Much of David Bowie’s gender bending and playing with sexuality has obviously been related to his sartorial changes and experimentation with hairstyles and makeup – traits that have marked him since well before his Ziggy Stardust career. Bowie’s changeableness with clothing and hairstyles, especially, have always marked him as seemingly feminine rather than masculine, his play with personae and frequent redirection in his musical tastes treated as metaphors for the same thing-fashion, not tailoring. That is, rather than appearing to be the staid unchanging authentic self, he seems to present a fluid pseudo-femininity that offers some kind of alternative. Pseudo-feminine because Bowie is not linked directly with the negative, perhaps misogynistic, aspects of female fashion as the reverse of masculine fashion – i.e., as throw-away culture meant to be replaced seasonally and to signify, at some level, frivolousness.

As Anne Hollander makes clear in Sex and Suits: The Evolution of Modern Dress, masculine and feminine fashion are not so easily divided – at least not until the ‘great renunciation’ of the nineteenth century, when the modern suit came into being, and really not after that (Hollander 1995). As she explains, women and men’s dress was originally much the same, with both wearing versions of drapery (the Greek chiton, for example). While men moved slowly toward shorter robes to allow for more physical movement, they were essentially wearing the same thing even in the early medieval period in Europe. All that was changed was the addition of leggings to account for the colder temperatures of Northern Europe over the Mediterranean. A gendered differentiation in clothes did not really appear until after the introduction of armor, and even then, the first iteration, chain mail, was essentially heavy drapery – i.e., the same costume made out of something else.

What we frequently think of as armor today – made of pounded metal and joints – was the beginning of male fashion. The different parts of a knight’s armor closely followed the contours of the male body and articulated a relationship between the body’s parts and the clothing over them that was not possible with drapery alone. Male clothing slowly evolved new elements – the pants, as we know them today, the shirt, the collar, the waistcoat, etc. Women’s clothes eventually adapted many of these ideas. The ultimate modernization of the suit of armor was the business suit, which maintains, to Hollander, the two essential elements of male clothing: that it reflect the male body and that it still act, to some extent, as a form of armor as well, insulating the body’s vulnerability and shielding the wearer, allowing him some distance and reserve, at the same time that he appears essentially nude.

For Hollander, then, the great generator of fashion innovation has always been male clothing. As Roland Barthes and others have pointed out, the male dandy has played an important role in the evolution of fashion: “Though slower and less radical than women’s fashion, men’s does none the less exhaust the variation in details, yet without, for many years, touching any aspect of the fundamental type of clothing: so Fashion, then, deprives dandyism of both its limits and its main source of inspiration – it really is Fashion that has killed dandyism” (Barthes [1993-1995] 2006, 69). In part this has come about by the seriousness accorded to anything male, especially in its connection to the public sphere, but also because women’s clothes essentially remained unchanged – a form of the classical gown – until women’s clothing began to take on male details and innovations. When absorbing male fashion traits, female dress still remained feminine – the male suit, even, finally making the female wearer seem even more like her sex or gender. But the invention was the result of male tailors. The only two truly female items of clothing, according to Hollander, were décolletage and the skirt, the latter as a separate piece from a gown. By the seventeenth century women also began to have not only bare necks but bare arms; the latter still not considered completely seemly for men, the former becoming popular in some situations as early as the late eighteenth century (the French Revolution, for example, or the myth of pirate clothing) and has reached its peak only now when casual wear is frequently open-necked.

Within Hollander’s schema, then, Bowie’s sartorial excesses can perhaps be more precisely mapped. For Hollander, men’s clothing in general, and the suit in particular, is much more multifaceted and changeable than people might imagine. The great renunciation, in which men seemed to turn over the fashion arm of clothing to women, was not quite what it seemed. Here and elsewhere, Hollander references the “Great Masculine Renunciation” outlined in J.C. Flügel’s The Psychology of Clothes, first published in 1930, Flügel’s famous thesis:

If, from the point of view of sex differences in clothes, women gained a great victory in the adoption of the principle of erotic exposure, men may be said to have suffered a great defeat in the sudden reduction of male sartorial decorativeness, which took place at the end of the eighteenth century. At about that time there occurred one of the most remarkable events in the whole history of dress, one under the influence of which were still living, one, moreover, which has attracted far less attention than it deserves: men gave up their right to all the brighter, gayer, more elaborate, and more varied forms of ornamentation, leaving these entirely to the use of women, and thereby making their own tailoring the most austere and ascetic of the arts. Sartorially, this event has surely the right to be considered as ‘The Great Masculine Renunciation.’ Man abandoned his claim to be considered beautiful. He henceforth aimed at being only useful. So far as clothes remained of importance to him, his utmost endeavours could lie only in the direction of being ‘correctly’ attired, not of being elegantly or elaborated attired. Hitherto man had vied with woman in the splendour of his garments, woman’s only prerogative lying in décolleté and other forms of erotic display of the actual body; henceforward, to the present day, woman was to enjoy the privilege of being the only possessor of beauty and magnificence, even in the purely sartorial sense (Flügel [1930] 1950, 110-111).

To Hollander, it was a codification of the neo-classical idea of the expression of the body through clothing. The minimalism of the suit, its abstractness and muted colors, can be read one of two ways: as an attempt to ape classical nude statues of the human male (or paintings that represent the same, such as the neo-classical work of French painter Jacques-Louis David), or as a sort of early modernism – an architectonic removal of anything unnecessary and distracting in order to create one overall effect. Bowie, in this sense, is already heir to fashion as a man enculturated as male. He must work against the codes that Hollander suggests. Throughout his career, one might argue, he has done precisely that. In his Ziggy costumes, he specifically bared his necks and limbs, giving his costumes a feminine nuance usually (but not always) a part of the look of the male suit, especially in the renunciation of the phallic tie, needed, according to Hollander, when the coat is buttoned and the crouch occluded. The addition of a décolletage has been a part of many of Bowie’s stage costumes, even when the more outrageous Ziggy costumes had long been retired.

According to Hollander, one thing that makes male clothing appear more classical and unchanging (positives to her) is the fact that men rarely mix codes – the suit is, by its very name, meant to worn as an ensemble made out of the same material. Bowie, in the late sixties and early seventies, confounded that expectation by purposefully wearing designs and bold colors that were much more likely in women’s clothing. He has periodically returned to this practice throughout his long career. What he has maintained from the land of masculine dress is some connection to the idea of the suit – to the unified silhouette and the overall effect – which he emphasizes with his use of one-piece outfits on stage. The effect, however, is again often subversively feminine. Bowie scrambles the codes of the body, the body’s expected clothing, and uses the costuming to add another dimension to his songs’ complex commentary on gender and sexuality.

While Hollander has less to say about hair than about clothing, she makes the point that long hair is often, depending upon the era, associated with male virility, though often in a free flowing, even slightly disheveled state. Women, too, can use long hair for sexuality, though it was, until recently, expected to be kept kempt. While hair length can, now, change for women and men, with short hair on women, like men’s suits, often emphasizing femininity, what men often do not have is elaborately styled hair. To complete his ensemble, Bowie has always maintained meticulous hairstyles. Whether the copper-top of the Ziggy period, which gets referenced again during his Earthling phase in the mid-nineties, to his slicked back Germanic look in the late seventies, Bowie’s hair style, color, texturing, even part, has always changed with each album, and even if it remains relatively fixed during an era, still undergoes metamorphoses. His hair, that is, like his dress, calls attention to itself in a specifically feminine way. The earliest television footage we have of him is as a member of the “Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Long-Haired Men” in which he sports long, straight sandy hair. His hairstyles changed as often as the cover bands he was in in the sixties, culminating with the long pre-Raphaelite hairdo of the Man Who Sold the World and Hunky Dory pre-Ziggy era. It was also at this time that Bowie wore dresses that he called “men’s dresses”. While he would go on to fracture gender codes more completely with Ziggy, producing a jagged, darker postmodern edge to his gender performance, in this immediately earlier period he was still not doing drag – not dressing as a transvestite – but dressing as a man wearing clothing that men (still) rarely adopt. He was forging his own approach to gender while calling attention to the scope and limits of how it is usually constructed by history and culture.

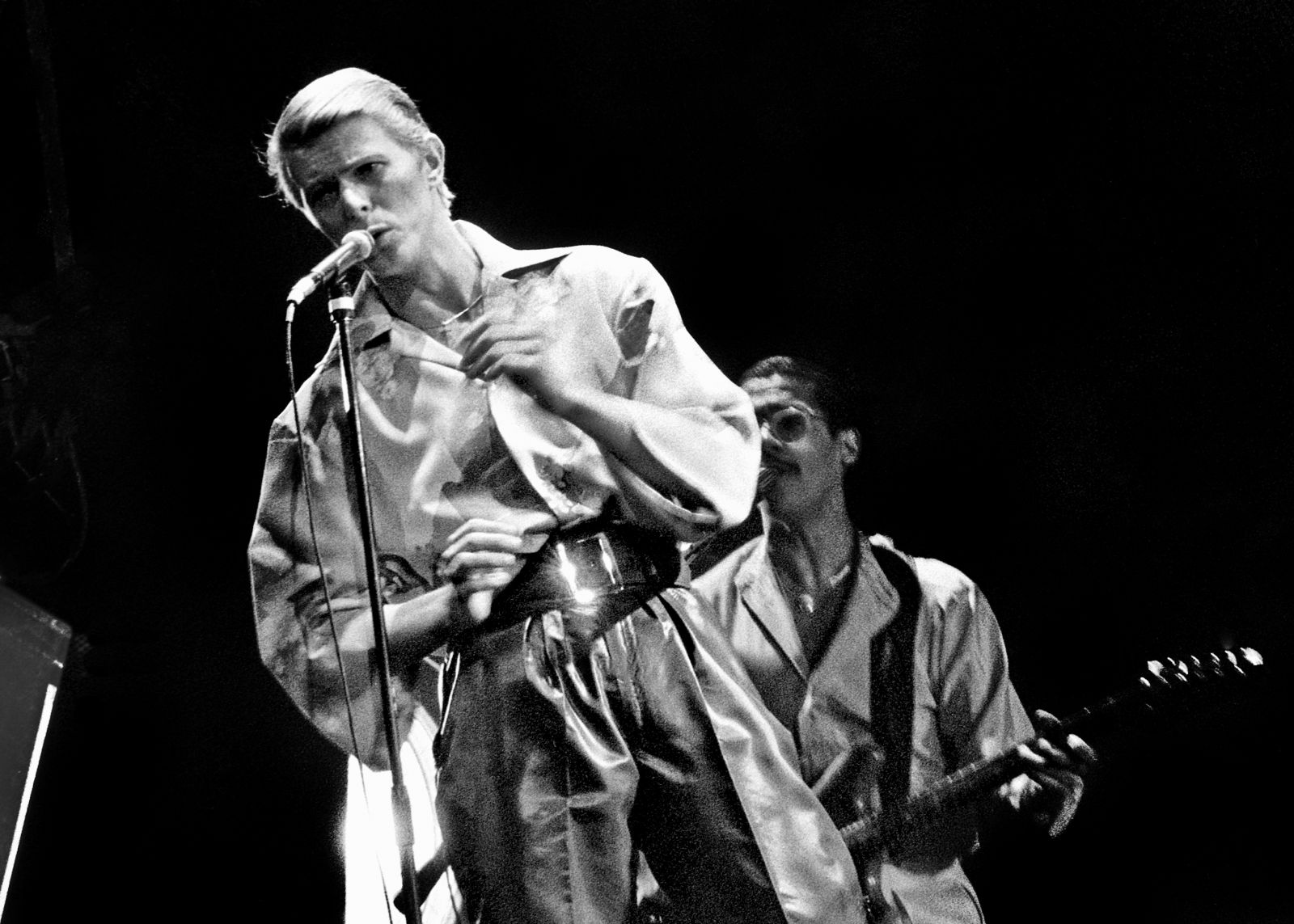

David Bowie, Isolar tour, Boston, 1976; Photo by John Adie Brundidge.

Bowie’s last major foray into gender and sexuality is perhaps his influence on Goth. While his album Scary Monsters introduced, or really reintroduces, the character of Pierrot, Bowie uses that figure as, to some extent, a Doppelganger for his own life as an artist, a made-up figure or clown. He also taps in to the notion of the playacting of gender – Pierrot is a strikingly feminine ‘white clown’ of the Commedia dell'arte tradition, made slightly futuristic and Asian in Natasha Korniloff’s version of the makeup for Bowie. Clearly, on the album cover and accompanying stills, Pierrot could be a man or a woman, a fact made clear on the cover where we see Bowie sans hat, smoking a cigarette in what looks like rumpled post-drag. While Bowie’s own subtle references to his gender bending past are made much of here, the album’s songs present a newer approach to gender and sexuality, ones that carry over from its immediate predecessor, Lodger. Scream Like a Baby references gay men hounded by police and the album’s first song, It’s No Game (No. 1) features female Japanese poet Michi Hirota in her own gender-bending performance. Bowie attempts to keep things real and connected to actual street-level politics.

While Scary Monsters and the Berlin trilogy before it may have influenced New Music or the New Romantics movement, the most important influence that Bowie had during that period on other musical styles may well have been Goth, or the Gothic movement. By the late seventies Bowie was being blamed by the media for spawning a variety of new styles of music, a claim that was intensified in the 1980s when Let’s Dance seemed at first to lay claim to another decade, whose sound Bowie was credited with having an undue influence over. The Goth sound, however, was one that Bowie seemed glad to claim, appearing with Susan Sarandon and Catherine Deneuve in Tony Scott’s 1983 film The Hunger as an aging vampire (John Blaylock). The film’s music, by Bauhaus, set the Goth template. Bauhaus had covered Bowie’s song Ziggy Stardust and the original song they sing here, Bela Lugosi’s Dead is a about an actor who plays a vampire in the presence of actual vampires (Bowie and Deneuve). The multiple levels of media references point to the elaborate number of jokes the film makes, but also to the extent to which Goth is itself an ekphrastic construction of art about other art.

That it gets its start in a film only to then become an actual movement parallels the origin of punk, which was also originally a joke, a fashion created by Malcolm McLaren’s boutique in London, that actually did tap in to a real movement of disaffected youth who identified with it and made the fantasy a reality – or saw their reality in its fantasy. In its references to Oscar Wilde, fin-de-siècle decadence, vampires, bisexuality, and sado-masochistic sexual practices, Goth became one of a number of counter-cultural pop music subcultures. Mainly a force in American high schools, it came to symbolize, like the subcultures before it, resistance to what Dick Hebdige calls the “parent culture”. What separates Goth from the fads that predate it is its emphasis on gender and sexuality.

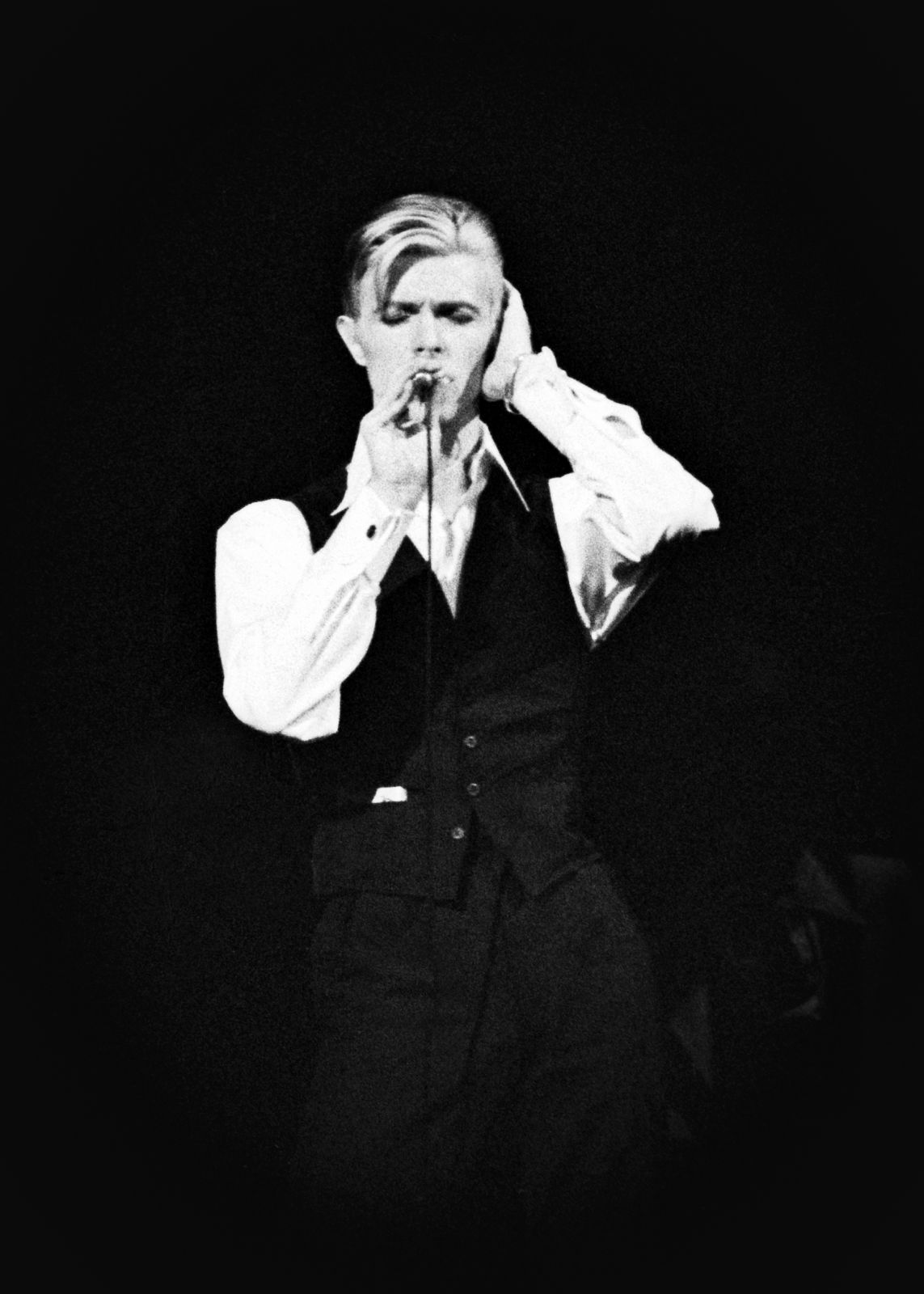

David Bowie, Isolar II tour, Boston, 1978; Photo by John Adie Brundidge.

That this understanding of gender and sexuality might be trite still does not take away from the fact that any alternative to mainstream versions of it may in fact provide young people with some source of resistance and some place for their identity to reside, however temporarily. In fact, by making connections between the late-Victorian period and the millennial period of the twentieth century, Goth was actually doing something critically to our sense of culture, making connections and offering a simulacrum for the present constructed of various fictions from the past – Bram Stoker, Romanticism, etc. One could also argue that Goth made this process self-conscious by quoting not people, but texts, images, and purposefully blurring the real with fantasy.

Bowie’s participation in the film, therefore, might have been, as Kimberley Jackson has argued, an attempt by Bowie to acknowledge Goth’s imitation of him, a deconstruction of his myth, and acknowledgment that the notion of his influence was about to change, that the notion of the rock star was about to be different and that Bowie was aware of the transformation (Jackson 2006, 186). Goth’s references to gender and sexuality were references to Bowie’s characters’ gender and sexuality, which became stand-ins for the real thing at the same time that they were acknowledged to be fictions or performances.

As Michael du Plessis argues, Goth references to gender and sexuality are finally not to gender or sexuality but to Goth itself. That is, “as a style, goth evokes depths of expression but, in actuality expresses nothing but itself” (du Plessis 2007, 162). Goth represents for him a type of melancholia, a loss that acknowledges the giving up of conventional gender and sexuality but that is so taken up with the signifying of that loss that it is finally all consuming: “Goth plays up melancholia, looping it through all manner of conventional gender performances in ways that always refer to goth’s own distinctiveness” (du Plessis 2007, 162).

In some ways Bowie’s participation in Goth in the early eighties signifies a sort of end point of gender and sexuality. He was, however, to return to Goth in 1995’s Outside, which presents a neo-Goth future in which the movement becomes, in a way, the defining mood for the end of the century again. While in The Hunger the vampires are bisexual, choosing a mate once every century, alternating male and female to avoid boredom, on Outside Goth is used not as a way to reference sexuality but as a way to suggest violence, especially the notion of the potential artistic side of ritualized murder. Goth takes a turn away from a fake darkness – Bela Lugosi’s dead – toward a real one, taken from the visual arts but also from the headlines.

The numerous references to Bowie’s play with gender and sexuality are too numerous to discuss in toto, but his attention to these topics shows a profound attempt to stick with the issue long after it may have had relevance to him personally. While he was not taking the notion of a gay identity or transvestitism literally, he opened the way for gender-queer performances and identities. Whether the pangender living performance of Genesis P-Orridge or the popularity of San Francisco’s porn and performance sensation Boychild, Bowie’s constant experimentation with gender and sexual alternatives and interrogation of what we mean by those concepts, has resulted in one of his most remarkable and misunderstood legacies. Bowie recodes the body for the future.

*An extract from the book: Shelton Waldrep, Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie, Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Bibliographic References

- Barthes [1993-1995] 2006

R. Barthes, The Language of Fashion, edited by A. Stafford, M. Carter, New York 2006. - Du Plessis 2007

M. Du Plessis, Goth Damage and Melancholia: Reflections on Posthuman Gothic Identities, in Goth: Undead Subculture, edited by L.M.E. Goodlad, M. Bibby, Durham 2007, 155-168. - Flügel [1930] 1950

J.C. Flügel, The Psychology of Clothes, London 1950. - Hollander 1995

A. Hollander, Sex and Suits: The Evolution of Modern Dress, New York 1995. - Jackson 2006

K. Jackson, Gothic Music and the Decadent Individual, in The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest, edited by I. Peddie, Farnham 2006, 177-188.

Musical and Cinematographic References

- Bauhaus, Bauhaus 1979-1983, Beggars Banquet, 1985.

- David Bowie, Hunky Dory, RCA, 1971.

- David Bowie, Let’s Dance, EMI, 1983.

- David Bowie, The Man Who Sold the World, Mercury, 1970.

- David Bowie, Outside, Arista/BMG, 1995.

- David Bowie, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, RCA Records, 1972.

- David Bowie, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), RCA Records, 1980.

- Tony Scott (dir.), The Hunger, cast: Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie and Susan Sarandon, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, USA 1983

English Abstract

Since the early 1970s, David Bowie’s name and identity have been synonymous with experiments in gender and sexuality – whether as the more conventional aesthete of the Hunky Dory period (1971) or the more outlandish gender-smashing deconstruction of the sexuality performance that would be inaugurated with Ziggy Stardust in 1972. While Bowie’s period in glam music is often taken to be a touchstone for a change in the attitude towards masculinity and male sexuality in rock music, little recent work has been done on just what the Ziggy phenomenon meant in terms of alternative genders and sexualities. This selection from the end of the first chapter of my book Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie attempts to think through some of the sartorial meanings that Bowie ignites and to make sense of them using the theoretical tools that have come about since that time. I hope to show that most of the vocabulary that we have for discussing Bowie’s representation of sex and gender are inadequate for describing what he was up to and that we may only recently have found accurate ways to discuss his performance, especially Bowie’s continued experimentation with alternative gender and sexuality coding beyond the Ziggy phase, most especially in his contributions to Goth. I bring my discussion of Bowie’s interests into dialogue with other music critics writing on Bowie and Goth, such as Kimberley Jackson, and with theorists of fashion, such as Anne Hollander and John Carl Flügel. Bowie’s contributions to the work of rock music cannot be understood without a necessary updating on his attempts to recode the body to create a pastiche of gender that ushers in not only the decade of the ‘70s but our thinking about gender and sexuality in the present as well.

keywords | Bowie; Gender; Fashion; Dandy; Goth; Clown; Melancholia; Identity.

Per citare questo articolo: S. Welderp, Body of Art. On David Bowie, Gender and Fashion, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 141, gennaio 2017, pp. 43-51 | PDF dell’articolo