Cutting down the interpretation of drawings

The case of Watteau

Camilla Pietrabissa

English abstract

The notion of cut, compared to that of frame, implies that of a physical alteration. While framing indicates a cognitive operation, the cut refers to a material one. This essay interrogates the historical interaction between these operations, taking the historiography of landscape drawing as an example. For landscape drawing – a pleasurable practice taken up by artists since the 15th century – the notion of cut proves very productive to understand the parallel histories of mental and physical operations that gave rise to its minor position in the history of art. This minority is enhanced by the phenomenological nature of the genre, since in landscape images the margins of the work determine the mental process of selection of that portion of reality which is the matter of representation. In a phenomenological sense, landscape images always suggest the projection of the author’s paradoxical experience of creation. Paradoxical because, while free to create by inclusion, the author will necessarily cut out from the frame objects which were nevertheless potentially there. In the absence of a framing device, the mental cut of landscape drawings made from nature or from imagination is perceived by the viewer as a literal cut of the paper support. The history of material cuts in drawings, integrated in the theory of landscape imagery, can therefore be seen as a fundamental component of a historiography of representation. What follows is a first essay of a theory of landscape drawing, discussing the ‘material’ problem of grasping the ‘subject’ of such a representation.

A short history of cuts

The manipulation of drawings has always been a common practice in private collections and print rooms around the world. Unlike oil paintings, whose standard presentation framed and under protective glass primarily implies appreciation at a distance, drawings, and particularly Old Master drawings, require an additional kind of material study that requires close looking of the unframed work. In the quiet, secluded space of the print room, works on paper are presented in a cardboard mount to be picked up carefully and scrutinized on the surface and on the margins. Both sides are usually inspected. The drawing is thus apprehended via a number of elements such as inscriptions, additions in various media, framing devices, and collector’s marks, an array of traces of the complex history of the transit from the studio to the collector’s cabinet and the museum. The following pages are an attempt to interpret the evidence of cuts of the original paper support, resulting from three different types of operations: cuts performed along the margins, as in drawings that have been trimmed; cuts made at the centre of the sheet, as in the case of ‘splits’; finally cuts made by removing portions of the paper entirely, as in the ‘cut-outs’.The cuts analysed here occurred outside of the artist’s studio, at an unknown point in time, by a variety of figures such as dealers and collectors. Despite the paucity of information on the events that caused the cuts, they pose fascinating questions about the handling and interpretation of Old Master drawings. How can we recover what was lost in the process of cutting the margins of drawings? What alterations in the meaning of the work follow the physical ones? Any answer to these questions should consider the intersection of art history and the history of connoisseurship, as well as the history of restoration practices. Since the late 15th century, when drawings began to be exchanged, sold, and collected, they also began to be subjected to cuts (Karet 1998; Karet 2003, 29-37). As is well known, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) cut the drawings assembled in his Libro de’ Disegni, comprising between five and seven-hundred folio-sized sheets. The Libro, referenced repeatedly in the Vite, can be considered as a hermeneutical tool that worked as illustration of Vasari’s theories as well as a personal gallery to facilitate the study of artists’ maniere (Panofsky 1930; Kurz 1937-1938; Collobi Ragghianti 1974; Caliandro 1999).

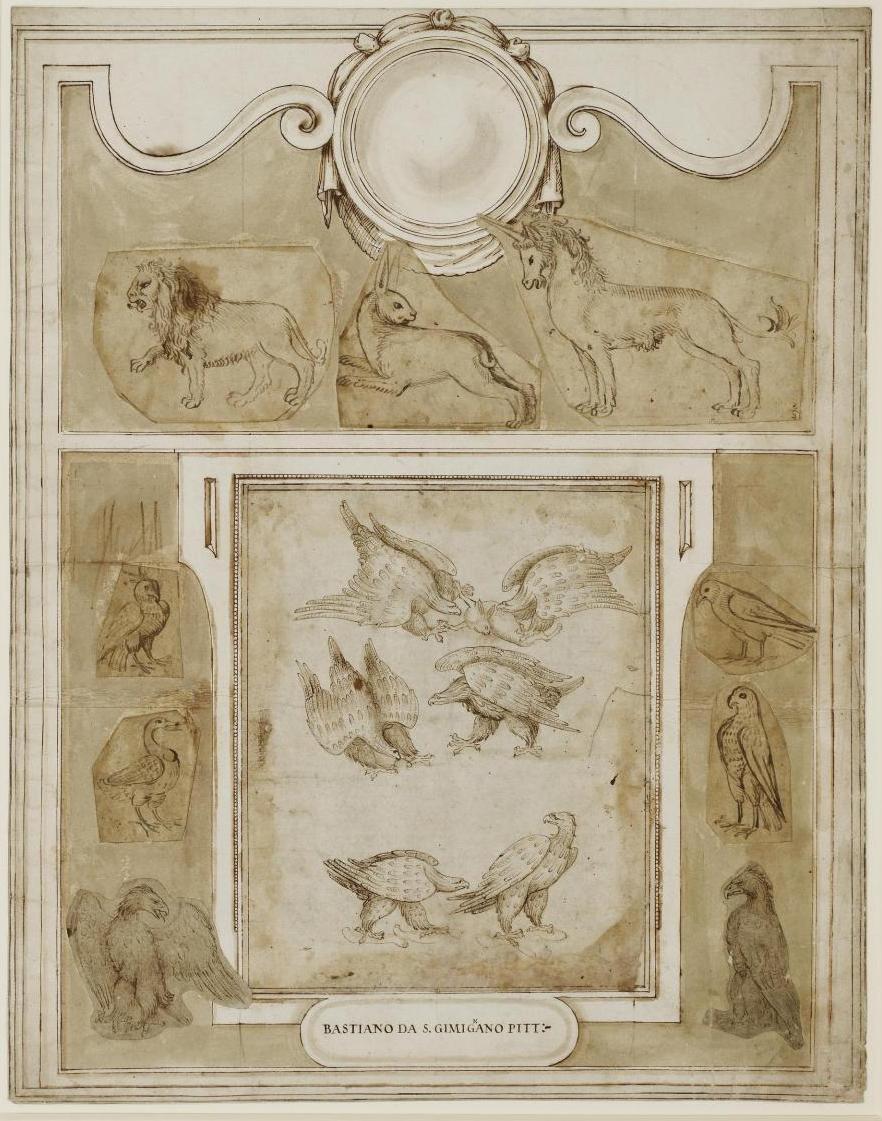

1 | Album page from Vasari’s Libro de’ disegni, with an arrangement of cut-out studies of animals attributed to Sebastiano di Bartolo Mainardi. Pen and brown ink, brown wash and red chalk, on ten sheets overlaid, 574 x 448 mm. The British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Despite the large format of the pages in the Libro – folio-sized, that is over 55 cm in height – drawings were cut to fit better into the ornamental, architectural frames in different polygon forms. The presentation of each page facilitated the comparison of works by the same author and the visual analysis of manner and techniques, but required many cuts and trimmings. In the case of a sheet from the British Museum, Vasari cut the figures along their margins to ease the attribution of studies of animals by Sebastiano di Bartolo Mainardi and other anonymous draughtsmen [Fig. 1] (see Degenhart and Schmitt 1968, 628-638; on this sheet, see Popham and Pouncey 1950, I, no. 153, II, pl. CXLIII). Vasari’s procedure facilitated the comparison of artworks in the same way in which finished works of art decorated 16th-century interiors (Monbeig-Goguel 1987; Forlani Tempesti 2012; Schenck 2013). The goal of such procedure was manifold, including enabling attribution proposal and training the eye to recognize period style and techniques. In short, the skills of a modern connoisseur.

By the early 18th century, practices of connoisseurship were transformed into a more universal analytical and rational method, derived from early modern empiricism and shared among a growing milieu of collectors and critics. Throughout Europe, visual expertise was practiced on a variety of things that were collected and displayed according to a methodical order, including, of course, natural history specimens (Pomian 1990; Bleichmar 2012).

In this context, drawing grew even more important in the theoretical discourse and drawings gained importance as independent works of art, as can be gauged from its primacy in the didactic system of the French Royal Academy of Art and Sculpture (Lajer-Burcharth and Rudy 2017, pp. 12-39). Subsequently, the burgeoning art market started producing a body of literature on the history of drawing in the form of sale catalogues.

From a theoretical point of view, moreover, the work of art was seen as the result of a process that could be reconstructed through a quasi-scientific analysis of graphic marks (Tordella 2012). Drawing was not the faithful evidence of the artist’s idea, as in Vasari’s texts, but rather the trace of artistic disposition or personal temperament. This attitude toward drawing can be considered as a symptom of a new anticlassical doctrine whereby the artistic gesture could enjoy an independent status – independent, that is, from its realization in painting or sculpture and more generally from commercial use (Griener 2010, 198). In terms of collecting practices this set of favourable circumstances meant that increasing attention was placed on drawings and their history. But dealers, collectors and theorists handled drawings in different ways, for different purposes: while the growing number of connoisseurs who promoted a new rational method for the study of art were concerned with the preservation of the original, others continued to manipulate and alter drawings for commercial or aesthetic reasons.

18th-century cuts

The case of drawings by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) fosters discussion about different types of cuts produced on drawings in the early-modern period and about the existing gap between the current principles of conservation and the informal cutting practices that occurred at various points in time.

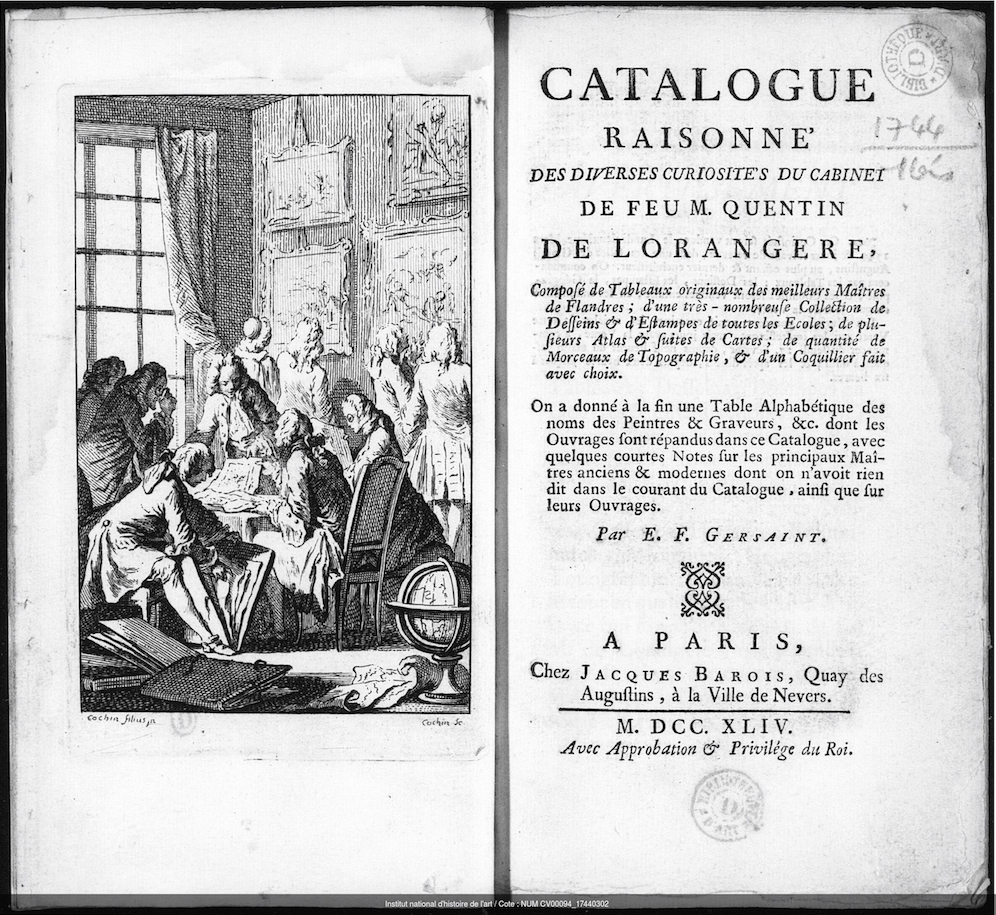

2 | C.-N. Cochin, Frontispiece to E. F. Gersaint’s catalogue of Lorangère collection sale, 1744, Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, collections Jacques Doucet.

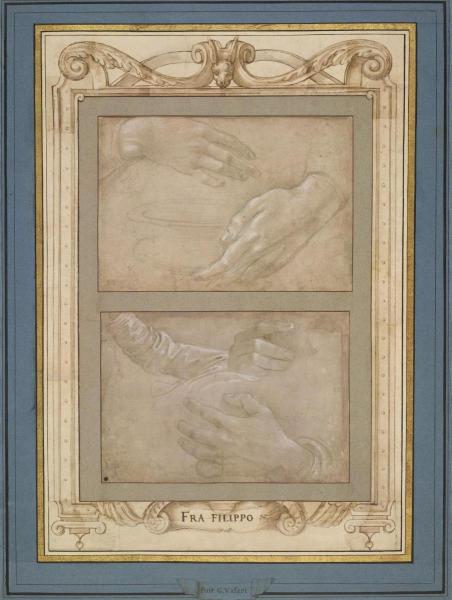

3 | Album page from Vasari’s Libro de’ disegni inserted in a Mariette mount, with studies of hands by Raffaellino del Garbo. Metalpoint, heightened with white on pink prepared paper, two sheets mounted together, sheets 145 x 210 mm each. The British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum.

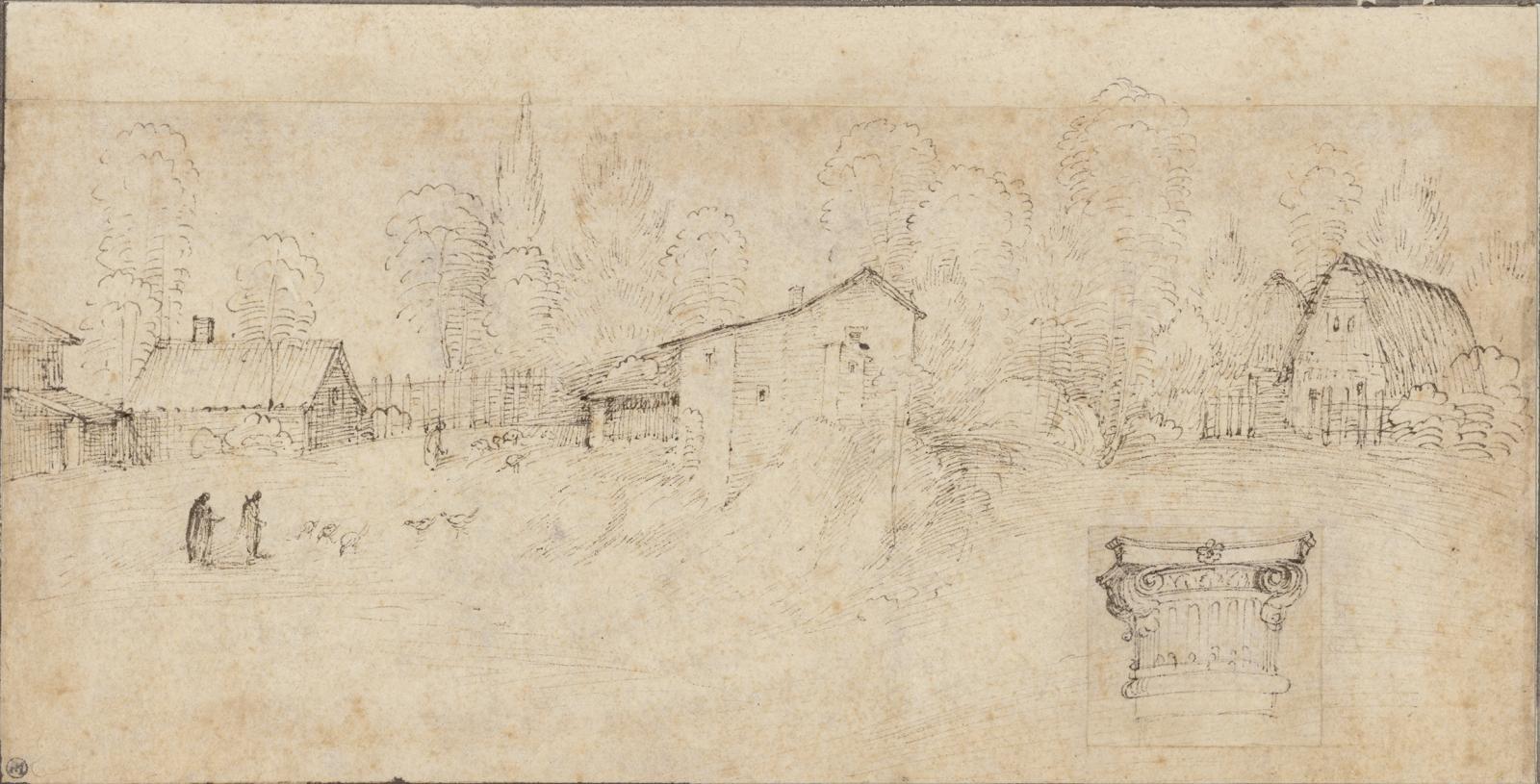

4 | Fra Bartolomeo, A sheet with paper additions, depicting a farmhouse and a capital from the Ospizio di Sta Maria Maddalena alle Caldine. Pen and ink, 107x210 mm. Albertina, Vienna. Photo © Albertina.

Watteau’s loose sheets, once bound in albums and praised throughout the 18th century, in Paris and internationally, were considered then as now as independent works of art. Nevertheless, as Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat have attested on various occasions, they have been subjected to alterations of all kinds (Rosenberg and Prat 1996, Introduction; Rosenberg and Prat 2011, 18).

Even if modern museums practices require that particular importance is given to the preservation of the material condition of the work, the interpretation biases originally caused by the cuts are perpetuated to this day. A trans-historical analysis of the treatment of Watteau’s drawings reveals the ways in which material cuts have affected their study in time.

In early 18th-century Paris it was not uncommon to cut drawings in order to frame them in mounts or to fit them into portfolios. Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774), the most famous connoisseur of his time, occasionally trimmed and split his drawings motivated by concerns about the impact of presentation on visibility (Smentek 2008). The method of scrutiny elaborated in Mariette’s milieu was based on the close observation and physical handling of the sheets (Smentek 2014, esp. chapter 2). In Charles-Nicolas Cochin’s frontispiece for the catalogue of the sale of the Lorangère collection (1744), the gentlemen gathered around the table handle sheets of paper with energetic gestures and scrutinize them with eyeglasses [Fig. 2]. This print suggests that a collection of works on paper was no longer enjoyed in isolation. The growing elite of 18th-century connoisseurs elaborated standard formats of presentation and conventional procedures to manipulate the sheets. Paradoxically, this implied that new alterations were made to ensure the best possible visibility.

As regards his own collection, which amounted to approximately 9400 sheets, Mariette was directly inspired by Vasari’s Libro for the design of the blue mounts with a golden band that are associated to him as well as for the cartouches and other ornaments that decorated them (Bjurström 2001; the history of the inspiration for Mariette’s mount is more complex, see Le Marois 1982). The main difference with the system of his predecessor lies in the fact that Mariette tried to make the drawings individually visible and handleable. A sheet in the British Museum that had originally come from the Libro shows Mariette’s determination to preserve Vasari’s mounting by incorporating the entirety of the original support into the mount, and by making restorations and enlargements that would help the beholder ‘see’ the work and its 16th-century arrangement in full (I. Rossi in Chapman and Faietti 2010, no. 47, 198-199) [Fig. 3].

As Kristel Smentek has demonstrated, Mariette’s concern with the possibility of seeing a sheet as clearly as possible prompted him to enlarge or, more rarely, cut, those sheets that could not fit the standard size of his mounts (Smentek 2008, 42-44). These alterations served to manage the visual experience of drawings, to present them at their visual best, so to enhance the viewer’s capacity to perceive an artist’s drawing manner. This paradoxical attempt to mediate the appearance of drawing by physically altering it exemplifies how the entry of drawings into the sphere of connoisseurial discourse affected not only its perception but its material existence too.

A landscape drawing by Fra Bartolomeo, once in Mariette’s collection and now in the Albertina, Vienna, serves to clarify this point [Fig. 4]. Chris Fischer has suggested convincingly that Mariette enlarged the sheet at the top with a tiny a strip of paper, an operation requiring the application of fine pen work to complete the uppermost part of the trees (Fischer 1989, 313-314). The detailed rendering of an Ionic capital in the lower right side of the sheet had also been glued in by Mariette, after removing it from another sheet with studies, to show that the site depicted was located in the area surrounding the Ospizio di Santa Maria Maddalena near Le Caldine, Fiesole, in whose loggia this capital could be seen. Although the insertion of a piece into the fibres that make up the paper is among the most radical of his interventions, Mariette’s manipulation is gentle and careful. In so doing, the connoisseur instructed future viewers on Fra Bartolomeo’s interest in topography, and particularly in the architecture of the convents, monasteries and villages around Florence. The resulting drawing can be read as a hermeneutical device with which the collector meant to enrich the understanding about the practice of an early Renaissance painter. Seen in this light, the kind of cut-and-paste procedure deployed by Mariette is more than a form of restoration: it is a fabrication of an entirely new object and an expansion of its meaning.

The afterlife of Watteau’s drawings

Watteau’s drawings were subject to a different kind of cut from those made by Mariette. Instead of a connoisseurial treatment, cuts on his drawings were mostly determined by current taste, that is, by factors relating to strategies of artistic reputation or the social value of pictorial genres. Watteau’s drawn oeuvre is calculated to have comprised between two and four thousand drawings, many of which were probably cut out from albums and split for sale (on the number of drawings see Rosenberg and Prat 1996, XII-XVI). Even so, at the time of the artist’s death the market for drawings by contemporary artists was not as developed as that for the Renaissance masters, and the wealthiest collectors did not buy the artist’s works (Bailey 1999-2000). Mariette’s severe assessment about Watteau was that he “handled drawing with finesse, but could never draw in the grand manner” (“ce peintre mettait de la finesse dans son dessin, sans avoir jamais pu dessiner de la grande manière” Mariette, Abecedario, vol. 5, 106).

Drawings by the artist were therefore put on the market in the decades following his death thanks to the efforts of his friends and supporters. Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766), an entrepreneur and collector who had been a good champion of Watteau, devised a successful marketing strategy for his drawings which included the publication of biographies and critical texts as well as the translation of his works into prints. Jullienne’s monumental project to translate Watteau’s drawings into engravings, titled Figures des différents caractères, de paysage & d’études dessinées d’après nature, was published in Paris in two in-folio volumes between 1726 and 1728 (Dacier and Vauflart 1921-1929). His supervision of a number of (mostly young) etchers for this project aimed to preserve certain characteristics of the artist’s draughtsmanship – virtuosity, energy and elegance (Tillerot 2011, 35). In the preface, the drawings are called “studies made too quickly to be completed” (“études faits avec trop de vitesse pour être terminées’ Jullienne, Figures, vol. 1, n.p.), an aspect of his artistic process that imparted the sheets with their most recognizable quality: their “natural and genuine character” (“un caractère si vrai et si naturel” Jullienne, Figures, vol. 1, n.p.). The selection of drawings and the organization of the volumes emphasized two features that gave the drawings the character of immediacy sought by collectors: Watteau’s tendency to multiply figure studies in the same page and his inclination to isolate motifs from their setting (Lajer-Burcharth 2015). Thus, despite the title’s claim that the volumes contained both figure and landscape studies, Jullienne gave greater priority to the former, including only fourteen landscape drawings over the total number of 272 plates. According to Marianne Roland Michel, the exclusion of many landscape drawings from the project could be explained by the fact that Jullienne “did not feel that they represented Watteau as the public expected him” (Roland Michel 1984, 158).

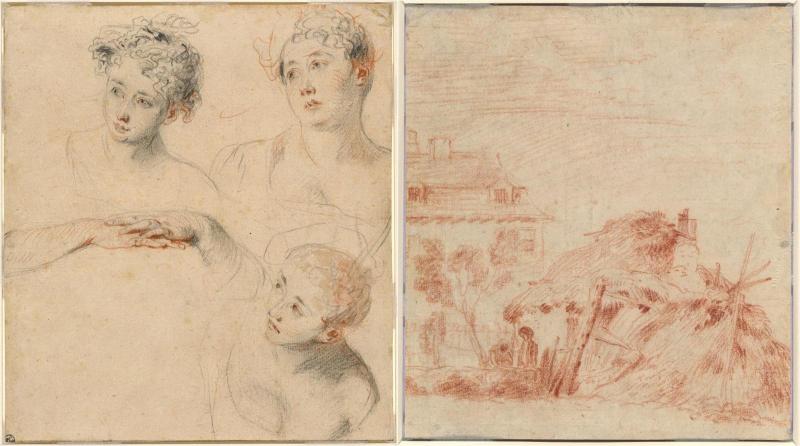

5-6 | J.-A. Watteau, Sheet with studies, Recto: Three studies of a woman’s head and a study of hands, Verso: Landscape study. Red chalk and graphite with black chalk and pink wash, 179 x 159 mm. The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

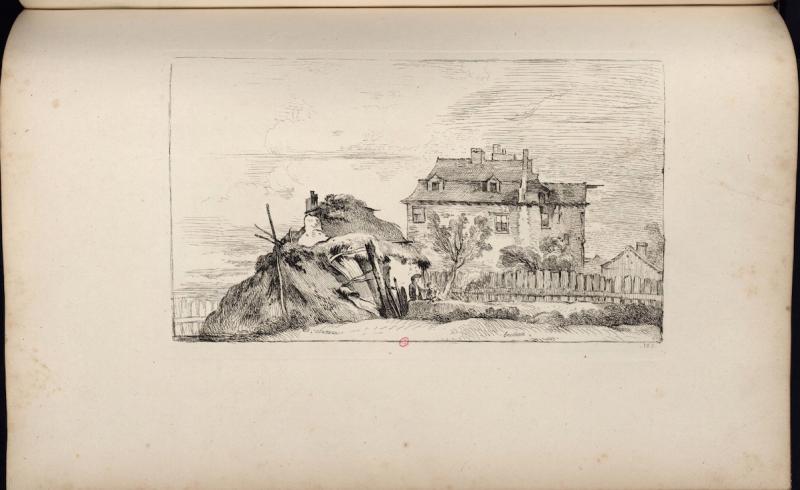

7 | F. Boucher after J.-A. Watteau, Plate 195 from Figures de différents caractères, depicting a rustic hut near a château. Etching. Paris, INHA, Collection Jacques Doucet.

More generally, Watteau’s interest in landscape drawing has been matter of debate, so that the attribution of many landscape sheets to the artist is still ongoing today (see for example the entry for a drawing in the Teylers Museum, Haarlem, in Rosenberg and Prat 2011, no. 10, 51). This is rather perplexing if one considers that Watteau’s 18th-century biographers claimed that his dedication to landscape had started early on, when he was an assistant to Claude III Audran at the Palais de Luxembourg and could stroll in the public gardens to sketch after nature (Jullienne, Figures, Preface).

This activity – according to the same authors – had continued in the area of the Porcherons where Watteau was a guest of Pierre Crozat (Mariette, Abecedario, vol. 5, 110; see also Eidelberg 1967). Later, his friendship with Jullienne would have brought him to draw the rural area around the Gobelins manufactory, as can be seen in the view of the Bièvre canal represented in Plate 23 in the Figures. Despite these accounts about Watteau’s interest in landscape representation, some scholars still regard Watteau’s landscape drawings as following compositional schemes typical of Italian and Flemish models, especially when compared with the immediacy and freshness of the figure studies (Michel 2008, p. 108). As a result, Watteau’s landscape drawings remain in a subordinate position with respect to the figures.

Consider a two-sided drawing in Washington, D.C. which has been cut into square format to improve the arrangement of the side on which Watteau has drawn three head studies, now disposed in three corners of the sheet [Fig. 5]. As a result of this cut, only slightly more than half of the landscape composition on the other side of the sheet is left intact, as we can gauge from an etching by François Boucher made in reverse for the Figures (Plate 195) [Fig. 6]. A quick comparison between print and drawing reveals that Boucher has been very faithful to the original, striving to render the details of Watteau’s composition and handling style [Fig. 7].

The fact that the sheet was cut after the production of the etching supports the argument that the Figures were an early, almost experimental project that created a market for Watteau’s drawings. Only at the moment of their dispersal, many drawings were cut according to aesthetic reasons at work in the commercial market. A further hypothesis on the reason for this alteration relates to the drawing’s function: a collector might have preferred to acquire the heads because they served as models for the girls depicted in La contredanse, a painting which is known today through old photographs and an engraving (Dacier and Vauflart 1921-1929, vol. 3, no. 177). The canon of taste that gives primacy to the human figure and the practical function of drawing in relation to painting is still predominant today in the assessment of Old Master drawings, at the disadvantage of sketches and studies without a direct use in painting (Rubin 1991). Thus, we might assume that many of the drawings have been cut to make for a nicer arrangement of the figurative elements especially if these were known in print or if they related to paintings (for similar examples, see Rosenberg and Prat 1996 no. 338, Frankfurt; no. 321, London; see also the case of a drawing whose attribution has been challenged: no. R839 Washington). In these cases, the effect of the cut on interpretation is to create a hierarchy between the two sides of a sheet.

On the designation ‘recto-verso’

The aspiration towards ‘perfect visibility’ that strived to preserve the entirety of the support seems at odd with a ranking system based on the overall quality and material conditions of the work. The historicity of the criteria with which various professionals intervened in the material history of the sheets derives from the fact that interests and tastes changed over time (Guichard 2011). It so happens that, in the case of Watteau’s drawings, once these were taken out of the confines of the original album, the order of the loose sheets in a determinate sequence is lost and the two sides of loose sheets get ‘ranked’ more easily. With reference to the drawing by Watteau analysed above, a more definite provenance history detailing its ownership from the 18th century until the time when it was gifted to the National Gallery of Art in 1963 would allow a greater comprehension about the point in time when the recto-verso designation was determined, along with the pre-eminence of the side with the figure drawings.

At present, the drawing is known to have been in the collection of Charles Gasc, Paris, c. 1850; then with Richard S. Owen, Paris; until it was purchased by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, New York in 1937. Unfortunately, the moment at which the drawing was cut cannot be determined. Even in the absence of such information, material history can help to grasp the relationship between the treatment of drawings and the recto-verso designation. One of the most extreme alterations ever operated by Mariette, for instance, consisted in the splitting of a sheet in order to separate the front and reverse side and eventually juxtapose them (a technique which was adapted from his work with prints Smentek 2008, 47-53). Sale catalogues in the 18th century moreover were careful to describe double-sided drawings, wherever possible (on the language in 18th-century art writing, see Kobi 2017). Two sheets by Guido Reni, for instance, were described as landscapes in Mariette’s sale catalogue despite the fact that they had composition drawings on the reverse side:

Un beau paysage en travers, fait à la plume, et au verso se trouve le Couronnement de la Vierge, à la plume, et lavé. Un paysage en hauteur, dans lequel se voit saint Jérôme, et deux autres moyens paysages en travers, à la plume (Mariette catalogue, no. 642; Johnston 1969).

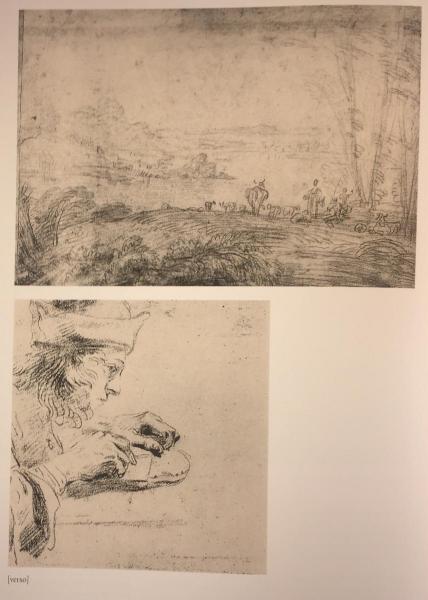

8 | Photo of a drawing of unknown location, from P. Rosenberg, L. Barthélemy-Labeeuw, Les dessins de la collection Mariette: école française, 2011.

While for 18th-century viewers both sides were worthy of equal attention, the practices of today’s museum have turned this description upside down: in actual fact, the Coronation of the Virgin is now designated as the recto of the sheet (National Galleries of Scotland, inv. no. D 702).

If compared with a drawing by Watteau which was described in the same catalogue, in a lot comprising “quatre études de paysages, des environs de Paris, à la sanguine”, it becomes clear that the criteria for the assessment of quality were still in the making [Fig. 8] (Mariette catalogue, lot. 1392).

The finished, sophisticated landscape on the side that was designated as the recto in the catalogue is typical of the artist’s free handling of red chalk that creates the receding planes in landscape pictures (see for comparison a drawing in New York, Rosenberg and Prat 1996 no. 18).

The sheet has been cut, in this case, along the margins of the landscape drawing, as the left part of the shoemaker’s body has been left out on the reverse side. The scholars who have compiled the catalogues raisonnés of both Watteau’s drawings and Mariette’s collection of French drawings have thus retained the original designation of the landscape as the recto, giving primacy to the degree of finish (Rosenberg Prat 1996, no. 224; Rosenberg and Barthélemy-Labeeuw 2011, no. F2967). Despite landscape’s lower status in comparison with figure studies, collectors seem to have appreciated Watteau’s accomplishment of a scene.

Thanks to the fact that Watteau systematically separated figure and landscape studies on different sides of the sheets, the historical and material study of his drawings allows us to appreciate the historicity of expertise and connoisseurship, all the while considering what we gain and what we lose in terms of meaning.

In this sense, some cuts have allowed connoisseurs and scholars to attribute more firmly certain sheets (see the case of Vasari’s Libro in Collobi Ragghianti 1974, 8), while others confirm the primacy of a more aesthetic taste for function and finish.

Conclusions

The history of the cut is therefore a history of conservation practices. Any alteration may be seen as the counterpart of the continued effort to preserve an object for posterity. In this sense, the study of cuts performed on drawings puts an emphasis on paper, drawing tools, and mounting – in short, on the technical history of drawing. Aided by the improvements in the quality of images and in technical diagnostics, recent art historical scholarship is turning attention to these material features as vital information for a deeper understanding of a work’s history (see for example the exhibition held at the Uffizi, Bacci et al. 1981; or for a more academic approach, Mussolin 2020). This means effectively entering an interdisciplinary sphere of study which brings together the various concerns of material conservation and the more theoretical interests of art history (see Rosand 2001).

Meanwhile, modern principles of conservation have radicalized Mariette’s approach to the restoration and display of drawings. By contemporary standards, conservators are very careful to maximize visibility of the marks on paper, including inscriptions and traces that have nothing to do with the original ‘drawing’, and to preserve the entirety of the paper support, for instance when they have to decide whether to separate a drawing from its original mount, if it could partially damage the original sheet (see James et al., 1997). It can even be argued that this principle lies at the heart of the modern discipline of conservation, as can be observed in Max Schweidler’s anecdote about the restorers who, in the 1930s, cut the margins of works on paper at the request of clients – something that he considered as absolutely incorrect (Schweidler 2006 [1938], 35).

In theory, we are therefore in the position to scrutinize drawings with unprecedented visual clarity, and yet, the study of drawing will always compel the viewer to face the material history that modify its very meaning, from the artist’s hands to the museum storage. Two types of ‘cut’ have been analysed here: the first kind allows collectors to juxtapose a drawing to another, even within the work itself, in order to supplement its comprehension, as in the case of Fra Bartolomeo’s landscape drawing; the second kind, conversely, reduces the possibility of reading the sheet in its entirety. For contemporary scholars and conservators, the first kind is considered as a peculiar form of ‘restoration’ (both in Collobi Ragghianti 1974 and in Smentek 2008), while the second has been condemned as an incorrect practice (Schweidler 2006 [1938]). This essay has argued that a diachronic material analysis of drawings can take into account both kinds of cut, from the moment when the draughtsman traced the first mark on the paper support, to the first alterations performed by the artist himself or by collectors at a later date. All traces of cuts found on drawings today require an interpretative posture that takes into account the complex history of the handling of drawing.

Bibliography

18th-century sources

- Jullienne, Figures

[Jean de Jullienne] Figures de différents caractères, de paysages, et d'études dessinées d'après nature par Antoine Watteau, Peintre du Roy en son Académie Royale de Peinture et Sculpture, gravées à l'eau forte par des plus habiles peintres et graveurs du temps, tirées des plus beaux cabinets de Paris, 2 vols., Paris, 1726-1728. - Lorangère catalogue

[E. F. Gersaint] Catalogue raisonné des diverses curiosités du cabinet de feu M. Quentin de Lorangère, composé de tableaux originaux des meilleurs maîtres de Flandres, d'une très nombreuse collection de desseins & d'estampes de toutes les écoles…, Paris, 1744. - Mariette catalogue

[F. Basan] Catalogue raisonné des différents objets de curiosités dans les sciences et arts qui composaient le cabinet de feu M. Mariette, Paris, 1775. - Mariette, Abecedario

[Ph. de Chennevières and A. de Montaiglon] Abecedario de P. J. Mariette : et autres notes inédites de cet amateur sur les arts et les artistes, 6 vols., Paris, 1853-1862.

References

- Bacci et al. 1981

Bacci et al., a cura di, Restauro e conservazione delle opere d'arte su carta: catalogo della mostra a cura del Laboratorio di Restauro del Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Firenze, 1981. - Bailey 1999-2000

C. Bailey, Toute seule elle peut remplir et satisfaire l'imagination. The Early Appreciation and Marketing of Watteau's Drawings..., exh. cat. Watteau and his world, A. Wintermute ed., New York, Ottawa, 1999-2000, 68-92. - Bjurström 2001

P. Bjurström, Crozat, Mariette, Tessin et le ‘Libro de’ disegni’ de Vasari, “Mélanges en hommage à Pierre Rosenberg”, Anna Cavina and Jean-Pierre Cuzin eds., Paris, 2001, 87-96. - Bleichmar 2012

D. Bleichmar, Learning to Look: Visual Expertise across Art and Science in Eighteenth-Century France, “Eighteenth-Century Studies”, 46/1 (2012), 85-111. - Caliandro 1999

S. Caliandro, Le Libro de’ disegni de Giorgio Vasari: un métatexte visuel, Limoges, 1999. - Chapman and Faietti 2010

H. Chapman and M. Faietti, exh. cat., Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings, London, 2010. - Collobi Ragghianti 1974

L. Collobi Ragghianti, Il Libro de’ disegni del Vasari, Firenze, 1974. - Dacier and Vauflart 1921-1929

E. Dacier, A. Vauflart, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIIIe siècle, 4 vols. Paris, 1921-1929. - Degenhart and Schmitt 1968

A. Degenhart, B. Schmitt, Corpus der italienischen Zeichnungen, 1300-1450, Teil I, Süd und Mittelitalien, 4 vols., Berlin 1968. - Eidelberg 1967

M. Eidelberg, Watteau's use of landscape drawings, “Master Drawings” 5/2 (1967), pp.173-182, and pp. 227-231. - Fischer 1989

C. Fischer, Fra Bartolommeo's landscape drawings, “Mitteilungen Des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz” 33 (2/3), pp. 301-342. - Forlani Tempesti 2012

A. Forlani Tempesti, Giorgio Vasari e il libro dei disegni: museo cartaceo o galleria portatile, in Giorgio Vasari e la nascita del museo, ed. Maia Wellington Gahtan, Firenze, 2012, 35-49. - Griener 2010

P. Griener, La République de l'œil: L'expérience de l'art au siècle des Lumières, Paris, 2010. - Guichard 2011

C. Guichard, Les Formes de l’expertise artistique en Europe, “Revue de Synthèse”, 2011-1, 1-13. - James et al., 1997

C. James et al. eds., Old master prints and drawings: a guide to preservation and conservation, trans. Marjorie B. Cohn, Amsterdam, 1997. - Johnston 1969

C. Johnston, Reni landscape drawings in Mariette’s collection, “The Burlington Magazine” 795 (1969), pp. 377-380. - Karet 1998

E. Karet, Stefano Da Verona, Felice Feliciano and the first renaissance collection of drawings, “Arte Lombarda” 124 (3), 1998, 31-51. - Karet 2003

E. Karet, The drawings of Stefano da Verona and his circle and the origins of collecting in Italy: a catalogue raisonné, Philadelphia, 2003. - Kobi 2017

V. Kobi, Dans l'œil du connaisseur: Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774) et la construction des savoirs en histoire de l'art, Rennes, 2017. - Kurz 1937-1938

O. Kurz, Giorgio Vasari's Libro de' Disegni, “Old Master Drawings” 45 (1937), 1-3; 47 (1938), 32-44. - Lajer-Burcharth 2015

E. Lajer-Burcharth, Drawing time, “October” 151 (2015), 3-42. - Lajer-Burcharth and Rudy 2017

E. Lajer-Burcharth and E. M. Rudy eds., Drawing: the invention of a modern medium, Cambridge MA, 2017. - Le Marois 1982

D. Le Marois, Les montages de dessins au XVIIIe siècle: l’exemple de Mariette, “Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français”, 1982, pp. 87-96. - Michel 2008

C. Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau», Genève, 2008. - Monbeig-Goguel 1987

C. Monbeig-Goguel, Le dessin encadré, “Revue de l’art” 76 (1987), 25-31. - Mussolin 2020

M. Mussolin, Palinsesti. Michelangelo e la carta, Milano, 2020. - Panofsky 1930

E. Panofsky, Das erste Blatt aus dem ‘Libro’ Giorgio Vasaris: eine Studie überdie Beurteilung der Gotik in der italienischen Renaissance; mit einem Exkursüber zwei Fassadenprojekte Domenico Beccafumis, “Städel-Jahrbuch” 6, 1930, 25-72. - Pomian 1990

K. Pomian, Collectors and curiosities. Paris and Venice 1500-1800, Cambridge, 1990. - Popham and Pouncey 1950

A.E. Popham and P. Pouncey, Italian drawings in the British Museum, the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, London, 1950. - Roland Michel 1984

M. Roland Michel, Watteau. Un artiste au XVIIIe siècle, Paris and London, 1984. - Rosand 2001

D. Rosand, Drawing acts: studies in graphic expression and representation, Cambridge, 2001. - Rosenberg and Prat 1996

P. Rosenberg and L.-A. Prat, Antoine Watteau (1684-1721): Catalogue raisonnée des dessins, 3 vols., Milano, 1996. - Rosenberg and Prat 2011

P. Rosenberg and L.-A. Prat, Watteau. The drawings, exhibition catalogue, London, 2011. - Rosenberg and Barthélemy-Labeeuw 2011

P. Rosenberg, L. Barthélemy-Labeeuw, Les dessins de la collection Mariette: école française, 2 vols., Milano 2011. - Rubin 1991

P. Rubin, Answering to names: the case of Raphael’s drawings, “Word&Image” 7 (1991), 33-48. - Schenck 2013

K. Schenck, et al. A Page from Giogio Vasari's Libro de' Disegni as Composite Object, “Facture” 1 (2013), 2-31. - Schweidler 2006 [1938]

M. Schweidler, The restoration of engravings, drawings, books, and other works on paper, Los Angeles, 2006 [1938], trans. Roy Perkinson. - Smentek 2008

K. Smentek, The collector's cut: why Pierre-Jean Mariette tore up his drawings and put them back together again, “Master Drawings”, 46 (2008), 36-60. - Smentek 2014

K. Smentek, Mariette and the science of the connoisseur in eighteenth-century Europe, Burlington VT, 2014. - Tillerot 2011

I. Tillerot, Engraving Watteau in the eighteenth century: order and display in the Recueil Jullienne, “Getty Research Journal”, 3 (2011), 33-52. - Tordella 2012

P. G. Tordella, Il disegno nell'Europa del Settecento. Regioni teoriche ragioni critiche, Firenze, 2012.

English abstract

Between the 16th and the 18th century, as the study of drawing emerged as a scientific procedure to write the history of European art, material cuts have transformed the way in which drawings were collected and studied. This essay examines various types of cuts, such as those operated on the drawings in the collections of Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) and Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774), and offers an explanation on how such treatment shaped the interpretation of scholars and connoisseurs through time. The case of the loose sheets by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) shows the impact of the cuts made since the 18th century on the study of an artist’s drawn oeuvre, and particularly on the ranking of pictorial genres. Landscape drawings are cut to favour figure studies on the opposite face of the sheet. Starting in the 19th century, the systematic introduction of the labels ‘recto’ and ‘verso’ in art historical literature and museum practices has resulted in the hierarchical arrangement of the two faces, according to the evolution of taste. The philological study of the loss caused by the cut, it is argued, may promote fruitful intersections between the history of drawings’ connoisseurship, collecting and restoration.

keywords | cuts; drawing theory; Watteau; Mariette; recto-verso; landscape drawing; collecting taste

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio.

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo/ To cite this article: Camilla Pietrabissa, Cutting down the interpretation of drawings. The case of Watteau, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 179, febbraio 2021, pp. 33-50. | PDF dell’articolo