It is difficult to find a picture of the major modernists – Corbusier, Gropius, Mies – laughing or even smiling. They mostly look stern, well-kempt, ‘authoritative’. Not so Ponti – windblown in his most popular late picture, but often actually playing with one of the objects he designed. And his work – like his many letters (of which a hundred have been published as a book) into which his humour seems to have overflown almost daily – that same good humour which pervaded all his activities – so that when you talked to him his latest project often seemed about the most amusing thing one could think of doing.

Not that he ever relaxed standards, as anyone working for or with him would know. He put you through a hoop or two before he gave you his confidence. Though once a collaborator was accepted their work was absorbed into the studio or some other enterprise even when it was individually credited. And he reasserted this generosity in his longest continuous text, Amate l’architettura (1957) in which the several partners with whom he had worked during all his career are all individually acknowledged. But his own development was marked by his personal, passionate commitment to both ideas and forms and the relations between them.

Always conscious of the way the world was moving, he was well-aware of the ‘rationalist’ modernism of his younger contemporaries in the Twenties – so that when his older and much more conventional contemporary Marcello Piacentini asked him to design the mathematics department in the new Rome University campus, his project was almost a declaration of adherence to their approach; it still stands out among its more commonplace neighbours. Yet he did not join any ideological group at the time. That he had a highly successful and productive career throughout the ‘Ventennio’, the twenty years of Fascist domination, without becoming embroiled in the ‘corporative’ organization of the profession is a tribute to his independence and integrity as well as to his diplomatic skill. In fact, his social and political beliefs were rudimentary and a little old fashioned: they go back to the programme Pope Leo XIII set out in 1891 in his encyclical Rerum Novarum which asserted the rights of workers to organize and act against employers but also maintained the legitimacy of private property and condemned political socialism - though I never heard him express these views or discuss them either publicly or privately.

Of those inter-war years, his most important single building was the administrative headquarters of the Montecatini chemical company in central Milan. Clad though it is in marble, it was a concrete-frame building with metal windows, an advanced heating and ventilation system as well as elaborate mechanical communication equipment. Though he was himself very fond of the rectoral building at the University of Padua where he also executed a large wall painting and where he could collaborate with a fine sculptor, Arturo Martini.

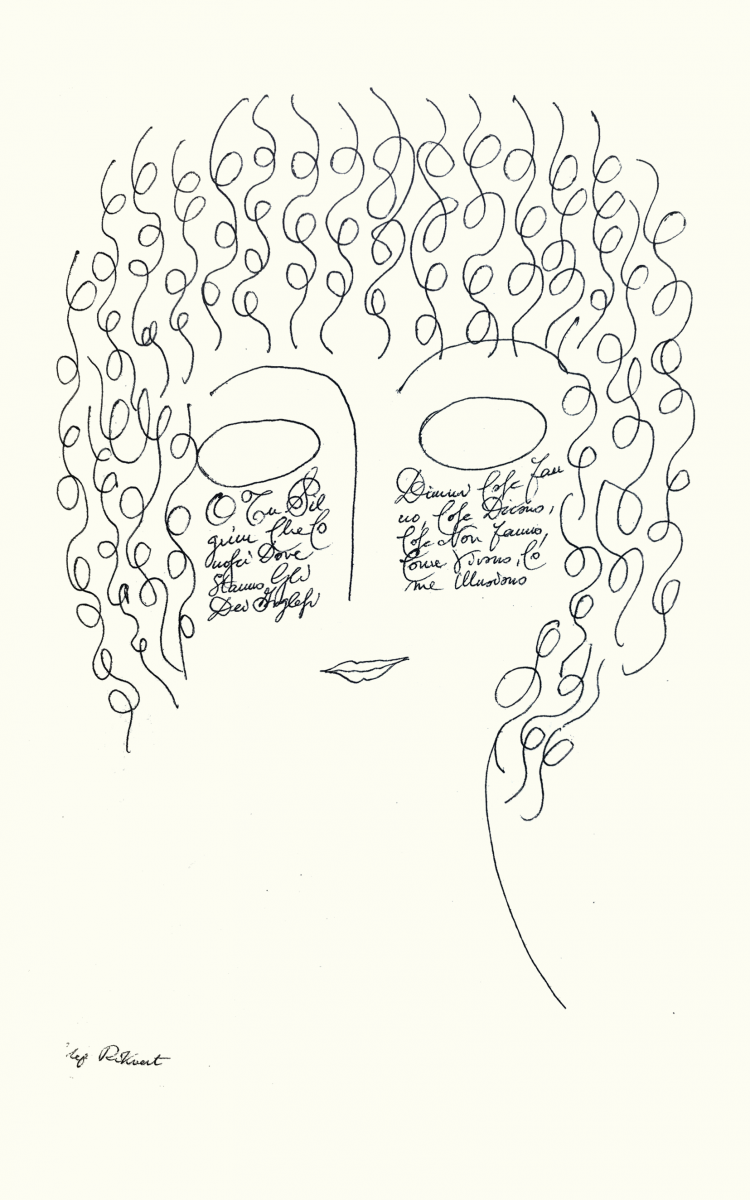

The wartime break in building saw him active as a theatre designer (the costume and sets for Strawinski’s Pulcinella provided one near-ideal subject for him), while the immediate post-war period witnessed the final flourish of the luxury transatlantic liner, whose mixture of discreet opulence with a spatial economy imposed by a ship-shape interior again provided him with an ideal field of activity.

His work as an industrial or theatre designer had always gone parallel with his architecture. His craftsmanly humility allowed him to collaborate with silversmiths or glass and porcelain craftsmen, joiners. Of the many strictly industrial products he designed, the many-nozzled Pavoni espresso machine would become one of his most prominent – but dear to him was the superleggera beechwood chair, which could be picked up by a child with one finger (and which is still in production).

Of his many post-war buildings, from Hong Kong to Caracas, the Pirelli Tower in Milan designed with four partners – its innovative structure worked out by Pier Luigi Nervi –is the biggest, and therefore most prominent and most discussed. Yet when we were looking at it together once, he observed censoriously that the proportion are wrong– it should have been two stories higher –nor would he accept any demurral on my part.

The review “Domus”, which he directed from its foundation in 1928 until his death in 1979 (with a wartime interruption) took its title from his early (and continuing) concern with the virtues of the Mediterranean house – that same domus which gave his review its title – whose advantages he wanted to perpetuate in the many storied twentieth-century city: hence his endeavour to extend it into a vertical extension without quite losing its virtues; it became an obsession to which his early block of flats – with their discreetly classicizing detail, the terraces and balconies – bear witness. But the title of the review is also a mark of his generous hospitality which indeed made the review such a successful forum of all that is most interesting in the design world of his time and which he was eager to welcome and celebrate.

His own dwelling was of course very much a domus – an open plan, a single floor high in a building he had himself designed, in which he loved to entertain friends and collaborators at lunch or dinner – hospitality was one of his true pleasures. The building also housed his office at ground level – providing the working space he wished for: an open space – like a hangar – in which drawings, prototypes and models were all being made at the same time – though he did have a cubby-hole into which he could withdraw – and from which those wonderful letters issued.

It was appropriate that one of the last buildings which engaged his inventive power in his closing years was a church – indeed a new cathedral – for the southern industrial port city of Taranto whose ancient-baroque basilica was too straight, too much of the ‘old town’. So, the authorities decided to build the new one on a free site, which has now been crowded in by mass-housing; the exterior of the concrete of the building neglected and graffitied.

The body of the church is a relatively low unified concrete hall, but its presence in the town is marked by two higher pierced belfry screens which are its modern equivalent of a campanile - the lower one at the entry, the much taller over the sanctuary and the two screens signals the church’s presence in the rather desolate environment of the deteriorating industrial harbour town. Nor was this an empty formal exercise for Ponti: the last (and longest) part of that book Amate l’architettura, which I mentioned earlier and which was written well before the Cathedral was designed, is a meditation on the nature of religious architecture in the twentieth (and so also twenty-first) century – which includes a generous homage to Corbusier’s pilgrimage chapel at Ronchamps, on whose intimately religious character he insists.

This long chapter asserts the need for a new religious architecture in the loneliness of modernity and makes evident Ponti’s personal commitment to thinking through the problem of such an architecture in our time:

... For the Church alone individual still exists... So, the wedding of the church with a man alone, that is what the architect should feel ever more urgent. That is the inspiration, according to which he should shape the House of the Lord proper for our time

and Taranto Cathedral is a clear proof of his personal commitment to this work and so the nearest that we have to Ponti’s spiritual testament.

Abstract

This text is a journey through a selection of ‘espressioni’ of Milanese architect, Gio Ponti. From his famous writings collected in the publication Amate l’Architettura, through the editorial achievements, stage-designs and the most famous architectures, such as the Grattacielo Pirelli, Liviano Rectorate Building of Padova and the Taranto Cathedral, without forgetting the most intimate one, his own domus, Joseph Rywkert walk us through a personal and kind portrait of his friend, Gio Ponti.

keywords | Gio Ponti, espressioni, architecture, potrait.

To cite this article: Joseph Rykwert, A memoir of Gio Ponti, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 175, September 2020, pp. 371-374 | PDF of the article