I. Introduction

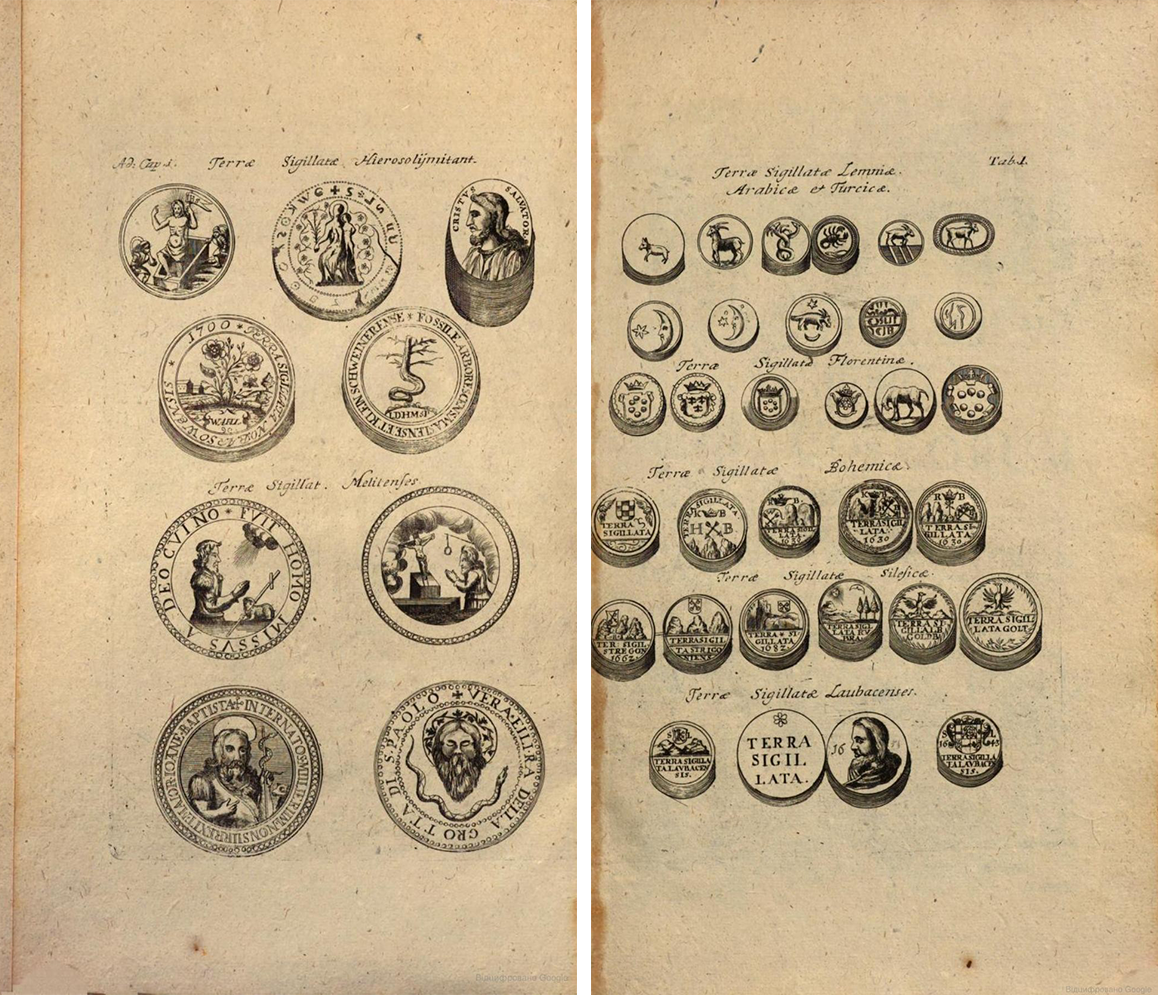

1 | Collection catalogue of Terrae Sigillate. Source: Michael Bernhard Valentini, Museum Museorum, oder vollständige Schau-Bühne aller Materialien und Specereyen, Volume II (1714) tab. 1.

Among the many curious and even controversial aspects of daily life in classical antiquity, perhaps one of the least known – yet surprising – is the story of geophagy. Geophagy can be defined as a deliberate consumption of earth and clay, although its actual underlying reasons are still under scrutiny and not completely understood yet. Several types of clay were known at these times, and believed to have therapeutic properties; thus, sometimes they would be carefully selected, processed and used to treat different health issues. The earth of Lemnos, for example, according to Dioscorides (De Materia Medica, V, 113), was mixed with goat blood, and formed into tablets; then consumed to treat various health conditions. For the purpose of easier recognition, the healing tablets of Lemnos, also referred to as the medicinal Terra Sigillata, carried a stamped image on them [Fig. 1]. Although it can be recognised as an unusual and somewhat controversial practice, one could also easily associate it to what we may find in our own cupboards today, where supplement tablets are stored on shelves, usually separated by colour, and often consumed with water or milk.

A great part of information on various types of Terrae Sigillatae, among them medicinal ones of Lemnos, was passed on to us through medieval sources. These specific fonts were especially of the rise during 16th and 17th centuries many of which included illustrated catalogues – with one of the examples depicted in the figure 1. The stamps collected were deeply valued not only for their reputed powers but also for their, to a certain extent, heraldic designs, making the possession of samples from the most famous sources a recognized badge of distinction.

Today, modern medicine classifies geophagy as a form of Pica — a mental, behavioural, or neurodevelopmental disorder (World Health Organisation 2018: Pica is recognised as persistent consumption of non-food substances — things that are not nutritionally appropriate and not culturally accepted as food). However, the practice of geophagy has been observed throughout human history and, moreover, is not unique to our species but is documented across a wide range of animal species as well (Abrahams 2012; Panichev et al. 2013; Pebsworth et al. 2019).

Within animal species, earth consumption seems to be a mechanism of ion exchange and selective adsorption, helping supplementation of deficient elements and removal of excess ones. Studying its roots in human species is a challenging task, as prehistoric behaviour needs to be inferred without the support of written records. While some scholars have proposed that geophagy already occurred in prehistoric and preclassical sites (Young et al. 2011; Brady and Rissolo 2006; Root-Bernstein and Root-Bernstein 2000; Abrahams 2012) such hypotheses require cautious interpretation. It was not until the emergence of structured societies and advancement of medical knowledge that geophagy took on a more systematic and widespread role. The earliest known to us documented instances of intentional soil consumption date back to Ancient Greece and Rome, where recipes and prescriptions involving specific types of earth began to appear in written texts (Celsus, De Medicina medica (med.); Dioscorides, De materia medica (mat. med.); Pliny the Older, Naturalis Historia (nat.); and others). These records offer a glimpse into a more formalized understanding of geophagy and its perceived health benefits.

II. The elemental earth

From the scientific perspective, earth can be described as a natural heterogeneous mixture composed of minerals, organic matter, water and air. Within this matrix, clay refers to a naturally occurring fine-grained material of mineral origin. The specific mineral composition varies with parent material, climate, and geological history, influencing soil fertility, texture, and function (Velde 1995). Formation of clays in hydrothermal systems depends on various factors including the composition of the parent material, pH conditions, or temperature. Kaolinite groups, for example, are often found in moderately acidic systems (pH 4.5-6) and temperatures (150-200°C) while many magnesium rich clay minerals such as biotite or talc will form under alkaline conditions in combination to temperatures between 200-350°C (Fulignati 2020).

The mineralogical character of clays formed within hydrothermal systems is governed by a complex interplay of impacts, including the mineralogical composition of parent material, the temperature–pressure regime, or the prevailing pH of the circulating fluids. For instance, kaolinite-group minerals characteristically form under moderately acidic conditions (approximately pH 4.5-6), where elevated hydrogen ion activity promotes extensive hydrolysis of feldspars and other aluminosilicates. These phases are typical of low- to intermediate-temperature hydrothermal regimes, generally <200°C. Conversely, magnesium-rich phyllosilicates exhibit markedly different stability requirements. Minerals such as talc, saponite, or even Mg-enriched biotite compositions tend to form under alkaline to mildly alkaline conditions, typically associated with intermediate to high hydrothermal temperatures, commonly within the range of ~200-350°C. And, as we will see later on, it is specifically clays that emerge as the preferred substance in geophagy practices (Abrahams 2012). Their selection is not random, as we will see, as different earths (thus different clay matters) are often referenced as remedy ingredients, and they are clearly separated by their colour or geographic origin.

In modern times, while the direct ingestion of raw soil or clay has become less common, the underlying impulse remains. Today, humans frequently consume isolated and purified mineral supplements, such as calcium, magnesium, or iron, processed into tablets and taken with water, milk, or honey. This shift from natural to refined sources could represent a form of continuation of the ancient practice, now recontextualized within the framework of contemporary health and nutrition.

III. Insights from written sources

2 | Ancient medical experts, Vienna Dioscurides. Cited after (Tomaselli 2021).

The use of clay-based materials in classical antiquity has been documented in several classical texts, and encompasses a broad range of practices, including oral ingestion, external application for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes, and mixed uses in medicinal, ritual, and technological contexts. Only a subset of the earth and clay names recorded might be directly correlated to the geographical locations of their probable provenance. Although no original writings are known to have survived to the present day, many were recopied over the centuries, and several late antique palimpsests and medieval copies and are still known to us today (Licht 2000; Reeve 2007; Granados 1978). Among the most significant sources are the writings of Pliny the Elder, Pedanius Dioscorides, Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Theophrastus, and others, whose works serve as rare windows into ancient practices and customs, offering us a glimpse into the ancient ways. Figure 2 for example represents an image taken from Vienna Dioscorides – a preserved manuscript from 512 AD. The image itself is depicting seven famous ancient physicians, identified in (Rothenhöfer 2018) as Cheiron and Machaon – mythological figures known for their expertise in medicine and healing; Pamphilus of Alexandria, physicians Xenocrates of Aphrodisias, Heracleides of Tarentum and Mantias; and finally, pharmacologist Sextius Niger. Same are known as first authors on Greek medicinal and pharmaceutical writings.

Perhaps a good way to start the story could be with the character of Philoctetes, built from early pre-Homeric times to Sophocles’ version (Mackie 2009). His physical agony was derived from a poisonous snake wound, and his emotional one was emerging from the loneliness of being abandoned by the Greek army at the island of Lemnos. In Sophocles’ play (649f., 696-698f.) we can see that, to ease his agony, although without success, he used special herbs found on the island itself. Philostratus Flavius mentions the healing of Philoctetes’ wound by the priests of Hephaistos who used Lemnian bole (bolos-lamp) (Photos-Jones, Hall 2014) e.g. the earth of Lemnos Island “onto which Hephaistos is said to have fallen” (Heroikos, XXVIII, 1-14). We cannot, thus, help but wonder about the link between Philoctetes’ poisoned snake bite on the island of Lemnos and one of the most intriguing ancient healing recipes, that of goat blood mixed with Lemnian earth (mat. med., V 113; nat., XXXV, 14). The medicine was well studied and described by (Thompson 1913), where he argues that the medicinal recipe of the Terra Sigillata seals of Lemnian earth have survived through medieval times and were documented in some medieval manuscripts [Fig. 1]. He presents further the findings of his mineralogical composition analysis of Lemnian earth samples: high silica percentage with iron, calcium and aluminium oxides (Thompson 1913).

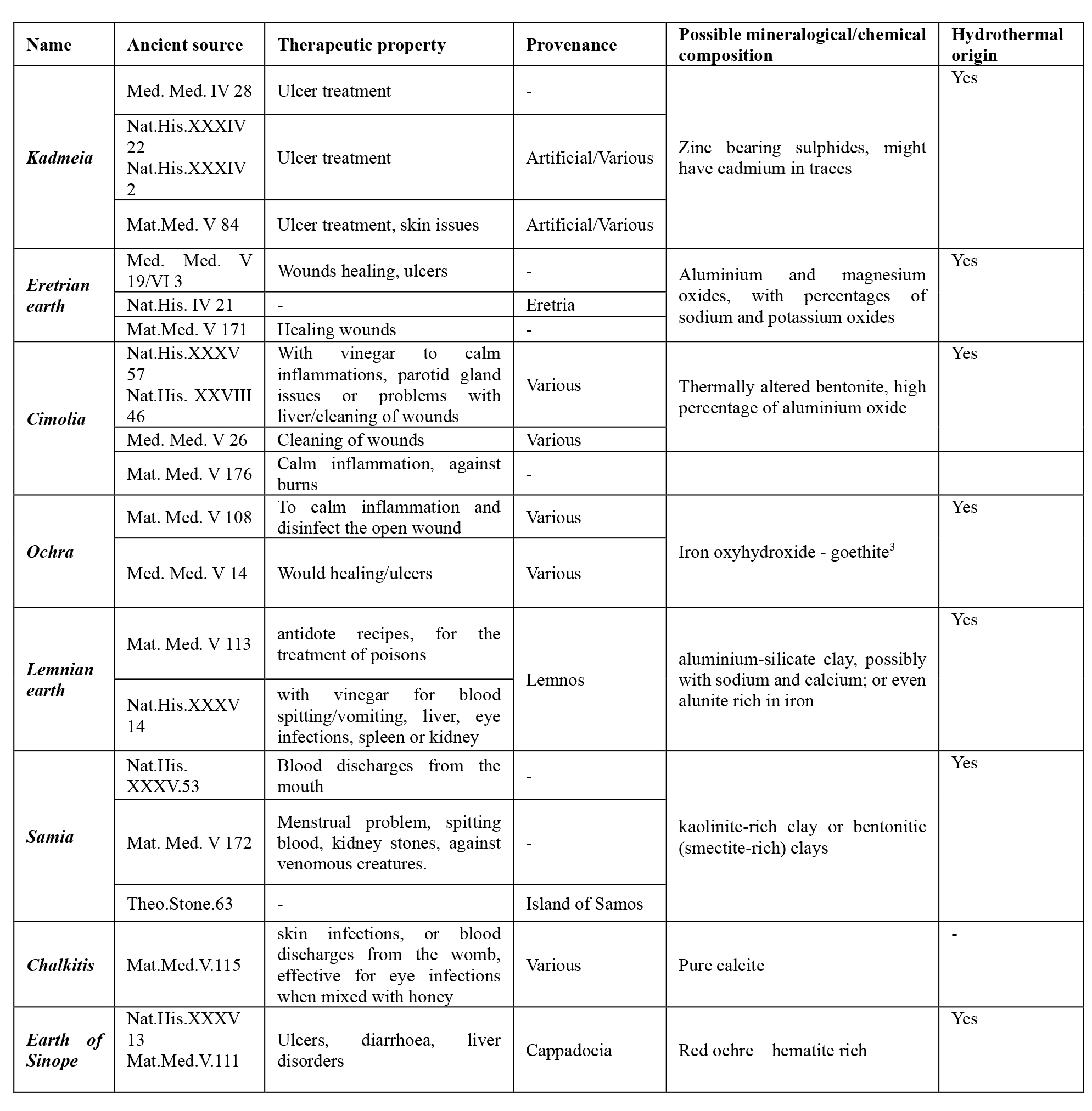

Lemnian earth, however, is not unique. Many other types of earths, clays and inorganic mixtures have been studied and described in classical texts, of which some will be mentioned here (Table in Fig. 6). What is interesting perhaps is that majority of recipes is quoted as remedies for wounds, whether in the form of ulcers (med. IV 28; nat., XXXIV, 22; nat. XXXIV, 2; mat. med., 5-84), mouth bleeding (nat. XXXV, 14; nat., XXXV, 53) or wound disinfection (mat. med., 5-171; mat. med., 5-108).

On Samian earth, for example, Dioscorides writes (mat. med., V 154, 2):

ἵστησι δὲ αἵματος ἀναγωγὴν, καὶ ῥοϊκαῖς δίδοται γυναιξὶ σὺν βαλαυστίῳ · καὶ ὄρχεων καὶ μαστῶν φλεγμoνὰς καταχριομένη σὺν ὕδατι καὶ ῥοδίνῳ παύει·

στέλλει καὶ ἱδρῶτας· καὶ θηριοδήκτοις καὶ θανασίμοις ἀρήγει, σὺν ὕδατι πινομένη.

It stops blood from being spat up, and is given to women with a flux, accompanied by pomegranate blossoms. When smeared with water and rose essence, it stops inflammation of the ovaries and breasts; it also reduces sweating; when taken in a drink of water, it helps against wild animal bites and poisons.

We can understand from the text that it was a verry precious medicinal earth used for various conditions. Combined with the flowers of wild pomegranate, for example, for regulating women’s menstrual flows when drank. Applied as a paste with water, it soothed inflammation caused by stones (urinary or kidney) and eased breast inflammation. When taken instead with a drink of water, it was believed to reduce excessive sweating and to serve as an antidote for venomous bites or the ingestion of “deadly medicines”.

Cadmium Earth was another classical remedy, said to be particularly effective in the treatment of ulcers, wounds, and skin ailments. Its name could refer to Cadmus, the legendary Phoenician founder of Thebes in Boeotia (Beekes and Beek 2010). Both Dioscorides and Pliny describe it in detail. Dioscorides distinguishes several types of kadmeia, as botryitis, zonitis, and ostracitis, each differing in colour and properties (Mat. Med. V 114). He further explains that kadmeia could be obtained artificially by heating brass in a furnace, as the resulting soot adhered to the walls of the chamber.

3 | Red figure lekythos depicting Philoctetes on the island of Lemnos with his wounded leg. Location: Metropolitan Museum of Art, USA.

Pliny also mentions Cadmium Earth on two occasions. First, he identifies it as a natural form of copper ore (nat., XXXIV, 2), and afterward he describes the artificial variety produced through the same process outlined by Dioscorides – the burning of copper ores and collection of the metallic deposits (nat., XXXIV, 22). He writes Metalla aeris multis modis instruunt medicinam, utpote cum ulcera omnia ibi ocissime sanentur, maxime tamen prosunt cadmea, indicating that copper metals (ores or perhaps earths) are all potent in medicine, but cadmium is the most useful.

On Eretrian Earth Celsus writes (med. VI 3):

Super utrumque (ulcera) oportet inponere elaterium aut lini semen contritum et aqua coactum aut ficum in aqua decoctam aut emplastrum tetrapharmacum ex aceto subactum; terra quoque Eretria ex aceto liquata recte inlinitur.

In both (ulcers) it is good to apply elaterium, or pounded linseed worked up in water, or a fig boiled in water, or the plaster tetrapharmacum moistened with vinegar; also Eretrian earth dissolved in vinegar is suitable for smearing on.

He talks in fact about the special type of ulcer growing usually on the head, on which he claims Eretrian earth diluted in vinegar, as one of the effective medicines, should be applied. Beside as ulcer balm, Eretreian Earth was believed to be a powerful and universal wound-healing remedy as well (med., V 19/VI 3; nat. IV, 21; mat. med. V, 171). Pliny unveils its origin as that of the ancient city of Eretria in the island of Euobea (nat., IV, 21). On the use of Earth of Sinope, Pliny writes (nat., XXXV, 13):

… (Sinopsis) sive sicca compositione sive liquida facilis, contra ulcera in umore sita, velut oris, sedi.

It admits of being easily used, whether in the form of a dry or of a liquid composition, for the cure of ulcers situate in the humid parts of the body, the mouth and the rectum, for instance.

Claiming that it can be used in the form of a dry or of a liquid composition, for the cure of ulcers, such as ones growing in the mouth and the rectum. He further adds:

Alvum sistit infusa, feminarum profluvia pota denarii pondere. eadem adusta siccat scabritias oculorum, e vino maxim.

Used as an injection, it arrests looseness of the bowels, and, taken in doses of one denarius, it acts as a check upon female discharges. Applied in a burnt state, with wine in particular, it has a desiccative effect upon granulations of the eyelids.

Suggesting that it can be used for diarrhoea, or discharges – depending on the method of use and amount. He adds that if applied in a burnt state, with wine in particular, it has a desiccative effect upon granulations of the eyelids (nat., XXXV, 13). We have to note that the word that Pliny uses is infusa – eng. infused. The needle injection was not available in classical times and thus, this particular medicine was most probably drunk or applied directly to the ill spot. Dioscorides, on the other hand, suggests it mixed with egg to stops the bowels (diarrhoea), or for liver disorders (mat. med., V 111). He uses the term infused as well – […] tum etiam clystere infusa – indicating similar application (Lat. Infusio ~ onis: the pouring in or on (the medications): Lexicon Universale Latinitatis (1968) Oxford, at the Clarendon Press).

Another powerful remedy exploited in classical times is Cimolian Earth. Two forms of Kimolia are described by Pliny, without a detailed clarification on their composition or provenance. Kimolia – the earth (nat., XXXV, 57) – is good, he states, taken with vinegar to calm inflammations, parotid gland issues or problems with liver. It could be applied externally as well, he continues, when mixed with aphronitrum, oil of cypros and vinegar, to reduce the swelling or used as sun lotion (there are some indications that this name could refer to hydro-carbonate of soda: Healy 2000). Kimolia – the chalk – according to his writings can serve to disinfect the wounds (nat., XXVIII, 46), the property that was indicated by Aulus Cornelius Celsus as well (med., V 26). Kimolia seems to provenance from various sources – Sardinia, Umbria, Lycia (nat., XXXV, 57).

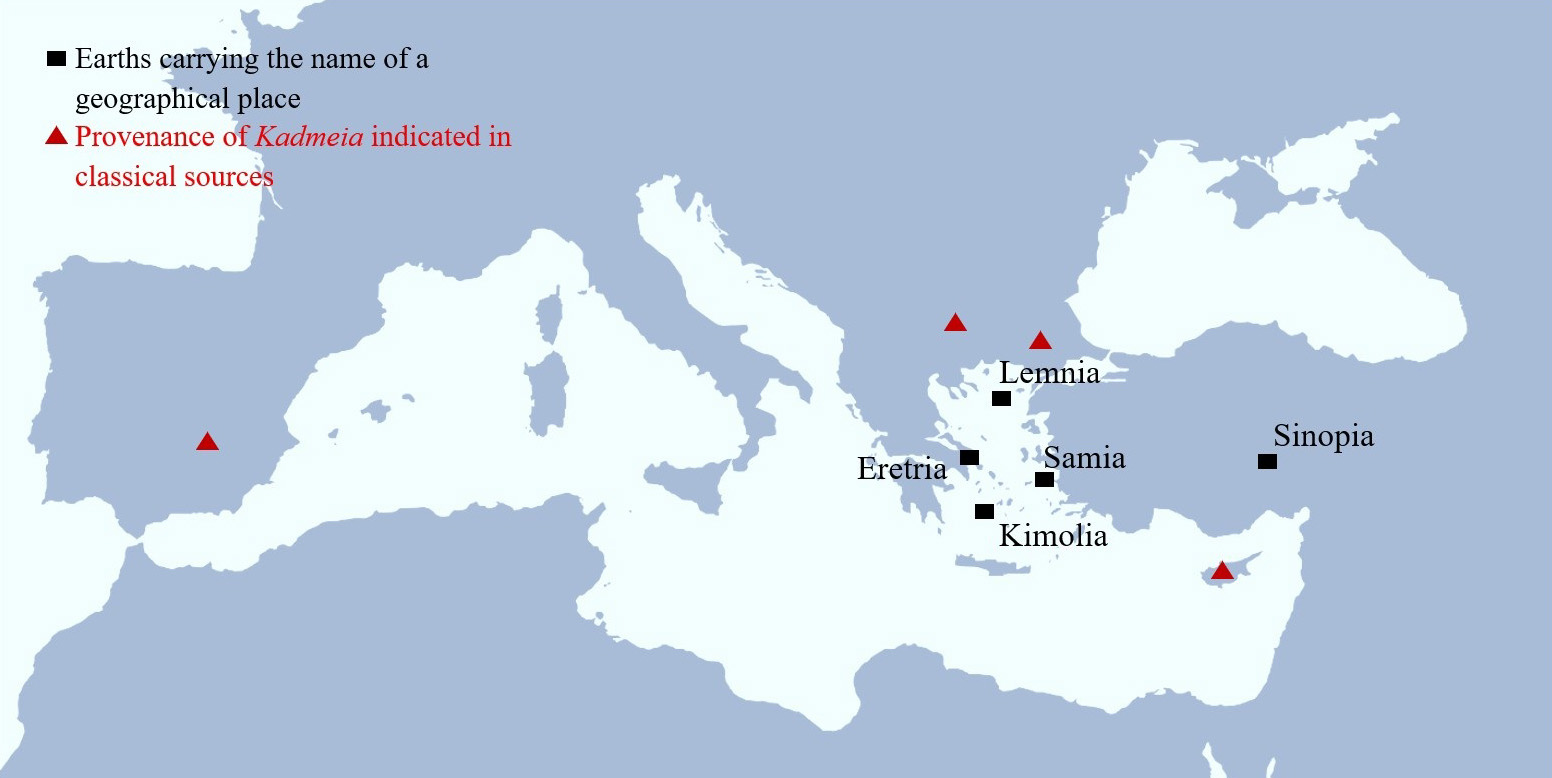

4 | Late Roman medicinal gem made of hematite, building mineral of red ochra, with inscription When you are thirsty, Tantalos, drink blood. The British museum, artefact code: 1928,0520.1.

Clay ochra is frequently mentioned in ancient sources as well (Diosc., mat. med., V, 108; mat. med., V, 111; Cels., med., V, 14). It has been valued for its antiseptic qualities, and both Dioscorides and Celsus describe its use for reducing inflammation and disinfecting open wounds (Diosc., mat. med., V, 108; mat. med., V, 111; Cels., med., V, 14). Red earths, commonly referred to as ochres, comprise clay-rich materials exhibiting warm yellow to brown chromatic tones whose coloration derives principally from the presence and amount a of iron-bearing accessory phases, most notably the ferric oxide hematite and the ferric oxyhydroxide goethite. Hematite, which derives its name from Greek word αίμα – meaning blood, was often used for the production of medicinal gems. One example was shown in the figure 4 – the amulet depicting Tantalos, and bearing a disappearing inscription “Tantalus drink blood…”, whose meaning and use have long been a product of discussion. The words inscribed have been interpreted in various ways, as those associated with cessation of bleeding and connections to the waters of Hades, retreating whenever Tantalus attempts to drink; to ones perceived as having the potential to alleviate Tantalus’s curse, and allowing the bleeding in the cases when it is beneficial, as for example menstrual bleeding is (Faraone 2009). Finally, Dioscorides mentions as well the medical use of calcium carbonate (chalkitis) (mat. med., V, 99, 2). He writes:

ποιεῖ δὲ καὶ πρὸς ἐρυσιπέλατα, ἕρπητας, αἱμορραγίας τὰς ἐξ ὑστέρας καὶ μυκτήρων σὺν πράσου χυλῷ· ξηρὰ δὲ πρός τε ἐπουλίδας καὶ νομὰς καὶ παρίσθμια· κεκαυμένη δὲ πρὸς τὰ ὀφθαλμικὰ μᾶλλον χρησιμεύει λεία σὺν μέλιτι· τετυλωμένα μὲν βλέφαρα καὶ τραχέα ἀποτήκει καὶ σμήχει.

With leek juice, it is effective for erysipelas, herpes, and discharges of blood from the womb and nostrils. Its powder is effective in treating growths on the gums, spreading ulcers, and inflammation of the tonsils. If burnt, it is far more effective for eye diseases when finely ground and mixed with honey; it reduces and wipes hardened and rough eyelids.

arguing that in combination with leek juice it can help cure skin infections, herpes or blood discharges (from womb for example), or mixed with honey for eye infections. What is interesting is that this particular material might be present in other writings as well, but in another form – as creta Cimolia or Cimolian chalk (Plin., nat., XXIX, 35; Cels. med., V, XXVII). Celsus talks about mixture of Cimolian chalk with frankincense in water to treat skin irritations, while Pliny mentions it for treating scalp ulcers in combination with sheep’s gall. Dioscorides refers to psōrikon (mat. med., V, 99,3), a preparation composed of calcium carbonate and Cimolian earth, which is said to be used for the same purposes as chalkitis. He provides a detailed recipe:

Σκευάζεται δὲ ἐξ αὐτῆς τὸ καλούμενον ψωρικὸν, διπλασίονος χαλκίτεως πρὸς ἁπλὴν καδμείαν μιγνυμένου, καὶ σὺν ὄξει λεαινομένου· δεῖ δὲ ἐν· κεραμέῳ ἀγγείῳ κατορύσσειν ἐν κοπρίᾳ ἐν τοῖς ὑπὸ κύνα καύμασιν ἡμέρας μ΄.

So-called psoricum is made from it, with two parts calcitis and one part cadmia mixed together and finely ground and then mixed with vinegar. The mixture must then be tightly sealed in a ceramic jar buried in dung and left for forty days during the hottest period of the year.

In this process, he explains, two parts of calcium carbonate are mixed with one part of kadmeia and ground together with vinegar until smooth. The mixture is then placed in a ceramic vessel and buried in dung, where it is left to mature for forty days under the heat of the summer sun.

IV. Provenance of medicinal earths and their relationship to hydrothermal sources

Little is known about the precise mineralogical composition and formation process of medicinal clays described in classical sources. Although many are associated with specific topographic names, such as Lemnian, Samian, or Cimolian earth — the name could all the same refer to clays extracted from multiple localities, likely resulting in variations in chemical and physical properties. Such nomenclatural conventions can, however, be misleading, as illustrated by the case of the so-called earth of Sinope. Although Sinopia is geologically derived from deposits in Cappadocia (Becker 2022), it acquired its name from the Black Sea port of Sinope, the principal node through which it entered Mediterranean trade networks. Pliny nonetheless refers to it as Sinopica (nat., XXXV, 13), and whether he was familiar with its true provenance cannot be established with certainty. Dioscorides, by contrast, demonstrates a clearer awareness of its geographic origin: in De Materia Medica (V, 111), he refers to the substance as miltos (rubrica) Sinopike, while explicitly acknowledging its Cappadocian source.

The island of Lemnos was in Classical times well-known for its Lemnian fire (τὸ Λήμνιον πῦρ) and as the place of workshop traditions of Ephesus (Marchiandi 2016). Although geological investigations have excluded the presence of volcanic activity that could have given rise to the myths associated with the Lemnian fire, it remains plausible that the region was characterised by natural methane emissions – highly flammable gas seeps (Etiope 2015), comparable to those documented at Yanar Dağ in Azerbaijan or the eternal flames of the Chimaera at Olympos. During his travels on the island, Galen provides a detailed description of the Lemnia extraction locations. He writes: “This earth comes from Lemnos, the island otherwise called Stalimene, and is found close to a town called Hephestias, on the top of a red-stained hill, barren of plants and with the appearance of having been burnt”(cited after: Thompson 1913) This account aligns closely with the environmental characteristics of natural gas seeps, which, owing to elevated soil temperatures, shifts in soil pH, and oxygen displacement, typically exhibit an absence of vegetation and soils altered to a burnt or baked appearance.

In 1913, Thompson publishes a first analysis on the mineralogical composition of Lemnia, based on, as he stated, the 16th century sample he was fortunate to obtain (Thompson 1913). His results show well anticipated mineralogical composition, commonly found in clays – high amounts of silicates, accompanied by ferric, aluminium and calcium oxides as well, along with some minor quantities of magnesium and alkalis (Thompson 1913). Some contemporary analysis on Lemnian Earth define it as an aluminium-silicate clay (Photos-Jones, Hall 2014), occasionally enriched with sodium and calcium; or containing alunite, an insoluble potassium aluminium sulphate mineral. Notably, aluminosilicate clays associated with alunite are well known to form under medium-temperature (≤ 200°C) acid-sulphate hydrothermal conditions, typically involving the alteration of igneous substrates (Şener et al. 2017; Photos-Jones, Hall 2014; Fulignati 2020).

5 | Provenance of medicinal earths.

In addition, several Aegean islands with hydrothermally altered volcanic rocks were recognized in antiquity as sources of medicinal clays, including Samos and Kimolos (Photos-Jones et al. 2015) [Fig. 5]. Major hydrothermal systems of this area is found along the volcanic chain stretching out from Milos to Kos (Dando et al. 2000). The ferrous and non-ferrous building elements in the Aegean hydrothermal sediments have been identified as those of iron, magnesium, zinc, manganese, copper and aluminium (Megalovasilis 2014).

Samian earth might be related to kaolinite-rich clay or bentonitic clays, often found in association with local borate minerals (Photos-Jones et al. 2015). Both kaolinite and bentonite are known as well to form in areas of hydrothermal alteration of lavas and tuffs. A comparable composition is observed in Cimolian Earth from Kimolos, characterized as a thermally altered aluminium-rich bentonite (Al₂O₃·4SiO₂·H₂O) with notably high aluminium oxide content (Christidis 1998).

6 |Some of the earths mentioned in ancient text and considered in this article.

Classical authors also reference various geographical provenances of Cadmium Earth, as those of Cyprus, Macedonia, Thrace or Spain (Diosc., mat. med., V, 84; Plin., nat., XXXIV, 22). Some more recent studies argue about its mineralogical provenance, as that of calamine (De Vos 2010), a zinc-bearing mineral well-known in classical times; or that of cobalt minerals as suggested by Endlich in 1888 (see historical sources listed). Although the term cadmeia has etymological affinity with cadmium (Cd), cadmium pigments were only isolated and identified in the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, it may be important to notice that cadmium traces are naturally occurring in some non-ferrous and ferrous metal ores such as galena (PbS), chalcopyrite (CuFeS) or sphalerite (ZnS) (Bao et al. 2022, Sattar et al. 2025), of which the last is zinc sulphide. Calamine and sphalerite are both zinc-bearing minerals, but they represent different forms of zinc in the natural oxidation cycle of ore deposits. Sphalerite (ZnS) presents what may be defined as a primary zinc sulphide phase, from which smithsonite, hemimorphite and hydrozincite can be formed through weathering (Boni, Mondillo 2015). In addition, studies have indicated that all three of these secondary phases might be considered a building minerals of what was known as calamine in classical times (Aversa et al. 2002, Merkel 2021). In classical and early modern metallurgy for example, calamine was considered any zinc-rich carbonate/silicate used to make brass by cementation with copper, as ancient metallurgists did not distinguish between its different building phases (Merkel 2021).

Existing research on Eretrian Earth is comparatively scarce: however, there are some indications that it may be related to aluminium-rich clays, with high percentage of iron oxide hematite (Fe₂O₃), and some presence of magnesium and sodium oxides (Charalambidou et al. 2016, 2018). By contrast, ochre is well-known, composed predominantly of hematite and goethite (α-FeOOH) and abundantly found in nature. In aqueous systems for example, it can be formed through hydrothermal precipitation as the fluids through their flow interact with the surrounding rocks (Cornell, Schwertmann 2003). Goethite, a common iron-bearing mineral primarily composed of iron (III) oxide-hydroxide, forms in aqueous environments by precipitation of soluble FeIII and hematite from FeIII species at temperatures higher that 100 °C, in aqueous media and at neutral pH (≅7) (Cornell, Schwertmann 2003).

Among the notable studies linking ochre to the earliest therapeutic or ritualised practices is the well-documented burial from the Late Mesolithic site of Bad Dürrenberg, interpreted as that of a healer or shaman. The burial of an elderly woman accompanied by a child was entirely enveloped in a fine-grained ochre layer consisting of almost pure hematite (Porr, Alt 2006) reinforcing the symbolic and functional link between healing practices and iron-rich earths.

It is important to note however, that ochres in classical times referred to a yellow clay, while red ochres were known are rubrica (Becker 2022). Earth of Sinope – rubrica Sinopica (mat. med., V, 111), for example, was one of the most valuable red ochre earths. Geochemical investigations of the hydrothermal terrains of Cappadocia, the true provenance of sinopia, reveal iron-rich lithologies and alteration products consistent with hematite-dominated assemblages, which might confirm the mineralogical origin of rubrica Sinopica as that of red ochre i.e. hematite rich clay.

The mineralogical patterns emerging from the analyses presented above indicate that many of the clay and oxide phases characteristic of the investigated medicinal earths exhibit diagnostic signatures of hydrothermal alteration. This observation might suggest that hydrothermal processes played a significant role not only in the genesis of the constituent clay and oxide minerals, and by extension origin of extraction, but also in shaping the broader cultural and therapeutic frameworks within which these materials were employed. In this sense, hydrothermal systems may be understood as holistic geological environments in which water, heat, and mineral-rich substrates interacted to produce naturally occurring assemblages gifted with distinctive physical and chemical properties. Such settings would have offered ancient communities a convergence of therapeutic waters and clays – resources that were readily integrated into medicinal, hygienic, and ritual practices.

V. Modern insights

All the earths mentioned in classical texts may have been modified by human intervention, through processing or treatment of natural clay and ore deposits. However, more scholarly attention has been given recently to the medicinal properties of clays, as a more sustainable way to treat a variety of medical issues.

Beside clays, other secondary products within hydrothermal sites found their application in classical antiquity (Cataldi 2005; Bassani 2024, 2021). Greeks extracted sulphur from thermal springs, a substance to them divine (θεῖος), and they used it in healing and purification rituals (mat. med., V, 124). Waters rich in sodium, potassium or iron found their therapeutic use within healing structures as well (Bassani 2014). In Hamat-Gader thermal baths refined clay lumps have been found (Dvorjetski 2007), indicating the potential clay use in curative hydrothermal rituals. Taking this into account, it is important to evaluate whether recent understandings of clay-based therapeutics can substantiate the inferred medicinal applications observed in classical contexts.

Lemnian Earth is well studied, and some results showed antibacterial and microbiome properties (Photos-Jones et al. 2015) and beneficials for gut health (Milling et al. 2024). Potential antibacterial activity is observed in Samian Earth as well, where findings suggest that this earth, when mixed with specific minerals, can exhibit exhibits antibacterial effects, supporting, for example, its historical use in treating eye infections (Photos-Jones et al. 2015). The obtained results may be related to some contemporary observations on therapeutic properties of aluminosilicates especially those of kaolinite which might exhibit anti-inflammatory, analgesic effects; and have demonstrated as gastrointestinal protector and antidiarrhoeic (Awad et al. 2017, Carretero 2002), those of bentonites which indicate some anti-inflammatory properties as well (Cervini-Silva et al. 2015), or perhaps even of zeolites possibly demonstrating some detoxifying, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects (Oggiano et al. 2023).

The medicinal properties of ochre are well studied as well, with some indications of antiseptic benefits in wound sterilization (Tributsch 2016). In addition, iron oxide nanoparticles found their application in modern medicine for various purposes, including their use as antiviral and antimicrobial agents (Attia et al. 2022).

Exposure to earths rich in cadmium, on the other side, emphasized the toxicity risks (Charkiewicz et al. 2023). However, as discussed earlier, the mineralogical origin of Cadmium earth may be traced to zinc bearing ores, with the possibility that cadmium as metal in ancient clays used in therapeutic rituals was only present in traces. Zinc has indeed shown some medical benefits, as those of wound healing (Xiao et al. 2025) or antimicrobial effects (Pino et al. 2023). These properties could be related to the applications of Kadmia for ulcer and wound treatment, reported, as we saw earlier, in the ancient sources (see Table in Fig. 6).

Contemporary scientific literature does not yet provide specific medicinal or pharmacological studies on Cimolian and Eretrian earths. However, the elevated concentrations of aluminium oxides documented in these clays may be relevant, given that aluminium-rich mineral phases have been associated with pronounced antimicrobial activity, including inhibitory effects against E. coli and S. epidermidis, as well as photothermal bactericidal responses (cited after Hassanpour et al. 2018). In addition, investigations conducted on natural clays containing varying proportions of aluminium, iron and magnesium oxide percentages, similar to what is observed in the samples of Lemnian Earth, have revealed a shared capacity to promote epithelial wound healing (Incledion et al. 2021). This effect appears to be mediated, at least in part, by the intrinsic antibacterial properties of these mineral assemblages.

Finally, in addition to antibacterial properties observed in calcium carbonate and calcium magnesium carbonate (Yamamoto et al. 2010), the general role of calcium ions on preserving skin barrier is recognised (Nopriyati et al. 2022), and it might have been a reason for such widely use of calcium carbonate in treating skin-related issues in classical activity.

VI. Conclusions

Several classical medicinal earths, described in ancient sources, may possess complex mineral compositions that closely reflect the therapeutic effects historically attributed to them. As modern science increasingly turns toward natural and sustainable solutions, and continues to investigate the properties of natural materials such as clays, there may be a growing potential to explore these earths in greater depth in future studies. By considering their mineral content through the lens of contemporary understandings of clay composition and genesis, meaningful connections emerge between ancient practices and modern scientific knowledge. Many of these earths appear to originate from hydrothermal environments, where natural conditions favor the formation of specific mineral assemblages.

Rather than interpreting the use of thermal waters and medicinal clays as sequential or causally hierarchical phenomena, hydrothermal sites may be more appropriately understood as integrated sacred environments, in which waters, gases, minerals, and earth materials collectively derived their therapeutic and symbolic value from the perceived potency of place. Within such landscapes, healing practices likely emerged from a holistic engagement with the environment, in which mineral-rich waters and locally available clays were experienced as interconnected expressions of the same natural agency. These observations might underscore a deliberate selection of materials associated with naturally occurring geothermal phenomena, rising intriguing questions about the role of hydrothermal sites and sanctuaries in ancient healing practices. Did the extraction and use of clays as a direct response to the presence of these sacred sites, or were thermal waters the primary driver, subsequently supplemented by the collection of locally occurring clays? In other words, which came first — the recognition of the healing properties of the mineral-rich waters, or the deliberate sourcing and use of clays from these hydrothermal environments? Understanding this dynamic might be essential for reconstructing the interplay between natural resources and ritualized healing in classical antiquity.

Bibliography

Historical references and modern translations

- Heroikos, XXVIII

Flavius Philostratus: Heroikos, Eng. transl. J.K. Berenson Maclean, E. Bradshaw Aitken, Atlanta 2001. - mat. med. V

Dioscorides, De materia medica, Eng. transl. T. Osbaldeston, Johannesburg 2000. - mat. med. V

Dioscorides, Pedanii Dioscuridis Anazarbei De materia medica libri quinque, 3 vol., ed. by M. Wellmann, Berlin 1907-1914. - med. IV, V

Aulus Cornelius Celsus, De medicina medica, Eng. transl. W.G. Spencer, London 1935. - nat. IV, XXXIV, XXXV

Gaius Plinius Secundus, Naturalis Historia, Eng. transl. J. Bostock, H.T. Riley, London 1855. - Theo. 63

Theophrastus. Περὶ Λίθων, Introduction, Greek text, Eng. transl., commentary by E.R. Caley, John F.C. Richards, Ohio 1956. - Valentini 1714

Michael Bernhard Valentini, Museum Museorum, oder vollständige Schau-Bühne aller Materialien und Specereyen, Volume II, Frankfurt 1714.

References

- Abrahams 2012

P.W. Abrahams, Geophagy and the Involuntary Ingestion of Soil, in O. Selinus et al. (eds.), Essentials of Medical Geology, Dordrecht 2013, 433-454. - Annibaletto et al. 2014

M. Annibaletto, M. Bassani, F. Ghedini, Cura, Preghiera e Benessere: Le Stazioni Curative Termominerali nell’Italia Romana, Padova 2014. - Attia et al. 2022

N.F. Attia, E.M. Abd El-Monaem, H.G. El-Aqapa, S.E.A. Elashery, A.S. Eltaweil, M. El Kady, S.A.M. Khalifa, H.B. Hawash, H.R. El-Seedi, Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Pharmaceutical Applications, “Applied Surface Science Advances” 11 (2022). - Aversa et al. 2002

G. Aversa, G. Balassone, M. Boni, C. Amalfitano, The Mineralogy of the “Calamine” Ores in SW Sardinia (Italy): Preliminary Results, “Periodico di mineralogia” 71/3 (2002), 201-218. - Awad et al. 2017

M.E. Awad, A. López-Galindo, M. Setti, M.M. El-Rahmany, C. Viseras Iborra, Kaolinite in Pharmaceutics and Biomedicine, “International Journal of Pharmaceutics” 533/1 (2017), 34-48. - Bao et al. 2022

Z. Bao, T. Al, J. Bain, H.K. Shrimpton, Y. Zou Finfrock, C.J. Ptacek, D.W. Blowes, Sphalerite Weathering and Controls on Zn and Cd Migration in Mine Waste Rock, “Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta” 318 (2022), 1-18. - Bassani 2014

A. Bassani, Note Idrotermali: Caratterizzazione, Prodotti, Usi Diversi, in M. Annibaletto, M. Bassani, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Cura, Preghiera e Benessere. Le Stazioni Curative Termominerali nell’Italia Romana, Padova 2014. - Bassani 2021

M. Bassani, Beyond Health. The Exploitation of Thermomineral Sources in Artisan Activities, in D. van Limbergen, D. Taelman (eds.), The Exploitation of Raw Materials in the Roman World, Cologne 2021. - Bassani 2023

M. Bassani, Thermal Cults. Pilgrimages to Mineral Springs between Antiquity and the Middle Ages, “La Rivista di Engramma” 204 (luglio/agosto 2023), 67-92. - Bassani 2024

M. Bassani, Healing with Mineral Waters. Places, Object and Written Sources in Roman Italy, “La Rivista di Engramma” 214 (luglio 2024), 105-126. - Becker 2022

H. Becker, Pigment Nomenclature in the Ancient Near East, Greece, and Rome, “Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences” 14/1 (2022). - Beekes, van Beek 2010

R.S.P. Beekes, L. van Beek, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Leiden-Boston 2010. - Boni, Mondillo 2015

M. Boni, N. Mondillo, The “Calamines” and the “Others”: The Great Family of Supergene Nonsulfide Zinc Ores, “Ore Geology Reviews” 67 (2015), 208-233. - Brady, Rissolo 2006

J.E. Brady, D. Rissolo, A Reappraisal of Ancient Maya Cave Mining, “Journal of Anthropological Research” 62 (2006). - Carretero 2002

M.I. Carretero, Clay Minerals and Their Beneficial Effects upon Human Health. A Review, “Applied Clay Science” 21 (2002), 155-163. - Cataldi 2005

R. Cataldi, La Geotermia nelle Antiche Civiltà Mediterranee, in R. Ciardi, M. Cataldi, Il Calore della Terra, Pisa 2005. - Cervini-Silva et al. 2015

J. Cervini-Silva, A. Nieto-Camacho, S. Kaufhold, K. Ufer, E. Ronquillo de Jesús, The Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Bentonites, “Applied Clay Science” 118 (2015), 56-60. - Charalambidou et al. 2016

X. Charalambidou, E. Kiriatzi, N.S. Müller, M. Georgakopoulou, S. Müller Celka, T. Krapf, Eretrian Ceramic Products through Time, “Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports” 7 (2016), 530-535. - Charalambidou et al. 2018

X. Charalambidou, E. Kiriatzi, N.S. Müller, S. Müller Celka, S. Verdan, S. Huber, K. Gex, G. Ackermann, M. Palaczyk, P. Maillard, Eretrian Ceramic Production through Time, “Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports” 21 (2018), 983-994. - Charkiewicz et al. 2023

A.E. Charkiewicz, W.J. Omeljaniuk, K. Nowak, M. Garley, J. Nikliński, Cadmium Toxicity and Health Effects—A Brief Summary, “Molecules” 28/18 (2023). - Christidis 1998

G.E. Christidis, Comparative Study of the Mobility of Elements during Alteration of Andesite and Rhyolite to Bentonite, “Clays and Clay Minerals” 46/4 (1998), 379-399. - Cornell, Schwertmann 2003

R.M. Cornell, U. Schwertmann, The Iron Oxides, Weinheim 2003. - Dando et al. 2000

P.R. Dando, S. Aliani, H. Arab, C.N. Bianchi, M. Brehmer, S. Cocito, S.W. Fowlers, J. Gundersen, L.E. Hooper, R. Kölbh, J. Kuevere, P. Linke, K.C. Makropoulosr, R. Meloni, J.-C. Miquel, C. Morri, S. Müller, C. Robinson, H. Schlesner, S. Sieverts, W. Ziebiss, Hydrothermal Studies in the Aegean Sea, “Physics and Chemistry of the Earth” 25/1 (2000), 1-8. - De Vos 2010

P. De Vos, European Materia Medica in Historical Texts, “Journal of Ethnopharmacology” 132/1 (2010), 28-47. - Dvorjetski 2007

E. Dvorjetski, Historical-Archaeological Analysis and Healing Cults of the Therapeutic Sites in the Eastern Mediterranean Basin, in E. Dvorjetski (eds.), Leisure, Pleasure and Healing, Leiden 2007, 125-223. - Endlich 1888

F.M. Endlich, On Some Interesting Derivations of Mineral Names, “The American Naturalist” 22 (1888). - Etiope 2015

G. Etiope, Natural Gas Seepage, Cham 2015. - Faraone 2009

C.A. Faraone, Does Tantalus Drink the Blood, or Not?: An Enigmatic Series of Inscribed Hematite Gemstones, in U. Deli, C. Walde (eds.), Antike Mythen: Medien, Transformationen und Konstruktionen, Berlin 2009, 248-273. - Fulignati 2020

P. Fulignati, Clay Minerals in Hydrothermal Systems, “Minerals” 10/10 (2020). - González Soutelo 2024

S. González Soutelo, Thermalism in the Roman Provinces, Oxford 2024. - Granados 1978

D.O. Granados, New Light on Celsus’ De Medicina, “Sudhoffs Archiv” 62/4 (1978), 359-377. - Hassanpour et al. 2018

P. Hassanpour, Y. Panahi, A. Ebrahimi-Kalan, A. Akbarzadeh, S. Davaran, A.N. Nasibova, R. Khalilov, T. Kavetskyy, Biomedical Applications of Aluminium Oxide Nanoparticles, “Micro & Nano Letters” 13/ 9 (2018), 1227-1231. - Healy 2000

J.F. Healy, Chemistry, in J.F. Healy (eds.), Pliny the Elder on Science and Technology, Oxford 2000, 115-141. - Incledion et al. 2021

A. Incledion, M. Boseley, R.L. Moses, R. Moseley, K.E. Hill, D.W. Thomas, R.A. Adams, T.P. Jones, K.A. BéruBé, A New Look at the Purported Health Benefits of Commercial and Natural Clays, “Biomolecules” 11/1 (2021), 58. - Licht 2000

W. Licht, Der „Wiener Dioscurides“, “Der Palmengarten” (2000), 25-31. - Mackie 2009

C.J. Mackie, The Earliest Philoctetes, “Scholia” 18 (2009). - Mantovanelli 2014

L. Mantovanelli, Acque Termali e Cure Mediche, in M. Annibaletto, M. Bassani, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Cura, Preghiera e Benessere, Padova 2014. - Marchiandi 2016

D. Marchiandi, Effesoto a Lemno: ''La piu cara tra tutte le terre'', in F. Longo, R. Di Cesare, S. Privitera (a cura di), ΔΡΟΜΟI studi sul mondo antico offerti a Emanuaele Greco, Atene-Paestum 2016, 743-766. - Megalovasilis 2014

P. Megalovasilis, Partition Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Precipitates, “Geochemistry International” 52/11 (2014), 992-1010. - Merkel 2021

S.W. Merkel, Calamine of the Bergamasque Alps as a Possible Source of Zinc for Roman Brass, “Periodico di mineralogia” 90 (2021), 247-259. - Milling et al. 2024

S. Milling, U.Z. Ijaz, D. Venieri, G.E. Christidis, N.J.W. Rattray, I. Gounaki, A. Andrusaite, A. Hareendran, C.W. Knapp, A.X. Jones, E. Photos-Jones, Beneficial modulation of the gut microbiome by leachates of Penicillium purpurogenum in the presence of clays: A model for the preparation and efficacy of historical Lemnian Earth, “PLOS ONE” 19/12 (2024). - Nopriyati et al. 2022

Nopriyati, A. Ligar Suherman, Y. Farida Yahya, M. Devi, The Role of Calcium in the Skin Barrier, “Bioscientia Medicina” 6/7 (2022), 1976-1988. - Oggiano et al. 2023

G. Oggiano, B. Pokimica, T. Popović, M. Takić, Beneficial Properties of Zeolite, “Italian Journal of Food Science” 35/1 (2023), 72-78. - Panichev et al. 2013

A.M. Panichev, K.S. Golokhvast, A.N. Gulkov, I. Yu. Chekryzhov, Geophagy in Animals and Geology of Kudurs, “Environmental Geochemistry and Health” 35/1 (2013), 133-152. - Pebsworth et al. 2019

P.A. Pebsworth, M.A. Huffman, J.E. Lambert, S.L. Young, Geophagy among Nonhuman Primates, “American Journal of Physical Anthropology” 168 (2019), 164-194. - Photos-Jones, Hall 2014

E. Photos-Jones, A.J. Hall, Lemnian Earth, Alum and Astringency, in D. Michaelides (eds.), Medicine and Healing in the Ancient Mediterranean World, Oxford 2014, 183–189. - Photos-Jones et al. 2015

E. Photos-Jones, C. Keane, A.X. Jones, M. Stamatakis, P. Robertson, A.J. Hall, A. Leanord, Testing Dioscorides’ Medicinal Clays, “Journal of Archaeological Science” 57 (2015), 257-267. - Pino et al. 2023

P. Pino, F. Bosco, C. Mollea, B. Onida, Antimicrobial Nano-Zinc Oxide Biocomposites, “Pharmaceutics” 15/3 (2023). - Porr, Alt 2006

M. Porr, K.W. Alt, The Burial of Bad Dürrenberg, “International Journal of Osteoarchaeology” 16/5 (2006), 395-406. - Reeve 2007

M.D. Reeve, The Editing of Pliny’s Natural History, “Revue d’histoire des textes” 2 (2007), 107-179. - Root-Bernstein, Root-Bernstein 2000

R.S. Root-Bernstein, M. Root-Bernstein, Honey, Mud, Maggots, and Other Medical Marvels, Boston-New York 1997. - Rothenhöfer 2018

P. Rothenhöfer, Mantias – An Eye Doctor of Emperor Tiberius, “Gephyra” 15 (2018), 191-195. - Sattar et al. 2025

S. Sattar, M. Yahya, S. Aslam, R. Hussain, S.M. Mukkarram Shah, Z. Rauf, A. Zamir, R. Ullah, A. Shahzad, Environmental Occurrence and Remediation of Cadmium, “Results in Engineering” 25 (2025). - Schwartz 2000

M.O. Schwartz, Cadmium in Zinc Deposits, “International Geology Review” 42/5 (2000), 445-469. - Şener et al. 2017

M.F. Şener, M. Şener, I.T. Uysal, Evolution of the Cappadocia Geothermal Province, “Hydrogeology Journal” 25/8 (2017), 2323-2345. - Thompson 1913

C.J.S. Thompson, Terra Sigillata, A famous medicament of ancient times, in C.J.S. Thompson, History of Medicine, London 1913, 433-444. - Tomaselli 2021

C. Tomaselli, The Vienna Dioscurides, “Smarthistory” (2021). - Tributsch 2016

H. Tributsch, Ochre Bathing of the Bearded Vulture, “Animals” 6/1 (2016). - Velde 1995

B. Velde, Origin and Mineralogy of Clays, Berlin 1995. - World Health Organisation 2018

World Health Organisation, International Classification of Diseases, 11th ed., Geneva 2018. - Xiao et al. 2025

D. Xiao, Y. Huang, Z. Fang, D. Liu, Q. Wang, Y. Xu, P. Li, J. Li, Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Skin Wound Healing, “Materials Today Bio” 34 (2025). - Yamamoto et al. 2010

O. Yamamoto, T. Ohira, K. Alvarez, M. Fukuda, Antibacterial Characteristics of CaCO₃–MgO Composites, “Materials Science and Engineering” 173 (2010), 208-212. - Young et al. 2011

S.L. Young, P.W. Sherman, J.B. Lucks, G.H. Pelto, L. Rowe, Why on Earth? Evaluating Hypotheses about Human Geophagy, “The Quarterly Review of Biology” 86/2 (2011), 97-120.

Abstract

Clays represent one of the earliest exploited natural materials in human history. Their significance extends far beyond the realms of craft production and artistic practice, and, as we will see later on, they have played a central role in therapeutic, medicinal, and ritual activities throughout classical antiquity. Many of the most valued clays originate in hydrothermal environments, where elevated temperatures, mineral–rich waters, and active water–rock interaction create ideal conditions for their creation. In addition, therapeutic and ritualistic uses of hydrothermal mineral–rich waters during the classical period have been well studied (Annibaletto, Bassani, and Ghedini 2014; González Soutelo 2024; Bassani 2023, 2024), and many of the minerals extracted from these waters seem to have had their deep curative application (Mantovanelli 2014; Bassani 2014). This article examines several of the most prominent and widely employed medicinal clays described in classical texts. Through the lens of contemporary mineralogical and geological knowledge regarding their probable provenance and genesis, the study investigates the historical foundations of the therapeutic properties attributed to these materials and evaluates the extent to which such claims find support in modern scientific understanding. The accent was placed on potential origin of these clays in hydrothermal environments known and utilised in antiquity for therapeutic purposes, considering how such geological settings may have shaped the ritual practices and cultural meanings associated with their use.

keywords | Medicinal clay; Hydrothermal source; Classical practices.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Mila Cvetkovic, Clay as cure. Medicinal and ritual uses of earths in classical antiquity, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 231, gennaio/febbraio 2026.