Further thoughts on Moise da Castellazzo and the Copyright Privileges granted to him*

Elizabeth Rich

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to introduce or re-introduce you to the Jewish artist known as Moise da Castellazzo and the images that he created in collaboration with members of his family in the early sixteenth century. It is a particularly appropriate topic for the recognition of the 500th anniversary of the establishment of the Ghetto of Venice, given that Moise was an artist living and working in the Venetian Ghetto nearly 500 years ago.

Moise was known as a painter of portraits, a medal maker, a designer of prints and an operator of a loan bank. Although none of this work survives, what does survive is a collection of documents housed in state archives. In fact, we know more about the life of Moise from his own hand and from the correspondence of others, including letters, court documents and documented privileges by noble families kept in the archives of Milan, Mantua and Venice. Professor Paul Kaplan of SUNY Purchase is one of the few scholars who has conducted research on Moise. In his essay –Jewish Artists and Images of Black Africans in Renaissance Venice– he provides a comprehensive summary of the known documentary sources, some of which I have summarized here (Kaplan 2005, 69-72):

1501 | Moise was a topic in several letters exchanged between the Venetian humanist, poet and Cardinal, Pietro Bembo, and his lover Maria Savorgnan – referencing several times a Jewish artist named Moise. “Moise has gone to Ferrara to make a medal of the duke.” Moise himself writes to Bembo to ask him what letters he wants on his medal and will make it at the same time as the duke’s”

1515 | There is a document showing the Duke of Milan granting tax exemption to Moise and his family, allowance to live and travel anywhere in the Duchy at the time and permission to carry any sort of weapon.

1519 | In Mantua, Marquis Federico II of the Gonzaga family grants Moise and his sons banking privileges and safe passage without having to wear the sign “which distinguishes Jews from Christians.”

1521 | Also in Mantua, dated May 17, 1521, there exists a document showing the Marquis of Mantua granting copyright permission for a set of biblical illustrations.

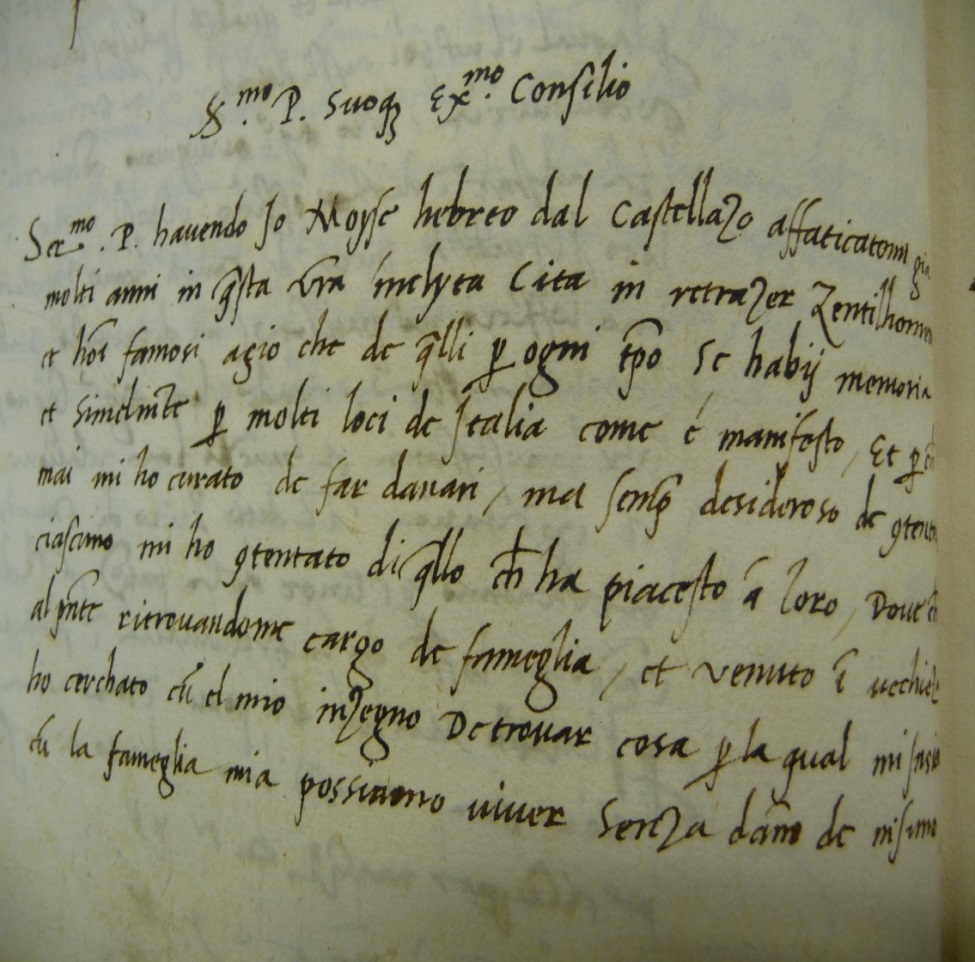

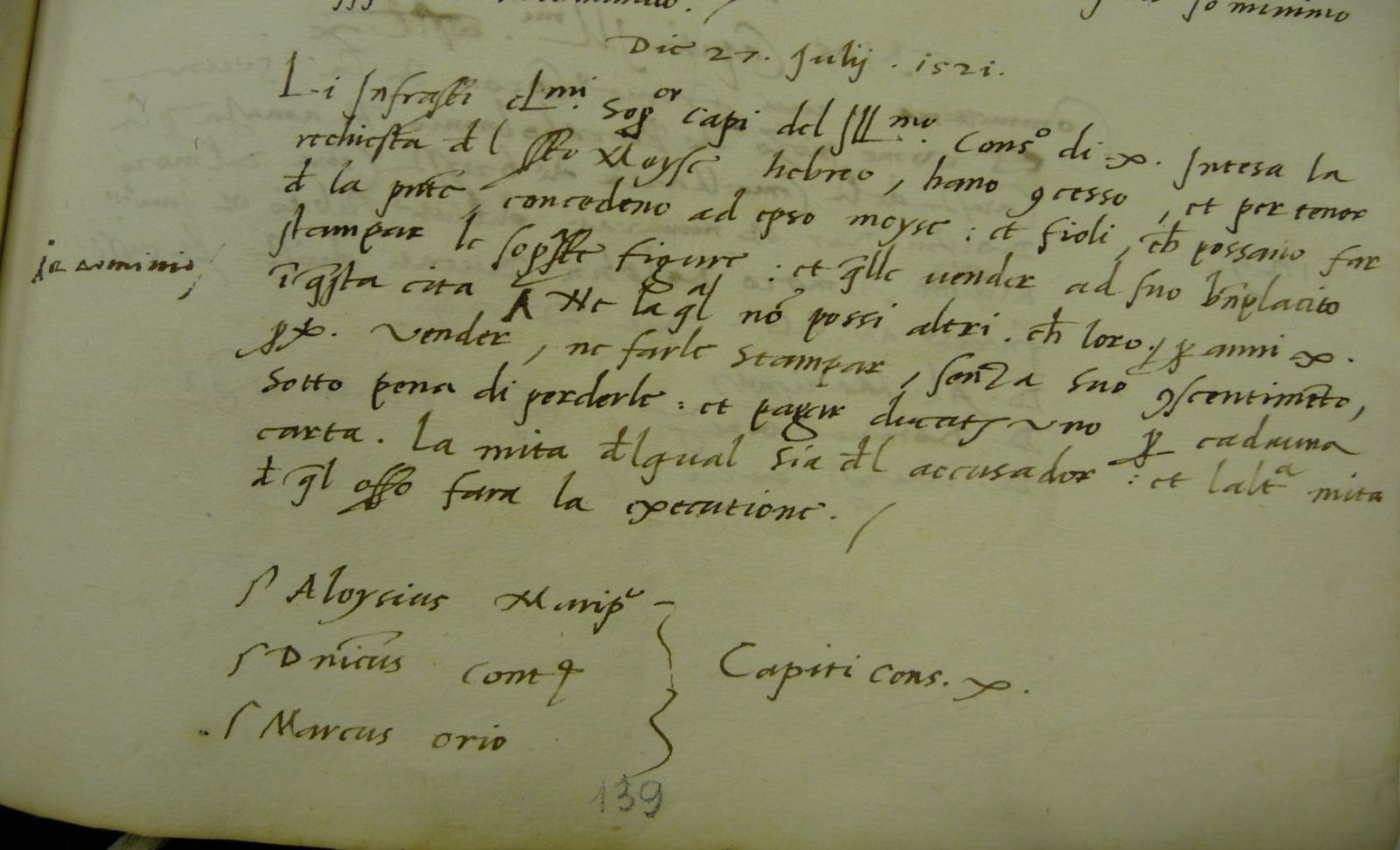

And in Venice, on July 27, 1521, the Council of Ten granted copyright permission for a set of biblical illustrations in response to a request submitted by Moise. This correspondence tells us a lot about Moise: his artistic accomplishments, his standing in society, his reasons for creating these images, and the planned layout of his book. It is worth a close examination. A copy of Moise’s request and the Council’s response can be found in the Archivio di Stato di Venezia (fig.1, fig.2).

fig.1 | ASVe, Capi del Consiglio De’ Diece, Notatorio no.5, fol. 121v-122r. Photograph ca. 2012 provided by the author.

fig.2 | ASVe, Capi del Consiglio De’ Diece, Notatorio no.5, fol. 122r. Photograph ca. 2012 provided by the author.

For purposes of my research I asked Dr. Corey O’Hara, Italian interpreter and translator, to provide an English translation of Moise’s request as well as the response from the Council of Ten. However, here first is the referenced letter in Italian:

Serenissimo Principe Suoque Excellentissimo Consilio.

Serenissimo Principe

havendo io, Moysè, hebreo dal Castelazo, affaticatomi già molti anni in questa vostra inclyta cità, in ritrazer zentilhomeni et homeni famosi, aziò che de quelli per ogni tempo se habij memoria, et similmente per molti loci de Italia, come è manifesto; et perchè mai mi ho curato de far danari, ma, sempre desideroso de contentar ciascuno, mi ho contentato de quello che ha piacesto a loro, dove che, al presente, ritrovandome cargo de fameglia et venuto in vechieza, ho cerchato cum el mio inzegno de trovar cosa per la qual mi insieme cum la fameglia mia possiamo viver senza danno de nisuno. La qual è questa che, in laude de missier Domenedio, io ho fatto intajar a mie fiole de sua mane tuti li cinque libri de Moysè, in figura; commenzando da principio del mondo, de capitolo in capitolo, dichiarati in più lingue la signification et il tempo de una etade a l’altra; et cusi faremo, piacendo a Dio, tutto il resto del Testamento vechio, ad intelligentia de tuti, cosa che sarà documento et a tuti molto fruttuosa. Et aziò che queste mie fatiche non vadano a male supplico, et dimando di gratia io Moysè soprascritto che li piaqui conceder a mi, et a mei fioli che possi far stampar et stampar ditte figure per anni X. In questa inclyta Cita de Venetia e terre et loci del suo Dominio et quelle vender et far vender. Et che nisuna altra persona de che sorte se sia ne I ditti lochi non possa stampar ne vender de tal sue figure ne simplice, ne in alcun libro nel sopraditto tempo sotto quella pena parera a la Vostra Serenita come per sua. Sollita Clementia ad altri inventori de coso degne per suo bon et natural instituto è sta sempre concesso alla gratia clementia e bonta de le qual Io minimo supplicante mi ricommando.

Die 27 Julii 1521

Li infrascritti domini superior Capi dell'Illustrissimo Consilio di X, intesa la richiesta del soprascritto Moysè hebreo, hanno concesso e per tenor de la presente concedono ad epso Moysè et fioli, che possano far stampar le soprascritte figure et quelle vender a suo beneplacito in questa cita et dominio, ne la qual non possi altri che loro, per anni X p.f. vender, ne farle stampare, senza suo consentimento, sotto pena di perderle e pagare ducati uno per cadauna carta; la mità del qual sia de l'acusador, et l'altra mità de quel officio farà la executione.

Ser Aloysius Marinero

Ser Dominicus Contareno } Capi Consilio X

Ser Marcus Orio1

Translated into English, the text of Moise’s request followed by that of the official document granting him the privilege of printing and selling the illustrations.

To the Most Serene Prince and His Most Excellent Council.

Most Serene Prince,

I, Moise, Jew of Castelazzo, having toiled for many years in this, your illustrious city, at making portraits of gentlemen and famous men, so that they may be remembered for all time, and similarly in many places in Italy, as is well known; and because I have never cared to make money, but, always desiring to make everyone happy, I have contented myself with whatever it pleased them to pay; such that at present, finding myself burdened with family and entering old age, I have sought through my ingenuity (or inventiveness) to find something to do by which, together with my family, we may be able to live without harm to anyone; and that is: in praise of the Lord God, I have had my daughters incise by their own hand all the five books of Moses in images, commencing from the beginning of the world, chapter by chapter, with the meaning and the time between one age and the next declared in several languages; and in this way, if it please God, we will do all the rest of the Old Testament, for everyone to understand, something that will be a document2 and of great benefit to all. And in order that my work may not be for naught, I beg and request that you please grant me, the above-named Moses, and my children, the right to print and have printed said images for ten years, in this illustrious city of Venice and the lands and places under your dominion, and to sell them and have them sold. And that no other person of any kind in these places may print or sell them, neither singly nor in a book, during said period, under whatever penalty Your Serenity should choose. The familiar mercy shown to other inventors of worthy things by your good and natural institution is always a concession to your gracious clemency and goodness, to which this humblest supplicant addresses himself.

July 27, 1521

The here-named Most Splendid Chief Lords of the Most Illustrious Council of Ten, having understood the request of the above-named Moisé, Jew, have conceded, and by means of this [document] concede, to this Moisé and children, that they may print the illustrations described above, and sell them at his consent in this city and dominion, in which for 10 years none other than they may sell nor print, without his consent, under penalty of their loss and payment of one ducat for each sheet, half of which shall go to the accuser and half of which shall pay the executors.

Ser Aloysius Maripetro

Ser Dominicus Contareno } Chiefs of the Council of Ten

Ser Marcus Orio

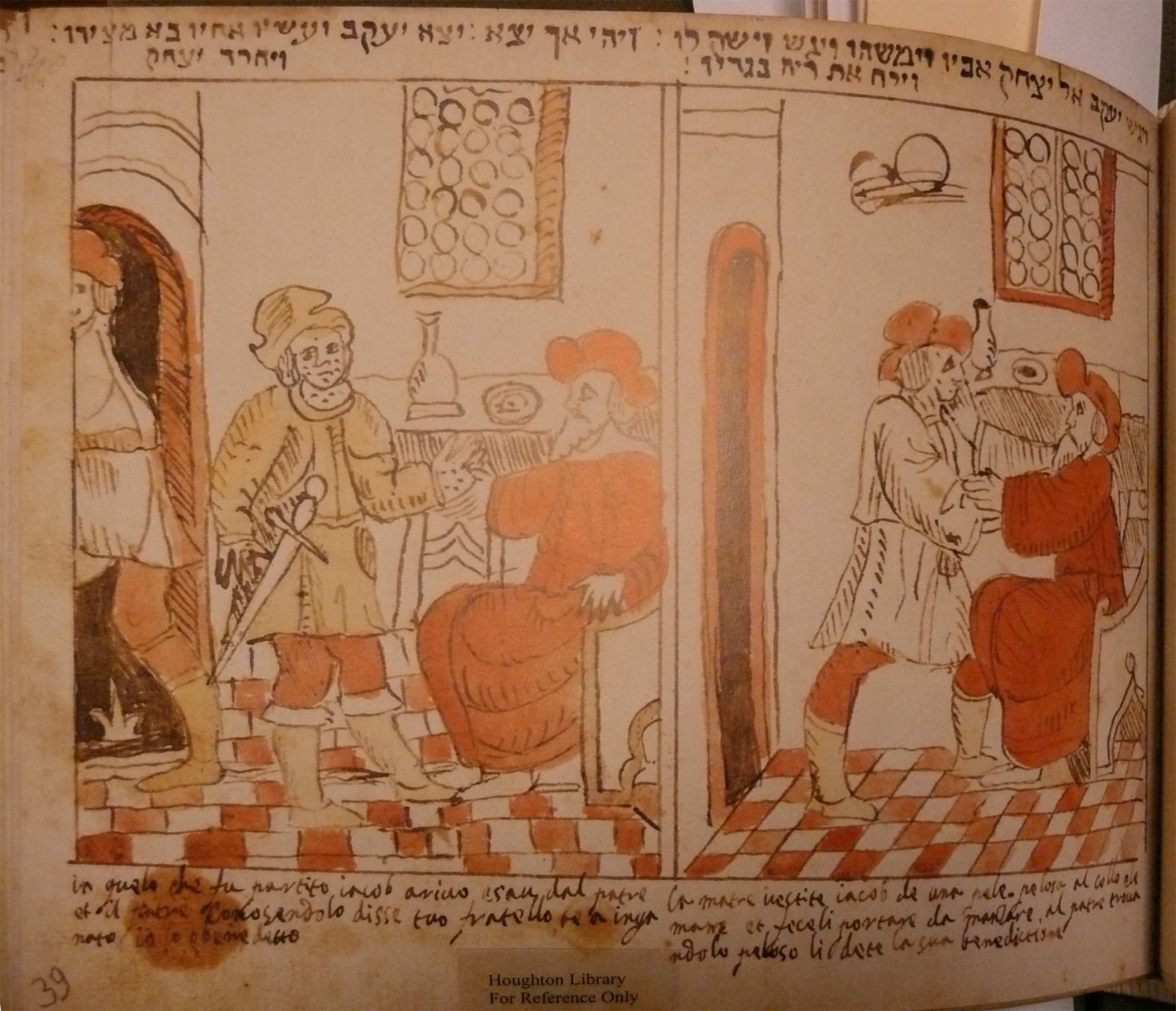

We learn precious information about the life of Moise from his request; he worked in Venice for many years of his life, he was a well-known artist in Venice as well as many other places in Italy, he portrayed noble men, and he created, with the help of his children, woodcut illustrations of the first five books of Moses –with future plans to complete the rest of the Old Testament. And if the wording of this letter is correct, as suspected by Paul Kaplan, Ursula Schubert and a few others mentioned in Kaplan’s essay, Moise included his daughters in this process by having them incise by their own hands the first five books of Moses in images. We also learn that the Council of Ten granted his request for copyright permission on July 27, 1521. These illustrations that received protection would have been a series of woodcuts, now lost or perhaps never printed. However what survives today is a series of watercolor drawings known as the Warsaw Codex 1164, believed to be copied from a woodcut series now lost, or perhaps a set of drawings used for the woodcut series (fig.3).

fig.3 | After Moise da Castellazzo, The Blessing of Jacob and Esau. Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw Codex 1164, fol. 39. Reproduction courtesy of Houghton Library.

The Warsaw Codex received its name because it was found in the basement of the Gestapo headquarters in Warsaw shortly after the Second World War. The late Kurt and Ursula Schubert of the University of Vienna are the scholars who contributed the most detailed research on Moise and the Warsaw Codex 1164, resulting in a 183-page commentary published in 1986, referred to as the Bilder-Pentateuch (Schubert 1983-1986). They make the case for its attribution to Moise and for a Jewish origin, for example the inclusion of Hebrew text above most images, and the fact that the images are viewed from right to left. Also, the Italian text in most cases connects to the rabbinical tradition.

To understand the significance of this letter and the privileges granted, we must look at what was happening in the world of copyright in Venice at this time. We can learn a great deal about this in Christopher L.C.E. Witcombe’s Copyright in the Renaissance (Witcombe 2004). On August 1, 1517, the Venetian Senate introduced a law revoking all earlier privileges and requiring new privileges to be approved by the Senate itself (whereas before this law they were granted through the College). This new law also required the vote of the full Senate with a two-thirds majority required for approval, and granted privileges “only to new works and to works that had not been printed before” (Witcombe 2004, 42).

Moise and his family were granted this copyright permission at a time when it was extremely difficult to obtain such privileges. From David W. Amram’s book, The Makers of Hebrew Books in Italy, we learn about printing in Venice a few years before Moise received this privilege. He writes:

The custom of obtaining privileges (copyright) had grown to such an extent that many printers finding no road open to their industry emigrated, to the great damage of public and private interests. The Senate therefore revoked every privilege granted and permitted any one to print any of the books mentioned in these privileges. And the law furthermore provided that in the future only new books, or books never before printed, […] could be protected by copyright and these only by a vote of two thirds of the Senate. (Amram 1963,158)

In Cecil Roth’s chapter on life in the Ghetto from his book Venice, he writes:

As a natural consequence, all of the protectionist theories of the period were enforced against them. Hence any attempt made by them to embark in any branch of industry was ruthlessly suppressed, an exception being made only in favor of entirely new activities which might benefit the State as a whole. (Roth 1930,172)

If only a new book or a new activity was approved, what was new about Moise’s picture-Bible and how might it be beneficial to the State as a whole? At the time that Moise and his family were creating these illustrations, he would have been familiar with the book market in Venice, including the market for woodcuts and engravings, making it an appealing time to create something for profit. In terms of the design of his book, he would have certainly known the rabbinical tradition of the Hebrew Bible. Moise came from a learned, and most likely wealthy, Jewish home. His father, Abraham Sachs, was a rabbi and banker (Kaplan 2005, 68). He might also have been familiar with Christian picture-Bibles of the time. Moise would have also been aware of the societal attitudes toward women working in business –most importantly in the creation of representational art in a religious context. This makes the inclusion of his daughters in the process all the more exceptional. Moise must have had all of this in mind when requesting the copyright privilege.

What stands out about Moise’s picture-Bible is the inclusion of two languages from the outset. The inclusion of two languages from the beginning, surrounding large images of human figures, is something unique. Bi-lingual and even tri-lingual psalters were quite common in the Middle ages, but entire bi-lingual bibles with images as the focal point were not. And Polyglot bibles contained side-by-side versions of the same text in several different languages but here the focus is on the text and not on the image. Religious images that are surrounded by text in more than one language was not a new concept. Many devotional texts were written in one language and later translated into other languages, but not created with two languages at inception. By including text in two languages, perhaps Moise was able to reach a larger Jewish audience –those who could read Hebrew and those who could read Venetian dialect. We could also assume that if Moise created his picture-Bible in two languages, he hoped that both Christians and Jews would be able to read his book, expanding his audience and making his document a great benefit for all.

The scholars who advocate Moise’s authorship of the images in the Warsaw Codex based themselves on some Jewish features of the images. Kurt Schubert provides more of this evidence when discussing the midrashic influence on 39 of the images. Midrash is the technique of interpreting or commenting on the Hebrew Scriptures and filling in gaps left in the biblical narrative –creating episodes that are not in the biblical text. Although Ursula Schubert points to a clear Jewish origin, she also compares the iconography of the images in Moise’s picture-Bible to Christian picture-Bibles. She suggests the Padua Bible and the Malermi Bible among others. Moise’s use of both Christian and Jewish elements, from Medieval to more contemporary religious books, speaks to his intention that his book was meant for an inclusive audience.3

Professor Katrin Kogman-Appel of the University of Munster is another scholar who wrote about Moise and his picture-Bible. In her paper titled Picture Bibles and the Re-written Bible, Professor Kogman-Appel determines that the particular literary genre that influenced Moise more than any other source was that of the “Re-written Bible”. She describes the term “Re-written Bible” as texts whose purpose was narration at single episodes or as entire books (Kogman-Appel 2006, 51-52).

It is clear that Moise had an inclusive audience (and possibly diverse too) in mind when creating and designing the images. He was also inclusive when involving his daughters in the artistic process. Some scholars believe his daughters worked on this project and some attribute the wording "mie fiole" to be a copying mistake (Kaplan 2005, 72). This raises the question, did Moise have in mind including females, literate and illiterate, middle-class and poor? Yes, I believe Moise would have wanted to expand his audience to as many people as possible, and that he was savvy and open minded enough to allow his daughters to work as the engravers or designers of these images. Certainly this is a topic that continues to deserve more attention.

Moise took creative liberties with his woodcut images; he added two languages to reach a larger audience, and he included human figures in a religious text in a way that was new. And perhaps he meant to include an audience that could not read. He also included Midrashic sources, as well as took inspiration from the literary genre of the “re-written bible”, perhaps to appeal to a Jewish audience who would appreciate sources outside of the traditional rabbinic texts or to demonstrate his understanding of the same. And his inclusion of Christian elements would help to target a Christian audience and perhaps add to his financial profits.

Although none of his works survive, it is amazing to consider what we know from archived correspondence between this artist and the governing body. We learn that Moise da Castellazzo was a Jewish artist who was granted special privileges from noble families, including copyright protection, and a smart businessman who wanted to capitalize on and protect his invention. And thus we know that he was a talented and enterprising artist who was able to cross religious, cultural, gender and socioeconomic boundaries of his time.

Notes

*A similar version of this paper, titled Moise da Castellazzo, the Consiglio dei Dieci and copyright privileges; How a Jewish artist protected his creation of a picture-Bible in 1521, was read on May 6, 2016 at the conference “…li giudei debbano abitar unidi…”The Birth and Evolution of the Venetian Ghetto (1516-1797), held in the Sala del Piovego, Palazzo Ducale, Venice, 5th & 6th May 2016.

1 This letter appears in Fulin 1882, 196-197, no. 226 (ASVe, Capi del Consiglio X, Notatorio, n. 5, c. 121v-122r). See Kaplan 2005, 72.

2 According to Dr. O’Hara, in this case “document” implies history, not simply a piece of paper. He is implying that this will be of use to everyone for ages to come.

3 I would like to thank Dr. Michela Andreatta for her expertise and advice on this and other topics in this article.

Bibliography

- Amram 1963

D. Amram, The Makers of Hebrew Books in Italy, London 1963. - De Hamel 2001

C. De Hamel, The Book: A History of the Bible, London 2001. - Fulin 1882

R. Fulin, Documenti per servire alla storia tipografia veneziana, in "Archivio Veneto" n. 23, 1882, pp. 84-212. - Kaplan 2005

P. Kaplan, Jewish Artists and Images of Black Africans in Renaissance Venice, in: Multicultural Europe and Cultural Exchange in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Ed. by James P. Helfers, Belgium: Brepols, 2005, pp. 67-90. - Kogman-Appel 2006

K. Kogman-Appel, Picture Bibles and the Re-written Bible: The Place of Moses dal Castellazzo in Early Modern Book History. “Ars Judaica” 2. Ed. by Bracha Yaniv, Ramat Gan 2006, pp. 35-52. - Roth 1930

C. Roth, Venice, Philadelphia 1930. - Schubert 1983 - 1986

Bilder-Pentateuch von Moise dal Castellazzo, Venedig 1521, Codex 1164, aus dem Judischen Historishcen Institut Warschau Facsimile Edition. 2 vols. Ed. by Kurt Schubert, Wien 1983 - 1986. - Witcombe 2004

C.L.C.E. Witcombe, Copyright in the Renaissance: prints and the privilegio in sixteenth-century Venice and Rome, Leiden-Boston 2004.

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to introduce or re-introduce you to the Jewish artist known as Moise da Castellazzo and the various privileges granted to him and members of his family by the Venetian government, as well as the noble families of Milan and Mantua. It is a particularly appropriate topic for the recognition of the 500th anniversary of the establishment of the Ghetto of Venice, given that Moise was an artist living and working in the Venetian Ghetto nearly 500 years ago.

By Moise’s own hand and from the correspondence of others living during his time, we know that he was a painter of portraits, a medal maker, a designer of prints, and a loan bank operator who lived in Venice during the early sixteenth century. Archival documents from Milan, Mantua and Venice provide evidence of the special privileges granted to Moise and his family. Some are quite extraordinary considering Moise was Jewish. This article focuses mainly on the request made by Moise to the Council of Ten in Venice. He asks the Council for ten years of copyright protection on a set of woodcut illustrations of the first five books of Moses, carved by the hands of his daughters. On July 27, 1521 the Council of Ten granted Moise and his family copyright protection.

Moise and his family were granted this copyright protection at a time when it was extremely difficult to obtain such privileges. Four years earlier, on August 1, 1517, the Venetian Senate introduced a new law granting privileges only to new works and only to those that benefit the State as a whole. This article will use Moise’s letter to the Council of Ten to demonstrate the ways in which Moise and his family set out to create a document that would meet the requirements of this new law.

We learn precious information about the life of Moise from his request; that he worked in Venice for many years of his life, that he was a well-known artist in Venice as well as many other places in Italy, who portrayed noble men, and that he created, with the help of his children, woodcut illustrations of the first five books of Moses, with future plans to complete the rest of the Old Testament. Unfortunately, none of Moise’s paintings or medals survive. What did survive, in addition to the archival documents, was a watercolor copy of a series of 211 woodcut illustrations from a picture-Bible created by Moise da Castellazzo and his family, known as the Warsaw Codex 1164. Although the original manuscript is missing, the study and interpretation of the images of the Warsaw Codex 1164, along with Moise’s letter to the Council of Ten in Venice, provides enough information to examine the ways in which Moise and his family created these woodcut illustrations to meet the legal requirements for copyright privileges of his time.

keywords | Venice; Copyright; Moise da Castellazzo; Ghetto; Venetian Jewish community; Manuscript.

Per citare questo articolo: Elizabeth Rich, Further thoughts on Moise da Castellazzo and the Copyright Privileges granted to him, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 136, giugno/luglio 2016, pp. 245-254. | PDF dell’articolo