At the border of artistic legitimation

Geography, practices and models of project spaces in Milan

Laura Forti, Francesca Leonardi

English abstract

Introduction. The art system

In Italy, in the last ten years, a multiplicity of project spaces has taken place especially in Milan, following the previous “generation” of independent venues which opened in the first decade of the 21st century (Sperandio 2010). Looking at this phenomenon, it must be acknowledged that the origin of independent exhibitions and spaces in the art field can be traced back to mid-19th century [1]. In 1884, for the first time, the word ‘independent’ was used by the Salon des Indépendants organized by the Society of Independent Artists. It was a very liberal society, that exhibited all the artists who wished to participate, with no selection or jury. In 1903, in Paris, the Salon d’Automne was set as an independent exhibition, alternative both to the official Salon and to the Salon des Indépendants, since it showed the works of young artists but at the same time it was chaired by a jury. This effort toward an artistic independence was part of a broader socio-cultural change that opposed the bourgeois values to the bohemian lifestyle, where the intellectual freedom of the artist contrasted with the commercial art produced for the bourgeois market. This contraposition was encountered not only in the artistic field but in every cultural production: for instance, as analyzed by Bourdieau (Bourdieau 1992), Flaubert and Baudelaire it played a major role in the conquest of autonomy of the literary field. Therefore, independence in the cultural field arose from the necessity of intellectual freedom of the artist, and this would have led to the formation of the artistic avant-gardes and to the formation, in the last decades of the 19th century, of the art market as we came to know it.

The gallery-based art system, indeed, was the result of this socio-cultural transformation: from the rigid academia-controlled art production to the bohemian artist supported by visionary gallerists who, together with collectors and critics, created the market for him. The art market, or better saying the art system, started to look as an ‘artworld’ with its own internal rules and paradoxes, as philosopher Arthur Danto defined it: “to see something as art requires something the eye cannot decry—an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld” (Danto 1964, 580). He thought that what distinguishes art from non-art is the ability of some people to understand and position the artwork into a theory of art. The philosopher George Dickie elaborated on this concept up to the formulation of the Institutional Theory of Art (Dickie 1974)—that is the theoretical framework in which this article is also grounded. Dickie stressed the institutional aspect of the art system, meaning the network of relations which constitutes it: “by institutional approach I mean the idea that works of art are art as the result of the position or place they occupy within an established practice, namely the artworld” (Dickie 1983, 47). What Dickie addressed with institutional theory is the complexity of relations which defines and structures the art system [2]. The artworld (or framework) is composed of different actors, which both Dickie and the sociologist Howard Becker described (Becker 1982): both of them stressed the multidimensionality of the artistic production, meaning that an artwork includes the collaborative work of many professionals with different competences and the adoption of a set of conventions [3]. It emerged that even if rules may not be explicit, the structure and functioning of the contemporary art system is highly regulated; indeed, Becker used the word “cooperation” to describe how the artworld works [4].

This pattern of collective activity can be visualized from the perspective of the career of the artist: on one side there is the multitude of artists who have graduated from art schools and have a little production of artworks. On the other artists, generally after studying, participate in art residencies in order to develop their artistic research and produce some artworks (usually residencies have a production budget). Then, the artist somehow manages to get represented by a small gallery which puts him on the market. Critics start writing about him and curators invite him to show in their exhibition space and later in biennials. The fame and appreciation for the artist should grow sustainably for the rest of his career: he should exhibit in more and more important museums, passing from a smaller to a bigger gallery getting access to global fairs, and his prices should steadily grow. Of course, this status creation process takes place neither at the same speed nor in a linear way for all the artists. As a matter of fact, very few of them manage to become ‘stars’ of the sort that are included in the collections of the most important museums and achieve record prices on the market.

Project spaces at the border of artistic legitimation

The position of independent spaces (or project spaces) in the art system is between academia and the first gallery experiences. They embody a very important phase in the career of the artist indeed: when he/she for the first time exhibits his/her work to a public and starts confronting the art system. Small galleries usually pick up emerging artists from project spaces, which are often the first showcase opportunity for them. Whereas in other countries the final year exhibition of art students is a very crowded event, attended by gallerists and museum curators, in Italy few significant exhibition opportunities are provided by schools, and they are generally considered not attractive. The lack of official endorsement from academia and the general scarcity of public grants for artists make project spaces a vital and fundamental resource of the system. In this sense, project spaces are the first gatekeepers of the art system and sit at the border of artistic legitimation.

Focusing on the independent scene in Milan through qualitative interviews to curators and founders of art spaces, this research studies the challenges and characteristics of project spaces by addressing their organization, identity and relations with other actors of the system. The notions of independence and interdependence are here investigated in relation to the spaces’ identity and activity: how do they balance intellectual and financial autonomy? How can they avoid the risk of isolation? Can common rules or organizational models be identified? Finally, which are the most relevant objectives of these spaces: visibility, legitimation, research or innovation?

It is important to address a terminology issue: the authors prefer to use the term “project space” instead of “independent space” because the majority of the curators interviewed recognized it as more appropriate and in line with their ideas and purposes. Apart from terminology, the instances brought up in the past by independent spaces and their relationship with the art system are very similar to the project spaces’ ones. In the first part, the article focuses on the concept and organization of the spaces, addressing issues of identity, curatorial choices and budget; in the second part it visualizes the formal and informal relationships between spaces, artists and founders through a network analysis; in the conclusion, a morphology of project spaces is outlined, identifying three main models: the research space, the hybrid space and the proto-gallery.

Literature review

Even if, internationally, studying and mapping project spaces and creating archives is a relatively common practice (Young 2016 on Halifax; Tavano Blessi, Sacco and Pilati 2011 on Montreal; Picard 2009 on Chicago; Miles 2005 on Melbourne; Wilczek 2010 on UK), apparently there is not much specific literature about contemporary project spaces in Milan or in Italy. Among international publications, Murphy and Cullen (2016) is maybe the most similar research to this one: it looks at the conditions, organizational models and role of spaces in Europe within contemporary art and society, even if it does not include network analysis in its methodology. Mapping seems to be the most common strategy in order to fight the temporariness and sometimes evanescence of project spaces; the online platform artist-runspace.org is a global database, but very few Italian spaces are detected and put on the map (11 project spaces in Italy and only one in Milan).

The main reference in the Italian field is “Italian Cluster”, an independent research by Giulia Floris and Giulia Ratti published in 2019. It is a collection of 13 in-depth interviews with various professionals who manage, participate, observe, finance and inspire project spaces in Italy, with infographics and data. The publication does not aim to be an exhaustive research nor an updated map of Italian project spaces, since their speed of opening and closing is almost uncatchable: the major point of their study is to shed light on the independent dimension, in order to initiate a discussion on its challenges and issues. Even if it is not a scientific nor systematic one (interviews do not follow a geographical criteria of selection), the study has the merit of gathering primary information on spaces and collecting testimonies in different geographical areas of Italy.

On the use of network analysis in the cultural field, and more specifically in the contemporary art system, literature is richer. The major reference is the work of the Observatory on Contemporary Art of ASK Research Center (Università Bocconi), where the authors of the article also worked. The exploration of the Observatory was carried out on the visibility, the recognition and the processes of verification of contemporary art production between 2005 and 2013. In particular, Baia Curioni and Rizzi (2016) uses network analysis to understand the convergence between the market-oriented actions of commercial art galleries at the Art Basel fair and the exhibiting choices in the museum environment. Another important reference is the work of Mitali and Ingram (2018) which uses network analysis applied to abstract artists of the early 20th century. The research finds out that an artist in a brokerage, rather than a closure position, is likely to become more famous; that rather than creatitivity, brokerage networks associated with cosmopolitan identities are perhaps the key social-structural drivers of artists’ fame.

Within organizational studies, Di Maggio (1982) analyses Boston’s cultural entrepreneurship scene in the 19th century and the creation of an organizational base for high culture. He addresses the context of cultural capitalism by focusing on the Museum of Fine Arts and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, concluding that the alliance between class and culture is defined by its organizational mediation.

On the notion of entrepreneurship, Klamer (Klamer 2011) studies the figure of the cultural entrepreneur, who shows similarities with artists or curators running project spaces, and questions his/her peculiarities and role in the economic system. Gehman and Soublière (Gehman and Soublière 2007) analyze three perspectives on cultural entrepreneurship: making culture, meaning the processes by which high culture organizations and popular culture products are created; deploying culture, or the processes by which culture constitutes a toolkit for legitimating new ventures; and cultural making, meaning the distributed and intertemporal processes whereby value is created across multiple and fluid repertoires and registers of meaning.

Lastly, on the notion of independence in the cultural and artistic field the literature is extremely rich, to cite just a few: Bourdieu (1992) on the conquest of autonomy in the literary field, Bennett and Strange (2015) on the independence in the music and media sector. However important, these last publications are not the primary references in terms of methodology and discipline for this article, so the authors limit themselves to just acknowledge them.

Methodology and sample

In the initial phase of the research, the authors have collected different lists of project spaces in Milan from some cultural aggregators’ databases, such as “Zero”, “That’s contemporary”, “Untitled” [5] and “Italian Cluster”. A comprehensive list of independent spaces in Milan was finally created. On a total of 69 independent or cultural spaces detected in Milan, a selection of 39 spaces has been found based on the following criteria:

– the project space needs to have a physical location (no online projects);

– it must be located in Milan;

– it has agreed on answering to our questions;

– even though we did not discriminate between private and public spaces, for the purpose of this article and for reasons of comparability, no public institutions have been taken into consideration.

The sample includes the following project spaces: /77, Armada, Assab One, Brown Project, Casacicca, Circoloquadro Arte Contemporanea, Converso, Current, Dimora Artica, Edicola Radetzky, Erratum, Espinasse 31, Fantaspazio, FuturDome, Galleria Inconsueta, Il Colorificio, La Casa di O, Le Dictateur, Lucie Fontaine, MARS, Marsélleria, Mega, On Off, Pelagica, Sblu Spazio al Bello, Spazio Cabinet, Spazio Gamma, Spazio Nour, Spazio O’, Spazio Serra, SpazioFico, Standards, Studiolo, T-space, The Open Box, The Workbench, Uno a uno, Vegapunk, Xcontemporary.

Given the peculiar nature of these realities, qualitative data have been gathered through structured interviews to their founders [6]; while quantitative research has been carried out on the list of artists who have exhibited in these spaces in 2018 and 2019. The period of analysis of the article, which coincides with the period of data collection, are the years 2017, 2018 and 2019. The structured interviews are divided in three major paragraphs: Identity, Organization and Relations. The first part focuses on the concept of the space and on the idea of independence; the second part investigates the organizational structure and the financial aspect of it; the last part collects the relationships between the space and the actors of the art system, in order to create the network analysis. Interviewed spaces gave multiple answers to some questions (e.g. multiple criteria, definitions, activities, ect.), that is why some results may exceed the total number of spaces. Interviews and additional desk research allowed to build a dataset of 840 artists and more than 1,000 art events held in the selected 39 Milanese project spaces from 2017 to 2019. The network analysis has been carried out with UciNet (Borgatti et al. 2002).

1. Identity of project spaces

Considering the overall sample, a growing trend of new project spaces can be seen between 2015 and 2017, during which 18 new spaces have opened. From 2001 to 2018, only five spaces have closed due to different reasons: some of them just reached their purpose, respecting their nature of project with a beginning and an end (Brown Project, /77, Marsélleria); others changed completely their identity from project space to a co-working (Lucie Fontaine) or a publishing company (Le Dictateur). They are small spaces, usually both in terms of square meters and in terms of public: on average they attract 150 persons per exhibition and each exhibition lasts approximately two months. Generally, the public is composed of professionals and students from the art world (25 project spaces) and less frequently by generic people or neighbors (14). Legally speaking, project spaces generally assume the juridical form of non-profit cultural associations (24), some of them are private property spaces (8) open to the public, few of them (4) are supported by a company or have an additional for-profit activity supporting them and others (4) have different informal settings: some begin as a squat activity in an occupied place (Galleria Inconsueta), others are nomadic not structured curatorial activities (/77, Uno a uno) or informal organisations in temporary rented places (Lucie Fontaine). Notwithstanding their different legal form, the prevalent activity of those spaces can be identified with organising exhibitions and being a space for experimentation and research in the artistic field.

When asked if they find themselves in the term ‘independent space’ a rich discussion followed over the meaning of independence. Those who recognised themselves in that terminology (64%), defined independence in a twofold way: economic independence and curatorial independence. The first means not only that they provide for their own financial support, but also that they feel out of the art market logics and dynamics in managing the space. In this sense, independence is strictly related also to curatorial choices. This translates in the freedom of working with artists in a non-continuative way (as galleries usually do), in the possibility to focus on the creativity of the artist and not on the selling of his/her works and in being autonomous in every stage of the project. Curatorial independence also was linked to improvisation, openness, fluidity, freedom of expression, freedom of choosing artists independently from market trends. So ‘independent space’ signifies curatorial freedom, managerial autonomy and experimentation—which undoubtedly are the positive aspects of every project space. However, those who refused or partially agreed to be associated with that term (35,8%) interpreted the meaning of independence as being ‘isolated’ from the system or as an outdated adjective signifying ‘alternative’ to the mainstream. Their point is that it is impossible to be independent from the art system, in fact, in order to have a voice, the space needs to be in relation and in connection with it.

Interdependence with the art system and the importance of creating a network of relationships have been highlighted by several spaces as a fundamental element. The discussion helped in de-structuring the meaning of independence and highlighting its paradoxes: spaces need to be independent from the logic of the market and need to embody their curatorial freedom in offering a place open to research and experimentation; at the same time, they need to financially survive and being taken into consideration by the system. The discussion also provided a new vocabulary: in general, ‘project space’ seems to be the most appropriate term to use because it includes a temporary attitude and openness to different formats and objectives. Other terms which have come out in addition to project space and independent space, are: artist-run-space, curatorial reality, private kunsthalle, platform, artist residence. Some of these terms highlight specificities of single spaces which are run by artists or perform a specific activity (artist’s residence), whereas the others emphasize its curation and exhibition. Even if some of these terms refer to realities well-studied by art history, they cannot be fully considered synonyms of ‘project space’ because they are too specific and unable to include the complex diversity that the term implies.

Looking at their operational behaviour, obviously the main selection criteria curators or artists follow is their personal curatorial taste – which is coherent with the curatorial independence mentioned earlier. Most of the founders are emergent curators or artists, so it is easy for them to know other emerging artists and support each other. Some of them admit that they choose artists amid their personal network or coming from a specific university (usually Accademia di Brera). Some project spaces focus on emerging artists (6), whereas others (3) prefer to exhibit established artists. Both of these are legitimation strategies: the first one aims to legitimize the space as cutting-edge for emerging talents, the second uses the prestige of established artists in order to legitimize the space. Other spaces (4) select artists that work with a specific technique (e.g. painting, sculpture, etc.) because of a curatorial statement or peculiarities of the space.

An important observation comes from the criteria which projects spaces use in evaluating their activity.

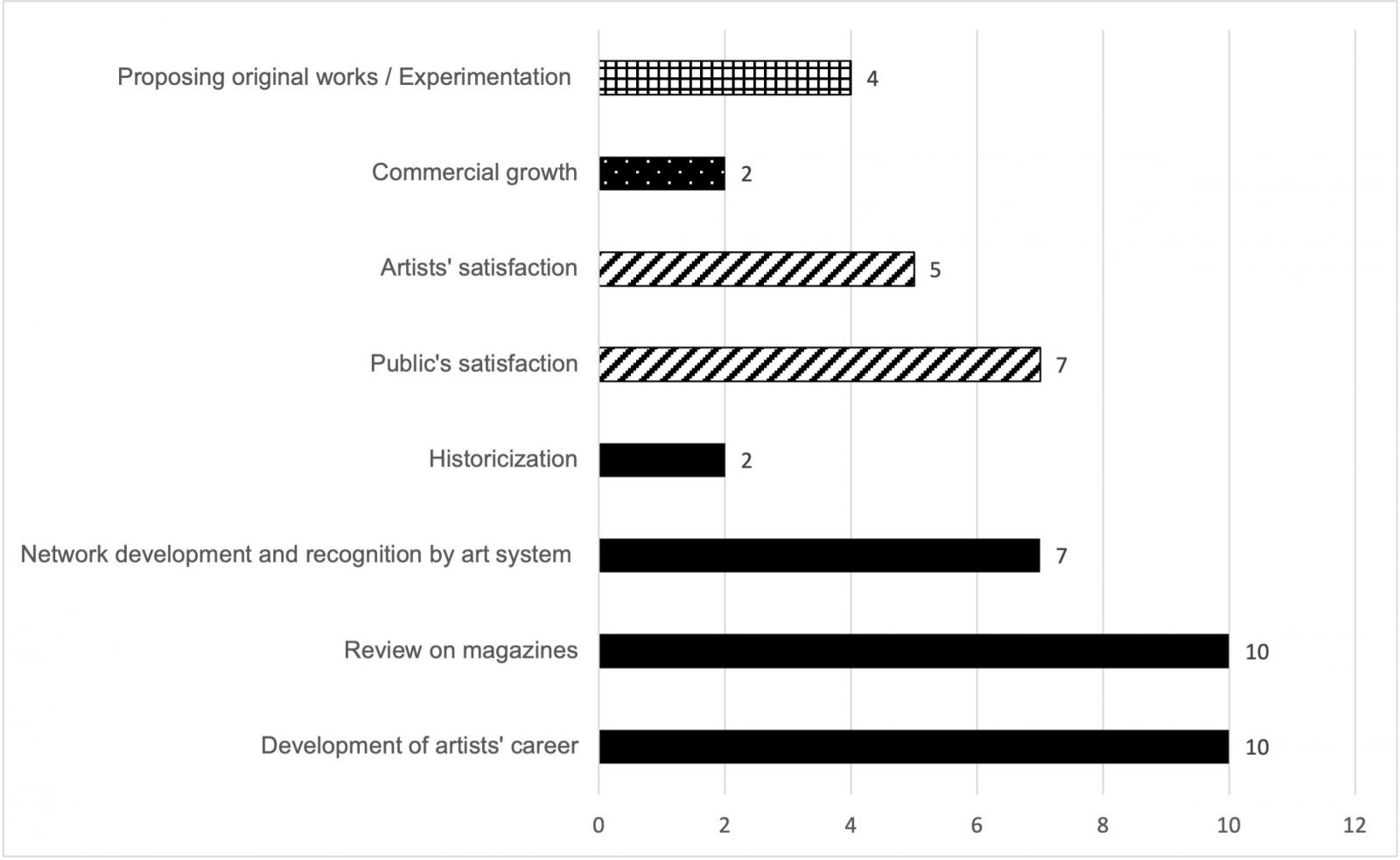

1 | Criteria of success, Key: black= legitimation by the system; stripes=social appreciation; dots=commercial; squared= research. Note: total may vary because of multiple answers. (Source: Interviews)

If most of them have stressed the importance of curatorial independence and freedom of their practice, however, when it comes to evaluate the success of their program, the vast majority of them use criteria tied to legitimation by the system [Fig. 1]. Legitimation (black in the graphic) comes mainly from the development of artists’ career after they exhibited in the space and by the reviews on art magazines. Particularly important is enlarging the network, meaning obtaining collaborations with important institutions and galleries, which gives legitimacy and importance to the project space. This demonstrates that even if spaces want to act or to be perceived as neither dependent on the market nor on power dynamics, this is not truly possible since they rely on their judgement and approval. Furthermore, two spaces – which are now closed – mentioned as their success criteria the fact that they have been historicized: again, it is the recognition and legitimation over time by the system that decrees the relevance of a project. Appreciation by the public and by artists are also relevant indicators: it signifies that the impact of these places is evaluated also on a social level (stripes in the graphic). The increase of visitors’ number and the increase in artists’ proposals is taken as an indicator of success and appreciation. Counterintuitively, the merit of exhibiting for the first time artists and brand new works is valued only by few spaces as a criteria of success (squared in the graphic). Finally, two spaces indicate the commercial growth as their criteria of evaluation (dots in the graphic) – which suggests that legitimation may not be sufficient for the sustainability of the space.

The specificity of the place of a project space is either particularly poignant or completely irrelevant in relation to the exhibition program. For some spaces the curatorial project is consequential to the place in which it is set. For instance, Casacicca is a private house where artists live for a period and leave their work there as a gift. The Open Box derives its name from the fact that it is a car box turned into a project space. Edicola Radetzky is a dismissed news stand which now hosts installations and sculptures: the fact that it has windows all around convinced the curators to choose only sculptures to be displayed there because they can be appreciated from all the perspectives by passengers. Converso has as its main objective to open spaces closed to the public and to exhibit artworks which confront the place. For other project spaces the choice of the place has been more random and defined more by the real estate market than by curatorial taste.

2. Organisation of project spaces

Concerning funding, the major source of revenues for 74% (29 out of 39) of project spaces is self-funding. Of these, 13 are the spaces whose only supporting means is self-funding, whereas the rest have mixed funding. Only 26% of project spaces are able to get external funding (sponsors) or public grants to cover the costs. External or collateral sources of revenues other than public grants are: sponsorships, offering the space to rent for workshops or courses and creating a membership or subscription card. This last option is also used to create a community of supporters and to engage the public with the space. Starting a business collateral to the exhibition space (e.g. Spazio Gamma with the library) is a good way to partly cover costs, even though it drains energy and funding itself. In this way project spaces become hybrid spaces with different and synergic souls. Since there is such great diversity between funding, the annual budget greatly varies too: it goes from a minimum of 3.000€ (basically covering the bills) up to 120.000€ (when supported by a company).

It is necessary to note that usually curators and founders who work in these spaces (when they are not funded by commercial companies) do not get a salary. Indeed, generally founders of project space have another job which provides them their main salary. Moreover, all of them work in the cultural sector and the vast majority of them in the art field. For this reason, their contribution to the project space is residual and highly influenced by their primary job, also in terms of relationships within the system.

One of the most sensitive issues with which project spaces have to deal with is selling artworks, since according to Italian legislation they generally could not (or, rather, it depends on the juridical form of the organization). For this reason, the majority of spaces do not sell artworks, they limit their intervention to put the collector in contact with the artist. Those who sell artworks, they either legitimately can because of statutory declarations, or they do it through donations. This is a consequence of a lack of bureaucratical flexibility to address specific issues in informal associations.

Finally, in an art world in which rules are not written but widely shared, it came with little surprise the acknowledgement of a lack of explicit ethical rules in the management of the space. In fact, when asked if curators perceive a conflict of interest in working in more than one space, the majority has answered that they see no conflict whereas only four spaces said that they would avoid doing so. Working in galleries or cultural institutions and curating their own project space is not perceived as incompatible, whereas the same operation in another sector would probably be. Indeed, curators admit that they can run the space thanks to their primary occupation, not only in terms of funding but mainly in terms of connections with artists and other actors of the system. Moreover, when asked if the founders-artists use the project space to exhibit their work, 15 spaces answered that they do, while only 7 say they do not. This is an explicit self-legitimation practice in which emergent artists who are not represented by galleries rent a space in order to be noted by the system. Usually operations like this, whose aim is entering the system and the market for the first time, are done by independent curators who select the most interesting artists and organize a show (e.g. talent scouting). That is why many project spaces are run by emergent artists or emergent curators: it is a collaborative way to autonomously get visibility in the system in their very initial career. On the other hand, artist-run-spaces have a long tradition: usually they start in the studio of an artist who invites other artists to show their work. This practice is generally detached from commercial implications and it is aimed at creating a community of artists who sustain each other’s research in a fruitful way. This is the case of MARS (Milan Artist Run Space), a decennial project born in an artist’s studio whose initial objective was to create a space for discussion and experimentation between artists. However, nowadays not all the spaces who define themselves as ‘artist-run-space’ share the same intentions: some resemble a window-shop for the art market, which closes once the gallery picks up the artist.

So, the initial phase of the legitimation of the artist is a very interesting and complex experience: it spans from confrontation and research with other artists to get visibility on the market. Self-legitimation strategies are very diffused in the art system and they are quite coherent with the temporary attitude of project spaces: these are platforms of experimentation and visibility, which close once their purpose terminates.

3. Relations and Network analysis

It is interesting to analyse the attitude to conduct autonomous artistic research and the notion of independence in a network perspective, as discussed in the interviews. Considering all the events and projects organized in the 2017-2019 timespan, we can check which artists are shared by more than one project space in Milan, and which are exclusively shown by a specific one.

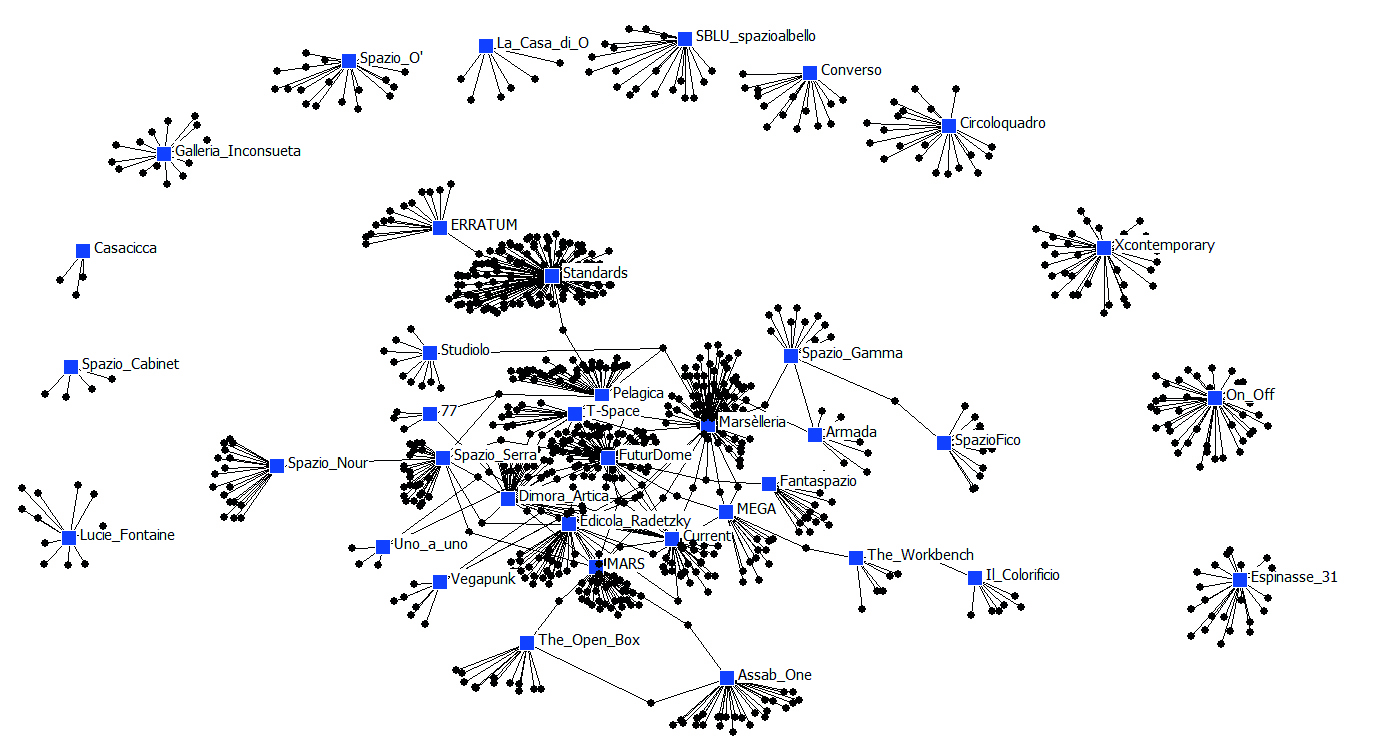

The resulting network ([Fig. 2] where blue squares represent the art spaces, and the black dots represent the artists) clearly suggests the presence of ‘islands’. On 37 project spaces (Brown Project and Le Dictateur, included in our sample, were not active anymore from 2017 to 2019), nearly one third (12) do not have any artists in common with the other independent spaces working in the city, and other 8 spaces have a weak connection through just one artist. We can assume that these realities program their activities with a marked independence and select their artists without an exhibition history within the local independent scene. Besides, only the 6% of the artists in our dataset (48 out of 834) is shown by more than one project space. These artists are young (half of them is under 35 years, 3 out of 4 are under 40 years) and nearly all Italian-born (the 92%), with some experience abroad; the 70% is male, thus suggesting a significant unbalance in the promotion of emergent artists. Around them, we can see a nucleus of 17 spaces that have links with more than one space. This can be interpreted in different ways: it could be the result of an explicit collaboration, a sign of the capability to influence other spaces’ choices, or just a consonance of artistic taste; the presence of the same founder or curator is not so relevant, occurring in just two cases. At the very centre of the network we find spaces that share more than 10 artists: Dimora Artica (14 artists), Current (13), Marsèlleria (12), FuturDome (11) and Edicola Radetzky (10), immediately followed by MARS (9).

2 | Network of project spaces and artists exhibited, 2017-2019.

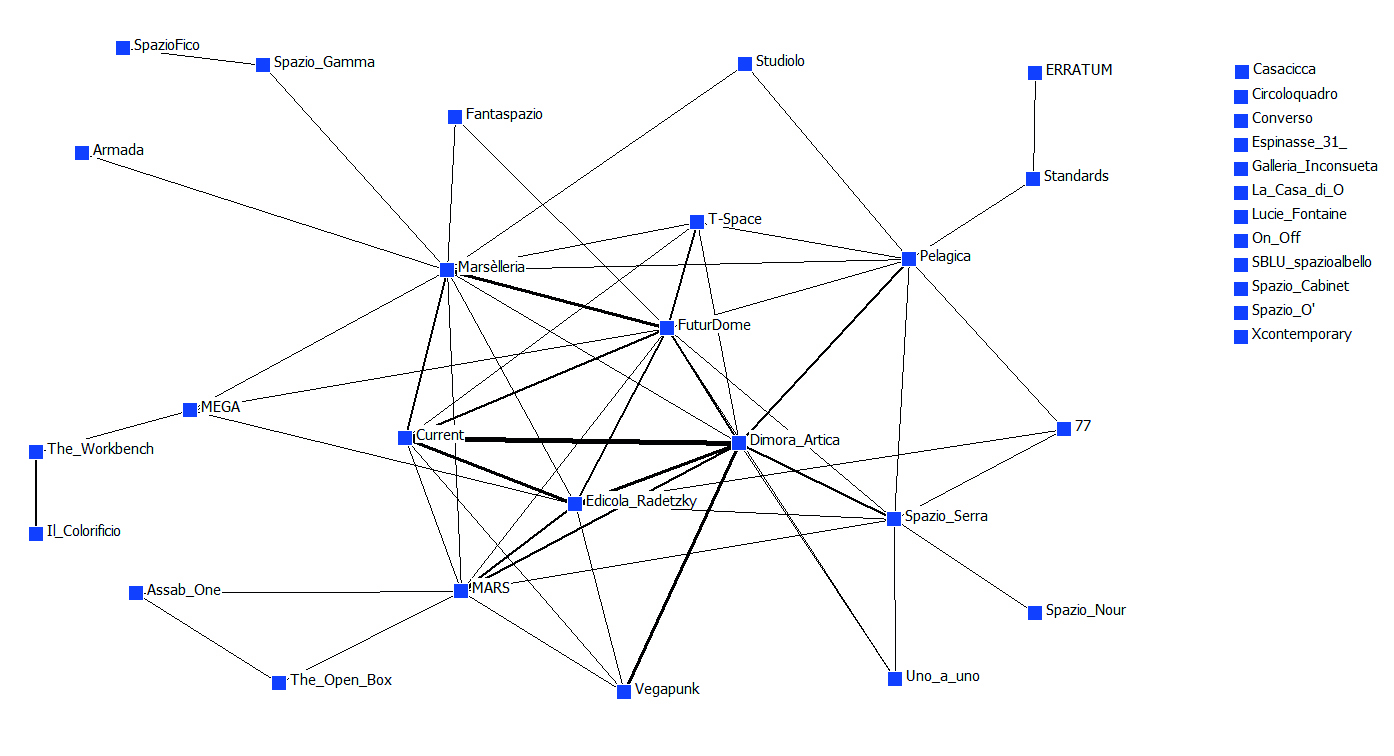

We also represented the implicit relationship among spaces [Fig. 3], connecting them if they have artists in common (the thicker the line, the more the artists they share). We can recognise stronger links between some of them: for instance, Dimora Artica and Current, Dimora Artica and Futurdome, Dimora Artica and Vegapunk, FuturDome and Marsèlleria.

3 | Network of Connections among project spaces with one or more artists in common, 2017-2019.

The nature of these links, more or less intentional, can be developed through initiatives that incentive partnerships and collaborative projects, events and platforms helping these kind of spaces to know each other and make their programs more visible. Many of them (10) take part in Fuori MiArt, a dedicated section of the contemporary art fair of Milan, while others participate in diffused events opening artists’ studios and spaces (Spazi Aperti, Studi Festival). Moreover, some spaces actively organise specific initiatives to create connections, and this is particularly interesting in a context in which, as represented in the previous figure, ‘off’ projects tend to develop isolated curatorial choices. With Outer Space in 2017, FuturDome invited ten independent spaces to exhibit, showing the overall art system their great potential. In the same year, Rose Bouquet, a two day-long workshop at Marsèlleria, was intended as a collective portrait of different artistic contexts sharing intentions, struggles and an aptitude to rethink organizational structures.

Conclusions. A morphology of project spaces

Even if the project spaces analysed in this article widely differ between one another, three major typologies can be found: the research space, the hybrid space and the proto-gallery.

The research space is a place dedicated to experimentation and artistic research and it is detached from commercial constraints. For this reason, it is often managed by artists, possibly in their studio, or by emerging curators who want to realize a creative curatorial idea. It is a space for training and development for young artists who just graduated from art schools. It can be indirectly managed or influenced by professors acting as mentors, as in the case of Armada where the artist-professor gave the space to his students and the place is currently used by students of Accademia di Brera. It is self-financed and this is why it can be short-lived: either new generations of artists take care of the space or it closes following its founders’ careers. This is particularly true for spaces intended as ‘curatorial projects’ which generally close in a few years, after having attracted enough visibility from the system.

The hybrid space is a more complex organisation in which the exhibition program is sustained by a commercial activity usually carried out in the same space. These are not the spaces of commercial companies who use them as a pop-up shop, on the contrary here there is an entrepreneurial business beside the exhibition activity. Some of these activities may be in relation to the exhibition program, as in the case of Spazio Gamma which has a library and invites artists working with graphic design and editorial products. In this instance the activities are synergic and enable the space to get specialized in a niche sector. Another good example are spaces which organise artists’ residencies and then exhibit their work in the space. However, hybridity does not just mean a simultaneous presence of more than one activity, but also a path of hybridization: a space can start as an exhibition space and then it can become something different following founders’ specializations. For instance, T-space was born as a project space dedicated to contemporary photography and lately has become a photographic studio offering photographic services. Another example is Le Dictateur whose identity has always been on the threshold of an exhibition space and an editorial project: once the space closed, it continued as an editorial company collaborating with artists.

The proto-gallery model represents all those project spaces seeking to become a gallery. Frequently curators (who later become gallerists) open project spaces as cultural non-profit associations to try to navigate the art system without competing directly with galleries. Later, once they have strengthened their relationships with artists and collectors, they complete their transition into a commercial gallery. During this phase, they do occasional sales and try to create contacts with collectors. In this case, the project space serves as a moment of learning and observation of the dynamics of the art system.

Project spaces have some internal challenges in common, such as the gentrification effect, which almost directly follows the opening of artistic spaces in a specific city area, or limited access to funds, which is directly related to their informal or little structured organization. If the ‘independence’ claimed for their cultural activity risks to become a fragile isolation (both in terms of visibility and sustainability overtime), the participation to debates, exchanges, dedicated events can make spaces more aware of the central role they play in the art system: they are the first gatekeepers and the first opportunity for emerging artists who can be noticed and later picked up by galleries. Moreover, as some interviewed curators have said, there is a big representation gap of emergent artists in Italy: in opposition to what happens abroad, generally galleries in Italy tend to show international emergent artists rather than Italian ones because of a supposed matter of prestige. Project spaces cover that gap by exhibiting young Italian artists who otherwise have no chance to enter into the artistic scene. In conclusion, project spaces meet structural needs of the contemporary art field, especially in Italy.

Further research, given the peculiarities of this period, should analyse Covid-19 effect on the art system, especially if and in which measure the online channel has created a disintermediation of traditional structures in the system.

Notes

[1] The first independent spaces can be identified with 1855 Courbet’s Pavillon du Réalisme in Paris, which was organised next to the Exposition Universelle. Later in 1863, Napoleon III organised the Salon des Réfusés in Paris in order to show the paintings not selected by the official Salon. All these events showed a clear opposition to the official evaluation criteria of the Salon and the rigid cultural discourse of academia, up to the point that this necessity to self-identify as an independent and not institutional movement was pursued in 1874 with the first exhibition of Impressionists in Nadar’s studio in Boulevard des Capucines.

[2] “The institutional theory attempts to place the work of art within a multi-placed network of greater complexity than anything envisaged by the various traditional theories. The networks or contexts of the traditional theories are too thin to be sufficient. The institutional theory attempts to provide a context which is ‘thick’ enough to do the job”, Dickie 1983, 47.

[3] “What is primary is the understanding shared by all involved that they are engaged in an established activity or practice within which there is a variety of roles (...) Our artworld consists of the totality of such roles with the role of the artist and the public at its core”, Dickie 1983, 52.

[4] “The forms of cooperation may be ephemeral, but often become more or less routine, producing patterns of collective activity we can call an art world”, Becker 1984,1.

[5] “Zero”, “That’s contemporary” and “Untitled” are online magazines and blogs dedicated to the artistic scene of Milan. They agreed on collaborating with the authors and sharing their databases.

[6] Interviews have been done with the collaboration of Accademia di Brera’s students, who attended the course “Economia e mercato dell’arte” in 2018 and 2019.

Appendix: structured interview

BASIC INFORMATION

Address

Legal form

Number of projects per year and how to access

Description of the last projects

IDENTITY

Aims of the project space

Self-definition (independent space, project space, artist-run space…)

Meaning of the notion of “independence”

Other spaces considered as a reference

How artists and projects are selected

Choice and relation with the physical space

Self-assessment criteria

RELATIONS

Description and dimension of the audience

Map of relations with other private and public institutions in Milan

Relations within the neighbourhood

Participation to organized events for project spaces

Eventual collaborations / partnerships

ORGANISATION

Funding sources

Eventual rules / code of ethics

Communication of activities, relationship with reviews

Names and biographies of founders and curators

Relationship with other professional activities (founders and curators)

Projects and vision for the next 5 years

Bibliography

- Baia Curioni, Rizzi 2016

S. Baia Curioni & E. M. R. Rizzi, Two realms in confrontation: consensus or discontinuity? An exploratory study on the convergence of critical assessment and market evaluation in the contemporary art system, “Museum Management and Curatorship”, 31/5 (2016), 440-445. - Becker 1982

H. S. Becker, Art Worlds, Berkeley 1982. - Bennett, Strange 2015

J. Bennett and N. Strange, Media Independence. Working with freedom or working for free?, London and New York 2015. - Borgatti, Everett, Freeman 2002

S.P. Borgatti, M.G. Everett and L.C. Freeman, Ucinet 6 for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis, Harvard 2002. - Bourdieu [1992] 1996

P. Bourdieu, The rules of art. Genesis and structure of the Literary Field [Les Règles de I’art, Paris, 1992], translation by S. Emanuel, Stanford, 1996. - Danto 1964

A. Danto, The Artworld, “The Journal of Philosophy”, 61/19, American Philosophical Association Eastern Division Sixty-First Annual Meeting, (1964), 571-584. - Da Pieve 2018

D. Da Pieve, Indipendenti?, “Forme Uniche”, 17 May 2018, accessed 20 February 2021. - Dickie 1983

G. Dickie, The New Institutional Theory of Art, “Proceedings of the 8th Wittgenstein Symposium”, 10 (1983), 57-64. - Dickie 1974

G. Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic, Ithaca/London, 1974. - Di Maggio 1982

P. Di Maggio, Cultural Entrepreneurship in Boston, “Media, Culture and Society”, 4/1 (1982): 33-50. - Floris, Ratti 2019

G. Floris and G. Ratti, Italian Cluster, Self-published project, 2019. - Gehmann, Soublière 2017

J. Gehmann and J. Soublière (2017), Cultural Entrepreneurship: from making culture to cultural making, “Innovation”, 19/1, 61-73. - Klamer 2011

A. Klamer, Cultural entrepreneurship, “The Review of Austrian Economics”, 24/2 (2011), 141-156. - Miles 2005

M. Miles (2005), Alternative spaces, alternative histories: Revisiting three artist-run initiatives, “Eyeline”, 58 (2005), 25-27. - Mitali, Ingram 2018

Mitali, B. and Ingram, Paul L., Fame as an Illusion of Creativity: Evidence from the Pioneers of Abstract Art, “HEC Paris Research Paper No. SPE-2018-1305, Columbia Business School Research Paper”, (2018), 18-74, accessed 20 February 2021. - Murphy, Cullen 2016

G. Murphy and M. Cullen (2016), Artist-Run Europe - Practice/Projects/Spaces, Amsterdam 2016. - Picard 2009

C. Picard, The Artists Run Chicago Digest, Chicago 2009. - Sperandio 2010

S. Sperandio, La nuova scena indipendente dell’arte milanese: i giovani scelgono il no profit, “Domenca 24”, 14 aprile 2010, accessed 20 February 2021. - Tavano Blessi, Sacco, Pilati 2011

G. Tavano Blessi, P. Sacco & T. Pilati (2011), Independent artist-run centres: an empirical analysis of the Montreal non-profit visual arts field, “Cultural Trends”, 20/2 (2011), 141-166. - Vanzaghi 2019

S. Vanzaghi, Italian Cluster. Un punto sui project space in Italia, “Memecult”, 23 April 2019, accessed 20 February 2021. - Young 2016

R. Young, Why are we saving All these artist publications + Other Galleries stuffs? The Emergence of Artist-Run Culture in Halifax, “Archivaria, The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists”, 82 (2016), 190-193. - Wilczek 2010

E. Wilczek, The role of contemporary artist-run spaces in the UK, “Nottingham Institute for Research in Visual Culture”, 17 Feb 2010.

English abstract

The article focuses on the role and typology of project spaces within the contemporary art system and in particular in the city of Milan. By problematizing the notion of ‘independence’ and the terminology of ‘independent space’ in opposition to ‘project space’, the article investigates how an art space interacts with the system. The objective is twofold: firstly, the research displays the interrelation between project spaces through a network analysis; secondly, it outlines a morphology of project spaces based on similar organizational and managerial models. In the conclusive part the authors identify three main typologies of project spaces of the Milanese scene: the research space, the hybrid space and the proto-gallery.

keywords | project space; contemporary art system; network analysis; independent space.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio.

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo/ To cite this article: Laura Forti, Francesca Leonardi, At the border of artistic legitimation. Geography, practices and models of project spaces in Milan, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 179, febbraio 2021, pp. 209-228. | PDF dell’articolo