A gondola, a fishpond and, perhaps, a thermal bath

New evidence from Isola del Giglio

Enrico Maria Giuffrè, Jacopo Tabolli

Abstract

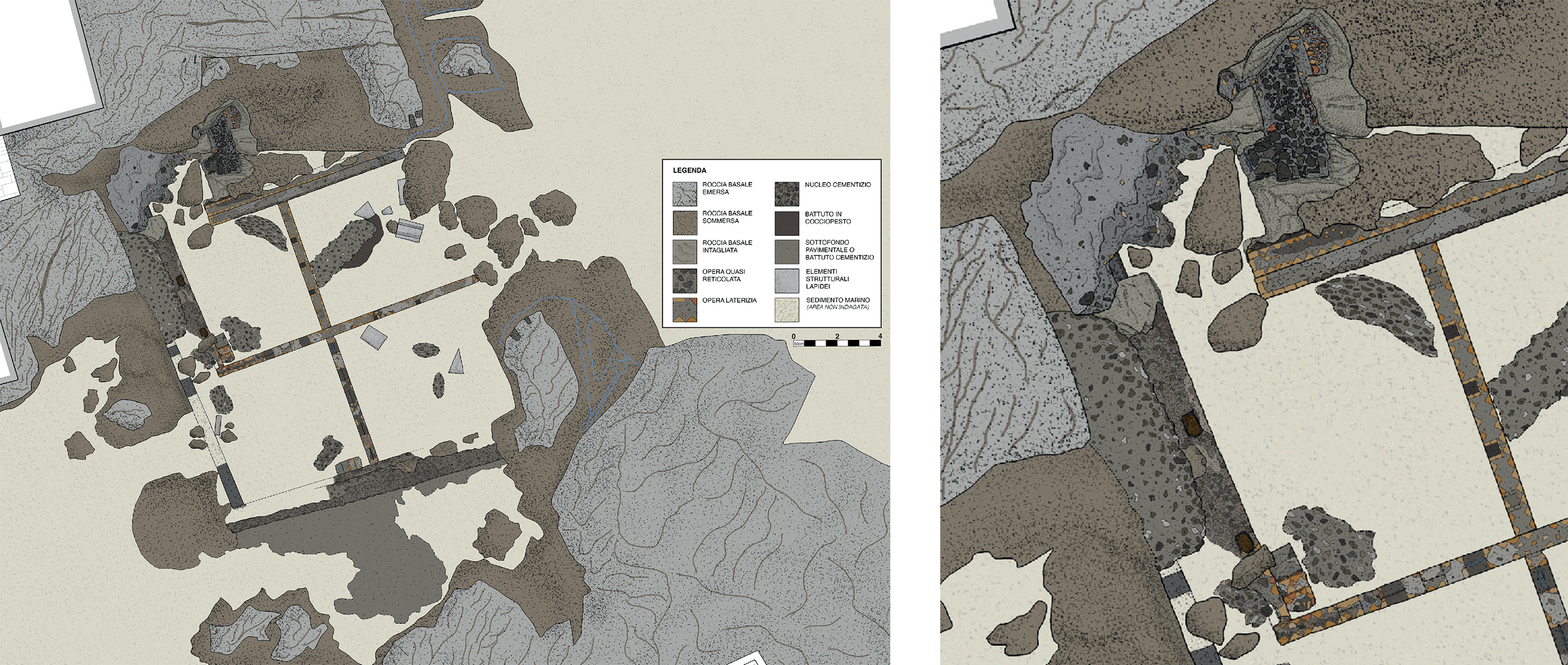

1 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Underwater excavation outlined on the general plan of the maritime villa, plan oriented towards the north (drawing and photo by J. Tabolli).

Excavation campaigns conducted between 2019 and 2021 at the Roman peschiera (fishpond) of Bagno del Saraceno in Giglio Porto (Tuscany, Italy) have, for the first time, allowed a systematic investigation of this submerged structure, carried out within the framework of the SEASCAPE project [Fig. 1] (Tabolli, Grimaudo 2022; Rendini, Tabolli 2023; Grimaudo, Tabolli forthcoming). Unlike the sole survey undertaken in the early Seventies (Schmiedt 1975), the new excavations have revealed multiple construction phases of the fishpond. In an earlier phase — possibly dating to the late 1st century BC and contemporaneous with the construction of the great western pier of Giglio Porto — a small landing installation was cut into the granite cliff at Bagno del Saraceno. This structure served the maritime villa (most recently Rendini 2022, with previous bibliography) immediately to the south, which was arranged on several terraces projecting over the sea. The deep cuts in the granite bedrock at Bagno del Saraceno remain clearly visible today and form a nearly rectangular basin, probably partially open to the east, toward the open sea. During the Neronian period, and in conjunction with the first major refurbishment of the maritime villa — when the complex was provided with the richly decorated terrace with anterides and the central block featuring a courtyard adorned with splendid frescoed wall revetments, mosaic pavements, and opus sectile flooring (Rendini 2016) — the original landing place was converted into a fishpond. This new installation consisted of four interconnected tanks, equipped with a system of perforated lead grilles [Fig. 2]. A small quadrangular chamber to the northwest, accessed by a descending staircase, clearly provided entry to the structure. Freshwater entered the complex from the west through what is now interpreted as the access channel to the tanks, which originally featured a closing mechanism adorned with columns. This water derived from the Bonsere valley, fed by a spring that is no longer active today. Historical records indicate that up to fourteen perennial springs once existed on the island of Giglio; at present, seven remain active, with modest and seasonally variable discharge. Additional minor seasonal or perched springs are also documented. The deeper groundwater circulation follows the island’s fracture system along relatively short pathways, with spring temperatures in the range of 15–18 °C — typical of non-thermo-mineral aquifers. Originating from the resurgences of the Foriano (Forano) quarry (Bruno 1998; most recently, Tabolli et al. 2019) — an area characterized by extensive colluvial deposits — the watercourse passed through the valley where the Roman darsena (harbour basin) is believed to have been located, along modern via dell’Asilo. It continued near the present-day School buildings before reaching the Bagno del Saraceno. It is therefore plausible that the admixture of freshwater from the valley with seawater produced the brackish conditions required for the operation of the fishpond attached to the large imperial maritime villa. The complex was probably restored during the late Hadrian period, when the masonry structures were consolidated using opus mixtum, and new sections of opus reticulatum were rebuilt. At the same time, the entire maritime villa underwent a major programme of reconstruction and repair. The large octagonal lighthouse, situated at the summit of Poggio dei Castellari and directly connected to the villa, also belongs to this phase, reflecting the recurrent villa–lighthouse association frequently observed in the ideology of imperial villas, particularly during the 1st century AD (Rendini 1999).

2 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Roman Fishpond. Final plan of the excavation, plan oriented towards the north (drawing by Rasta Divers). It is evident the south-west interruption of ancient structures corresponding to the access of fresh water into the fishpond.

3 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Roman Fishpond. Detail of the final plan of the excavation, with the north-west access, plan oriented towards the north (drawing by Rasta Divers).

Excavations conducted in the fishpond yielded a total of 550 isolated finds, many of them redeposited or washed in by marine action. These materials were identified either on the exposed surfaces of the detrital deposits or recovered during the excavation of several limited areas of the basin floor. The assemblage includes metallic objects — mostly of lead, but also of iron, bronze, and copper — alongside stone fragments, as well as ceramic, glass, and faunal remains. Portions of stucco and mortar bedding layers were also documented, together with iron concretions and small fragments of mineral deposits. In particular, the excavation conducted within the small north-western tank [Fig. 3], despite the presence of substantial accumulations and debris — partly resulting from the reuse of the western wall as a foundation for a telegraph structure with a platform up to the last century — brought to light a noteworthy deposit of predominantly metallic artefacts [Fig. 4].

4 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Roman Fishpond. Appearance of the deposit with lead elements. An anchor is visible (photo by G. Grimaudo).

At an upper stratigraphic level, an anchor was uncovered, and subsequent excavation phases revealed what clearly appears to be the hull of a vessel, found in association with a pseudo-triangular element designed to be fitted to the hull [Fig. 5]. Associated with this deposit were two semicircular decorative finials (similar to small helmets) and two serpentine elements. All of the finds were identified at the time of discovery as being made of lead. The presence within the same deposit of several modern depictions of towers enabled the assemblage to be interpreted as of modern date.

5 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Roman Fishpond. Detail of the lead anchor and hull (photo by G. Grimaudo).

Nevertheless, the hull itself appears to belong to an entirely ‘exceptional’ piece, considering the provenance and the context [Fig. 6]. The hull measures 32 cm in length and 4.5 cm at its maximum width. Near its ends, it curls upwards at two points, reaching a maximum height of 3.5 cm. While the outer base is flat, the interior is decorated in relief. In the area near the bow, a wooden planking pattern with rectangular panels is represented; in the central section, longitudinal planks are depicted; and in the distal portion, near the stern, the panels are filled with small circular motifs, followed again by longitudinal terminations that have been heavily abraded by seawater.

6 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Roman Fishpond. The lead hull (photo by Rasta Divers).

The interlocking element is decorated in imitation of wooden carving and displays, in its lower portion, a stepped profile. Although at first we hypothesised that the find might represent an ancient model of a Roman ship, it was Giulio Ciampoltrini who identified clear parallels with lead toys and inkwells depicting Venetian gondolas, widely produced between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The significance of this curious deposit of lead toys, discovered within the late sediments of the Roman fishpond, remains enigmatic. It may, however, be interpreted within the broader context of the mementoes and small objects that Giglio’s sailors are believed to have brought back to the island after long periods of service at sea. In this sense, the discovery not only provides insight into the later reuses and transformations of the ancient site, but also symbolically connects the maritime identity of the island’s modern seafarers with the enduring memory of its Roman maritime landscape.

7 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Roman Fishpond. Excavation phases with detail portraying a rectangular tubulus (photo by Rasta Divers).

8 | Isola del Giglio. Bagno del Saraceno. Roman Fishpond. Rectangular tubulus (photo by G. Grimaudo).

The continuation of the excavation, beneath the modern deposits, made it possible to identify abundant remains from the phases of abandonment of the fishpond, mixed with materials originating from the maritime villa located to the south and from the harbour structures situated to the west and north of the tanks [Fig. 7]. Numerous bessales were also recovered, attributable to the figlinae of the Domitii, although a substantial portion of the assemblage belongs to the production of Gobathus, given the notable diffusion of the stamps of T. Claudius Gobathus within the province of Grosseto (Gliozzo et al. 2020). An unexpected element within these stratigraphic levels was the discovery of several quadrangular tubuli (9 fragmentary ones, and one intact as in Fig. 8), characteristic of Roman structures equipped with water-heating systems, such as thermae and balnea. The presence of balnea associated with complexes that also included Roman fishponds is well attested and widespread — one may cite, for example, the balneum of Le Guardiole at Castrum Novum (Enei et al. 2016), or the Domitiana Positio itself (Ciampoltrini, Rendini 2023, with previous bibliography). However, at the conclusion of the 2021 excavation at Bagno del Saraceno, no structural remains were yet known that could be directly associated with the tubuli recovered from within the deposits of the fishpond.

J.T

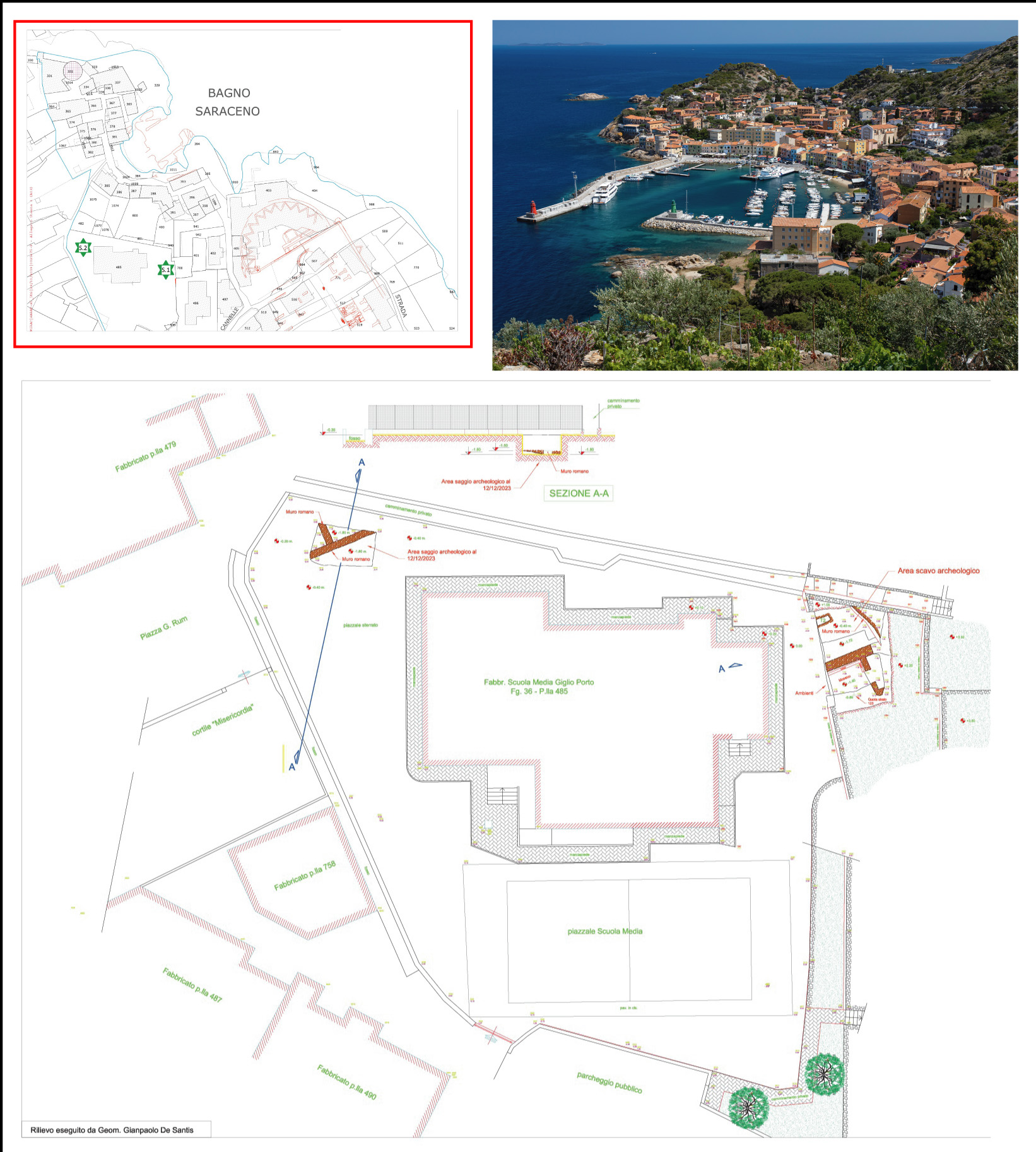

9 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Location of the two excavated areas close to the School, plan oriented towards the north (drawing by F. Lodovici).

Between November 2022 and December 2023, during a campaign of preventive archaeological investigations carried out in the locality of Giglio Porto, near the present-day R. Maltini School, new and highly significant remains of the Roman period came to light. These remains can be attributed to the above-mentioned large Roman complex of the villa del Saraceno, which once stood on Poggio del Castellare, overlooking and controlling the island’s harbour. The traces of this villa, scenographically overlooking the sea and continuously occupied from the late 1st century BC to the 4th century AD, are still visible today interspersed among the modern settlement — at the Bagno del Saraceno (the villa’s fishpond) — and further north, along the southeastern slope of the cliff, where an extensive system of cryptoporticus and terraces stretched up to the summit of the hill crowned by the octagonal lighthouse.

Descending toward the sea in the direction of the harbour from the central quadrangular core connected to the large lower terrace with a semicircular plan and anterides buttresses, embellished with mosaic pavements and opus sectile flooring, other structures were directly connected to the main villa, serving productive or utilitarian functions (Rendini 2007; 2022). Precisely on the terrace below the large semicircular hall, at less than 50 meters southwest of the Bagno del Saraceno, two distinct archaeological trenches revealed, on one side, at least two heated rooms (the better-preserved measuring approximately 4×3 m), equipped with suspensurae and a perimeter cavity with tubuli for the circulation of hot air (S.1); and on the other side, two additional rooms set at a slightly lower level and arranged orthogonally to a wide corridor (S.2) [Fig. 9]. These rooms can plausibly be interpreted as part of a balneum or thermal installation and the tubuli are identical to those found in the stratigraphic deposits in the peschiera.

The first trench, located further east, exposed a rather significant stratigraphic sequence composed of at least three burials — one within an amphora and two in trenches built in stone, and brick-lined graves — belonging to the late phases of the imperial complex, as attested by the types of amphorae employed [Fig. 10]. These burials, devoid of grave goods and consistently documented elsewhere within the complex, especially in the late phase of occupation, dating to the 6th and 7th centuries AD (Rendini 2022, with previous bibliography), cut directly into the abandonment layers of the heated rooms [Fig. 11].

Underneath the burials, the high construction quality of this sector of the complex — clearly connected to the imperial villa itself — is attested not only by the masonry technique, featuring a robust concrete core rich in pozzolana mortar and an external facing of blocks of varying size alternated with brick courses laid in roughly horizontal rows, but also, and above all, by the pavements in white mosaic tesserae bordered by a broad black band, and by marble crustae wall revetments found both in situ and within the obliteration layers [Fig. 12].

10 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Graves found at the excavation near the School (photo by F. Lodovici).

11 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Possibly the balneum close to the School with evidence of rectangular tubuli, plan oriented towards the north (photo and drawings by F. Lodovici).

12 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Details of the mosaics and use of marble (photo by F. Lodovici).

From these same levels, and on two still-preserved bipedales, several stamped brick fragments were recovered, bearing a characteristic crescent-shaped mark already known from earlier discoveries in the area (after Bronson, Uggeri 1970), dating to the first half of the 2nd century AD-between the late Hadrian period and the early years of the reign of Antoninus Pius. Additional finds include fragments of Italian and African sigillata pottery, several oil lamps, a bronze handle probably belonging to a jug, iron and lead nails, and a possible iron tap [Figg. 13–14]. The two rooms were directly connected on their short side by a marble threshold (57 × 98 cm) with two recesses — one rectangular, likely for a hinge, and the other semicircular on the opposite side — together with six small circular holes, two of which still contained lead-plugged nails [Fig. 15]. Another threshold, only partially visible during excavation, probably connected the eastern room, recently investigated, with the space immediately to the north. Although the excavated area remains relatively limited — and further investigation is currently hindered by the considerable overlying deposits — it nonetheless provides an interesting glimpse into the late Hadrian phase of the complex and its development toward the actual harbour district.

13 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Presence of Imperial stamps. Detail of underground suspensurae (photo by F. Lodovici).

14 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Artefacts discovered during the excavation (photo by F. Lodovici).

15 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Excavation of the heated room (photo by F. Lodovici).

16 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Second excavated area, with traces of plastered wall (drawing by F. Lodovici).

Proceeding westward, a second trench—opened immediately beyond the currently used school complex—exposed additional structures, including at least two orthogonal rooms aligned SW–NE along a perimeter wall, traceable for approximately 4.4 m in length and about 60 cm in thickness, constructed once again in opus caementicium with an outer facing of pseudo-regular blocks arranged in horizontal courses. Traces of wall plaster, up to 4 cm thick and composed of mortar mixed with cocciopesto, suggest that these rooms served a functional or service role within the broader complex [Fig. 16]. It is worth noting that these latter rooms lie at a slightly lower elevation than the thermal spaces to the east, and their floor level could not be reached for safety reasons. From their obliteration layers came numerous ceramic fragments — mainly African cooking ware and amphora sherds — together with brick pieces, cocciopesto fragments, and a few iron nails. The difference in elevation between the two groups of rooms described above may be explained by an additional terrace wall that likely connected the thermal level with a lower terrace corresponding to the villa’s peschiera. Although this retaining wall was not excavated directly, a pronounced linear anomaly oriented north–south, identified through a ground-penetrating radar survey conducted in the school courtyard, may represent its trace [Fig. 17].

E.M.G

17 | Isola del Giglio. Giglio Porto. Results of the geophysics survey (GPR) around the School (digital elaboration by ATS).

In conclusion, the combined results of the excavation campaigns carried out between 2019 and 2023 —first at the Roman peschiera of Bagno del Saraceno and subsequently in the area immediately to its south— offer, for the first time, a coherent and stratified picture of the lower sector of the villa del Saraceno, revealing the complex articulation of its maritime front. The new evidence not only refines the understanding of the villa’s structural layout and chronology but also illuminates the functional and hydraulic interconnections between its residential, productive, and leisure components. The discovery within the peschiera deposits of several tubuli — quadrangular hollow tiles typical of wall-heating systems — anticipated the later identification (although from a context with modern material associated) less than fifty metres to the southwest, of a series of heated rooms equipped with suspensurae and tubuli for the circulation of hot air. The identical typology of these architectural elements, the presence of the same stamps, leaves little doubt as to their association, strongly suggesting that the possible baths (balneum) discovered near the modern School were functionally and structurally linked to the fishpond complex. This connection is further supported by their shared orientation, the gradual terracing of the terrain descending toward the sea, and the hydraulic logic of the installations, which exploited the natural flow of freshwater descending from the Bonsere valley.

Taken together, the evidence delineates an articulated sequence of terraces descending from the residential nucleus of the villa to the maritime structures on the shoreline. At the intermediate level lay the balneum, elegantly decorated with mosaic pavements and marble revetments, while at the lowest terrace the peschiera combined practical and symbolic functions — serving both as a fish-breeding installation and as an element of aesthetic display in the maritime façade. The integration of these features mirrors a widespread pattern in the design of imperial villae maritimae, where the control and enjoyment of water-whether fresh, brackish, or marine — played a central role in shaping the architecture and the ideological representation of leisure and power. The Hadrianic reconstruction phase, now securely attested both in the thermal complex and in the masonry of the peschiera, marks a moment of comprehensive renewal in the life of the villa, paralleled by the construction of the octagonal lighthouse on the summit of Poggio del Castellare. This monumental alignment — from the upper residential quarters to the baths and the fishpond below — embodies the characteristic unity of landscape, architecture, and seascape that defined the Roman conception of the villa maritima.

Beyond its architectural significance, the close correspondence between the stratigraphic, structural, and material data recovered from these two excavation areas confirms the exceptional state of preservation of the complex and underscores the importance of these recent investigations. Even the curious discovery of a small lead “gondola” — a modern object later redeposited within the ancient peschiera — serves as a poignant reminder of the site’s enduring maritime vocation and of the symbolic continuity that links the island’s modern seafarers to its Roman past. The coordinated study of the peschiera and the balneum thus not only advances our knowledge of the villa del Saraceno but also contributes to a broader understanding of the management of water, space, and sensory experience in Roman coastal villas of the Tyrrhenian region.

E.M.G, J.T

We would like to thank our friends and colleagues with whom we have discussed our research during the preparation of this contribution; and in particular, Giulio Ciampoltrini, Giuseppina Grimaudo, Flavia Lodovici, Helga Maiorana, Paola Rendini.

Bibliography

- Bronson, Uggeri 1970

R.C. Bronson, G. Uggeri, Isola del Giglio, Isola di Giannutri, Monte Argentario, Laguna di Orbetello, “Studi Etruschi” 38 (1970), 201-214. - Bruno 1998

M. Bruno, Isola del Giglio, la cava di granito del Foriano presso Giglio Porto, in P. Pensabene (a cura di), Marmi antichi II: cave e tecnica di lavorazione, provenienze e distribuzione (Studi Miscellanei, 31), Roma 1998, 119-143. - Ciampoltrini, Rendini 2023

G. Ciampoltrini, P. Rendini, Il Portus Cosanus nella prima età imperiale. Strutture portuali per i traffici del Tirreno centro-settentrionale fra fine del I secolo a.C. e I secolo d.C., in M. Urteaga, A. Pizzo (eds), Entre Mareis. Emplazamiento, infraestructuras y organización de los puertos romanos, Roma 2023, 187-196. - Enei et al. 2016

F. Enei, S. Nardi-Combescure, G. Poccardi, V. Cicolani, Castrum Novum (Santa Marinella, prov. de Rome), “Chronique des activités archéologiques de l’École française de Rome” (2016). - Gliozzo et al. 2020

E. Gliozzo, P.L. Fantozzi, C. Ionescu, Supplementary - Old recipes, new strategies: Paleoenvironment, georesources, building materials, and trade networks in Roman Tuscany (Italy), “Geoarcheology an international journal” Vol. 35, 5 (2020). - Grimaudo, Tabolli forthcoming

G. Grimaudo, J. Tabolli, La peschiera romana e le colonne sommerse di Giglio Porto: prime indagini subacquee e considerazioni archeologiche preliminari, VII Convegno Nazionale di Archeologia Subacquea (La Maddalena, 11-14 maggio 2023), forthcoming. - Rendini 2007

P. Rendini, Giglio e Giannutri: novità (e conferme) sulle pavimentazioni di età romana, “AISCOM” 12 (2007), 167-178. - Rendini 2009

P. Rendini, I fari antichi di Giglio e Giannutri. Un aggiornamento, in C. Marangio, G. Laudizi (a cura di), Palaià Philìa. Studi di topografia antica in onore di Giovanni Uggeri, Galatina, Roma 2009, 389-396. - Rendini 2016

P. Rendini, La villa romana di Giglio Porto (Isola del Giglio): la decorazione parietale, in F. Donati (a cura di), Pitture murali nell’Etruria romana: testimonianze inedite e stato dell’arte. Atti della Giornata di Studi (Pisa 2015), Pisa 2016, 65-73. - Rendini 2022

P. Rendini, L’isola del Giglio e le rotte bizantine in età longobarda (VI-VII secolo), in C. Valdambrini (a cura di), Una terra di mezzo. I Longobardi e la nascita della Toscana, Catalogo della mostra Grosseto 2021, Cinisello Balsamo 2022, 397-407. - Rendini, Tabolli 2023

P. Rendini, J. Tabolli, Novità sul sistema portuale romano di Giglio Porto: dialoghi tra seascape e la tradizione di tutela e ricerca sul porto, in M. Urteaga, A. Pizzo (eds), Entre Mareis. Emplazamiento, infraestructuras y organización de los puertos romanos, Roma 2023, 197-206. - Schmiedt 1975

G. Schmiedt, Antichi porti d’Italia, Firenze 1975. - Tabolli, Grimaudo 2022

J. Tabolli, G. Grimaudo, Attorno al relitto arcaico di Campese all’Isola del Giglio: dal diario di bordo del progetto Seascape, in F. Cavulli (a cura di) Come opera Federico sul campo, “Quaderni della Scuola di Specializzazione”, in “Beni Archeologici dell’Università di Napoli Federico II” (2022), 317-338. - Tabolli et al. 2019

J. Tabolli, M. Colombini, G. Grimaudo, Sbarcando al Giglio (GR): La ripresa delle indagini archeologiche a Giglio Porto a terra e in mare, “Bollettino di Archeologia on line” 10 (2019), 3-4, 31-41.

Abstract

Between 2019 and 2021, excavation campaigns at the Roman peschiera (fishpond) of Bagno del Saraceno in Giglio Porto, carried out within the SEASCAPE project, provided the first systematic investigation of this submerged complex. The research revealed multiple construction phases, beginning with a late 1st-century BC landing installation hewn into the granite cliff and associated with the nearby maritime villa. During the Neronian period, this structure was transformed into a fishpond of four interconnected tanks supplied with freshwater from the Bonsere valley, which created the brackish environment necessary for fish farming. A late Hadrianic restoration phase saw the consolidation of the masonry in opus mixtum and opus reticulatum, contemporaneous with the reorganisation of the villa and its octagonal lighthouse on Poggio dei Castellari. Excavations yielded over 550 finds, mostly metallic artefacts, alongside ceramics, glass, stucco, and faunal remains. Among these, a remarkable lead model resembling a gondola, probably a late eighteenth- or nineteenth-century toy, was found within the fishpond sediments, testifying to later reuse of the site. Beneath the modern deposits, layers associated with the abandonment of the complex contained bessales from the figlinae of the Domitii and Gobathus, as well as quadrangular tubuli indicative of heated-water installations, suggesting possible connections between the fishpond and now-lost balnea within the villa’s maritime sector. Excavations carried out in 2023 and 2024 brought to light, beneath the modern school buildings, mosaic-paved rooms with suspensurae and tubuli similar to those found in the fishpond of Bagno del Saraceno. It is not yet certain whether these remains represent a balneum annexed to the fishpond or rather a section of the large maritime villa itself.

keywords | Isola del Giglio; Bagno del Saraceno; Roman Fishpond; Lead models of gondolas; Balnea and fish-tanks.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: E.M. Giuffrè, J. Tabolli, A gondola, a fishpond and, perhaps, a thermal bath. New evidence from Isola del Giglio, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 231, gennaio/febbraio 2026.