The Etruscan and Roman territory of Trequanda (Siena, Italy)

Rediscovering the ancient ‘thermal’ complex of Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano at Castelmuzio

Jacopo Tabolli, Debora Barbagli, Cesare Felici

Abstract

I. Introduction

I.1 The territory of Trequanda between Etruscans and Romans | Jacopo Tabolli.

I.2 The discovery of a ‘thermal’ complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano | Jacopo Tabolli.

II. New data on the “thermal” complex

II.1 Documents in the Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence | Debora Barbagli.

II.2 A “New” Plan for the Thermal Complex at Santo Stefano a Cennano | by Jacopo Tabolli.

II.3 Mapping the new evidence | by Cesare Felici.

III. Conclusions | by Jacopo Tabolli

1 | The territory of Chiusi during Etruscan and Roman times (after Bianchi Bandinelli 1925). The area outlined indicates the region of Trequanda (image by J. Tabolli).

One hundred years after the dissertation of Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli on the Etruscan and Roman territory of Chiusi, looking at the map of the area considered to be directly under the control of the city-state, the municipality of Trequanda marks part of its northern border (Bianchi Bandinelli 1925, pl. 1) [Fig. 1]. Sitting halfway between Val di Chiana, Val d’Asso and Val d’Ombrone, and still characterized by a pluricentric medieval articulation between the villages of Trequanda, Petroio and Castelmuzio, this territory was often considered to be a marginal area within the general understanding of the region of Chiusi in the first millennium BC. Despite Bianchi Bandinelli’s view on the direct control operated by Chiusi on its western territories a traditional low-key consideration on the Chiusine power on this region has prevailed in literature (e.g. Rastrelli 2002). Recently, the work of Valeria Acconcia has once again brought new light on this territory ‘half way’ between Chiusi and Volterra, stressing the role of Chiusi especially in the area of the valley of Ombrone (Acconcia 2012). New studies looking at the power of the city-state in the first millennium, with different degrees of control (Salvi, Tabolli 2020) over its economic resources (Vanni 2023) are constantly stressing the dense network of evidence – satellite sites, necropoleis, and sanctuaries – that defines a consistent strategy in the occupation of the crucial passes operated by Chiusi.

In the area of Trequanda, the sites of Petroio and Castelmuzio and the long ridge between them played a particular role. The valley of the small river Trove constitutes a perfectly oriented east to west corridor that joins Val di Chiana with Val d’Asso [Fig. 2]. We are at the modern border between the municipalities of Trequanda and Montalcino (previously San Giovanni d’Asso) that remains a strategic location still nowadays. In this landscape, the Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano [Fig. 2, no. 1], which is the focus of this contribution, is a Medieval church that occupied the end of this geographical ridge. Situated in a picturesque corner of the Tuscan landscape, in an elongated plateau characterized by secular olive trees, the site is located 400 meters above sea level.

The first mention of the church dates back to the 8th century AD (for a complete bibliography, see Pericci 2021). From the Pieve, the control over the landscape is impressive. From the mountain of Cetona, one can easily see Radicofani and Amiata to the south and the Chianti and Pratomagno to the north, thus controlling the vast majority of the current province of Siena.

This area is characterized by the longue durée life of sites and routes, from Etruscan to Roman times, especially starting from the Late-Archaic and the Hellenistic periods. S. Vilucchi and A. Salvi have published the important fortified site of Piazza di Siena (Vilucchi, Salvi 2008) [Fig. 2, no. 2] that functioned as a stronghold of Chiusi during the Hellenistic period at a time in which the fortification with oppida characterized a large part of ancient Etruria and the entire province of Siena (Tabolli 2021). Excavations demonstrated a possible frequentation also from the Archaic period, from the 6th century BC until the beginning of the 1st century BC. The number of evidence for the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC increased especially in terms of small or medium size necropoleis. Numerous tombs were discovered between 1905 and 1910, in the locality Belsedere [Fig. 2, no. 3] along the river Asso, northwest of Montisi (Paolucci, Minetti 2011; Acconcia 2012, 113, no. 529, with complete bibliography; Paolucci, Salvadori, Turchetti 2016), especially in relation to the famous tomb of Petru with five preserved urns (Maggiani 2016; Turchetti 2018). West and East of Piazza di Siena, the discovery of urns testifies to the presence of small necropoleis in the localities of Collelungo (Acconcia 2012, 112, no. 536, with complete bibliography) [Fig. 2, no. 4] and Badia Sicille (Acconcia 2012, 113, no. 544, with complete bibliography).

2 | The area of Trequanda. Medieval villages are in purple. Numbers in red indicate the ancient sites mentioned in the text (image by C. Felici and J. Tabolli).

The area of Castelmuzio, in the southern part of the territory of Trequanda, reveals the larger amount of evidence. At least two necropoleis have been partially excavated at the beginning of the twentieth century. In the area of “Fondo Perugini” [Fig. 2, no. 6] – the first publication was provided by E. Galli in 1915 (Galli 1915) and a complete bibliography was summarized by V. Acconcia (Acconcia 2012, 113, no. 541, with complete bibliography) and especially around Podere Tomba (Fig. 2, no. 7) (Acconcia 2012, 113, no. 540, with complete bibliography) dated unanimously to the 3rd century BC. In the case of Fondo Perugini, most of the artifacts date to the 2nd century BC, although the urn with the inscription venel spurina dates to the 5th century BC (Cherici 1989, 54: 33), possibly testifying to the long use of the chamber tomb. South of Fondo Perugini another small nucleus of tombs has been identified at Marabicce [Fig. 2, no. 8] (Pistoi 1997, 125). The site of Podere Tomba with its evocative toponym was excavated by Pietro Piccolomini Clementini (Bianchi Bandinelli 1927, 21 no. 2-3), the sienese archaeologist who also owned this land, and the author of the excavation at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano discussed in this contribution. A series of chamber tombs at Podere Tomba, with urns in fetid stone and inscriptions of the Etruscan families titulni and acrnis (Acconcia 2012, 278), dated by R. Bianchi Bandinelli during the 3rd century, but still unpublished (Turchetti 2018, 242). Recently, this area was surveyed by M. Pistoi, who mentioned the possible location of some of the urns in the castle of Rocca d’Orcia (Pistoi 1989, 49; Pistoi 1997, 122-123). Some of these family names also occurred on urns mentioned in the Sloane manuscript at the British Museum recorded in 1552 in the “house of Matteo Salvi”, but coming from Trequanda (Cristofani 1979, 142-143). It should be noted the analogies in the occurrence of these family names at Castelmuzio and the necropolis at San Provenzano-La Ripa, in the territory of Castiglione d’Orcia (Acconcia 2012, 290): both sites are within the land of Piccolomini.

The east-west belt of necropoleis along the fringe between Petroio and Castelmuzio possibly corresponded to the consolidation of an ancient route, controlling this crucial passage in the landscape. Castelmuzio is also at the crossroads of an important north-south route. Still in the 3rd century BC, the presence of a sanctuary at Sant’Anna in Camprena, at Podere Lama [Fig. 2, no. 9], attested by a long inscription mentioning family names of different families (Maggiani 1988), confirms the focal character of this area that was also characterized by a large necropolis in the area of Mensa Vescovile [Fig. 2, no. 10] (Acconcia 2012, 121 no. 603), covering a period that from the Hellenistic times reaches the Empire. Another small votive deposit has been identified at Podere Raguzzi [Fig. 2, no. 11] (Felici 2004, 105-106 no. 51.1).

The full Romanization and 1st century BC transformations represent a smooth transition, possibly with limited events of destruction at the time of the war between Sulla and Marius in the early 1st century BC, as evident at the site of Piazza di Siena [7]. The control over this only apparent peripheral part of land increased during the course of the 1st century BC, under the new administration of the municipality of Clusium (Paolucci 1988a; Paolucci 1988b). The complicated road system between Clusium and Saena Iulia is still under debate, especially decrypting the distances between Ad Novas, Manliana, Ad Mensulas, and Umbro Flumen, of the Peutinger Table (Tabolli 2021). The debate has been focused and ‘stuck’ between two main itineraries. The northern hypothesis (through Montepulciano, Torrita, Sinalunga and Rapolano Terme) was discussed by M. Lopez Pegna (Lopes Pegna 1953, 428) and S. Patitucci Uggeri (Patitucci Uggeri 2009) on one side; on the other one, the southern hypothesis (though Montepulciano, Torrenieri and Buonconvento) was discussed first by G. F. Gamurrini (Gamurrini 1898, 274) and recently, by S. Bertoldi, applying GIS based analyses (Bertoldi 2013). The ongoing excavations at the Etruscan and Roman thermo-mineral sanctuary of Bagno Grande at San Casciano dei Bagni have reopened the question (Carpentiero, Felici 2021) of the primary road corridor between the Val di Paglia and Valdorcia since the high Imperial age, and of its early organization, perhaps as a cursus publicus, considered to be a sign of imperial interest in the area (Vanni 2023). The recent publication of new evidence from Pieve di Corsano at Monteroni d’Arbia (Pericci 2018) and especially the important inscription of a servus attesting the presence of senatorial families in the Julio Claudian period from Romitorio at San Quirico d’Orcia confirm the existence of a denser series of crossroads at least during the time of Claudius (Lazzeretti 2023).

Moving back to our area of interest, recently the presence of a Roman Villa has been pointed out along the river Trove, to the south-east of Castelmuzio, in the locality Molino di Trove [Fig. 2, no. 10] (Della Giovampaola, Pericci, Sordini 2019). The site has been identified during aerial survey and field survey campaigns, and after rescue excavations. Although preliminary, data reveal a large site on one of the terraces along the river, thus suggesting a dense network of evidence for the Roman Imperial period in the area. It is important to stress that the river Trove is also characterized by a number of thermo-mineral springs. In the area of Bagnacci [Fig. 2, no. 12], southwest of Castelmuzio, a thermo-mineral (located along the so called Rapolano-Trequanda ridge) complex functions, not far from Sant’Anna in Camprena. Other areas with hydrothermal presence are known at Podere Miciano (east of Trequanda) [Fig. 2, no. 13] and along the Borro delle Solforate [Fig. 2, no. 14], close to Petroio. In the geological maps of the territory, the area of Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano is also mentioned for its thermo-mineral waters, although with the exception of a travertine basin preserved into the Romanic church, no evidence appears on the ground of a possible thermal spring.

J.P.

I.2 | The discovery of a “thermal” complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano

In 1927 Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, while publishing the volume on the Montepulciano area in the series “Archaeological Map of Italy”, described a Roman archeological site at “Castelmuzio, Pieve di Santo Stefano, in the Province of Siena, Municipality of Trequanda” (Bianchi Bandinelli 1927, 21 no. 1):

Ruins of Roman thermal baths “really similar to those found by Piccolomini in Siena at Bozzone” that appeared during agricultural works around the year 1900. Bricks, fragments of mosaics and one fragment of wall-painting. 1st to 2nd centuries of the Empire. In the properties of Piccolomini Cinughi. Artifacts found are preserved in Siena at the Museum Piccolomini. Unpublished.

Although Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli mentioned that the site was discovered during cultivations in the land owned by the “Piccolomini – Cinughi de’ Pazzi” family, and that the artifacts discovered where later displayed at the “Museo Piccolomini”, and notwithstanding the direct comparison suggested between this site and the Roman thermal complex at Pieve al Bozzone “found by Piccolomini”, for unknown reasons R. Bianchi Bandinelli did not mention the excavator of the early 1900 research at Castelmuzio: the archaeologist Pietro Piccolomini Clementini (Barbagli, Tabolli 2022; Barbagli, Tabolli 2023, 13-38). This omission of the name of P. Piccolomini by R. Bianchi Bandinelli is not uncommon. We have recently outlined that in the entire series of publications for the Carta Archaeologica, R. Bianchi Bandinelli, despite pointing out the references to the Museo Piccolomini, did not stress his intellectual debt towards the work of P. Piccolomini. The vast majority of sites discussed by R. Bianchi Bandinelli, especially concerning the territory close to Siena, is indeed based on the information collected between 1893 and 1907 by P. Piccolomini, and on sites that he had directly surveyed or excavated, including objects purchased by Piccolomini for his Museum (Barbagli, Tabolli 2022). The unfortunate dismemberment of the “Museo Piccolomini” at Palazzo del Capitano following the death of his widow, Marianna Cinughi de’ Pazzi, and of their only daughter Pierina Piccolomini Clementini in 1962, consisted in the division between the five heirs of the entire archaeological collection, that was unfortunately not protected by a single archaeological decree at that time, and for a long time considered lost (Barbagli, Tabolli 2023).

In parallel to the loss of the Collection, it seems that in archaeological literature the exact location of the ‘thermal’ complex discovered close to the Pieve di Santo Stefano at Castelmuzio was lost too. All publications that mentioned this site referenced only the few lines described in 1927 by Bianchi Bandinelli, as is the case of the Atlante dei siti archeologici della Toscana edited by Mario Torelli (M. Menichetti in Torelli 1992, 335) and the Archeologia in Valdichiana by Giulio Paolucci, to mention the most important ones (Paolucci 1988a, 68). From the same area “in quibus pars balneorum detecte est” (CIL 07242) in 1907 a marble funerary headstone with inscription was found and said to belong to the properties of Emilio Ciani: it appeared on the Corpus Iscritionum Latinarum in 1926, published by E Bormann. The inscription belongs to the series of funerary inscriptions “optime de se meritate”, possibly related to the presence of a libertus and is preserved in four fragments. Slightly modifying the publication by C. Gabrielli, the inscription reads (Gabrielli 2020, EDR 158187):

D(is) [M(anibus)]

Sad[- - - ae?]

T(itus?) Sa[ - - -us?]

Lib[- - -] 5 - - - - - -

- - - - -

[op]time [de se]

merita[e - - -]

E. Bormann based the CIL publication of the inscription on the apograph by R. Egger. However, in 1926 the fragments were already lost. The 1907 date of discovery coincides with the year of death of P. Piccolomini for scarlet fever, when he was only 27 years old (Barbagli, Tabolli 2022). As we will discuss further on, the land surrounding the Pieve had previously belonged to the family of P. Piccolomini, as recorded also by R. Bianchi Bandinelli, and probably came from Piccolomini’s wife M. Cinughi de’ Pazzi. The land was sold to the Ciani family prior to Pietro’s death, therefore the circumstance of the discovery of the inscription is associated with the new owner in R. Bianchi Bandinelli’s account.

No archaeological research was undertaken in the area surrounding the Pieve until the early 2000, when under the direction of Silvia Vilucchi from the Superintendency of Archaeology of Tuscany, the area of Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano was surveyed (the operations on the field were carried out by Ada Salvi) in light of the project of developing the plan for the archaeological municipal museum of Pienza that, once opened, would have hosted a section on the territory. Nevertheless, the museum has never opened. In 2002, within the framework of the landscape studies promoted by Riccardo Francovich and carried on in this area by Cristina Felici (Felici 2008), ten topographic units with concentration of fragments have been isolated during the surveys of 2003, and related to a Roman villa, with finds dating from the Late Republican period to the Late Antiquity.

The area has also been included in the geophysical studies on this region by F. Pericci, but no new surveys were conducted at this time, because the discovery and subsequent rescue excavations at the Roman thermal site of Pian del Molino di Trove, located 2 km to the south east constituted the focus of the research (Pericci 2021; Della Giovampaola, Pericci, Sordini 2019). Despite this new season of research, the exact location of the thermal complex and its characteristics remained based only on R. Bianchi Bandinelli’s description.

J.T.

II. New data on the “thermal” complex

II.1 | Documents in the Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence

In the Historic Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence a folder is preserved, containing documents listed “Siena. Pietro Piccolomini. Ruderi antichi in Comune di Trequanda in terreno E. Ciani” (transl: Siena. Pietro Piccolomini. Ancient Ruins in the Municipality of Trequanda in the land owned by E. Ciani). The folder contains a group of six letters and postcards, written by P. Piccolomini, Luigi Adriano Milani, at the time director of the Etruscan Museum of Florence and Emilio Ciani, an engineer and agronomist to which the land surrounding the Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano belonged at the time of the discoveries. Despite the mention of R. Bianchi Bandinelli in 1927 (Bianchi Bandinelli 1927, 21 no. 1), the properties of the Podere Pieve belonged to Emilio Ciani since 1903, when - as the agronomist wrote to the director Milani (letter dated September, 19th, 1906 [Historic Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence F21, September, 19th, 1906]) - he bought this part of territory near Castelmuzio. Actually, this land had been previously part of the vast possessions of the family Piccolomini (Consorteria Piccolomini), as Pietro himself specified in a letter on February, 14th, 1906 [Historic Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence F21, February, 14th, 1906]. Castelmuzio was placed under the jurisdictional law of Andrea Piccolomini in 1470, (Repetti 1972, 565-566; Cammarosano, Passeri, Guerrini 2006). It must be therefore underlined that the young count Piccolomini knew this part of the Sienese territory, because of the many properties that his family had administered in Val d’Asso, Asciano, Trequanda (Barbagli, Tabolli 2022).

As already pointed out, during agricultural works, ruins of walls, bricks and mosaic floors were discovered. In a letter sent to the director Milani and dated February, 14th, 1906, Pietro Piccolomini provided few details about these discoveries, his involvement and intervention, together with information about his ‘pioneering’ approach to the archaeology of territory. When Piccolomini was informed of the discoveries of ruins of walls, fragments of opus signinum and opus tessellatum, he undertook at his own expense “excavations in order to understand if the discovered artifacts were connected” [Historic Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence F21, February, 14th, 1906]. As it was confirmed by the continuation of research on the field, the discoveries could belong to a “quite sumptuous Roman Villa” with thermal baths. The few artifacts, including fragments of painted walls, were at the time stored in Ciani’s house. Piccolomini asked the director if he suggested continuing with the excavations “not with the hope to discover important artifacts, but with the only aim to find as much as possible the plan of the building”.

In his answer, dated February, 22th, 1906, Milani asked Piccolomini to write a brief article for the journal Notizie degli Scavi including a plan “with the task to make the article more interesting” [Historic Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence F21, February, 22th, 1906]. We do not know why this was never published in Notizie degli Scavi, where the tombs of Fondo Perugini were published in 1915 (Galli 1915).

Despite the absence of a final publication, an important sketch with the plan of the excavations, probably made by the new owner Emilio Ciani, is conserved in the folder of the Archive. Together with the plan, the last documents testify to the correspondence between Luigi Milani and Emilio Ciani: in the letter dated September 1906 [Historic Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence F21, September, 19th, 1906] the agronomist expressed his will of ending the archaeological excavations because of the economic costs. Ciani mentioned an “attached sketch” concerning the excavations that “occupy a larger space than the one included in the sketch”.

According to the documents preserved in the Archives in Florence, this is the last archive report that we have about the discoveries in Podere Pieve near Castelmuzio. Before examining the plan, some aspects concerning the approach of Pietro Piccolomini on archaeological investigations and on the knowledge of the territory can be pointed out. As we mentioned, the territory near Trequanda belonged to the Piccolomini family for a long time and the willness to discover and preserve the history of the territory characterized the entire life of P. Piccolomini. The interest of the youth count seems to be concentrated on the publishing of his family’s archaeological collection and on the archaeological excavation in his properties at Pieve al Bozzone (years 1893/1899) (Piccolomini 1899). After 1900, P. Piccolomini was involved in historical and archeological publications concerning Siena and its territory (1901-1905), with the partial exception of Castelmuzio, where the count undertook archaeological research. The interest on the area of Val d’Asso appears indirectly in other documents: Pietro Rossi, a professor of Institution of Roman law at the University of Siena and an important member of the Sienese cultural context at the end the the 800s / beginning of the 900s (Bracci 1931), wrote the necrology for P. Piccolomini, stressing that at the moment of his death he was going to prepare new publications “on important Etruscan-Roman archaeological excavations from Val d’Asso and Val d’Orcia, by the same count with competence discovered and undertaken” (Rossi 1907).

The epistolary correspondence with Luigi Milani also documents the relationship between the director and the Sienese Count. It is not the first time that Milani leans on him. In 1903, for example, Pietro informed Milani about the demolition of the Tower “del Pulcino” in Siena and the discoveries of sporadic artifacts, such as common ware and black glazed fragments (Barbagli, Tabolli 2022, 363). The friendly relationship between the two of them is also testified by the above cited letter: before the conclusion, Piccolomini invited Milani to come to Siena and visit his museum “where he will find some news”. Milani was therefore aware of the important collection put together in Piccolomini’s villa at Santa Regina, near Siena. It is perhaps the death of Count Piccolomini in 1907 that prevented him from concluding his study on this area of the Sienese territory, to which he was deeply tied and in which he was deeply interested.

D.B.

II.2 | A “New” Plan for the Thermal Complex at Santo Stefano a Cennano

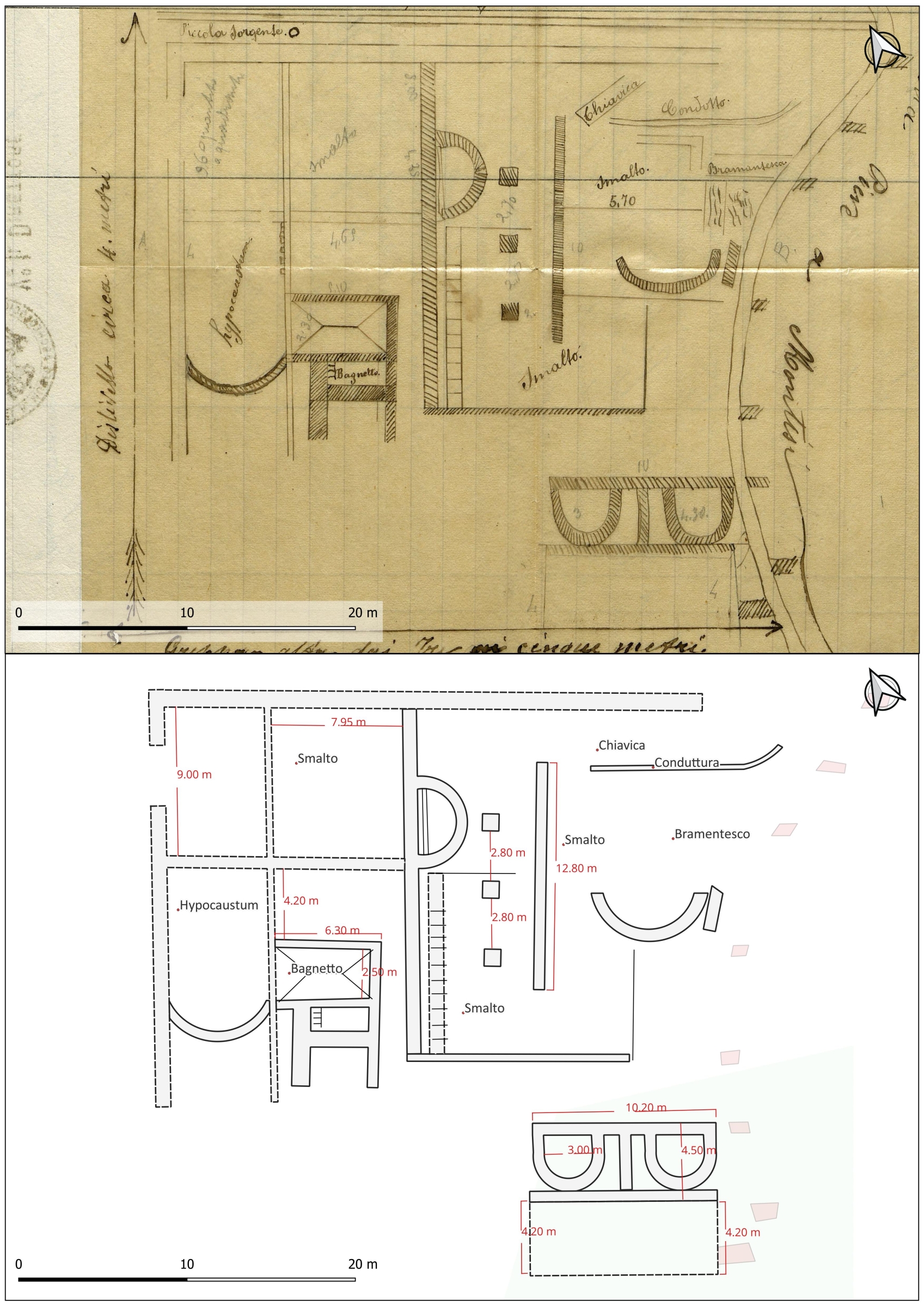

3 | Map of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano (courtesy of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze, Direzione Regionale Musei della Toscana).

4 | Wall numbers on the map of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano (image by J. Tabolli).

On the final page of the documents a pencil drawn plan of the thermal complex is hand drawn probably by Ciani, on a 1:200 scale [Fig. 3]. An arrow to the left of the plan possibly indicates the north with a “height difference of approximately 4 meters”, thus suggesting a north to south slope. A curved dirt road descends north to south in the right part of the plan, labeled as “via dalla Pieve a Montisi”. Ancient walls appear both to the west and to the east of the road, although it looks as if only the western part of the complex had been excavated. To the northeast of the road, the Pieve, with the characteristic Romanic three apses, and a Podere are represented. As we will discuss further the dimensions of the Pieve and Podere as they appear in the plan are certainly out of scale, as the Pieve and the Podere appear extremely small. The road continues to the north towards Montisi, historically under San Giovanni d’Asso and currently Montalcino, outside the area of the Municipality of Trequanda.

The Bath Complex appears to be located between two different areas. To the north, an area identified as a “Plateau of Tombs” is separated from the area with structures by a “Fence of the Bath”. To the very south, an horizontal arrow indicates a “three to five meters terrace” (“greppa” in Italian). The presence of tombs to the north of the “bath complex” is confirmed by the 1907 discovery of the abovementioned funerary inscription. We assume that “fence of the Bath” may refer to an ancient longitudinal external wall. Immediately to the south of the “fence”, a circle indicates a “small spring”, possibly serving the entire complex.

South of the spring a large rectangular wall [Fig. 4, no. 1-2] presents an opening close to its north western corner, possibly an entrance. It is the thicker wall represented on the plan and it may correspond to the perimeter wall of the complex. It is important to outline how some walls on the plan are blank while others are filled in with diagonal lines, possibly suggesting different techniques or preservation conditions, as we will discuss further on.

Looking at the plan of the complex as a whole, we observe a possible central partition represented by a large north to south wall [Fig. 4, no. 12]. To the west of it, three walls [Fig. 4, no. 5-6, 3] represent a partition of spaces. A label “smalto”, possibly referring to a plastered floor characterizes an area (between the walls in [Fig. 4, no. 1, 5-6, 12]), while an elongated room with a southern apse (between the walls in [Fig. 4, no. 2, 3, 5, 4]) is identified as a “hypocaust”. Small square elements along the eastern wall may represent pipes. Immediately to the east, a first room (between walls [Fig. 4, no. 5, 7, 6, 12]) appears to have an opening to the southeastern corner. A second and smaller room (between walls [Fig. 4, no. 5, 7, 8, 9]) has a peculiar representation of the floor, possibly identifying sloping surfaces. South of this room, a “small bath” (“bagnetto” in Italian), (between walls [Fig. 4, no. 9, 8, 11, 10]) is represented with two steps along the western wall.

5 | Excavation photograph of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano (courtesy of Ferruccio Malandrini - photographic collection).

6 | Comparison between the map of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano and the excavation photograph (image by J. Tabolli).

Moving to the east of the central wall [Fig. 4, no. 12] we observe an apse [Fig. 4, no. 13] and a large corridor with three pillars [Fig. 4, no. 15, 16, 17]. The area is closed to the south with what looks like a thinner wall [Fig. 4, no. 14]. Parallel to the longitudinal wall [Fig. 4, no. 12] is a line filled with small squares [Fig. 4, no. 18] that marks the eastern space that was plastered. It is unclear if the wall that constituted the eastern side of the portico [Fig. 4, no. 19] was only partially preserved or if it did not reach on purpose the northern perimeter wall [Fig. 4, no. 1] and the southern wall [Fig. 4, no. 14], thus allowing for a passage. The space between this sector and the road appears more confusing on the plan in terms of alignments. A diagonal “sewage canal” is drawn to the north west [Fig. 4, no. 20] (labeled “chiavica” in Italian), close to a “pipe” [Fig. 4, no. 21] (labeled “condotto” in Italian); a central area presents once again a plastered floor, located between the angle of a wall [Fig. 4, no. 22] and a second apse to the south [Fig. 4, no. 25]. The orientation of a wall to the east of the apse is unclear [Fig. 4, no. 26]. Similarly, pencil lines, similar to small ‘waves’ [Fig. 4, no. 24], reached to the north a horizontal “bramantesca”, which is an archaic word in Italian for “sloping surface” or “barrier” [Fig. 4, no. 23].

7 | Detail of the mosaic visible on the excavation photograph of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano (courtesy of Ferruccio Malandrini - photographic collection).

The plan also displays the southern sector of the complex, along the western side of the road. Two parallel east-to-west walls [Fig. 4, no. 27, 29] define two apses [Fig. 4, no. 30, 31], also separated by a north to south wall [Fig. 3, no. 28]. It should be noted that the northern wall [Fig. 4, no. 27] is the only one that continues [Fig. 4, no. 38] directly to the east of the road, while the others [Fig. 4, no. 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39] appear possibly as schematic notes on the presence of other walls, although some are possibly aligned [Fig. 4, no. 33 to 1; 37 to 14]. Another rectangular space (4x10m) appears to the south, before the location of the terrace interrupts the sequence (with undefined small walls continuing across the road, such as [Fig. 4, no. 32 and 39]). This invaluable plan demonstrates the articulation of spaces but its interpretation remains highly problematic. A fundamental help to unlock the plan probably drawn by Ciani and to give evidence to the complex came unexpectedly from a sienese collector of photographs, Ferruccio Malandrini. Among four photos labeled “Piccolomini” we were able to identify in November 2023 one image of the 1900 excavations of the complex [Fig. 5]. The photo portrays an excavation scene with eight people. The three figures to the left are currently excavating, two men are standing in the center, while three men are at a higher elevation to the back, along the slope. The young man in the center of the image, partially leaning on a wall, is certainly P. Piccolomini.

We should situate the photo prior to the time in which the ground plan was drawn, because some walls are only partially exposed [Fig. 6] and the workers are still excavating the room labeled in the plan as “hypocaust”. The photo was taken from the south-eastern corner of the “small bath” (“bagnetto”), (between walls [Fig. 4, no. 9, 8, 11, 10]). It is evident the plastering of this small space with the two high steps on the western side. The room immediately to the north (between walls [Fig. 4, no. 5, 7, 8, 9]) has a white mosaic floor [Fig. 7], as the representation visible on the drawing. This room is the ‘protagonist’ of the photo as all the people are gathered around and Piccolomini is standing in front of it. Possibly the discovery of the mosaic attracted the viewers.

There are a few discrepancies between the photograph and the plan that are worth mentioning, because they illuminate possible small mistakes of the plan. In the case of the bagnetto, while on the plan this seems to be aligned with the mosaic room (through wall Fig. 4, no. 8]), the photo reveals that the space of the small bath is actually smaller (as in [Fig. 6]). Similarly, the photo reveals a very large structure, north of the mosaic room (wall [Fig. 4, no. 7]) that is located at a higher elevation and presents a semicircular section, partially cut on its southern edge. Although no bricks are visible in the photo and it could be built in opus caementicium, this structure does not appear in the plan. One could argue that Piccolomini interpreted this evidence as a later element in the area and therefore did not represent it on the plan. It is also possible that there is a wrong drawing on the plan of the large central wall [Fig. 4, no. 12] although we tend to exclude this possibility. Considering the proximity of the calidarium, one could argue that we are facing part of the praefurnium of the structure.

J.T.

II.3 | Mapping the new evidence

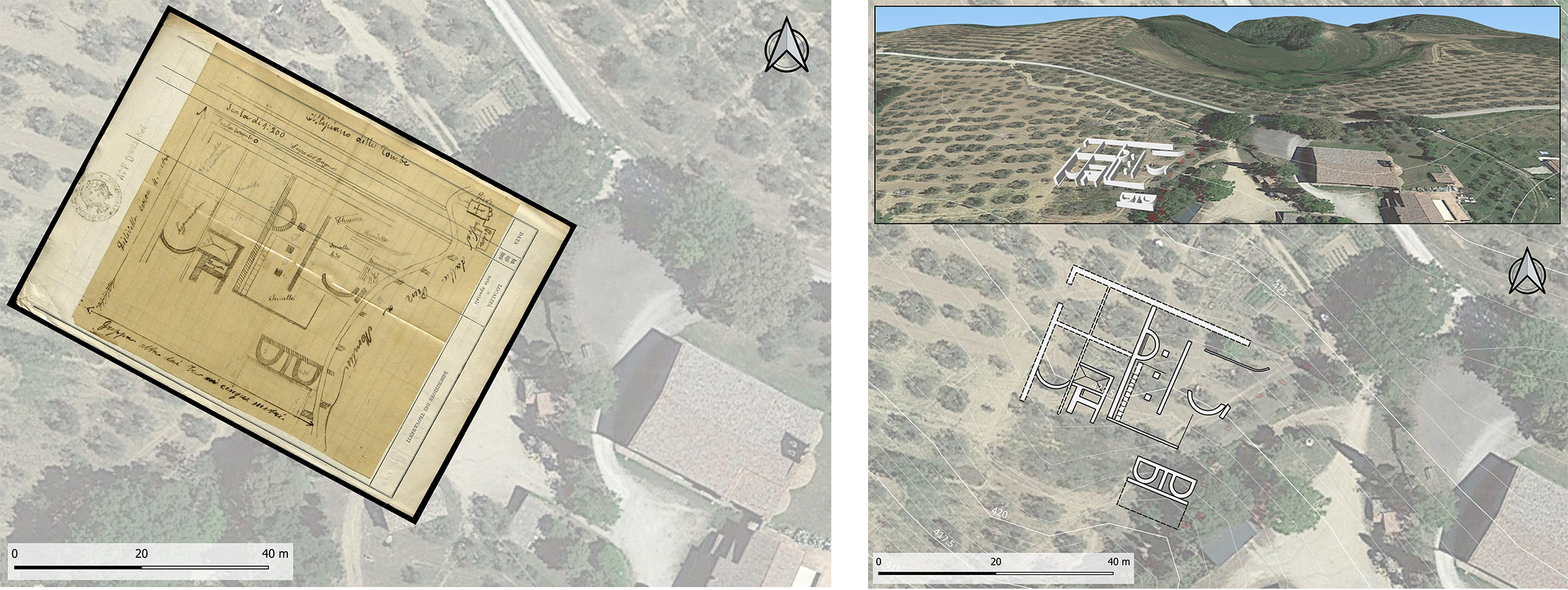

8 | Digitization of the map of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano (image by C. Felici).

The plan made by Ciani in 1906 was georeferenced inside a GIS platform, using open source QGis 3.30.3. The digitization of the plan has allowed us to anchor it to the Cadastral Map of 1820, using especially the north to south road “via dalla Pieve a Montisi”. Comparing the scale of the drawing by Ciani with the cadastral map, it is clear that the dimensions of the Pieve and the “Podere” represented are out of scale, and functioned as a generic identification of the location of the archaeological complex, when compared to the street and the church. This building probably was meant to serve as a spatial reference of the excavation area and to provide landmarks.

The second element that proved to be fundamental for the localization of the site has been the artificial cliff represented on the lower part of the plan. This cliff has been identified on the field and is visible on the orthogonal photo of the area (2019). Maintaining the 1:200 scale based on the assumption that the measures, also recorded close to each section of the walls and for the pillars, are accurate – Ciani was an agronomist – we were able to project an overlay on the cadastral map and on the 2019 orthogonal photo. Thanks to the metric references written on the plan, it was possible to import the drawing into the GIS platform on the basis, not of geographical and spatial parameters, but of the metric data reported by the author. The resulting map is metrically correct within the GIS project [Fig. 8]; thus the ancient structures were digitized, giving a .shp file which is a more manageable version than the GeoTIFF image. In this way the creation of a digital map can help to speculate on the correct location of the buildings. The comparison between the two base-maps demonstrates that an error of approximately two meters exists between the cadastral map and the satellite images.

Analyzing Ciani's plan, we became aware of two important indications given by the author on the top and bottom of the structures; in fact, on the top the presence of the “altopiano delle tombe” (the plateau of the tombs) is indicated, while on the bottom there is a drop in elevation due to “Greppa alto dai tre ai cinque metri” (a cliff three to five meters high). These indications allowed us, after an in situ survey (January 2024), to locate the thermal complex approximately 49 m northwest of the Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano, within an olive grove in the southern part of which an elevation difference ranging from 2.50 m to 3.50 m is still visible [Fig. 9]. According to this geo-referenced plan, the ancient structures would have had the same orientation as the Pieve and would occupy an area of approximately 1500 square meters. Naturally enough, this contribution does not presume to geo-localize the excavation carried out by P. Piccolomini with a centimetric accuracy, but to try to hypothesize the location of the complex and to reconstruct the landscape and environmental context with which it relates today. What has been obtained is therefore a starting point for planning future field research aimed not only at relocating the ‘thermal’ complex, but also at gaining a better understanding of how this landscape must have looked in ancient times, which is likely to have seen the presence of other structures and a road system [Fig. 10].

C.F.

III. Conclusions

The analysis of the discovered plan and photograph has finally given concrete evidence to the 1927 short description by R. Bianchi Bandinelli (Bianchi Bandinelli 1927, 21 no. 1). The identification of the precise location of the site and the projection to the ground of the plan leads to an understanding of the dimensional characteristics of this complex. We can argue that the area lies on the southern slope of the plateau where the church is located; the church itself possibly was built on the top of earlier Roman structures located on the summit of the plateau, thus suggesting the existence of different terraces in the area and their consistent use. Although the information combining the plan and the photograph does not allow for a complete reading of the complex, we should imagine that the room to the west, with the southern apse functioned as a calidarium. The “small bath” with steps to descend could have also functioned as a reservoir for water. Highly problematic remains the distinction between ways in which walls are represented. As an hypothesis, we can suggest that walls filled with diagonal lines represent parts of structures preserved only at the foundation level, while the outlined ones are actual walls preserved in some height. This could be proved by the photograph [Fig. 5]. This reading of the ways in which Ciani differentiated the walls in the plan could also explain the small ‘closed’ apses [Fig. 4, no. 13, 30 and 31]. If their function was to be small pools, similarly to many cases of baths with small ‘individual’ pools around the larger spaces, these could have appeared closed at the foundation level and then opened in the actual wall (only at the apses).

Based on the photograph, the outlined walls are all in opus latericium while the ones filled with diagonal lines are all cut at the floor level. The opus latericium is not particularly elegant in the shapes of the bricks and it looks as if only inside the calidarium the walls were also plastered. The painted fragment recorded in E. Ciani’s letters [Historic Archive of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence F21, September, 19th, 1906] and in R. Bianchi Bandinelli’s publication (Bianchi Bandinelli 1927, 21 no. 1) is not visible in the photograph. Foundations are visible in the case of wall in [Fig. 4, no. 2] and consist of smaller bricks. At the foundation level of wall [Fig. 4, no. 3] a rectangular space is opened, possibly functioning as an air access. The most problematic part of the comparison between the plan and the photograph remains the vaulted structure visible in the photograph, ending where wall [Fig. 4, no. 6] is represented on the plan. We could argue that the possible identification as a cistern can be related to the “small spring” immediately identified to the north of this room, as it is visible on the plan. If this structure was indeed a praefurnium it would have been aligned to the calidarium.

Looking at the complex as a whole we can certainly note the complexity of the plan with the articulation in different areas, possibly at different elevations, with pools concentrated to the west and the east of the long wall [Fig. 4, no. 12]. Passages are granted at least where the corridor covered by pillars was located.

The major problem remains the identification of the type of complex. With the absence of any data on the topography of the ancient structures around it, it is difficult to determine if we are facing a Roman Imperial villa with annexed baths or a thermo-mineral complex, such as a small spa, considering the possible presence of springs with thermal water in the vicinity. The presence of areas with squared pipes in the room that Ciani identified as “hypocaustum” and possibly a calidarium, suggests that water was artificially warmed at the site. In this perspective the small spring visible on the map and currently invisible on the field could have been a cold spring. Mixed complexes with thermo-mineral and artificially warmed water existed (Bassani, Fusco, Bolder-Boos 2019) and the evidence is from the plan and photograph are too limited to ascertain a specific function.

A major result of this study is to clarify a second important excavation by P. Piccolomini after the campaigns at Pieve al Bozzone (Piccolomini 1899). Once more, the role of this sienese archaeologist at the beginning of the Twentieth century appears fundamental for the understanding of Romanization in the province of Siena. The complex on-going project of locating and documenting the dispersed artifacts once at the Museo Piccolomini (Barbagli, Tabolli 2023, 13-38) will hopefully provide new evidence for the understanding of this complex. New surveys and excavations will target the site to understand how the structures on this terrace functioned compared to the ancient road system and if we are dealing with a large complex similar to a statio or a smaller villa with baths. In anycase, the plan drawn by Ciani and the photograph portraying Piccolomini are finally placing this site on the maps of the Etruscan and Roman territory of Trequanda, at the time of passage between the Etruscan city-state of Chiusi and the Roman municipium of Clusium.

J.T.

9 | Overlay of the map of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano on the 2019 Orthophoto (image by C. Felici).

10 | Hypothesis of the location of ancient structures of the Archaeological Complex at Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano on the 2019 Orthophoto (image by C. Felici).

We would like to thank our friends and colleagues with whom we have discussed our research during the preparation of this contribution; and in particular, Davide Amendola, Giovanni Altamore, Barbara Arbeid, Maddalena Bassani, Laura Bonelli, Giuseppina Carlotta Cianferoni, Chantal Gabrielli, Mario Iozzo, Ferruccio Malandrini, Francesca Mencarelli, Francesco Pericci, Ada Salvi, Edoardo Vanni.

Bibliography

- Acconcia 2012

V. Acconcia, Paesaggi etruschi in terra di Siena. L’agro tra Volterra e Chiusi dall’età del Ferro all’età romana (BAR International Series. African Archaeology 2422), Oxford 2012. - Barbagli, Tabolli 2022

D. Barbagli, J. Tabolli, L’archeologia dell’Etruria e il senese Pietro Piccolomini: attorno a un inedito compendio di antichità etrusche, in A. Piergrossi, A. Babbi, M. Cultraro (eds.), Tra protostoria e storia: l’Etruria nel cuore del Mediterraneo. Scritti in onore di Filippo Delpino per il suo 80o compleanno. Supplemento a “Mediterranea. Rivista annuale di archeologia dell’Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale”, Rome 2022, 347-379. - Barbagli, Tabolli 2023

D. Barbagli, J. Tabolli, Il Museo Archeologico Numismatico di Pietro Piccolomini nel Palazzo del Capitano: tre cartoline da Siena etrusca e romana, in M.E.Garcia Barracco (ed.), Saena Julia. Nuovi contributi per lo studio di Siena in epoca romana, Roma 2023, 13-38. - Bassani, Fusco, Bolder-Boos 2019

M. Bassani, U. Fusco, M. Bolder-Boos (eds.), Rethinking the Concept of ‘Healing Settlements’: Water, Cults, Constructions and Contexts in the Ancient World, Oxford 2019. - Bertoldi 2013

S. Bertoldi, Spatial calculations and archaeology: roads and settlements in the cases of Valdorcia and Valdarbia (Siena, Italy), “PostClassical Archaeologies” 3 (2013), 89-115. - Bianchi Bandinelli 1925

R. Bianchi Bandinelli, Clusium. Ricerche archeologiche e topografiche su Chiusi e il suo territorio in età etrusca, Roma 1925. - Bianchi Bandinelli 1927

R. Bianchi Bandinelli, Edizione della Carta Archeologica d’Italia al 100.000. Foglio 121 (Montepulciano), Firenze 1927. - Bracci 1931

M. Bracci, Pietro Rossi, “Bullettino Senese di Storia Patria” II (1931), 173-186. - Cammarosano, Passeri, Guerrini 2006

P. Cammarosano, V. Passeri, M. Guerrini, I castelli del senese. Strutture fortificate dell’area senese grossetana, Siena 2006. - Carpentiero, Felici 2021

G. Carpentiero, C. Felici, Topografia e indagini non invasive dell’area del Bagno Grande: ricostruzione della viabilità storica e del paesaggio antico di età romana, in E. Mariotti, J. Tabolli (eds.), Il santuario ritrovato. Nuovi scavi e ricerche al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2021, 131-143. - Cherici 1989

A. Cherici, La necropoli di Casalta in Val di Chiana e un'iscrizione romana da Arezzo. Nuovi dati sugli Spurinnae?, “Atti e Memorie dell’Accademia toscana di Scienze e lettere ‘La Colombaria’” LIV (1989), 11-50. - Cristofani 1979

M. Cristofani (ed.), Siena Le origini: testimonianze e miti archeologici (catalogo della mostra Siena, dicembre 1979 - marzo 1980), Firenze 1979. - Della Giovampaola, Pericci, Sordini 2019

I. Della Giovampaola, F. Pericci, M. Sordini, Fotografia aerea e tutela del patrimonio archeologico: il caso della villa romana in località Molino di Trove, “Bollettino di Archeologia On line Direzione Generale Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio”, X, 3-4 (2019), 97-108. - Felici 2004

C. Felici, Carta archeologica della provincia di Siena. Volume VI, Pienza, Siena 2004. - Felici 2008

C. Felici, Processi di trasformazione dell’insediamento rurale tra V e VIII secolo d.C. nella provincia senese. Un esempio di sinergia fra ricerca archeologica e fonti documentarie, Scuola di dottorato Riccardo Francovich, XVIII ciclo, Università degli Studi di Siena 2008. - Galli 1915

E. Galli, Castelmuzio, “Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità” (1915), 267-269. - Gamurrini 1898

G.F. Gamurrini, Sinalunga, “Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità” (1898), 271-276. - Lazzeretti 2023

A. Lazzeretti, Agrippina Minore e l’ager Clusinus: una nuova attestazione epigrafica, “Erga-Logoi” 11 (2023), 177-228. - Lopes Pegna 1953

M. Lopes Pegna, Saggio di bibliografia etrusca, Firenze 1953. - Maggiani 1988

A. Maggiani, Cilnium gens: la documentazione epigrafica etrusca, “Studi Etruschi” 54 (1988), 171-190. - Maggiani 2016

A. Maggiani, I petru di San Quirico e di Trequanda e i cusu di Cortona, “Annuario Accademia Etrusca di Cortona” XXXV (2016),369-385. - Rastrelli 2002

A. Rastrelli, Per una definizione della città nell’Etruria settentrionale ‑ Chiusi e la Val di Chiana, in M. Manganelli, E. Pacchiani (eds.), Città e territorio in Etruria. Per una definizione di città nell’Etruria settentrionale, Atti delle Giornate di Studio (Colle di Val d’Elsa, 12-13 marzo 1999), Siena 2002, 213-236. - Repetti 1972

E. Repetti, Dizionario geografico fisico storico della Toscana, Firenze 1972. - Rossi 1907

P. Rossi, Pietro Piccolomini Clementini, “Rassegna d’Arte Senese” (1907), 108-110. - Paolucci 1988a

G. Paolucci, Archeologia in Valdichiana, Roma 1988. - Paolucci 1988b

G. Paolucci, I Romani di Chiusi, Roma 1988. - Paolucci, Minetti 2011

G. Paolucci, A. Minetti, Gli Etruschi nelle Terre di Siena. Reperti e testimonianze dai Musei della della Valdichiana e della Val d’Orcia, Catalogo della Mostra (Iseo, maggio-luglio 2011), Montichiari 2011. - Paolucci, Salvadori, Turchetti 2016

G. Paolucci, E. Salvadori, M.A. Turchetti, La Collezione Pallavicini a Trequanda, Chiusi 2016. - Patitucci Uggeri 2009

S. Patitucci Uggeri, La viabilità tra Siena e la Via Cassia nella tabula Peutingeriana, in C. Marangio, G. Laudizi (eds.), Studi di topografia antica in onore di Giovanni Uggeri, Galatina 2009, 373-380. - Pericci 2018

F. Pericci, Carta archeologica della provincia di Siena. Volume XIII, Monteroni d’Arbia, Siena 2018. - Pericci 2021

F. Pericci, Indagini multiscalari dei paesaggi archeologici tra la val d’Asso e Trequanda, Scuola di dottorato Riccardo Francovich, XXVI ciclo, Università degli Studi di Siena 2021. - Piccolomini 1899

P. Piccolomini, Terme romane presso Siena, “Bullettino Senese di Storia Patria” VI (1899), pp. 3-65. - Pistoi 1989

M. Pistoi, Guida archeologica del Monte Amiata, Siena 1989. - Pistoi 1997

M. Pistoi, Guida archeologica della Val d’Orcia, San Quirico d’Orcia 1997. - Salvi, Tabolli 2020

A. Salvi, J. Tabolli, Spazi del potere ai confini di Chiusi: nuovi dati sulle “residenze” aristocratiche, “Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’” 27 (2020), 519-571. - Tabolli 2021

J. Tabolli, From Coins to Landscape: Contextualizing Archaeological Perspectives around Roman Siena, in L. Holland Goldthwaite (ed.), Treasure of Chianti: Silver Coinage of the Roman Republic from Cetamura, Livorno 2021, 29-42. - Torelli 1992

M. Torelli (ed.), Atlante dei siti archeologici della Toscana, Roma 1992. - Turchetti 2018

M.A. Turchetti, I caini di Cretaiole (Pienza), “Studi Etruschi” 81 (2018), 219-252. - Vanni 2023

E. Vanni, Potere e marginalità. Ancora sul paesaggio tra economia, sacro e mobilità, in E. Mariotti, A. Salvi, J. Tabolli (eds.), Il santuario ritrovato 2. Dentro la Vasca Sacra. Rapporto Preliminare di Scavo Al Bagno Grande di San Casciano dei Bagni, Livorno 2023, 395-411. - Vilucchi, Salvi 2008

S. Vilucchi, A. Salvi, L’oppidum etrusco di Piazza di Siena a Petroio di Trequanda, in La città murata in Etruria, Atti del XXV Convegno di Studi Etruschi ed Italici (Chianciano Terme-Sarteano-Chiusi, 2005), Pisa-Roma 2008, 389-400.

This paper discusses ‘new’ and fundamental evidence for the understanding of the Etruscan and Roman landscape in the area of Trequanda, Castelmuzio (province of Siena, Italy). This Medieval village is located in the northern area of the territory that during the first millennium BC was under the control of the Etruscan city-state of Chiusi and later of the municipium of Clusium. We discuss the discovery of a plan and a photograph of a Roman ‘thermal’ complex in the locality of Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano. This site was previously known only thanks to a few lines by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli in 1927. It is now possible to position the site accurately on a GIS-based platform and to reconsider the entire topography of the area, which appears crucial both in Etruscan and Roman times.

keywords | Trequanda; Pietro Piccolomini Clementini; Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano; Clusium; Thermo-mineral sites.

questo numero di Engramma è a invito: la revisione dei saggi è stata affidata al comitato editoriale e all'international advisory board della rivista

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: J. Tabolli, D. Barbagli, C. Felici, The Etruscan and Roman territory of Trequanda (Siena, Italy). Rediscovering the ancient “thermal” complex of Pieve di Santo Stefano a Cennano at Castelmuzio, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 214, luglio 2024, 85-104 | PDF