respect. You have to consider this has been my first and for the time being my only direction of a Greek tragedy. But three aspects in particular I was pleased with the most. First, the magical collaboration with Mario Incudine - singer, story teller, composer, poet and legitimately co-director of the staging; second, the synergy of choreography and choral singing; and third, and most of all, the training with the choir of the Danaids. The highly professional commitment, the talent, the passion and the discipline of these still studying young actresses have been to me an unexpected gift. I experienced many strong emotions rehearsing and performing in theatres. But these young performers made me experience pure happiness.

OT Would you like to undertake another production of an ancient Greek play? Tragedy? Comedy?

MO Definitely yes, I would love to stage one more tragedy in the near future: Aeschylus’ Persians.

English abstract

In the first part of this contribution, Oliver Taplin presents Aeschylus’ Le Supplici directed by Moni Ovadia (Syracuse, 2015) as a visually, musically and ethnographically powerful version of the Greek tragedy.

The second part of the contribution consists of an interview with the director of the play on the reasons that led him to make some directorial decisions, such as musical and choreographic choices.

keywords | Syracuse; Inda; Le supplici, Moni Ovadia; Music; Choreography.

Per citare questo articolo: The strength and beauty of other cultures, O. Taplin e M. Ovadia, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 128, luglio/agosto 2015, pp. 53-59 | PDF dell’articolo