Hotel Montecarlo nearby the archaeological area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme

The archival sources

Maddalena Bassani and Maria Elena De Venanzi

Abstract

Introduction

1 | The most important archaeological areas at Montegrotto Terme (graphic reprocessed after Ghedini et aliae 2015, 12).

In the spa town of Montegrotto Terme, various pre-Roman, Roman and post-antique contexts are known, that testify to the development of the settlement from the 7th century BC to late Antiquity and until the Middle Ages, without interruption up to the present day around the hyperthermal saline-bromine-iodine thermal springs (86°C: [Fig. 1] (Lazzaro 1981; Grandis 1997; Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2011; Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2012; Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2013; Ghedini et alii 2015; Bassani et aliae 2021).

The exploitation of the thermo-mineral resource, present not only in Montegrotto Terme but throughout the entire Euganean Hills water basin (Brogiolo 2017), has in fact been the main factor of wealth and economic development, and has enabled, over time, both the use of thermal mud, now certified and known on an international level (Gris et alii 2020), along with secondary products such as stone formations and minerals, and everyday use (applications of thermal water heat, its motive power, and its properties for agricultural and domestic uses: Bassani 2014; Bassani 2017). In addition to this main resource, recent studies have also documented the dynamics that occurred in the area in relation to, for example, livestock breeding and agriculture (Varanini, Demo 2012), as well as the extraction and processing of Euganean trachyte (Zara 2018).

Considering the conspicuous amount of archaeological, literary, cartographic and documentary sources on how man has settled in and exploited mineral waters over the centuries, scarce attention has so far been paid to an apparently minor but, arguably, no less interesting category of documents, namely the archival sources pertaining to the construction of the spa hotels in the Euganean towns, i.e. those documents from relatively recent times that are preserved in municipal archives and those of the Archaeological Superintendence. In fact, the buildings for the accommodation of the numerous thermal users who came to Montegrotto Terme in particular, not only from Italy but often also from abroad from the post-war period to the present, have undergone a great phase of development from the post-war period onwards, and are today in many cases in a state of abandonment and decay, so much so that the Municipality has been led to step in with demolitions and redevelopment projects in synergy with the Archaeological Superintendence of Padua (Pettenò et aliae 2012).

Archive documentation relating to the second half of the 20th century can therefore be significant not only to reconstruct, albeit in fragments, the evolution of the urban and socio-cultural dynamics of those years, but also to recover evidence about the events that affected the archaeological sites, which are fortunately visible and can be visited today, but which at the time were not fully perceived as attractors of economically useful cultural tourism (see the effective observations proposed by Daniele Manacorda in a recent work: Manacorda 2014).

The following pages describe and analyse a number of documents recently recovered as part of the research activities of the Centro Studi classicA of the Iuav University of Venice (De Venanzi 2022): they shed light on the south-eastern sector of the area of Via Scavi, i.e. on the construction, close to the two major Roman thermal baths, of Montecarlo Hotel, which is today in a state of total abandonment and serious deterioration.

M.B.

Hotel Montecarlo in Montegrotto Terme and the Roman thermal baths in archive documentation

Hotel Montecarlo is located in the immediate vicinity of the archaeological area of the Euganean spa town between Viale Stazione and Via Scavi. Not only does the hotel border the archaeological site, but the embankment supporting the hotel's imposing structure cuts through and partially conceals two of the ancient Roman pools in the excavated thermal complex, namely basins A and B [Fig. 2]. In order to understand the dynamics involved in the construction of this hotel structure, research was conducted into the documentation in the municipal archives of Montegrotto Terme and in the archives of the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio of Padua (Padua Superintendence for Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape). The aim was to understand and compare the construction and archaeological events that occurred between 1950 and 1970, with particular regard to the construction of this hotel structure and the re-discovery of the Roman thermal baths, which had already been brought to light in the 18th century (Mandruzzato 1789-1804), but were subsequently re-interred until new excavation work was carried out in the second half of the 20th century [Fig. 3].

2 | View of Montecarlo Hotel from the south-east side of the archaeological area between Viale Stazione and Via Scavi; notice part of the eastern wall of the Roman cistern A (photo by Authors, 2022).

3 | Plan of the archaeological area of viale Stazione/via Scavi with identification of the rooms and representation of the direction of water flow in the pipes (graphic reprocessed after Bonomi, Malacrino 2011).

The documentation in the archives of the Municipality of Montegrotto concerning the construction of Montecarlo Hotel does not contain any information on the archaeological area bordering the building, which includes, as is well known, three bathing pools with adjoining rooms for additional therapies (Bonomi, Malacrino 2012, 155-172), a small theatre-odeum (Bonomi, Malacrino 2011, 29-55), a polylobate building subject to recent analyses that suggest its similarity to a nymphaeum (Bassani 2022, 101-123), and some service rooms. The general plans for the construction of Montecarlo Hotel, which were attached to the first building permit dating back to May 1961, show a white area without any particular distinguishing marks. The first graphic table for the architectural project of the hotel, where the archaeological remains are indicated, dates back to February 2000: it is a D.I.A. (denuncia di inizio attività = pre-declaration of works) for internal works to adapt to fire prevention rules [Fig. 4] (see Documentary Sources, 01). An extract of the P.R.G. is in fact present in the table, where the archaeological area is marked with a special screen; moreover, the general plan indicates an ‘AREA ARCHEOLOGICA’, although the ancient structures are not drawn.

4 | Tavole Denuncia Inizio Attività per opere interne di adeguamento alla prevenzione incendi PROGETTO-planimetrie, archive of the Municipality of Montegrotto, febbraio 2000 (Courtesy of Municipality of Montegrotto Terme).

The only actual reference to the Roman remains in the municipal archives is a set of three letters dating back to 1977 that pertain to problems of sewage infiltration in the archaeological area caused by a leak in the hotel piping (see Documentary Sources, 02-03-04). In fact, Montecarlo Hotel’s sewage pipes had to intercept (or reuse?) part of the ancient Roman hydraulic canals, thus causing serious sewage stagnation inside the Roman tanks. Moreover, the problem must not have been solved afterwards, as hints to such infiltrations were even recently given, during the renovations carried out between 2010 and 2012, when the hotel was by then in a state of complete abandonment (Pettenò et aliae 2012, 248-249).

The letters are dated from 30th June to 18th July 1977 and, apart from this infiltration incident, there is no other reference to Roman remains in the files dating between 1961 and 2000: this, despite the fact that the first archaeological discovery in Viale Stazione dates back to 1953, i.e. almost a decade before the construction of the historic spa hotel began and a good 150 years after the famous 18th-century excavation season documented by Salvatore Mandruzzato (Mandruzzato 1789-1804). In fact, the first building authorisation for the Montecarlo dates back to 1961 and the construction proceeded until the first floors were declared fit for habitation in 1968. However, as mentioned above, the first information on the excavation activities in Viale Stazione dates back to 1953, but there is no mention of the large thermal baths: in fact, the discoveries concern both a minor structure that was immediately demolished (De Venanzi 2022, 78-86), and the first elements related to the Roman theatre.

It seems therefore interesting to understand whether the previous archaeological documentation published by Salvatore Mandruzzato was taken into account when starting new excavations and the construction of Montecarlo Hotel between 1953 and 1961, or why the rapid construction of the hotel was not halted to conduct timely archaeological investigations. On the other hand, Scarabello construction firm that built Montecarlo hotel had been involved in the excavation of the ancient theatre as early as 1956 (see Documentary Sources, 05) and the owner of the firm, Carlo Scarabello, was the owner of the Montecarlo: it appears evident that those involved in the new construction were aware of all the discoveries and new findings in the archaeological area.

5 | Land registry map with the areas affected by the ancient structures, Montegrotto Terme: Excavation essay at the Montagnola, report accompanied by explanatory schematic drawings of the excavation essay and the cadastral plan of the area of interest, Archive of the Padua Superintendence, January 1956 (by courtesy of ASAP Padova).

6 | Schematic representation of the Via Scavi/Viale Stazione area (processing based on orthophotos from Google Maps).

.jpg)

7 | View of the large pool A at the archaeological site of Via Scavi/Viale Stazione cut by the concrete embankment of Montecarlo Hotel (photo by Authors, 2022).

8 | View from Viale Stazione of the access road to Montecarlo Hotel bordering the archaeological area (photo by Authors, 2022).

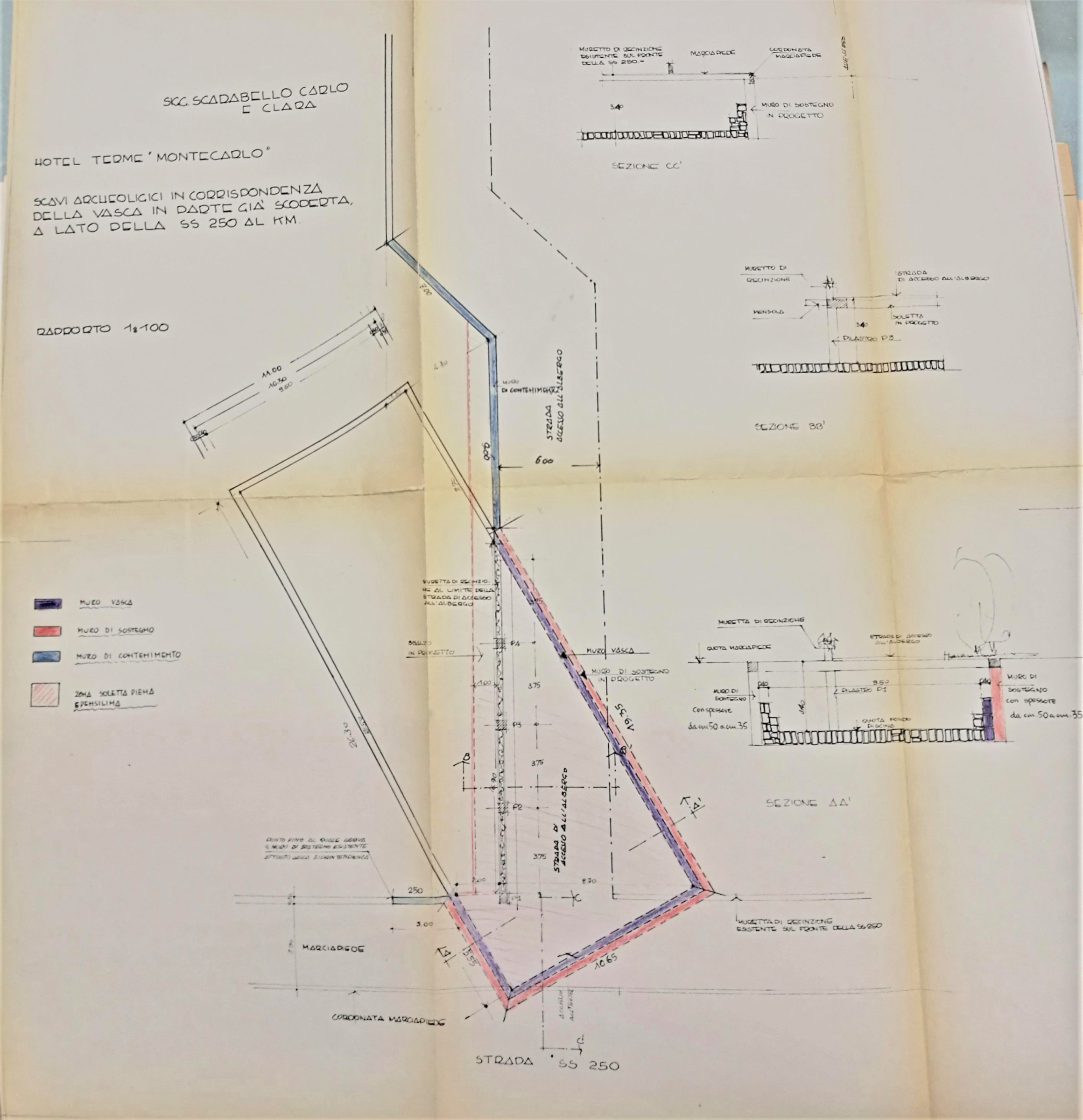

9 | Project to unearth pool A in Via Scavi, letter by Geom. Scarabello - Edilizia civile e industriale, opere stradali e movimenti di terra alla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova, archive of the Padua Superintendence, May 1968 (su autorizzazione ASAP Padova).

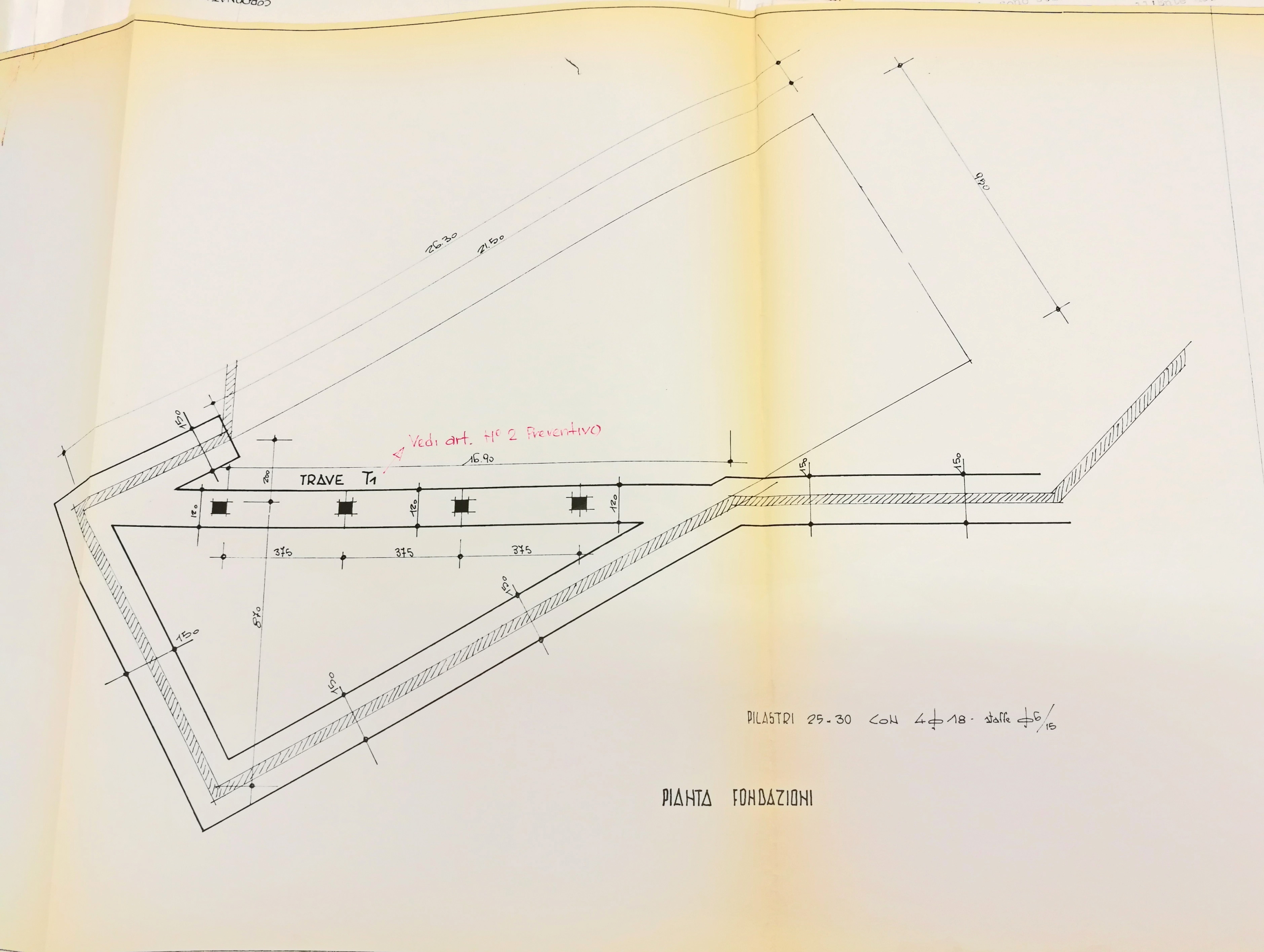

10 | Foundation plan of the project to bring the Via Scavi basin to light, letter by Geom. Scarabello - Edilizia civile e industriale, opere stradali e movimenti di terra alla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova, archives of the Padua Superintendence, May 1968 (by courtesy of ASAP Padova).

Research in the archives has provided interesting elements in this respect. The first document regarding the problematic relationship between the ruins and the new accommodation facility is to be found in the Archives of the Superintendence of Padua and corresponds to a land registry map with the location of the Roman thermal baths (see Documentary Sources, 05): it is dated 4th January 1956 and represents the maps of sheet VII of the Montegrotto Terme Municipality on a scale of 1:2000 [Fig. 5]. The hand-drawn plan shows the area created by the intersection of viale Stazione with the first section of via Scavi (extended in the following years), while the areas restricted by the Superintendence are coloured in red and correspond to the listed maps with all the relative owners in the top right-hand corner; the list is given here:

126 B and L was Crivellario Mario di Ferdinando of the late Pestoni Luigi (Saccolongo Padova)

46 A and D was Crivellaro Mario di Ferdinando of the late Pestoni Luigi

n. 46 D (242) ownership Berton Resina of Crivellaro Mario (Saccolongo Padova)

nn. 126 A-B-L 48 A-B-C owners. Pestoni Luigi of the late Gaetano (Montegrotto Padova).

In the drawing, the restricted area appears as extensive as the entire complex brought to light today. Even more remarkable is the shape of the mappings 48 A-B, which precisely follow the shape of the Roman baths, some of which were still buried: even the three mappings 48 A-B-C follow the shape of the three large baths and the rooms connected to them. This correspondence cannot certainly be accidental and proves that in January 1956 the plan of the spa complex was known at least well enough to mark a secure boundary between the land to restrict and the land to be parcelled out for new tourist constructions. It can therefore be stated with certainty that both the Superintendence and Impresa Scarabello (the firm in charge of the construction of the Montecarlo) in 1956 knew the boundaries of the restricted land parcels and the position of the ancient structures still buried there. It should also be pointed out how clearly visible in the plan is the land parcel in the name of Scarabello Geom. Carlo (where the Montecarlo was to be built in 1968) adjacent to the land parcels 48 A-B-C, which extend eastwards, creating a highly irregular boundary of the restricted area. The foundations of the hotel were to be built not far from the pools, and the outlines of the latter, marked on this map, lay under the side access road to the hotel and Viale Stazione [Fig. 6].

The land remained under restriction in the following years too, during which the Superintendence sought funds to begin a systematic excavation and build a small museum. However, it was not until 25th August 1965 (nine years later) that excavations were allowed to begin, bringing to light the remains of the ancient theatre, witnessed by many newspaper articles of the time where, however, there is no mention of the thermal baths. The latter are mentioned for the first time in the documents kept in the Superintendence in a letter from the Superintendent Giulia Fogolari to the Padua Chamber of Commerce, dated 23rd October 1965 (see Documentary Sources, 06):

It is reported that work carried out in 1965 brought to light a small theatre building dating back to the first centuries of the empire, which is of exceptional interest due to its architectural features and different construction phases (it is a type hitherto unknown in northern Italy) in a good state of preservation so as not to rule out a full tourist exploitation. In addition, emerged buildings and a complex of pools occupying an area of approximately 2000 square metres are identified. It is said that these discoveries require careful exploration in order to establish respective relations and valorisation criteria within the framework of the creation of a vast and important archaeological park area, the first in the Padua thermal area.

The “complex of pools” mentioned in the letter, although not further described, was clearly located together with the theatre in the area of 2000 square metres; but in the same months, on the adjacent land, the foundations of the Montecarlo were being built, as testified by a letter dated 18th June 1965 sent by the Director of the Civic Museum of Padua to the Superintendence: in the text, the Director, Alessandro Prosdocimi, denounced the presence of ancient remains under demolition inside the Montecarlo building site (see Documentary Sources, 07):

I am informed that in Montegrotto, next to the Albergo Sollievo, where foundations are being built for a new hotel, a Roman brick wall with a ladder has been found. The wall, which is of considerable proportions, is currently submerged in water and is being demolished.

Even today, going from the centre of Montegrotto towards the railway station, Sollievo hotel is located on the left just after the disused Montecarlo building: the ‘new hotel’ to which the director refers is thus precisely the Montecarlo spa hotel, whose foundations were under construction in June 1965 (as confirmed by the building documents in the municipal archives). Unfortunately, there is not enough information about the ‘Roman brick wall with a staircase’ to connect it to the nearby spa complex, but it is highly probable that these ancient structures, perhaps a small pool with steps, were part of the complex of the ancient health resort. Excavations, limited to the theatre, in the area in viale Stazione stopped in the autumn of 1965 and resumed on 4th April of the following year, with 12 workers working thanks to funding obtained by a committee especially set up in October 1965 (see Documentary Sources, 08): 1 million lire was allocated by the Hoteliers and another million lire by the public thermal care authority. With the resumption of archaeological excavations, the problem of the remains lying below the access road to the hotel was immediately brought to light. In May, the Superintendence asked Mr Scarabello for permission

To carry out soundings under the service road of his property, subject to the opening by the Superintendence of an alternative route.

As the foundations of the hotel had been finished by 1966, the request to carry out excavation tests indicates that it was hoped to unearth the baths still intact and not demolished during the construction of the Monte Carlo, which lay some 7 mt from the boundary with the archaeological area. The same idea seems to be supported in an article published by the ‘Difesa del Popolo’ on 17th July 1966, where the findings following the excavations of the same year are described and where the thermal baths are finally mentioned (see Documentary Sources, 09):

Attached to the theatre are the baths, consisting of three large pools, two round and one quadrangular, partly still covered by a wall soon to be demolished [as we know, the pools are one circular and two rectangular: the text evidently contains an error, ed].

The article by Mariangela Ballo also highlights the problem of the hotel adjacent to the archaeological area:

But in order to extend the excavations, considerably serious difficulties must be overcome; for example, the one posed by a large hotel that stands right in front of the archaeological area. Will it be possible to overcome them? It would certainly be a wonderful thing if the whole ancient Roman Montegrotto were to come back to light.

According to the data gathered so far, therefore, in 1966 the Superintendence had also begun to unearth the pools and, given the evident continuation of the remains underneath the hotel building site whose foundations had already been completed, excavation tests were intended to be carried out in the area of the Scarabello property in order to understand how to bring to light the still-buried part of some of the ancient structures. The work was interrupted at the beginning of July 1966 due to a lack of funds and then resumed on 22nd August thanks to the arrival of a 3 million Lire grant from Rome (see Documentary Sources, 10-11). Further information on the state of the excavations can be found in a letter from the Superintendence in 1967 in relation to the fencing of the excavations in Montegrotto (see Documentary Sources, 12), in which it is specified that:

The area has been fenced off along the west and south sides with retaining walls at ground level so as to prevent water infiltration and ground subsidence from the street side. Along the east side bordering the Scarabello property, a short section of wall of a different nature had previously been built by this Superintendence to allow the passage of the construction firm trucks.

It is evident from the text that at least part of the eastern boundary wall of the archaeological area was built by the Superintendence itself in agreement with the Scarabello company in order to allow lorries and other vehicles to reach the site, while at the same time attempting to protect the ancient structures: the aforementioned wall thus appears to be the one delimiting the archaeological area from the private portion where the secondary access road to the hotel is still present [Figs. 7-8]. After the break in the winter season, excavations resumed in September 1967 thanks to funds under the management of the Superintendence. A communication dated 10th August listed the planned work (see Documentary Sources, 13):

– construction of the access stairs to the archaeological area;

– landscaping of the garden in the part without remains;

– the most urgent restoration work;

– continuation of the excavation towards Montecarlo hotel.

Regarding the continuation of the excavations, the discovery in the Superintendence archives of the existence of a complete project to bring to light the rectangular apsidal basin A, digging under the access road to Montecarlo Hotel and Viale Stazione, appears to be of some importance; the graphic documentation of this project has been recovered [Figs. 9-10]. The complete estimate with the costs for this work was sent by land surveyor Carlo Scarabello to the Superintendence on 27th May 1968 (on this date the hotel had already obtained compliance status for the first floors, so it was in the final stages of construction: see Documentary Sources, 14):

Following your kind invitation, we would like to submit to you our best cost estimate for the work to bring to light the entire basin next to Montecarlo Hotel, in the archaeological area of Montegrotto Terme-Viale Stazione.

The project therefore envisaged a collaboration between the Scarabello firm, which had already worked in the archaeological area, and the Superintendence in order to uncover part of the southern pool without blocking the access road to the spa hotel: the creation of an accessible covered area was planned by inserting pillars directly inside the Roman pool to support the road above. The planned works included several actions:

1. the removal of earth to bring the entire pool to light and the transport of material to the landfill site (a job that could be done either by hand or with mechanical diggers);

2. the supply and laying of four 20-cm-wide pillars, placed along the entire length of the underground pool;

3. the supply of concrete and iron for the supporting and retaining wall of the covering;

4. roofing slabs for the basin and the associated shelter;

5. the cement mix to build a protective wall delimiting the road;

6. the plaster and mortar to be laid on the exposed surfaces;

7. the relocation of the route of the existing pipes above the basin (which included the aqueduct, methane pipeline and sewer);

8. the felling of tall trees in the area of operation, in order to allow the remains to be viewed without hindrance.

The cost of the works, excluding the necessary permits and any final arrangements of the fence between the archaeological area and the hotel, was estimated at 6.581.847 lire. Attached to the proposal were a number of graphic hand-drawings by Engineer Mario Geremia and dated 27th March 1968: they depicted the operation as a whole, with an abundance of details by means of plans, sections and reinforced concrete calculations. The project drawings show in blue the existing retaining wall of the access road to the hotel, which was to be diverted (the project retaining wall is shown in red: [Fig. 9]), and in grey the wall built by the Superintendence inside Roman pool A: in the new project the retaining wall would flank the perimeter of the old pool, as marked in purple on the plan. In place of the demolished wall, four pillars (P1-P2-P3-P4) would be inserted, 3.75 mt apart, which seem to have been placed in the middle of the Roman basin: they were to support the roofing slabs and the fence wall between the hotel property and the archaeological area. The project drawings also include a plan of the foundations of the four new pillars connected to a series of beams (in the plan collectively indicated as T1, each 1.2 mt wide for a total length of 16.9 mt): the detailed description of this wooden foundation in the estimate in point 2 is of interest:

Supply and installation of 4 N.P. of 20 cm for pillar base foundations placed side by side along the entire length of the pool, at a distance between centres of 30 cm, the cost of fitting into the slab of the pool included in the price, the transversal welding of 9 iron beams, 20 cm in length, at each pillar and on the heads for fixing among them, and the filling of the gap between the iron beams with cement concrete with 300 kgs of fine-grained gravel, and brushing on the visible side.

N.B.: No provision has been made for a continuous plinth foundation for the above-mentioned pillars cast prior to the excavation, in the slab of the pool, because in the very probable case that the ground is not of good consistency, it would be necessary to drive in cement piles, with obvious greater expense.

The estimate explains that the pillars were fixed to a foundation beam embedded in the ‘slab of the pool’ and that it was composed of 9 metal profile joists shaped as a double T, 20 cm long, placed at a distance between centres of 30 cm and joined by cement concrete to fill the spaces between the joists. Looking at the project sections, it is clearly visible how the insertion of the project pillars allowed for the creation of a portico of the same dimensions in plan as the ancient pool, resulting in a roof at an internal height of 3 mt. Towards the archaeological area, a small shelf was also planned to protect access to the covered area (project section BB’: [Fig. 9]).

The project therefore envisaged the preservation of the pavement of Viale Stazione and the access road to the hotel through the creation of a portico underneath, which would completely free the ancient basin, bringing it back to light; this covering was perhaps also intended to allow people to enter the basin and carry out any conservation work. Despite the fact that the project appeared detailed and ready to be implemented, there is no longer any reference in subsequent documentation to the excavation of the thermal pool buried under Montecarlo Hotel’s side street, and even today it remains partly trapped in the boundary wall of the now abandoned hotel, and partly under Viale Stazione. There are various hypotheses that may have halted the project: either more urgent restoration work was carried out, or there were no funds left to further extend the excavations on the eastern side, or, finally, there were problems with the feasibility of the project that have not been mentioned in the documentation, such as, for example, the failure to obtain a permit to carry out these works.

From 1969 onwards, relations between land surveyor Scarabello and the Superintendence seem to have been limited to ordinary maintenance work, since, based on archive documentation, the company no longer seems to have collaborated directly in archaeological excavations.

M.E.D.V.

Some remarks on the archival documentation

The documents presented here pertaining to the archaeological area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme, which refer to the period between the 1950s and 1970s, allow us to reconstruct, albeit in fragmentary form, some significant aspects of the history of archaeology in this Euganean town, shedding new light on aspects of conservation and planning, connected to the general socio-economic situation of the time.

On the one hand, the documentation preserved in the archives of the Superintendence of Padua and the Municipality of Montegrotto Terme shows the complexity of the dynamics that existed between those who were in charge of protecting the archaeological heritage of the Veneto town and those who wished to benefit economically from the development of tourism linked to the thermal mineral resource, a development that was also promoted thanks to State benefits, which funded sessions of thermal cures paid by the public health service.

The rush to build hotel facilities to accommodate large numbers of guests led, here as in many Italian cities, to the prevailing interest in an economic well-being that, after the collapse caused by the Second World War, promised a rosy future of profits, at the expense, evidently, of the preservation of everything that lay underground, which was to be excavated and transformed in favour of progress. It is therefore not surprising that the institutions in charge of protection had a hard time finding agreements with private individuals, as also emerged with regard to the events surrounding the excavation of nymphaeum D (the so-called polylobate building) in Via Scavi in the summer of 1970 and the acquisition of the entire area by the State (Bassani 2022). On the other hand, however, the documents analysed above also highlight the attempt by the Superintendence to try to contain the serious effects caused by the aggressive building boom of those years, which disrespected both the archaeological heritage and the landscape in its entirety: it is well known how the Euganean area, and in particular the town of Montegrotto Terme, completely changed its appearance after the Second World War, losing its rural village character in favour of a pseudo-urban identity, characterised by gigantic hotel structures in utter disharmony with the natural environment.

Indeed, the project to unearth the underground portion of the A basin in Via Scavi below the side street of Montecarlo Hotel, although never carried out, highlights the effort to restore to the public what had been compromised, and the awareness of the importance of combining a newfound economic well-being with a solid shared historical memory of what the area of the Patavini Fontes (Plin. nat. 31, 61) had been in ancient times. We do not know why the project was not put into practice: on the other hand, we can rejoice at this failure, because the sensitivity of today’s archaeologists, restorers and architects would hardly allow the construction of such a wall over an ancient artefact (such as the one built by the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage itself to delimit the archaeological area from Montecarlo Hotel property), or the creation of a pillar roof resting directly inside an ancient room, compromising its perfectly preserved horizontal plane (as the pool’s plane was at the time). It was perhaps a good thing that nothing came of this project, and it is not by chance that the archives of the Italian Superintendences collect many other examples of design hypotheses that were never completed: suffice it to think of the project for the creation of an underground café underneath the arch of the Roman bridge of S. Lorenzo in Padua, which was never executed (Vigoni 2018, in particular 141-146).

In conclusion, the archive papers that we have been able to examine represent a memento for future urban requalification activities, which we hope will be capable not only of preserving the ancient buildings in the best possible way and, if possible, bringing new portions of them to light, but also of enhancing them in a broader and more multifaceted vision: research and planning perspectives are needed, aimed at placing the artefacts of the past in dialogue with contemporary and possibly future times.

M.B.

We would like to thank the staff of the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Peasaggio of Padova and the Municipality of Montegrotto Terme for their willingness to publish the archival materials stored in their institution archives.

Bibliography

Documentary sources

- 01

Tavole Denuncia Inizio Attività per opere interne di adeguamento alla prevenzione incendi PROGETTO-planimetrie, Archivio del Comune di Montegrotto, febbraio 2000. - 02

Lettera dalla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova alla Direzione dell'Albergo Montecarlo, Montegrotto Terme (PD) – Zona archeologica di via Stazione, Archivio del Comune di Montegrotto, 30 giugno 1977. - 03

Lettera dal Commissario Prefettizio del Comune di Montegrotto Terme alla Direzione dell'Hotel Montecarlo, Infiltrazioni di acque nere nella zona archeologica di Viale Stazione, Archivio del Comune di Montegrotto, 8 luglio 1977. - 04

Lettera dalla Direzione dell'Hotel Montecarlo al Commissario Prefettizio del Comune di Montegrotto Terme e alla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova (oggetto non presente), Archivio del Comune di Montegrotto, 18 luglio 1977. - 05

Montegrotto Terme – Saggi di scavo presso la “Montagnola”, relazione accompagnata da disegni schematici esplicativi dei saggi di scavo e della planimetria catastale dell'area di interesse, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 4 gennaio 1956. - 06

Lettera dalla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova alla Camera di Commercio Industria e Agricoltura di Padova, Scavi archeologici in Montegrotto Terme, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 23 ottobre 1965. - 07

Lettera dal Direttore del Museo Civico di Padova alla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova (oggetto mancante), Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 18 giugno 1965. - 08

Lettera dal Presidente A. Simonato alla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova, all'Azienda di Cura, all'Associazione Albergatori e al Sindaco di Montegrotto Terme, Ripresa scavi in Montegrotto Terme - Padova, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 23 marzo 1966. - 09

A Montegrotto Terme tra i moderni alberghi. Qui sotto c'è un teatro! (ma nessuno voleva crederci), «La Difesa del Popolo», Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 17 luglio 1966. - 10

Si stava portando alla luce un antico teatro. Sospesi per mancanza di soldi i lavori di scavo a Montegrotto. I progetti sono ambiziosi ma la realtà è triste – un parco archeologico, Gazzettino, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 10 agosto 1966. - 11

Il finanziamento ministeriale per gli scavi di Montegrotto. Sono giunti i tre milioni richiesti ed i lavori hanno potuto riprendere, Resto del Carlino, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 6 settembre 1966. - 12

Lettera dalla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova all’Avv. Luciano Salmazo, Recinzione scavi di Montegrotto, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 3 gennaio 1967. - 13

Lettera dalla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova al Presidente dell'Associazione Albergatori Luigi Pestoni, Montegrotto Terme – Scavi archeologici, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 10 agosto 1967. - 14

Lettera dal Geom. Scarabello - Edilizia civile e industriale, opere stradali e movimenti di terra (proprietario anche dell'Hotel Montecarlo) alla Soprintendenza alle Antichità di Padova (oggetto non presente), alla lettera sono allegati il preventivo di spesa per un lavoro e le relative tavole grafiche disegnate a mano dall'Ing. Mario Geremia e datate 27.03.1968, Archivio Soprintendenza di Padova, 27 maggio 1968.

References

- Bassani 2014

A. Bassani, Note idrotermali: caratterizzazione, prodotti, usi diversi, in M. Annibaletto, M. Bassani, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Cura, preghiera e benessere. Le stazioni curative termominerali nell'Italia romana, Padova 2014, 29-43. - Bassani 2016

M. Bassani, Soltanto 'salus per aquam'? Utilizzi non terapeutici delle acque termominerali nell'Italia romana, in I mille volti del passato. Studi in onore di Francesca Ghedini, a cura di J. Bonetto, M.S. Busana, A.R. Ghiotto, M. Salvadori, Roma 2016, 879-891. - Bassani 2022

M. Bassani, L’edificio polilobato in Via Scavi a Montegrotto Terme. Ipotesi per una sua interpretazione, “Rivista di Archeologia” XLVI (2022), 101-123. - Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2011

M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae patavinae. Il termalismo antico nel comprensorio euganeo e in Italia, Atti del I Convegno Nazionale (Padova 2010), Padova 2011. - Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2012

M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae patavinae. Montegrotto Terme e il termalismo e in Italia. Aggiornamenti e nuove prospettive di valorizzazione, Atti del II Convegno Nazionale (Padova 2011), Padova 2012. - Bassani, Bressan Ghedini 2013

M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae salutiferae. Il termalismo fra antico e contemporaneo, Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Montegrotto Terme 2013), Padova 2011. - Bassani et aliae 2021

M. Bassani, C. Destro, F. Ghedini, T. Privitera, P. Zanovello, Montegrotto Terme, Museo del termalismo antico e del territorio. Guida, Padova 2021. - Bonomi, Malacrino 2011

S. Bonomi, C.G. Malacrino, L’edificio per spettacoli di Fons Aponi. Considerazioni a margine dei rilievi effettuati nell’area archeologica di viale Stazione / via degli Scavi, in Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2011, 29-55. - Bonomi, Malacrino 2012

S. Bonomi, C.G. Malacrino, Il complesso termale di viale Stazione / via degli Scavi a Montegrotto Terme, in Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2012, 155-172. - Brogiolo 2017

G.P. Brogiolo (a cura di), Este, l’Adige e i Colli Euganei. Storie di paesaggi, Mantova 2017. - De Venanzi 2022

M.E. De Venanzi, L’area archeologica di Via Scavi a Montegrotto Terme: una proposta di riqualificazione, Tesi di Laurea magistrale in Architettura, Università Iuav di Venezia, Venezia 2022. - Ghedini et aliae 2015

F. Ghedini, P. Zanovello, M. Bassani, E. Brener, C. Destro, T. Privitera, M. Bressan, La villa di Via Neroniana a Montegrotto Terme (Padova) fra conoscenza e valorizzazione, “Amoenitas” IV (2015), 11-40. - Grandis 1997

C. Grandis, Montegrotto: una storia per immagini: mappe topografiche e fotografie del territorio, Montegrotto Terme 1997. - Gris et alii 2020

B. Gris, L. Treu, R.M. Zampieri, F. Caldara, C. Romualdi, S. Campanaro, N. La Rocca, Microbiota of the Therapeutic Euganean Thermal Muds with a Focus on the Main Cyanobacteria Species, “Microorganisms” 8.10 (2020), 1590. - Lazzaro 1981

L. Lazzaro, Fons Aponi. Abano e Montegrotto nell’Antichità, Abano Terme 1981. - Manacorda 2014

D. Manacorda, L’Italia agli Italiani. Istruzioni e ostruzioni per il patrimonio culturale, Bari 2014. - Mandruzzato 1789-1804

S. Mandruzzato, Dei bagni di Abano, voll. I-III, Padova 1789-1804. - Pettenò et aliae 2012

E. Pettenò, M. Rigoni, P. Toson, L. Zega, Riapertura dell’area archeologica di viale stazione / via degli Scavi. Interventi di risanamento e di restauro, in Bassani, Bressan, Ghedini 2012, 247-255. - Varanini, Demo 2012

G.M. Varanini, E. Demo, Allevamento, transumanza, lanificio: tracce dell’alto e dal pieno Medioevo veneto, in M.S. Busana, P. Basso, A.R. Tricomi (a cura di), La lana nella Cisalpina romana. Economia e società. Studi in onore di Stefania Pesavento Mattioli, Atti del Convegno (Padova-Verona, 18-20 maggio 2011), Padova 2012, 269-287. - Vigoni 2018

A. Vigoni, Documenti archeologici inediti della Patavium liviana: il caso del porto fluviale, in F. Veronese (a cura di), Livio, Padova e l’universo veneto nel bimillenario della morte dello storico, Atti della giornata di studio (Padova, 19 ottobre 2017), Roma 2018, 133-148. - Zara 2018

A. Zara, La trachite euganea. Archeologia e storia di una risorsa lapidea del Veneto antico, voll. 1-2, Roma 2018.

The article presents previously unpublished data concerning the events surrounding the urban and building works between 1950 and 1970 near the archaeological area of Montegrotto Terme, with special attention to the construction of Montecarlo Hotel above parts of the Roman baths of the ancient curative complex. Thanks to the analysis of archive documentation, an architectural project is also presented, aimed at making visible the partially altered underground part of one of the two ancient pools, which has never been carried out.

keywords | Thermalism, Archaeological excavations, Archival sources, Architectural design.

questo numero di Engramma è a invito: la revisione dei saggi è stata affidata al comitato editoriale e all'international advisory board della rivista

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: M. Bassani, M.E. De Venanzi, Hotel Montecarlo nearby the archaeological area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme. The archival sources, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 214, luglio 2024, 149-170 | PDF