Enhancing to preserve

The archaeological area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme (PD)

Paolo Faccio, Silvia Scordo

Abstract

I. Historical-Critical Survey of the Site

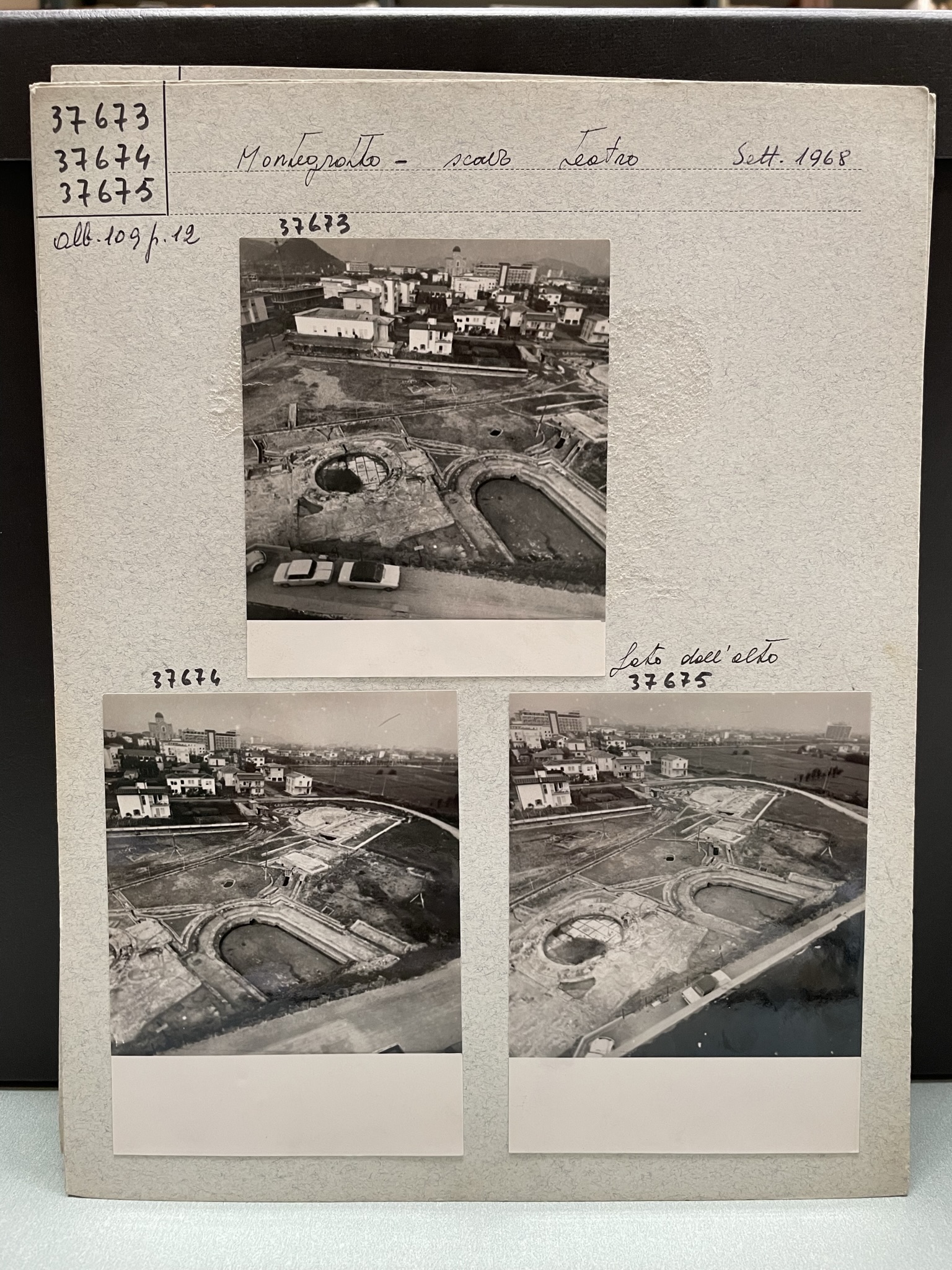

1 | Hypothetical reconstruction of the Roman Thermal Park at Montegrotto Terme (PD), showing the three main pools, the covered circular pool, the theatre/odeum, palaestrae, and water-lifting norias. Reconstruction based on archaeological evidence and surveys conducted by SABAP – Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio of Padua.

The archaeological area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme represents one of the most significant ancient thermal sites in the Veneto region, owing to the presence of hot springs and natural resources that facilitated human settlement as early as the Iron Age (Capuis 1993; Guidi 1992). The site reached its peak development during the alliance between the Romans and the Veneti (49 BC), when a large-scale thermal complex was established and remained active between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD. This complex included three pools (including a covered circular pool), an intricate network of channels, and two water-lifting norias, as well as recreational spaces such as palaestrae and a small theatre/odeum (Bonomi, Malacrino 2012) [Fig. 1].

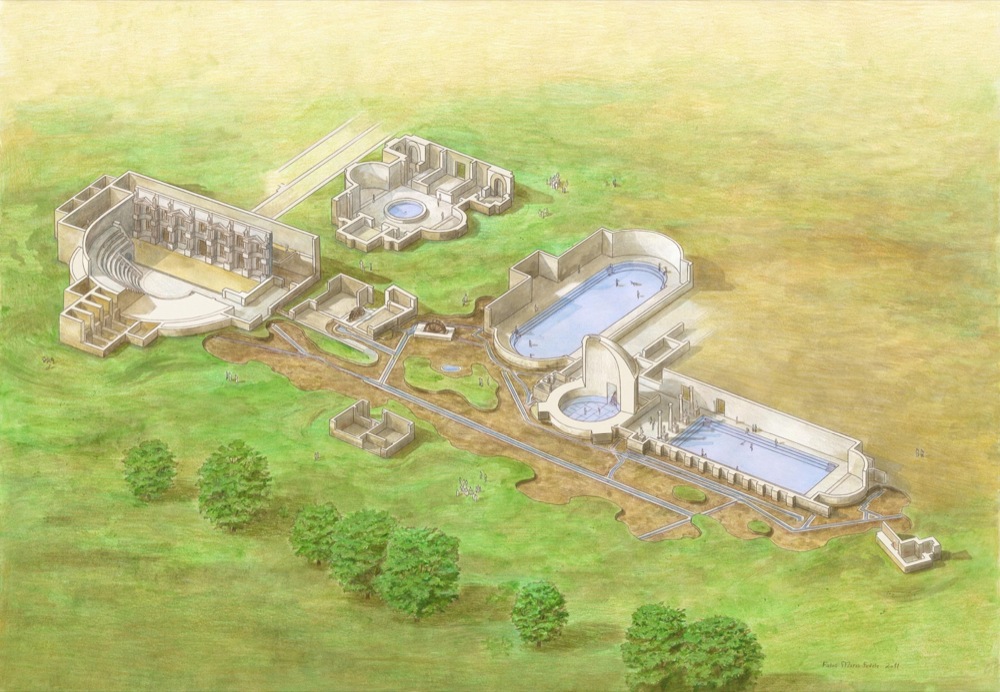

The theatre, a rare feature in a thermal complex, comprised a cavea, a semicircular orchestra, a stage with an architectural backdrop, and various service rooms. Like the rest of the complex, it was richly decorated with marble, stucco, and frescoes. Surrounding the baths, commercial activities thrived, linked to the flow of visitors (Zanovello 2012; Bassani 2025). Following the Roman period, the site was gradually abandoned, used as a quarry, and eventually overgrown by vegetation. Early evidence of its rediscovery dates to the late 18th century (Mandruzzato 1789-1804; Basso Peressut 2012), but systematic excavations only began in the 1960s, uncovering the pools, channels, and theatre. Between 1965 and 1985, restoration and structural protection works were carried out, initially using cement covers, followed by more precise recompositions and consolidation measures (Bassani 2022). In the 1990s, a temporary metal covering was installed over the odeum, which today is insufficient and requires replacement (Bonomi, Faleschini 2011). The odeum remains the best-preserved portion, with foundational structures still legible. However, many areas remain exposed to the elements and lack accessible internal pathways, making new interventions for protection, enhancement, and accessibility necessary [Fig. 2].

II. Planning Framework, Funding Strategies, and Critical Issues of the Via Scavi Archaeological Area: State of the Art and Initial Project Actions

2 | Superintendency of Padua, aerial view of the Via Scavi archaeological site, Montegrotto Terme, 1968. SABAP Padua, photographic archive ALB.109-p.12, nos. 37674 and 37675_a. The image shows the Roman thermal complex, highlighting the arrangement of pools, the theatre/odeum, and surrounding structures, serving as a key reference for later excavations and conservation interventions (Bonomi, Malacrino 2012; Bassani 2022).

The design and planning process was marked by lengthy development and approval phases, partly due to the succession of technical and administrative officers within the Superintendency. These timeframes are closely linked to the continuity of the Superintendency’s design and management strategies. Indeed, the project, which eventually reached a definitive stage of development, took shape under the direction of the Superintendent Dr. F. Magani, in collaboration with the Responsible Single Officer for the Procedure (RUP), Architect Silvia Scordo. This phase was followed by a subsequent approach oriented toward strengthening archaeological investigation and research, carried out under Dr. Tinè in collaboration with the archaeologist Maria Cristina Vallicelli. This process is currently continuing under the guidance of the Superintendent Dr. M. Mazza, within the framework of a progressive integration of conservation, research, and enhancement activities of the site.

For the year 2021, a total amount of €1,259,600.00 was allocated for the restoration and protection of the archaeological structures and for the implementation of new access and visitor facilities at the archaeological area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme. This allocation followed the preparation of the programme planning sheet drafted by the Project Manager (RUP), architect Silvia Scordo, of the Superintendency of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape of Padua, formally appointed on 24 January 2022 (Prot. no. 2006-P). The proposal was submitted pursuant to Article 1, paragraphs 9 and 10, of Law no. 190 of 23 December 2014, establishing the Cultural Heritage Protection Fund, intended to finance large-scale interventions on public cultural heritage, including non-state-owned assets, not covered by ordinary programming, with the aim of safeguarding and enhancing Italian cultural heritage (Ministry of Culture, Guidelines for the Protection and Enhancement of Cultural Heritage, 2017).

The budget was defined on the basis of the available documentation and subsequently recalibrated. The resources, required to initiate the first enhancement actions for the archaeological site within the 2021 programming framework, were approved by Ministerial Decree of 16 December 2021 (Rep. no. 450), Chapter 8099, P.G. 1, Fiscal Year 2021, CUP F65F21002250001. Following the approval of the overall funding, the financial resources were phased on an annual basis, allocating €100,000.00 in 2022 (Lot 1) and a further €100,000.00 in 2023 (Lot 2), in order to develop the different design stages and to carry out the necessary conservation interventions (DPCM 2021–2023).

This distribution made it possible to prepare the essential elements for the execution of works in subsequent years, optimising the use of available capital (Bondini 2020) and enabling more accurate long-term planning, also instrumental to the application for additional funding (Court of Auditors 2020). Following an assessment of the site’s needs and critical issues, the Superintendency decided to entrust an external professional firm with design development and consultancy tasks. This decision was formalised through Technical Report no. 15-PD of 17 November 2022, pertaining to Lot 2 – Archaeological Area of Via Stazione / Via degli Scavi, with a budget of €100,000.00. After reviewing curricula vitae, assessing the submitted bids, and identifying the proposal offering the most advantageous discount rate, the Superintendency awarded the contract to Faccio Engineering s.r.l. The appointment was formalised through Contract Rep. no. 322/2022, following a comparative evaluation of the received offers. With the urgent service handover report, signed on 7 December and officially recorded on 13 December, the first on-site inspections were initiated. The prompt commencement of these activities was necessary in order to coordinate the design process already underway by technicians appointed by the Municipality of Montegrotto Terme for the redevelopment of Viale della Stazione – an intervention affecting the southern edge of the archaeological area – with the project entrusted by the Superintendency to Faccio Engineering s.r.l.

This coordination between the archaeological project and the redevelopment of Viale della Stazione proved particularly urgent, as one of the site’s main criticalities concerns precisely the relationship between the archaeological area and Viale della Stazione, a major urban axis heavily frequented by both residents and tourists (Rinaldi 2022). Although the approximately 1.5 m difference in elevation provides a direct visual connection with the archaeological area, the distance between the road alignment and the core of the thermal complex causes the park to be perceived as an enclosed and poorly accessible space, with significant limitations in its integration into the urban fabric (Publio 2017). This difficulty in establishing a relationship with the avenue forms part of a broader framework of vulnerability affecting the current condition of the archaeological park. The excavations at Montegrotto represent a rare example of Roman thermal architecture (Bonomi, Malacrino 2012), with the three main pools today readable only at the level of their foundations, preserved within an area that constitutes a true void within the dense contemporary urban fabric (Ghedini et al. 2015).

The park is enclosed between the highly central Viale della Stazione, characterised by intense commercial activity, a residential area, and the imposing Hotel Montecarlo, currently abandoned (Santi 2021). Despite the central and potentially strategic location of the archaeological remains, the site lacks an adequate system of access and visitor services: the entrances from Via Scavi are devoid of reception areas and appropriate paving, and ticketing facilities, offices, and restrooms are entirely absent.

Internal circulation is equally problematic: there are no structured pathways, the grass-covered ground limits accessibility for many categories of visitors, and public use relies on provisional barriers that fail to guide movement or interpretation (Carbonara 2004). Further compounding these issues is the critical condition of the temporary covering of the theatre, which is now deteriorated and ineffective in protecting the ancient masonry, while also undermining the overall perception of the site (Laurenti 2006).

The site is therefore under-enhanced and in need of urgent maintenance works, as well as a comprehensive rethinking of accessibility, both from the urban context to the park and within the park itself (Ministry of Culture – Directorate General for Museums, Guidelines for Archaeological Parks, 2020).

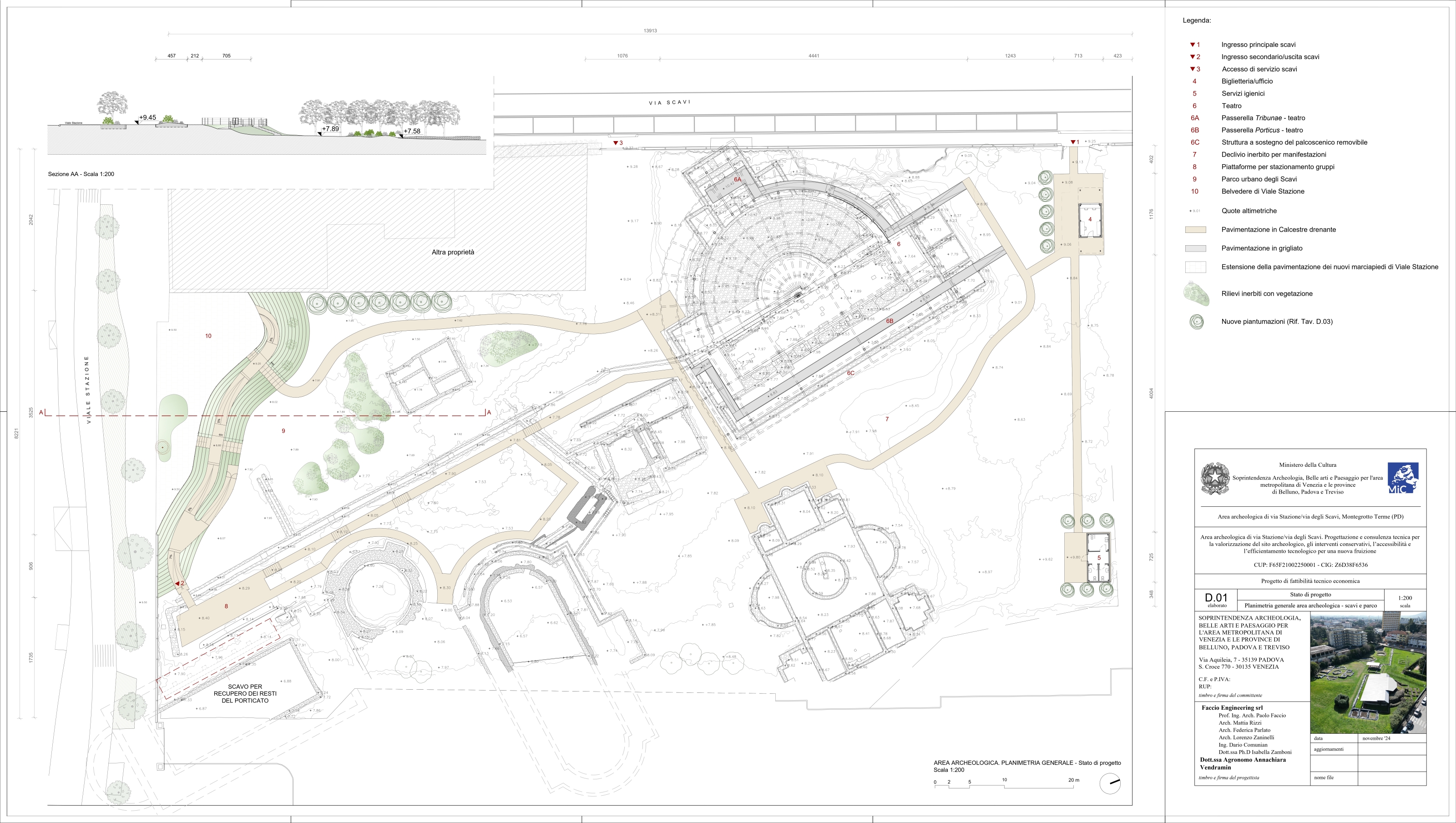

The urgently initiated inspections must be understood within this framework: ensuring that the redevelopment of Viale della Stazione and the enhancement project for the archaeological park proceed in a coordinated manner is an essential condition for overcoming the identified criticalities and for restoring the thermal complex to the role it deserves at the heart of the city. The difficulty of integrating extensive archaeological areas into the contemporary urban fabric without reducing them to “residual voids” or purely contemplative spaces reflects an issue widely discussed in recent disciplinary debate (Manacorda, 2007; Bandarin, van Oers 2012). This condition calls for design approaches capable of reconciling conservation requirements with active use and urban legibility, promoting the archaeological site as a recognizable and integral component of the city (Settis 2014) [Fig. 3].

3 | Superintendency of Padua, view from Viale della Stazione towards the Via Scavi archaeological area, Montegrotto Terme, 2020. SABAP Padua photographic archive. The southern access to the archaeological park is visible in the foreground; in the background, the Palazzo del Turismo, an unused provincial building in decay, highlights urban integration challenges adjacent to the Roman remains.

III. The definitive project level

The architectural project is deliberately positioned within the framework of the debate on integrated conservation and the architectural interpretation of archaeological heritage, conceiving contemporary design not as a neutral or mimetic element, but as a critical tool capable of making historical stratifications legible and of guiding public use and interpretation (Brandi, 1963; Carbonara, 199).

The project proposed for the archaeological area addresses the issues identified during the preliminary analysis phase, in line with the Client’s requirements and by adapting the site to a new mode of use and public enjoyment (Carandini 2010; Zanchetta 2018). A primary and fundamental aspect is the internal accessibility of the site: given the limited height of the remains of the pools and other thermal buildings, it is necessary to allow visitors the closest possible approach to the structures, not only to provide an overall perception of the thermal complex, but also to enable an interpretation of the historical uses of the various architectural elements (Brogiolo 2006; Guidi 2015). For a complete and safe visit, the project also proposes a predefined “museum-like” itinerary, guided by the architecture itself (Fowler 2013).

The main tourist entrance is located at the north-western access, where visitors are welcomed into a paved resting area shaded by tree planting (Pinto 2019). Here, a ticket office is redesigned, including space for a small administrative office, housed in a contemporary volume of steel and timber; a short distance away, a separate volume accommodates the restroom facilities (Montanari 2020).

The first itinerary begins with the visit to the remains of the Roman theatre, via walkways that allow internal circulation within the structure (Sear 2006). The theatre is equipped with a protective covering that highlights its former articulation and is configured as a semi-circular velarium, flanked by additional flat roof elements (Milesi 2017). One of these, corresponding to the pulpitum, the installation of photovoltaic panels will ensure the site’s energy autonomy (De Santoli 2014).

The covering is designed both to protect the theatre and to evoke its original spatial dimension, through a stable and durable structure that also enables the creation of elevated internal circulation paths, currently inaccessible (Choay 1992). The new route includes an asymmetrical walkway around the cavea, leading to a privileged central platform aligned with the tribunal seating. Beyond the clearly recognizable cavea, the theatre also includes a series of scenic and service spaces that cannot be perceived by visitors without appropriate enhancement and interpretation (Zanini 2015). The project therefore proposes a structure capable of addressing all these needs, while evoking – through its form – the ancient functions originally associated with the building (Settis 2002).

4 | Superintendency of Padua, definitive project for the Via Scavi archaeological area, Contract Rep. 322/2022, 2022. SABAP Padua works archive. The project highlights the north-western square as a welcoming hub and the south-western entrance with views from Viale della Stazione and a green space for visitors, alongside internal paths, the theatre/odeum, and the thermal structures.

As anticipated, the theatre covering is conceived as a ‘modern velarium’, recalling the form of Roman amphitheatre awnings and their sense of lightness through a roof skin composed of tapered steel slats, supported by a solid steel framework. This consists of slender, limited supports, strategically positioned to avoid interference with historic masonry as much as possible (Guidobaldi 2019). The theatre could ultimately resume hosting small-scale events, in a position symmetrical to the original, through the installation of a support structure for a removable stage measuring 6 × 4 m, located in correspondence with the postscaenium. A small audience area could be arranged on the gentle grassy slope east of the odeum (Pugliese Carratelli 2000).

Once past the theatre, the visit continues near the recreational building, then curves around the noriae, and subsequently approaches the thermal pools. At the final pool, a large resting area is created, as in other parts of the site, to accommodate individual visitors or groups (Greco 2012). All pedestrian pathways within the archaeological area are constructed in stabilised crushed limestone aggregate, a sustainable material that does not accumulate heat and is fully permeable (Caneva et al. 2011). The paths are 1.20 m wide and are developed without guardrails, reinforcing the concept of a trail unfolding within the archaeological park (Lynch 1960).

The visit concludes either by returning to the main entrance via a route parallel to the historic water channel, or through the secondary access on Viale delle Terme (Muratori 1959). This second access, opposite to the northern entrance, serves as the interface between the city and the archaeological area, integrating into the new Viale della Stazione. It is conceived as an extension of the avenue’s pedestrian zone, through a broad resting area at street level that offers visual access to the remains (Secchi 2013).

The change in elevation between the two spaces is resolved through a gentle slope, created by earth fill and supported by reinforced earth structures, upon which ramps and stairways provide vertical connections (Agnoletti 2011). The slopes are articulated by bands hosting evocative vegetation, selected based on plant species identified in the oldest stratigraphic layers of this and other archaeological sites in Montegrotto Terme (Rinaldi 2018). These include, for example, Bellis perennis, Centaurea cyanus, Linum usitatissimum, and Triticum durum, which contribute to evoking the historical atmosphere inevitably suggested by a visit to the excavations (Bertoncello 2004).

The design concept aims to allude – while fully respecting the monumental complex – to the ancient landscape in which the thermal park was originally embedded (Antrop 2005). Geomorphological investigations based on remote sensing and the analysis of historical cartography reveal a lacustrine-marshy landscape characterising the Montegrotto area, shaped by numerous thermal springs that generated pools and small watercourses (Camuffo 1997; Brogiolo, Forlin 2011). For this reason, several vegetated masses are introduced at the centre of the urban park, composed of Polygonum persicaria (Persicaria maculosa) and Arundo donax (common reed), evoking the presence of small thermal pools once widespread in this area and throughout the Montegrotto territory (Celant 2011). Owing to their morphological characteristics, these herbaceous species require minimal maintenance (Ferrari 2010) [Figs. 4-5].

5 | Superintendency of Padua, definitive project of the theatre/odeum, Contract Rep. 322/2022, 2022. SABAP Padua works archive. The project highlights the walkway across the cavea as the visitor route and the elevated path evoking the original forms, allowing close engagement and integrated understanding of the historic structure.

IV. Conclusion

The project aims to contribute to the disciplinary debate at the intersection of restoration theory and the enhancement of archaeological sites, demonstrating how the integration of architectural design, landscape, and light infrastructural systems can represent an effective strategy for the active conservation and cultural reactivation of urban archaeological contexts (Brandi 1963; Carbonara 1997; Manacorda 2007). From this perspective, the project is conceived as an open structure, allowing for the development of themes and design solutions in subsequent yet coordinated phases, and capable of accommodating future advancements in both valorisation and conservation strategies (Bandarin, van Oers 2012). The configuration of pathways and protective structures is designed to be adaptable to new archaeological discoveries and potential project extensions, thus reconciling site conservation with public accessibility and use (Manacorda 2007). At the same time, the project acknowledges certain intrinsic limitations related both to the fragmentary nature of the archaeological remains and to the constraints imposed by the densely built urban context. In particular, the decision not to reconstruct the original volumes of the thermal complex necessitates cautious design choices, oriented more toward spatial evocation than toward formal reconstruction, in line with established principles of contemporary conservation practice (Brandi 1963; Carbonara 1997).

Furthermore, the intervention is framed within defined financial and temporal parameters, which may nonetheless allow for future extensions of the project, including the implementation of advanced museographic devices, envisaged for subsequent phases of development (Bandarin, van Oers 2012).

Bibliography

Ministerial dataset and newspaper articles

- Corte dei Conti 2020

Corte dei Conti, Relazione sulla gestione dei fondi per la tutela del patrimonio culturale, 2020. - MIC 2017

Ministero della Cultura, Linee guida per la tutela e la valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale, 2017. - MIC 2020

Ministero della Cultura, Direzione Generale Musei, Linee guida per i parchi archeologici, 2020. - MIC 2021

Ministero della Cultura, Direttiva generale per l’azione amministrativa e la gestione, 2021-

Decreto Ministeriale MiC 16/12/2021, Rep. 450. - Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri 2021-2023

Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, DPCM Programmazione triennale lavori pubblici 2021-2023. - Rinaldi 2022

A. Rinaldi, Montegrotto, viale della Stazione cambia volto, “Il Mattino di Padova”, 2022. - Santi 2021

A. Santi, L’ex Hotel Montecarlo, una ferita nel centro termale, “Corriere del Veneto”, 2021.

References

- Agnoletti 2011

M. Agnoletti, The Conservation of Cultural Landscapes, Wallingford 2011. - Antrop 2005

M. Antrop, Why landscapes of the past are important for the future, “Landscape and Urban Planning” 70/1-2 (2005), 21-34. - Bandarin, van Oers 2012

F. Bandarin, R. van Oers, The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century, Hoboken (USA) 2012. - Bassani 2022

M. Bassani, L’edificio polilobato in Via Scavi a Montegrotto Terme. Ipotesi per una sua interpretazione, “Rivista di Archeologia” 46 (2022), 101-123. - Bassani 2025

M. Bassani, 2025, Adriatico salutifero, 1. Archeologia del termalismo al Fons Timavi e al Fons Aponi, Roma-Bristol 2025. - Basso Peressut 2012

G.L. Basso Peressut, The Archaeological Musealization: Multidisciplinary Intervention in Archaeological Sites for the Conservation, Communication and Cultur, Torino 2012. - Bondini 2020

A. Bondini, Il Mibact e gli investimenti per la cultura, “Aedon” 1 (2020), 29-40. - Bonomi, Faleschini 2011

S. Bonomi, F. Faleschini, L’incompatibilità e il degrado dei materiali di restauro nell’area archeologica di viale Stazione / via degli Scavi. Il caso del teatro, in M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae Patavinae, Il termalismo antico nel comprensorio euganeo e in Italia. Atti del I Convegno Nazionale (Padova 2010), Padova 2011, 57-64. - Bonomi, Malacrino 2012

S. Bonomi, C.G. Malacrino, Il complesso termale di viale Stazione / via degli Scavi a Montegrotto Terme, in M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae Patavinae, Montegrotto Terme e il termalismo in Italia. Aggiornamenti e nuove prospettive di valorizzazione. Atti del II Convegno Nazionale (Padova 2011), Padova 2012, 155-172. - Brandi 1963

C. Brandi, Teoria del restauro, Roma 1963. - Brogiolo 2006

G.P. Brogiolo, Archeologia dell’architettura, Mantova 2006. - Brogiolo, Forlin 2011

G.P. Brogiolo, P. Forlin, L’area archeologica di via Neroniana. Nota preliminare sulle fasi medievali, M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae Patavinae, Il termalismo antico nel comprensorio euganeo e in Italia. Atti del I Convegno Nazionale (Padova 2010), Padova 2011, 157-166. - Camuffo 1997

D. Camuffo, Microclimate for Cultural Heritage, Amsterdam 1997. - Caneva et al. 2011

G. Caneva, M.P. Nugari, O. Salvadori, La biologia delle superfici lapidee, Bologna 2011. - Capuis 1993

L. Capuis, I Veneti. Società e cultura di un popolo dell’Italia preromana, Milano 1993. - Carandini 2010

A. Carandini, Archeologia e progetto, Torino 2010. - Carbonara 1997

G. Carbonara, Avvicinamento al restauro. Teoria, storia, monumenti, Napoli 1997. - Carbonara 2004

G. Carbonara, Restauro Architettonico, Torino 2004. - Celant 2011

A. Celant, Fitodepurazione e paesaggi umidi, Roma 2011. - Choay 1992

F. Choay, L’allegoria del patrimonio [L’allégorie du patrimoine, Paris 1992], Roma-Bari 1992. - De Santoli 2014

L. De Santoli, Energia e sostenibilità negli edifici storici, Roma 2014. - Ferrari 2010

G. Ferrari, Flora spontanea e gestione ecologica del paesaggio, Firenze 2010. - Fowler 2013

D. Fowler, Museum Architecture and Exhibition Design, London 2013. - Ghedini et al. 2015

F. Ghedini, P. Zanovello, M. Bassani, E. Brener, C. Destro, T. Privitera, M. Bressan, La villa di Via Neroniana a Montegrotto Terme (Padova) fra conoscenza e valorizzazione, “Amoenitas” 4 (2015), 11-40. - Greco 2012

E. Greco, Archeologia e progetto contemporaneo, Roma 2012. - Guidi 1992

A. Guidi, Preistoria dell'Italia, Roma-Bari 1992. - Guidi 2015

G. Guidi, Manuale di rilievo archeologico, Pisa 2015. - Guidobaldi 2019

F. Guidobaldi, Architetture leggere per l’archeologia, Milano 2019. - Laurenti 2006

M.C. Laurenti (a cura di), Le coperture delle aree archeologiche. Museo aperto, Roma 2006. - Lynch 1960

K. Lynch, The Image of the City, Cambridge 1960. - Manacorda 2007

D. Manacorda, Il sito archeologico tra ricerca e valorizzazione, Roma 2007. - Mandruzzato 1789-1804

S. Mandruzzato, Dei Bagni di Abano. Trattato, 3 voll., Padova 1789-1804. - Milesi 2017

D. Milesi, Coperture contemporanee nei siti archeologici, Milano 2017. - Montanari 2020

T. Montanari, Il patrimonio culturale tra tutela e progetto, Torino 2020. - Muratori 1959

S. Muratori, Studi per una operante storia urbana di Venezia, Roma 1959. - Pinto 2019

L. Pinto, Architettura per l’accoglienza nei siti culturali, Firenze 2019. - Publio 2017

F. Publio, Il paesaggio urbano. Luoghi, significato e uso, Roma 2017. - Pugliese Carratelli 2000

G. Pugliese Carratelli, Teatri antichi e territorio, Napoli 2000. - Rinaldi 2018

S. Rinaldi, Vegetazione e paesaggi storici nell’Italia antica, Bologna 2018. - Sear 2006

F. Sear, Roman Theatres: An Architectural Study, Oxford 2006. - Secchi 2013

B. Secchi, La città dei ricchi e la città dei poveri, Roma-Bari 2013. - Settis 2002

S. Settis, Italia S.p.A.: l’assalto al patrimonio culturale, Torino 2002. - Settis 2014

S. Settis, Se Venezia muore, Torino 2014. - Zanchetta 2018

F. Zanchetta, Progetto e archeologia. Metodi e strumenti, Milano 2018. - Zanini 2015

E. Zanini, Archeologia dell’architettura e valorizzazione dei contesti monumentali, Roma 2015. - Zanovello 2012

P. Zanovello, Riflessioni sul comprensorio di Abano Terme, in M. Bassani, M. Bressan, F. Ghedini (a cura di), Aquae Patavinae, Montegrotto Terme e il termalismo in Italia. Aggiornamenti e nuove prospettive di valorizzazione. Atti del II Convegno Nazionale (Padova 2011), Padova 2012, 121-133.

Abstract

The contribution illustrates the new, comprehensive project for the conservation and enhancement of the archaeological area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme, made possible through dedicated funding allocated by the Ministry of Culture within Italy’s 2021-2023 public works programme. The intervention addresses structural vulnerabilities, the deteriorated protective systems, and the critical relationship between the archaeological park and the adjacent Viale della Stazione – one of the main urban thoroughfares. The proposed design redefines access points, introduces new visitor facilities, and creates a coherent, museum-like circulation system using sustainable materials. A major feature is the new permanent roof over the odeum, conceived as a contemporary velarium that ensures both protection and interpretative clarity while enabling elevated internal walkways and small-scale cultural events. The project also includes landscaped areas inspired by archaeobotanical evidence and geomorphological studies, evoking the ancient thermal and marshy environment of Montegrotto. Overall, the intervention aims to restore legibility, accessibility, and urban connectivity, offering a renewed framework for the public enjoyment and long-term preservation of this unique thermal heritage site.

keywords | Restoration; Valorization; Integrated Conservation and Technological Systems; Accessibility; Walkability; Landscape.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Paolo Faccio, Silvia Scordo, Enhancing to preserve. The Archaeological Area of Via Scavi in Montegrotto Terme (PD), “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 231, gennaio/febbraio 2026.