Chungking Crossing: Gio Ponti’s Forgotten Projects for Daniel Koo in Hong Kong (1963)

Emily Verla Bovino

English abstract

Introduction: Ominous Futures and a Speculative Present in Angry, Hungry Eyes

In 1996, less than a year before the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong from British to Chinese rule, reports about “violent crimes by illegal immigrants” in the city circulated in the international financial news (Stein 1996, A10). One headline from the Asian Wall Street Journal warned of “angry, hungry eyes” (Stein 1996, 1) across the border in mainland China, threatening redistribution of resources not for economic justice, but for resentful desiring of Hong Kong’s wealth. The alarm came from none other than controversial apparel and publishing mogul Jimmy Lai Chee-ying – founder of retailer Giordano and media group Next Digital – who to this day continues to be a constant presence in Hong Kong political news. In July 2020, Lai was charged by Hong Kong’s High Court with organizing and participating in unauthorized assembly related to anti-extradition and security law unrest (Wong 2020). Then, six weeks after the National Security Law was passed for Hong Kong by the central government in Beijing, Lai was arrested for “collusion with foreign forces” (Lo, Leung and Lau 2020). Police seized boxes of material in a raid of Apple Daily, Lai’s popular anti-government tabloid under Next Digital (Ibid). Characterized by “Xinhua”, the official state-run press agency of the People’s Republic of China as “an instigator of the Hong Kong riots” (“Xinhua” 2020) but as a high-profile “pro-democracy” figure by most international media (Ramzy and May 2020; Noack 2020; Shapiro 2020; Davidson 2020), Lai exemplifies the intersection between retail, wealth and political power in Hong Kong. Interestingly, however, a recent study on Hong Kong tycoons disqualified him from consideration as part of the ‘billionaire’ class because of his criticism of China: tycoons are generally understood as colluding with Beijing and the Hong Kong government (Hung 2016, 37).

The concluding image of doom in the same 1996 article headlined “Angry, Hungry Eyes” came in the form of a closing anecdote about another Hong Kong entrepreneur, this one more in line with the stereotype of the city’s tycoons, in league with the central government in Beijing and its supporters in the Hong Kong government. According to the report, earlier that year, seventy-three-year old department store magnate Daniel Koo Shing-cheong and his wife had been tied up by “three men believed to be illegal immigrants [from mainland China]” and were robbed for $16,000 in cash and valuables (Ibid). The article seems to imply that if Koo’s family was not safe, no family would be. The breach of a protected domestic environment is not explicitly mentioned in the article, only suggested; yet, the story is one of the rare times Koo’s residence in Tai Tam (1963), designed by Italian architect Gio Ponti, almost manages to make an appearance in a publication.

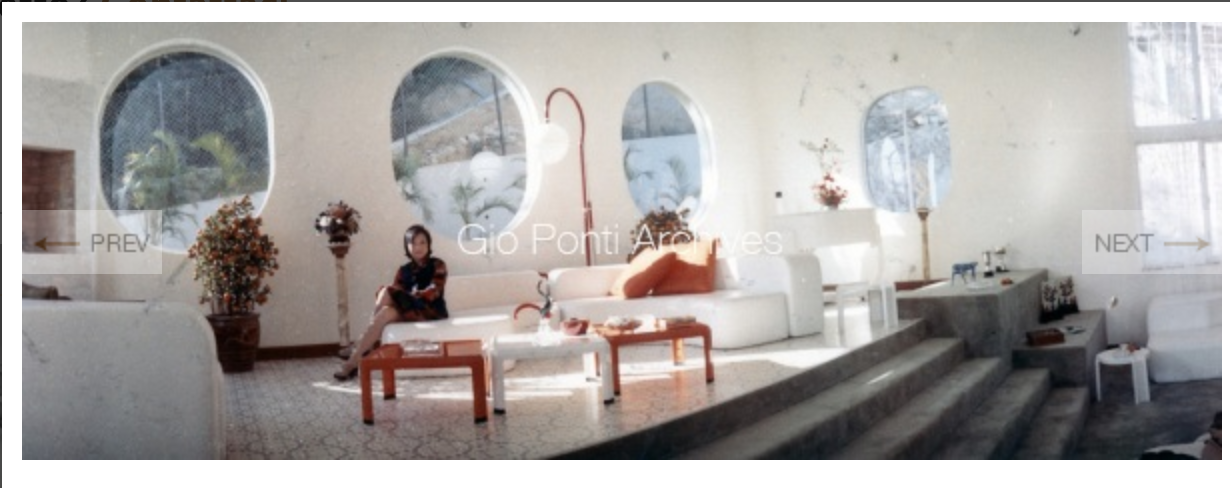

1-2 | Interior of Villa Koo with Koo Family member, possibly Daniel Koo Shing-cheong’s wife (top) and with Koo Family. Source: Gio Ponti Archives, nr. 266INT03.2, nr. 266INT02.

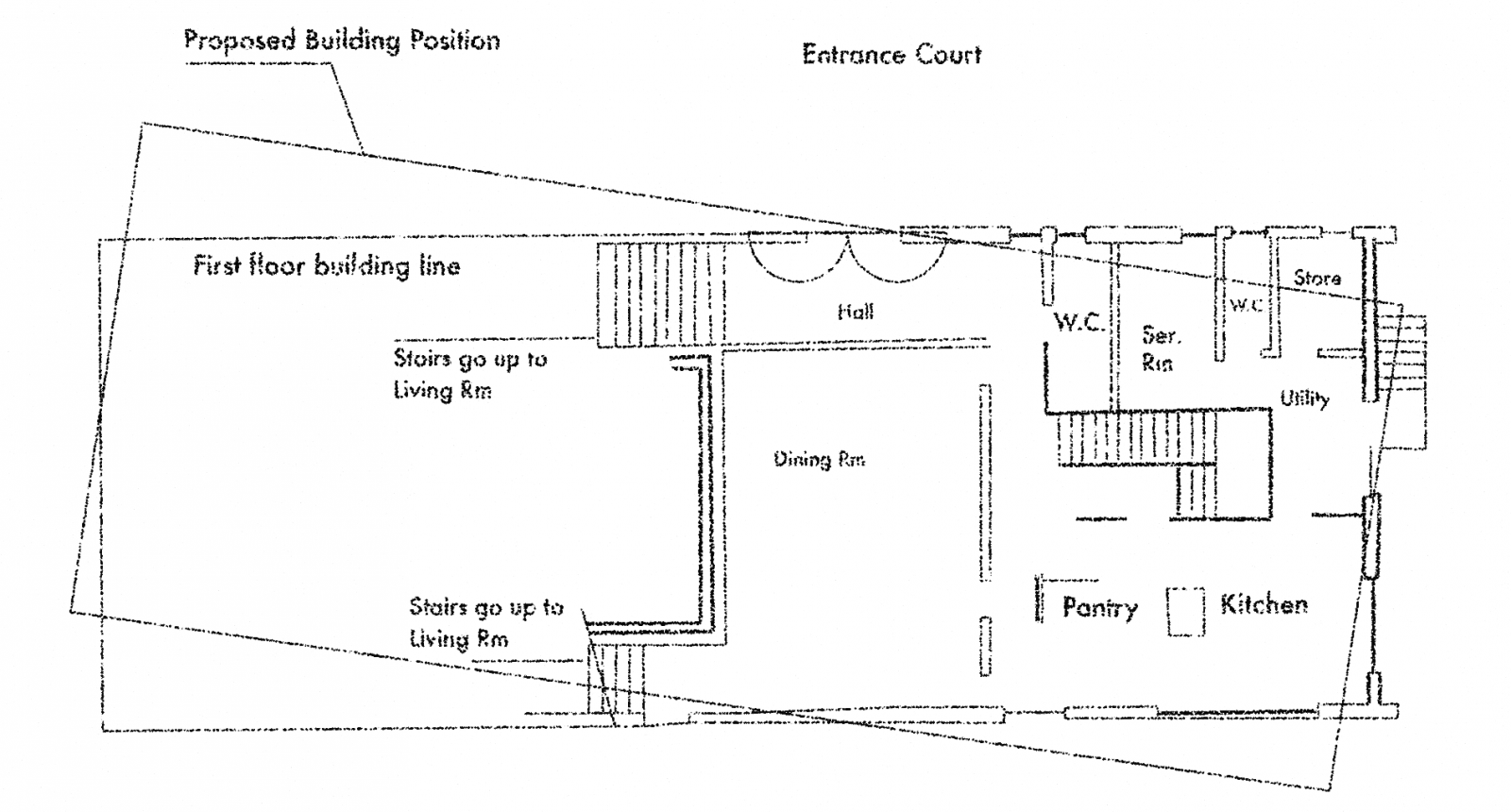

Along with Koo’s department store, Shui Hing [Fig. 3], also built in 1963, the Koo house, known in Ponti literature as “Villa Koo” [Fig. 1, 2], is one of two important projects by Ponti in Hong Kong, the former British colony now Special Administrative Region (Sar) of the People’s Republic of China. Though not necessarily determined by it, the limited bibliography for the house – only listed in literature on Ponti’s work as published in Japan’s Space Design in 1981 (Ponti 1990, 277) – reflects Hong Kong’s distress as a free port; the anxieties of capital accumulation the city was colonized to accommodate; the disquiet of precarity, neoliberalism’s entrepreneurial opportunity. Fortunes rise and fall quickly in Hong Kong. British imperial rule of the territory, once on the margins of the Qing Dynasty before the Opium Wars, had brought a new future for Koo’s father, Koo Shui Ting, a Mauritius Chinese merchant of Hakka descent (Lo 2017). Koo Shui Ting’s name continues to circulate in Hong Kong: in 1962, the Koo family donated funds to the University of Hong Kong that still finance an annual merit-based scholarship named in his honor. Shui Hing established in 1926 a small shop in Central District that grew until World War II-era Japanese Occupation forced contraction (Koo 1976, 13). With the Koo patriarch’s death just a year after the British return in 1946, his son Daniel Koo took on the family business (Ibid).

Between the 1950s and the 1960s, Koo’s activities developed Shui Hing in Kowloon with a strategy that situated its operations between the approaches of Chinese, Anglo-American and Japanese retailers (Ho 2002, 57). Koo made connections with ‘economic miracle’ Italy, which like Japan and Germany enjoyed exceptional growth after World War II, not in spite of but because of defeat and destruction (Scarpellini 2008, 126-127). In the 1990s, more mainland Chinese retailers entered the high-income market and the Japanese retailers who had dominated the 1970s were better positioned to answer the demand for higher quality merchandise than Hong Kong-Chinese companies; as a result, many of the older Hong Kong-Chinese retailers like Shui Hing eventually closed their retail businesses to invest in other sectors (Ibid, 81-82).

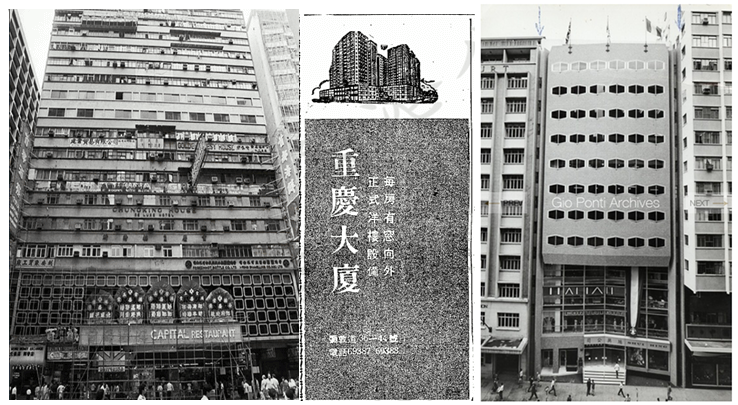

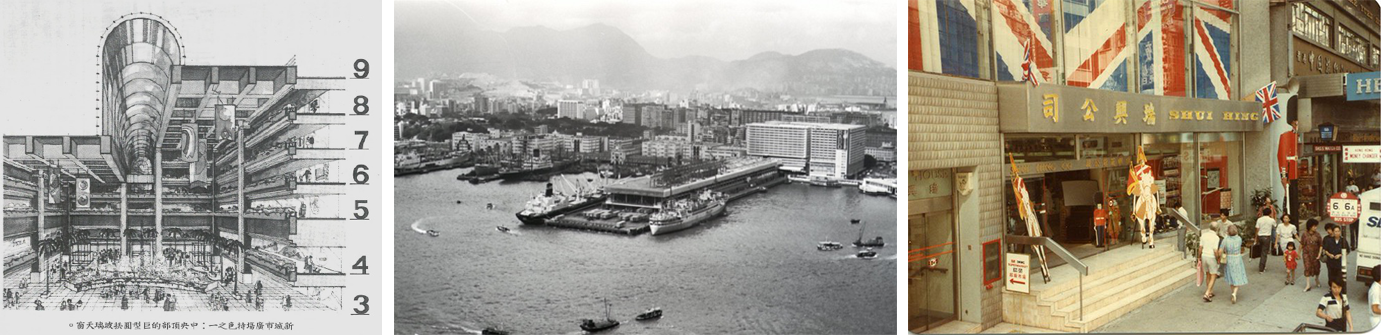

3 | The site on Nathan Road in Tsim Sha Tsui before the construction of Gio Ponti’s Shui Hing project in 1963; the Shui Hing project after construction. Source: Gio Ponti Archive, nr. 263EST03, 263EST02.

This essay discusses the two projects Ponti worked on for Koo: the forgotten Hong Kong villa in Tai Tam [Fig. 1, 2] and the neglected Shui Hing Department Store, now Prestige Tower, in Tsim Sha Tsui [Fig. 3] both built at a difficult time in the city. This was the period between the attempted electoral reform of the 1946 Young Plan, and the post-crisis social reforms following the 1967 leftist riots. The Young Plan, proposed by Hong Kong Governor Mark Young, aimed to remake the colonial state: the municipal council would be popularly elected through a system that would enfranchise more Chinese residents with decision-making power (Wong 2002, 108-109). The plan was never taken up.

The 1967 leftist riots, on the other hand, started as a local labor movement but ended with violence, deaths, and the reputation of having been instigated by mainland Communist infiltration (Yep and Bickers 2009, 14). Social reforms resulted, but were not aimed at changing the traditional colonial state; their goal was, instead, to secure British power to prepare negotiations with the People’s Republic of China and ensure good Sino-British relations (Ibid). Any efforts for electoral reform inspired by the Young Plan were abandoned. In light of recent political developments in Hong Kong, this history is important to recall for a clearer understanding of the city’s current struggles. Furthermore, the changes to the way consumption were imagined during this period align in a notable way with lost political opportunities. While the increased political enfranchisement imagined in the Young Plan never happened, from the 1960s on, the city was developed for more of its residents to have purchasing power and access to shopping (Mathews and Lui 2001, 9). At the same time, the conception of a “local Hong Kong identity” was taking shape among a population that had previously thought of itself as “sojourners, fleeing economic and political turmoil in mainland China” (Ibid, 10).

4 | Brigitte Lin playing ‘Woman in Blonde Wig’ in Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express (1994). Source: The Film Hermit.

The essay takes the title “Crossing Chungking” from Chungking Mansions (1961) one of Hong Kong’s most celebrated film locations, situated just across Kowloon’s Nathan Road from Shui Hing (now Prestige Tower). Made famous by filmmaker Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express (1994) [Fig. 4], Chungking Mansions is a composite building studied for ethnic, economic and social complexity that started to be developed in the 1970s, when the “middle-class Hong Kong and overseas Chinese buyers” to whom the buildings were originally marketed moved elsewhere and “new Chinese immigrants and South Asians” moved in (Seng 2020, 108 -109). With these transformations, its position as a central node in “low end globalization” has become the focus of studies (Mathews 2012, 70), along with its representation of Hong Kong’s “dual compression” – simultaneous global pressure and local pressure on the city’s population and environment (Huang 2004, 46).

Across the street, the Shui Hing Building [Fig. 5], a design of Harriman Realty Company for which Ponti was responsible for the façade and interiors, is a different kind of architecture produced by this “dual compression” (Ibid): the intensification of Hong Kong’s identity as what Keller Easterling calls a “logistics city” – “spaces of exemption” that “are also spaces of piracy, refugees, tax sheltering and labor exploitation,” thus also “the locus of global anxieties about security” (Easterling 2005, 100). “Compression” at Shui Hing-cum-Prestige Tower now literally manifests in the first four stories of the building. Originally conceived in split levels for open views onto several floors of merchandise from a main staircase (The Hong Kong and Far East Builder 1963, 114-116), the interiors are now subdivided into enclosures stocked with luxury brand apparel by various wholesalers [Fig. 5]. Likewise, it was “rampant subdivision” that in the 1980s, brought Chungking Mansions its reputation as a “problematic building” (Seng 2020, 110).

5 | Interior design of Gio Ponti’s Shui Hing project (1963, Tsim Sha Tsui) showing effect of the tapering ‘V’ shape beams with the lighting troughs marking the lowest point. Source: The Hong Kong and Far East Builder; present day interior of Shui Hing (now Prestige Tower) with subdivided areas for luxury brand wholesalers. Source: Emily Verla Bovino.

The oldest among the wholesalers occupying the premises is Donna Moda – part of a larger group with Della Moda and J.outlet, also in the building. Donna Moda advertises itself with a history, “founded in 1986” from a diamond jewelry wholesaler that started operations in 1981 (Donna Moda). “Hong Kong customers make up a minority of the company’s client base” its Facebook page informs visitors, “most wholesale clients are from mainland China” (Donna Moda).

In her recent book Resistant City (2020), Eunice Seng writes of Chungking Mansions [Fig. 6, left] as “manifest[ing] a moment in which speculative urban development under the colonial enterprise produced nuanced and fluid spatial associations” (Seng 2020, 115). As architecture aimed at fostering trade relationships through Hong Kong-Milan designs, experimenting with open interiors, surface textures, and relations between building and environment, Ponti’s Hong Kong department store and private house for Daniel Koo – though largely forgotten – are part of the same moment identified by Seng.

This essay begins and ends with Chungking Mansions [Fig. 6, left] to suggest that Koo’s Shui Hing [Fig. 6, right], and by association the Villa Koo, are the “political unconscious” (Jameson as quoted in Rendell 2011, 109) of architecture on Tsim Sha Tsui’s Nathan Road. In an approach that she calls “site-writing,” architecture critic Jane Rendell seeks ways to allow what literary critic Frederic Jameson calls “the tensions of class struggle” (Ibid 107) to emerge in architecture. At the centre of her method are what Freud called ‘intrusive ideas’ and ‘side issues’ that allow the writer and reader to follow the “setting […] which frames the provocation of transference” (Rendell 2011, 108). In this essay, Chungking Mansions provides an anchor for such a “setting.” The epilogue to the essay further comments on the process by which research came about, with the aim of setting off the reader’s own experiments with thinking through site-writing.

6 | Chungking Mansions (1961) on Nathan Road in Tsim Sha Tsui across from Gio Ponti’s Shui Hing project (1963). Source: The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group and Gio Ponti Archives, nr. 263EST05.

More than half a century before Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron designed glazed-ceramic and cast-aluminum envelopes for monumental buildings in Hong Kong’s cultural sector – the M+ Museum of Visual Culture (West Kowloon, 2020) and the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts (Central, 2018) – Ponti’s designs for Koo at both Shui Hing and Koo’s private home in Tai Tam were high-profile commissions that modestly experimented with materials in façade construction and cladding. Along with Norman Foster’s Hongkong Shanghai Bank (Central, 1983), Paul Rudolph’s Lippo Building (Central, 1986) and I.M. Pei’s Bank of China (Central, 1990), Ponti’s Shui Hing (Kowloon, 1963) was cited by at least one renowned colonial-era travel guide among the works of architectural merit from the latter part of the British colonial era, the only project of that group to be located in Kowloon (Morris 1989, 31). Though the architectural importance it was granted in the guide now seems rather inflated – perhaps only a result of the architect’s reputation – its status at the time may also be attributed to its renown as a shopping hotspot.

Poor maintenance and management devaluing its unique architectural features has facilitated its loss of status in recent years. As a showcase project aimed at boosting trade between Italy and Hong Kong, it can be considered formally important for its use of illumination, Italian ceramic tile and the floating façade-as-screen, as well as for the way that Ponti, near the end of his career, appears to look back to the early twentieth century Looshaus model for the high-rise department store (Austrian modernist Adolf Loos’s Goldman & Salatsch Building in Vienna, 1911) in the lead up to Hong Kong’s shopping mall urbanism. In Gio Ponti: Archi-Designer, Stefano A. Poli writes of the “prejudiced critique […] that weighed on Ponti” in the 1960s, the period he was working on the two Hong Kong projects: “he did not completely conform to the ideology of Italian architecture and was sometimes judged too inclined towards the charm of decoration” (Poli 2018, 252). Thus, the study of the two Hong Kong projects proposed here adds to more discussion of what Poli calls “Ponti’s unrecognized architecture” (Ibid).

The story of Villa Koo [Fig. 7], meanwhile, is not one of status lost, but never gained. As previously noted, there are few traces of the villa ever being substantially discussed in publications, perhaps because of concerns over its owner’s privacy and security, or because Ponti lacked enthusiasm for the project. Indeed, the Villa Koo is in no way comparable to houses like the Villa Planchart (1955) in Caracas, which Ponti considered to be among his most important works. And yet, on a smaller scale, there are aspects of Villa Planchart – built eight years earlier as part of broader efforts to modernize the Venezuelan city – that Ponti brought to Hong Kong, and the conversation that Villa Koo opened with client Daniel Koo eventually led into experimental drawings and plans for another house in San Francisco.

Moreover, the study of modernist villas in Hong Kong has mostly focused on the iconic Kadoorie Estate houses, post-war housing for elites built in the Kowloon hills by the Hong Kong Engineering and Construction Company (1937-1964) (Seng, Docomomo, 2020). Villa Koo is unique for the way Ponti worked with ceramic pebble cladding, an open split-level interior plan, staggered windows of different shapes and sizes, the experience of the interior, and emphasis on the landscape of Tai Tam.

This essay is thus an attempt to bring the two Italian-Hong Kong projects – products of what might eventually be further explored, through the use of materials and changing social significance of the buildings, as part of a broader partnership between the Mediterranean and Pearl River Delta regions – back into collective consciousness. It shows that Ponti’s Hong Kong projects are an important and underrated chapter in the history of Hong Kong modernism, both in their design and in their relationship to the city’s political history. It also argues that they represent an underappreciated moment in Ponti’s career and can be further studied to better understand Hong Kong’s impact on the design thinking of a visiting architect. Lastly, it focuses on the ways these two projects may encourage us to rethink discussions of housing, the use of space by cultures of consumption in Hong Kong, the politics of architect-client relationships, and the history of experiments with materials and typologies in Hong Kong architecture.

For an essay published in Engramma, a brief note to conclude this introduction is necessary to address how the essay’s methodology is inspired by work in Warburg Studies. In Aby Warburg’s art history of images, the Mnemosyne Atlas (1924-1929), prologue plate A is a configuration of images that suggest a basic framework for thinking about cultural history through symbolic, geopolitical and affective relationships: the cosmos (narratives about a culture’s understanding of its sensibilities and how it came to have them), migration (narratives about cultural migration and exchange across time and space) and genealogy (narratives of lineage and the politics of kinship). Prologue plates B and C demonstrate the way these relationships are internalized, mapped onto the body to become part of the individual and collective unconscious. Through the figure of the Zeppelin Airship in plate C, Warburg shows that architecture, with its close relationship to the body, is both a means to facilitate and to mitigate the socio-symbolic incorporation (Einverleibung) of the narratives it tells itself – more specifically, “how bodies achieve socio-symbolic dis-affection (or affective distance) by moving through subject and object positions in [what Warburg called] “incorporation” (Einverleibung), “corporal introjection,” (Hinein[Um]verleibung) “corporal annexation” (Anverleibung) and “corporal addition” (Zuverleibung)” (Bovino 2015, 32). In the last ten years, both the political unconscious of architecture (Lahiji 2011; Rendell 2017) and the client-architect relationship have been at the center of publications (Mautone 2009; Donchin 2013; Ferguson 2000), as has Hong Kong resistance and resilience (Seng 2020; Pang 2020; Yeh 2011). This essay writes through reading of these studies and is part of a continued work using observations from Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas prologue plates to write about cultural objects.

Villa Koo: The Non-Aligned Retreat or Sheltering Against Constraint and Coercion

Discussion of housing in Hong Kong tends to focus mostly on large-scale public and private housing estates in the city (Castells, 1986; Rooney 2003; Xue 2016; Lange and Carlow 2017). This focus is important, but it also distorts understanding of the built environment. The family house has an interesting and varied history in Hong Kong that challenges the suburb-slum dichotomy often repeated in contemporary studies on housing. Clusters of low and middle-income private residences and family homes – some the result of self-built, organic architecture and urbanism, sometimes ambivalent in legality, and almost always connected to complex histories of shifting land tenure – are contentiously present across Hong Kong, despite the preponderant clichés of the dense podium tower and subdivided tenements.

Ponti’s Villa Koo is obviously not part of this culture; instead, it is an example of a private residence for Hong Kong elites of the Chinese diaspora. The house seems to have served as a kind of signifying space of non-aligned retreat – both a withdrawal into the hills from the highly public life of the city, and an active political positioning neither in league with the Western imperialism seen as signified by International Style architecture, nor aligned within the Chinese Nationalist-Communist split. When talking to journalists, Koo brought attention to Ponti being Italian when he discussed their collaboration, rather than identifying him with the West; similarly, he aimed to focus foreign attention on the specificity of Hong Kong (Koo 1976). This challenged the Cold War rhetoric and racializing tendencies of the time.

7 | Villa Koo designed by Gio Ponti for Daniel Koo Shing-cheong (1963). Source: Gio Ponti Archives, 266EST03.

The most noticeable characteristic of the Villa Koo design is the almost scaly exterior surface of the ground floor and first floor, covered in white ceramic pebbles [Fig. 7]. Its knobbiness encourages haptic sensibilities, a connection between touch and sight, proximity and distance. Ponti employed these ceramic pebbles variously in different projects. For example, in the House in the Pine Wood (Villa Ercole, Arenzano, Genoa, 1955), he used small pebbles, painted blue, to frame and accent windows (Ponti 1990). In the Hotel Parco dei Principi (Sorrento, 1962), he used them on interior walls in the lobby to create geometric designs in blue and white that combine sweeping curving line with circles, ovals and diamonds (Ponti 1990). The textured white surface of large smooth pebbles at Villa Koo breaks down the solidity of the house softening its relationship with the surrounding wooded environment. It is perhaps due to the building’s contour – a flat roof made to appear to sag with a delicate curve [Fig. 8 to Fig. 11] like a lung exhaling – that, even if markedly dotted with stone pebbles, the walls appear to be a porous, breathing, protective skin, rather than an enclosure to constrain and confine.

Some have identified the late 1960s as the moment when Hong Kong’s now characteristic “bathroom tile” cladding was popularized (Gaskell 2019). Covering interior and exterior surfaces with glass and ceramic mosaic tile protected walls and floors from the impact of the city’s humidity; when affordable products came onto the market from China, tiling was in demand, no longer an expensive import from Italy and Japan. Ponti’s work with pebble cladding is an iteration of what he was doing with the tiles he was designing for interiors (Ponti 1990) and – as will be discussed further in the section on Shui Hing – experiments with light, reflective surfaces, and the formats of facades.

Any position of elevation in the Hong Kong landscape is always a statement and Villa Koo, high in Hong Kong island’s hillscape, takes such a sentinel post [Fig. 8]. The colony legally enforced segregation of its population and the racialization of space through the control of elevated places (Nightingale 2012, 146-147). For example, until 1946, Chinese residence on the island’s highest hill, Victoria Peak, was restricted (ibid). In colonial era Hong Kong, the highest points in the landscape were reserved for British and European colonial subjects, with Chinese and even Eurasian elites occupying middle grounds. Low-income marginalized populations were left to low-lying terrain or rocky elevated areas difficult and dangerous to inhabit (Ibid). The legacy of this spatial order can still be seen replicated in new contexts, though the racializing dynamic has been further complicated by later migrations of wealthy mainland Chinese; nonetheless, both in high-rises and in outlying islands, distance is a privilege except when too inconvenient.

The house that Ponti built for Koo was designed for a sloping plot of land on a hill situated between a taller mount – Mount Nicholson – and a reservoir – Wong Nai Chung Reservoir, one of the oldest surviving waterworks on the island. This positioning between mountain and water – “embraced by hills on three sides” with some “southerly orientation” and “gently flowing water… in front of the site” – appears to combine modernist design and spatial order in the colonial hierarchy, with the principles of Taoist and Hakka geomancy, or fung shui (used in both Cantonese and Mandarin, literally translated as ‘wind, water’) (Ali and Hill 2005, 27-39). It should be said, however, that Ponti’s sensitivity to the landscape in this instance is also similar to that which Fulvio Irace recounts in the Villa Planchart, “a work not made to rest on the hill but that makes the hill visible” (Greco 2008).

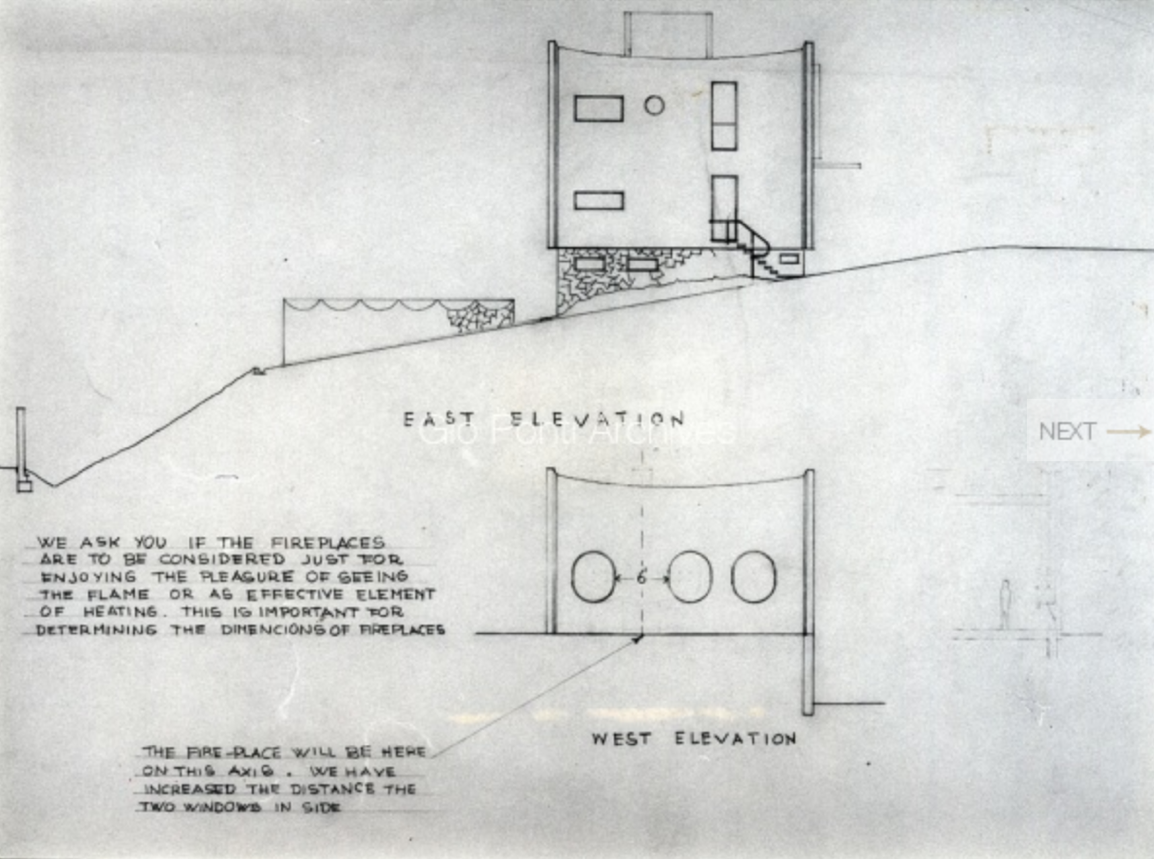

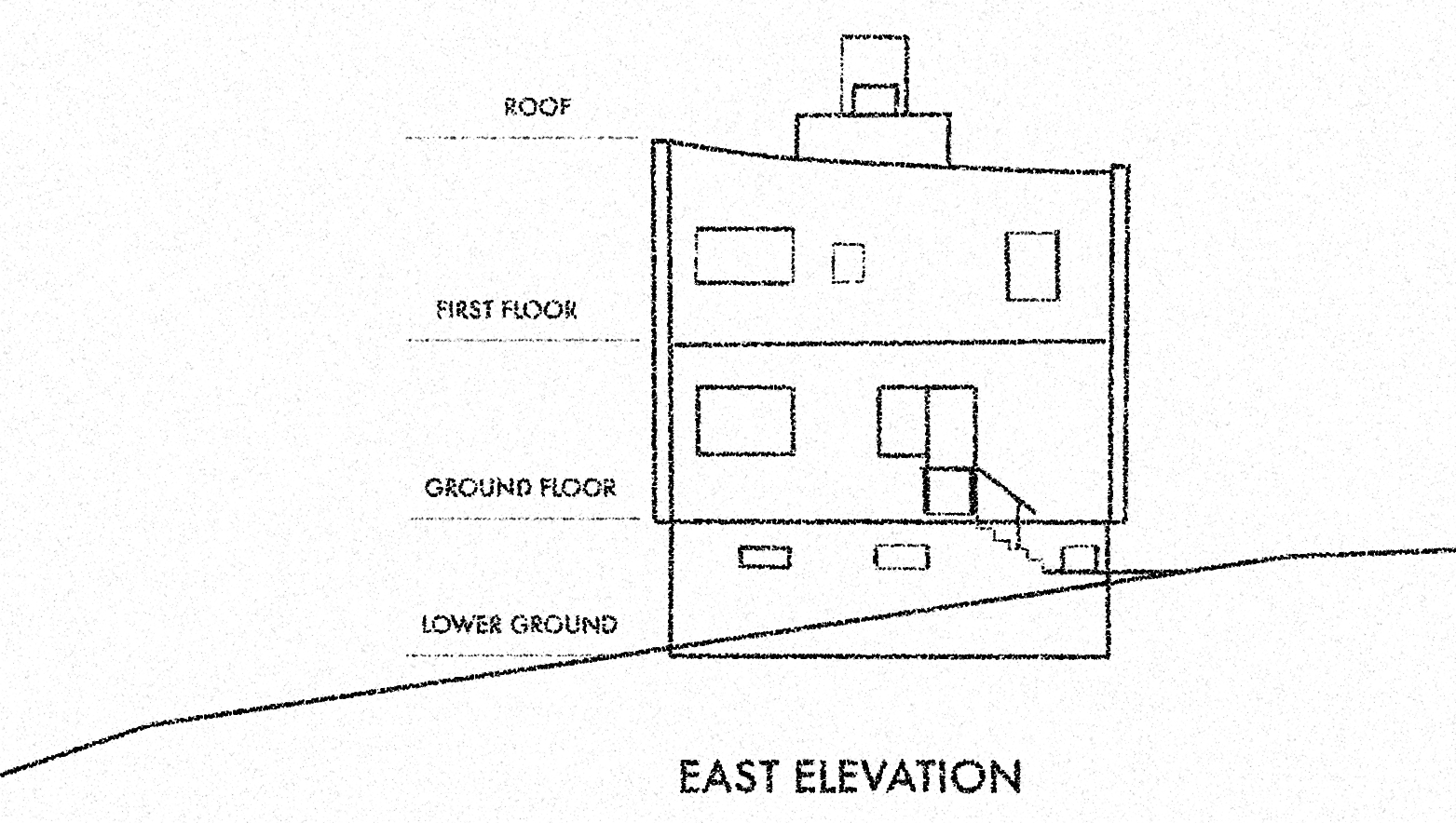

8 | East and west elevation of Villa Koo designed by Gio Ponti for Daniel Koo Shing-cheong (1963). Source: Gio Ponti Archives, 266DIS01.

It was between his theorization of “una casa a pareti apribili” (a house of opening walls) and “la casa adatta” (the apt/adapted house) in 1957 and 1970 respectively (Palandri 2019, 1-13), that Ponti took on the commission for the Villa Koo in Hong Kong’s Tai Tam. For Ponti, the home was conceived in a dialectic between public and private as “shelter from public life” (LaMonaca 1997-1998, 54). Koo’s house is an interesting iteration: a publicly private space – an important private commission purposively hidden from the general public, only shared selectively, but still important to Koo’s public image.

As architect Alessio Palandri has shown in his focused study on Ponti’s houses, in these commissions the architect sought to open domestic space to being something other than a cluster of distinct rooms. As Palandri writes, “for Ponti, in fact, the necessary sense of freedom that has to be perceived in the use of the domestic space can also be achieved with an adjustable and expandable space, to evade that possible feeling of coercion that can be perceived within a limiting rigid structure […]” (Palandri 2019, 13). In 1976, Ponti wrote: “the ideal house is not a constraint” (Ponti quoted in Ibid, 1). Palandri also emphasizes that Ponti’s magazine, “Domus”, encouraged its “readers to transform their home environments to meet their personal requirements” (“Domus” quoted in Ibid, 1). For a house in colonial Hong Kong inhabited by diasporic Chinese, issues of coercion and constraint are especially complex. Ponti, who navigated Italy’s own complicated political issues across the two World Wars (Schnapp 2004, 206), created designs for Hong Kong that show empathy with this complexity.

As Marianne LaMonaca has written in her study of Ponti’s early program for the modern Italian home between 1928 and 1933, late nineteenth century writing about architecture had focused on the home as “the essential monument” of “a democratic society” and, it was in recognition of this, that Ponti started his magazine “Domus”, titled after the Latin word for house (LaMonaca 1997-1998, 53). As evidenced by the Young Plan, democracy in Hong Kong has long been an issue of debate, first under British imperialism, now under centralized Chinese Communist Party control, wary of international interference. Though his designs seem sensitive to this issue, there is little documentary evidence that Ponti reflected on it. In fact, his work in Hong Kong effectively revolved around his personal commissions and, unfortunately, the “Domus” archive suggests, he did little to explore the city, its architects, and architectural history. Hong Kong was only profiled in “Domus” in 1998, a year after the transfer of sovereignty from Britain to China (“Domus” 1998, 38-59); otherwise, the only focused attention on design in the city appeared with Ponti’s own Shui Hing, profiled before and after its construction in 1961 and 1968 [Fig. 9] (“Domus” 1961, 90-91; “Domus” 1968, 56-57), and a short write-up on Hong Kong-born Kwok Hoi Chan’s ‘Pussy Cat’ chair designed for Steiner in Paris in 1970 (“Domus” 1970, 12-13).

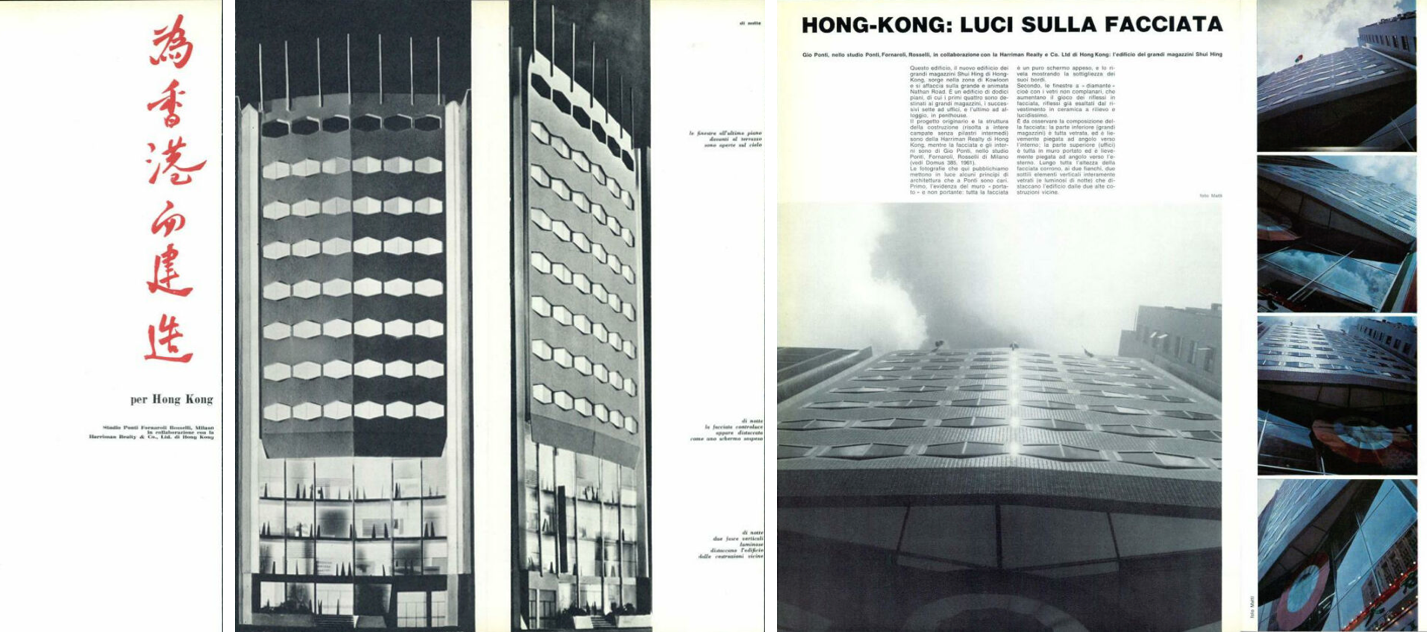

9 | Title pages of Ponti’s two articles for “Domus” on the Shui Hing project in Hong Kong: “Per Hong Kong” (For Hong Kong), 1961 and “Hong-Kong: Luci sulla Facciata” (Hong Kong: Lights on the Façade), 1968. Source: “Domus” Archive.

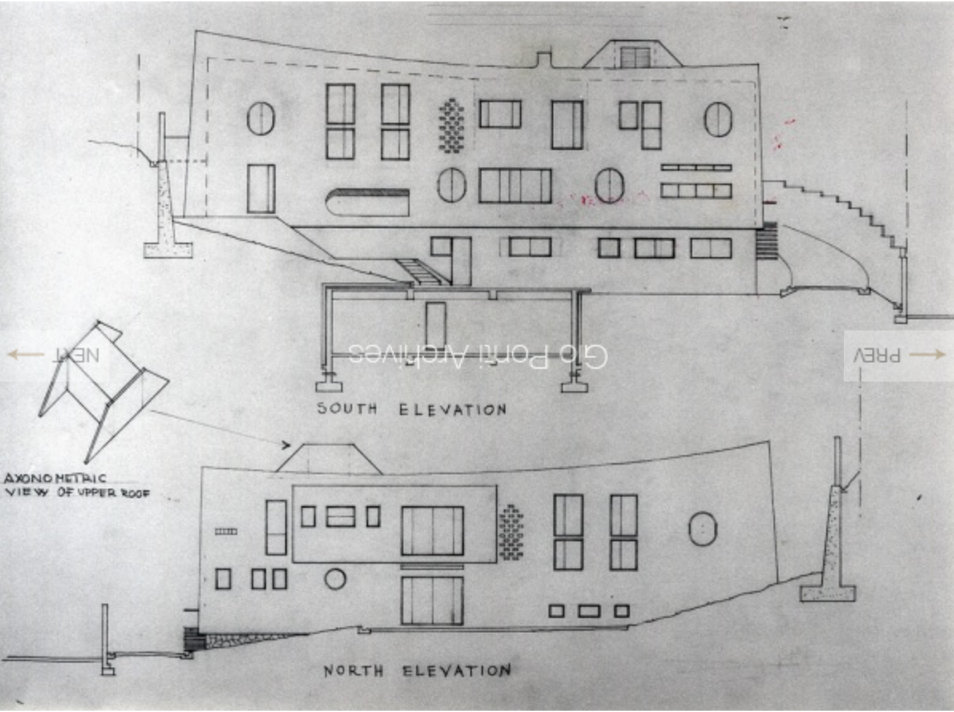

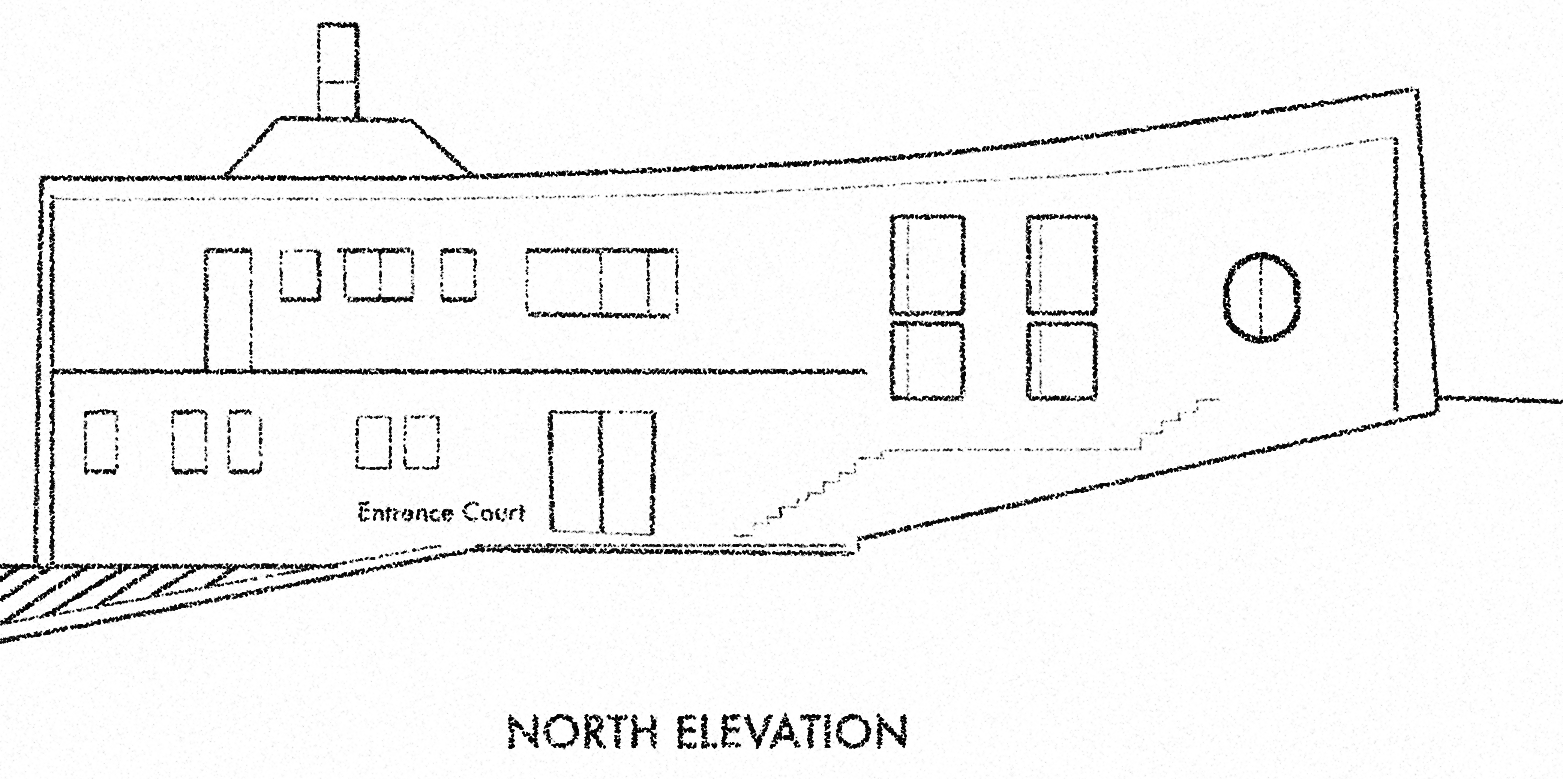

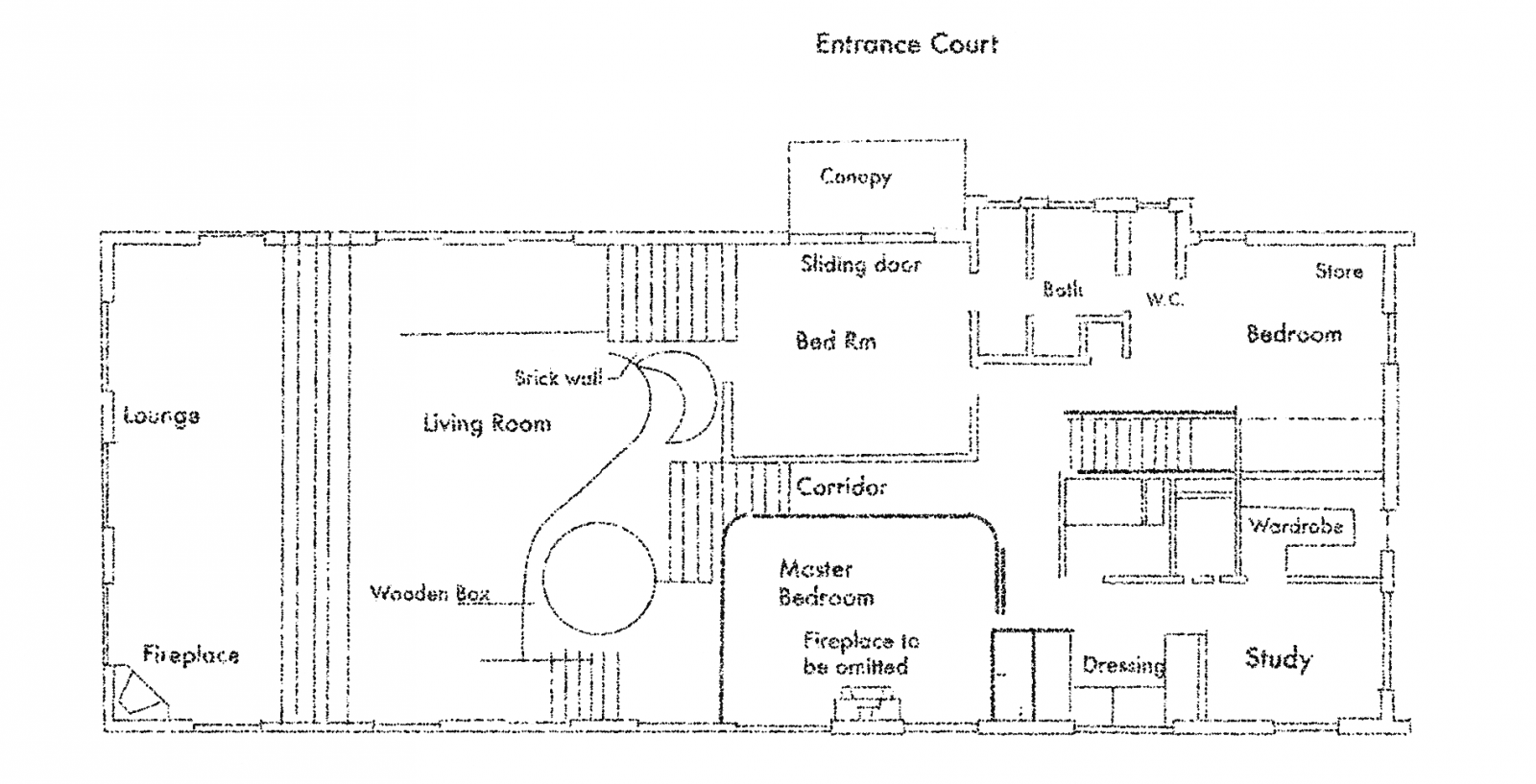

In her own profile of Villa Koo for the Gio Ponti monograph published in 1990, Lisa Ponti, the architect’s daughter, describes the house very briefly from its south and north elevations; no floor plan is discussed, and, in fact, there are no floor plans digitized in the Ponti archive available online. In his writings, Ponti emphasized that his houses were “a game of spaces, surfaces and volumes offered in different ways to those who visit. […] [A] ‘machine’ or, if you will, an abstract sculpture on a massive scale, not to be viewed from outside but to be experienced from within, penetrating it and moving through it” (Ponti 1961). Nonetheless, Lisa Ponti’s brief text focuses on the way the interior impacts experience of the exterior: “both front walls,” the architect’s daughter writes, “are pierced by windows of different forms, at different levels from the floor [Fig. 10]. In the living room, the floor ‘rises’ towards the portholes in the back wall” (Ponti 1990, 217) [Fig. 10].

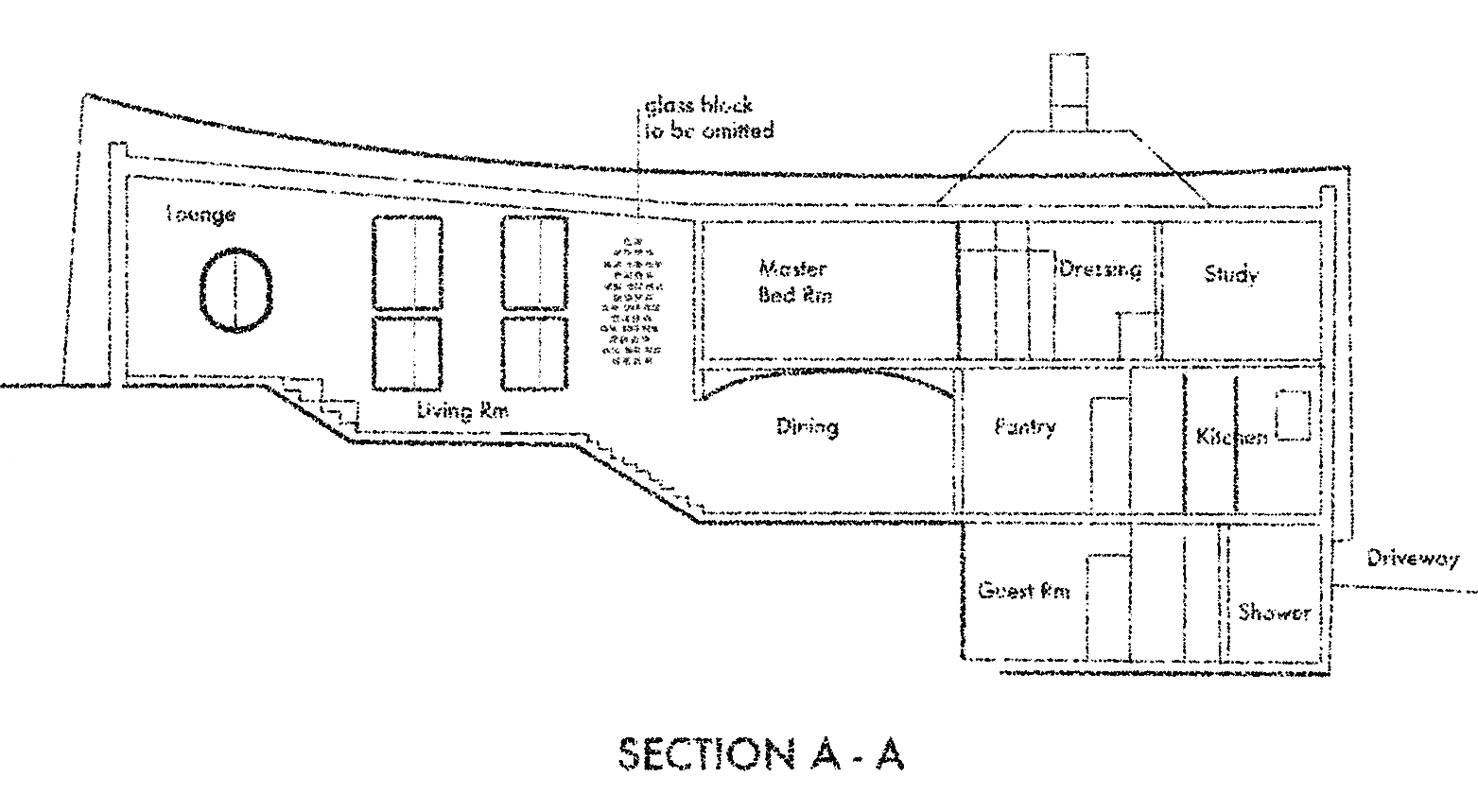

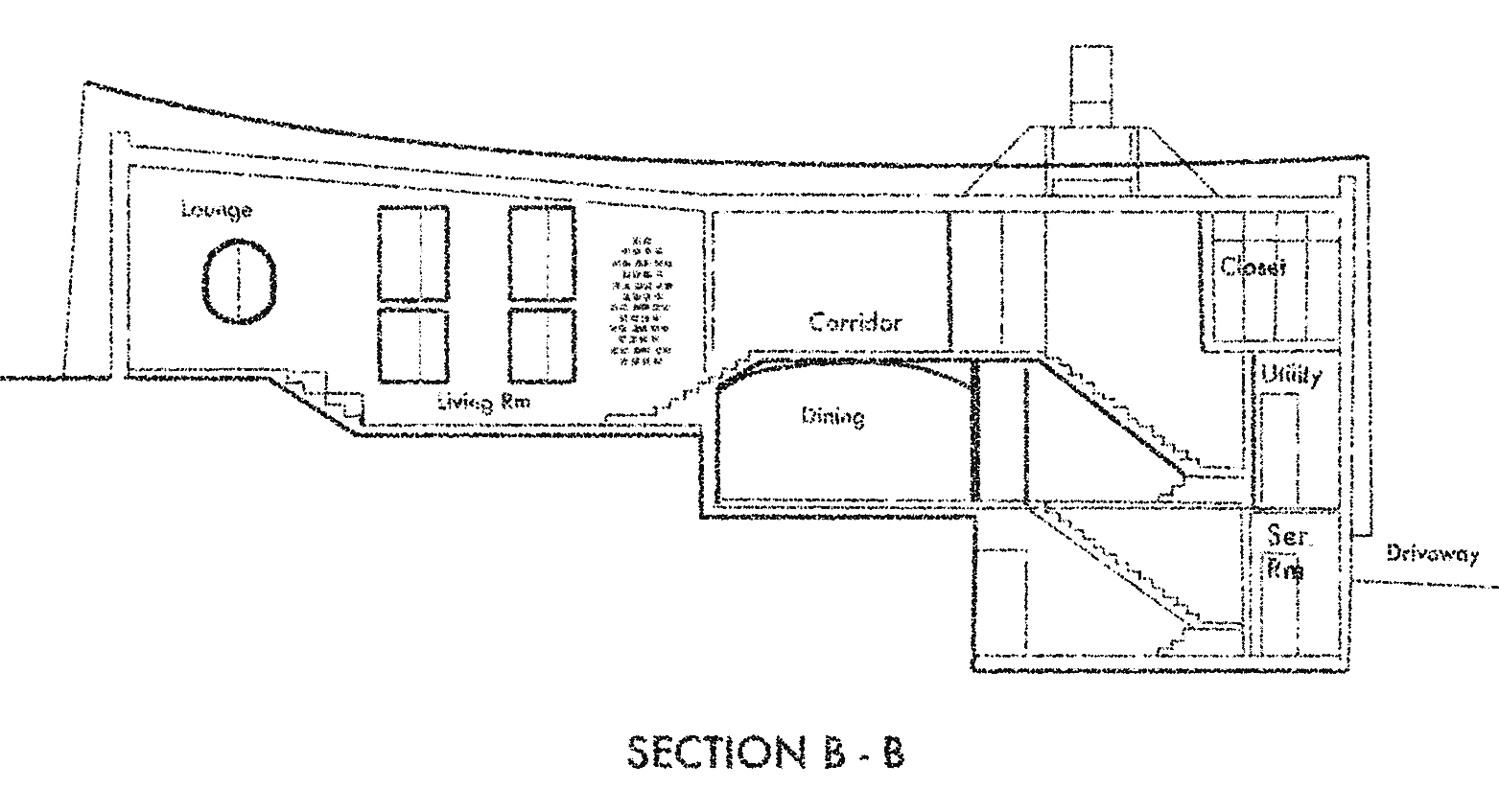

Floor plans of the house submitted to Hong Kong’s Buildings Department between 1970 and 1972 – when some small adjustments were made – reveal more about the experience of the “living room” space described by Lisa Ponti [Fig. 11]. The “living room” is actually a compound open space labeled “lounge,” “living,” “hall” and “dining” [Fig. 11]. Between each of the spaces, sets of stairs make the visitor aware of the rising terrain under foot. To emphasize this experience, the floor rises twice with short sets of steps before meeting the wall of portholes to the west [Fig. 11]. It is indeed the case – as Lisa Ponti notes – that both the north and south elevations show windows of different size and shape [Fig. 10]: rectangular vertical and horizontal windows, narrow horizontal strip windows, and ovoid windows (the “portholes”). From outside, the windows are indicators of the different spaces inside [Fig. 11]: the lounge space is surrounded by the ovoid windows and the living room has pairs of rectangular windows that span floor to ceiling. As photographs of the interiors show, this changes the way light filters into the interior [Fig. 1, 2].

10 | South and north elevation of Villa Koo designed by Gio Ponti for Daniel Koo Shing-cheong (1963). Source: Gio Ponti Archives, nr. 266DIS02.

Glass blocks, later omitted, were originally planned for both the area of the stairs between the living room and the first-floor corridor, and that between the living room and the ground floor hall [Fig. 11, top]. Stairs connect the three floors not only from the west, where the lounge and living spaces are located, but to the east where service areas like utility rooms, closets and storage stand over the driveway [Fig. 11, bottom]. A protective wall in stone on the outside of the house lines the ground floor where the dining room is situated to create the sense of lightness, suspension and emergence that Ponti sought in this period (Ippolito 2009, 52). The dining room looks out onto a garden to the south facing Deep Water Bay Road.

11 | Sections of Villa Koo (top, Section A-A; bottom, Section B-B) designed by Gio Ponti for Daniel Koo Shing-cheong (Architect Gio Ponti, 1963; plans for adjustments, Ping K. Ng, 1972; drawn by K. S. Hon). Digital sketches in Illustrator made from studying the original technical drawings available for public consultation in BRAVO. Sketches by András Blazsek.

The large compound living space [Fig. 11] covers two floors with one set of stairs leading down to the hall and dining room on the ground floor, and another set climbing up to a corridor that opens into bedrooms on the first floor. The corridor on the higher level opens into three bedrooms, one of which has sliding door access to a canopied terrace. The plans indicate that a fireplace originally planned to connect outside to inside in the master bedroom was removed, but there is another hearth in the southern corner of the lounge, and brick walls and teak handrails provide further warmth and texture. On the lower ground, a concave hollow in the false ceiling over the dining room softens cubic edges and corners [Fig. 11]. Ponti is always breaking any sense of confinement or captive enclosure in the house.

As was also the case with Villa Planchart, the location of the house is important to understand in relation to the design. From the west, the house appears to be a single story, with the first floor on ground level [Fig. 8]. From the east, it reveals it has three stories with lower ground, ground, and first floors [Fig. 8]. The three ovoid windows point west up the slope towards Mount Nicholson rather than down in the direction of the reservoir. The reservoir is not visible from the plot of land where the house is located but can be viewed just steps around the bend in Deep Water Bay Road. Just as the floor is made to rise with the terrain under the house, the flat roof is made to appear slightly curved from the west and east, rising from south to north by almost a foot and a half [Fig. 12]. The terrain not only slopes down from north to south, but from west to east, as well [Fig. 12]. Thus, in one direction, Ponti designed the top edges of the surrounding building envelope to make the roof appear to rise opposite the tendency of the terrain, curving up to the south [Fig. 12, top], while the hill climbs to the north; in the other direction, the roof appears to rise with the terrain, curving up east where the hill also ascends [Fig. 12, bottom].

12 | East elevation and (bottom) north elevation showing the curving roof of Villa Koo designed by Gio Ponti for Daniel Koo Shing-cheong (Architect Gio Ponti, 1963; plans for adjustments, Ping K. Ng, 1972; drawn by K. S. Hon). Digital sketches in Illustrator made from studying the original technical drawings available for public consultation in BRAVO. Sketches by András Blazsek.

The entrance court to the house is from the north [Fig. 12, bottom and Fig. 13, bottom]. In other words, the house does not face Deep Water Bay Road to the south, though its dining room looks out in that direction and visitors must approach that way. The deliberately orchestrated indirect entry requires going up a curving driveway and around to the opposite side. This indirect access continues upon entry into the house: the entrance to the house does not open immediately into the living room but to a hall where the visitor has to turn right and climb a short set of steps before entering the living space [Fig. 13, bottom].

13 | Plans of ground floor and first floor of Villa Koo designed by Gio Ponti for Daniel Koo Shing-cheong (Architect Gio Ponti, 1963; plans for adjustments, Ping K. Ng, 1972; drawn by K.S. Hon). Digital sketches in Illustrator made from studying the original technical drawings available for public consultation in BRAVO. Sketches by András Blazsek.

Though there is no evidence to suggest that Ponti was influenced by the study of architectural space in Chinese thought, it should be noted that this play with indirect access and the dialectic between shaping and filling of space resonates with practices in Ancient Chinese garden design and the disposition of courtyard houses (Liu 2016, 195-211).

The Villa Koo in Tai Tam is not discussed in Palandri’s study of the evolution of the idea of domestic space in Ponti’s work, but the study mentions “Casa Koo” (Koo House, 1969), another commission for Koo but in San Francisco, that Palandri asserts was important to the architect’s experiments, conceptualizing the dwelling as “una piccola città” (a little city) (Palandri 2019, 11) by means of a colorful set of drawings. The project theorizes the home-as-city in a “circular body” that resembles Hakka roundhouses in southwestern Fujian and northern Guangdong (Constable 1994, 12), though any connection is only speculative. The sustained relationship with Koo and the playful nature of these drawings suggests that Ponti continued reflecting on his Hong Kong experience as his practice migrated into other contexts.

The Client: The Political Unconscious in Designs for Daniel Koo

Over the past twenty years, architecture as a design process of cooperation, confrontation and collaboration, rather than of the architect’s absolute authorship has been the focus of a number of histories (Donchin 2013; Ferguson 2000), including a volume on Ponti’s work on three hotels for entrepreneur Roberto Fernandes in Naples, Sorrento and Rome (Mautone 2009). In 2005 – evidently cognizant of this shift and the growing influence of Chinese commissions – Lisa Ponti attempted to bring more attention to the specific architect-client relationship between her father and Koo with an article in the magazine “Abitare” (Ponti 2005, 164-167). Along with cinema magnate Run Run Shaw and the owner of Tung Tai Trading Company, Leo Lee Tung-hoi, Koo had been awarded the Order of merit “Cavaliere” (Knight) by the Italian President and was proud of the honor (“Italian Award for Local Resident” 1966, 5). Lisa Ponti refers to him as the “much-loved Chinese client”, praise which simplifies Koo’s identity rather than celebrating diasporic hybridity, but that indicates the relationship was important to Ponti.

Unfortunately, Lisa Ponti’s article only symbolically points to Koo’s commissions with the basics about the projects that Ponti worked on for him. Finding aids available online for the Gio Ponti Archive indicate there is conserved correspondence between the two men from 1965 to 1978; however, these materials could not be consulted from Hong Kong during Covid-19 closures. Without access to this correspondence, the best way to begin exploring the relationship between client and architect is through Ponti’s own “Domus”, founded in 1928, and Hong Kong’s English-language newspaper “The South China Morning Post” (Scmp) founded in 1903.

Ponti arrived in Hong Kong preceded by the fame of the Pirelli Tower (Milan, 1957) and his participation in the design of the new capital of Pakistan, Islamabad, directed by Greek architect and planner Constantinos A. Doxiadis (1959) (“Italian Architect Designs H.K. Store” 1962, 7). One has to read between the lines of SCMP reporting on Ponti’s Hong Kong project to get what appears to have been its intended message: for those who still cared about the failed Young Plan for electoral reform in Hong Kong – officially abandoned in 1952 after the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949 – the reference to the partition that created Pakistan and granted independence to India (1947) was evocative. The goal was not so much to foment new hopes for Hong Kong to become a self-governing state but to inspire other kinds of reform that might be made possible through commitment to trade relationships. Afterall, the new Italian constitution drafted after the defeat of fascism in 1948 had involved complex negotiations of power between democratic socialists, Christian democrats, communists and liberal democrats in their alignment as anti-fascists, and Italy was in an economic boom. Perhaps the same could be accomplished with communist China in capitalist Hong Kong.

In 1962, a year after the announcement of Ponti’s collaboration with Koo, a five-member delegation set out from Hong Kong to visit Milan and Rome to promote Hong Kong products, specifically “transistor radios and general made-up garments” (“Opportunities for Colony’s Products In Italy” 1962, 18). The new efforts also worked to bring different kinds of Italian products to Hong Kong. Italians hoped Hong Kong would participate in the 40th edition of the Fiera di Milano in 1962 and, among Koo’s reported aims, was the desire to make Italians understand that Hong Kong goods did not come from China or Japan but were locally manufactured. Koo also emphasized that the trade relationship between Italy and Hong Kong was unbalanced, with Hong Kong bringing in three or four times what Italy bought from the colony. Between 1969 and 1971, these efforts saw trade grow by 52% (Ramanath 1971, 8). In 1971, Hong Kong was importing “Italian cars, typewriters, consumer goods, textile goods, footwear, refrigerator equipment and pharmaceutical goods,” while Italy was importing Hong Kong’s “plastic toys, cotton fabrics, transistor radios and clothing materials” (Ibid).

Between the 1970s and the 1990s, shifts in the Hong Kong retail industry saw operations move from a localized focus to international networks. Koo had in part facilitated this trend, but he had aimed to bring international brands into the city via a Hong Kong local department store, and with attention to specific countries rather than a multi-national sweep. In the 1980s, his activities were challenged by Japanese and Anglo-American stores that expanded their business to Hong Kong and intensified competition. In this period, Koo diversified Shui Hing’s activities. Along with its operation of department stores, supermarkets and specialty stores like his brother Raymond’s Promotors – manufacturers of television receivers from 1967 until 1986 (Lo 2017) – Shui Hing also invested in property for rental, investment and trading, moving into real estate speculation (“Shui Hing Co Ltd.” 1993, 79). In November 1997, Koo sold his 71.3 percent stake in Shui Hing for $934 million and the company was renamed Easy Concepts by Easyknit International, another company primarily engaged in property development, securities investment and loan financing (Chan 1997).

In 1993, Koo’s penthouse office at Shui Hing was the establishing location for an article in the Asian Wall Street Journal about Sino-British debates over pre-Handover electoral reform in Hong Kong (Wong 1993, 1). The then sixty-nine-year-old department store magnate was made to figure as a representative of the city’s concerned business interests this time, performing his worry about controversy over then Hong Kong Governor Chris Patten’s support for efforts to create more electoral accountability in the colonial legislature. The British had developed the Hong Kong legislature for little executive control, and, in the lead up to the 1997 transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong from Britain to China, nothing about this aspect of its legislative reach was questioned; however, there were efforts reminiscent of the Young Plan to include more occasions for decisions to be made by popular vote. The new Governor – who took power in 1992 – was seeking ways to secure the promise of Article 5 of the Basic Law, drafted as part of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984, asserting that, with the Handover, “[t]he socialist system and policies shall not be practised in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, and the previous capitalist system and way of life shall remain unchanged for 50 years” (LCQ6 2016).

Stakeholders did not necessarily agree on what was the best way to protect “the previous capitalist system and way of life,” and many concerned with electoral reform did not have the preservation of capitalism as their main aim, but were instead concerned with beginning a conversation about facilitating Hong Kong in its struggle to self-transform as part of the decolonialization process. Twenty-six years later (in August 2019) anti-extradition law amendment bill protests occupied the streets: they were concerned as well with changes that threatened Article 5, but were similarly involving many people more interested in actively shaping their city than protecting capitalism and its privileges. Riot police charged demonstrators under clouds of tear gas that billowed down the road in front of the Tsim Sha Tsui police station (Tong 2019; “As It Happenned” 2019). In October, a singalong protest was staged across the street from Koo’s old office, an expression of solidarity between Hongkongers and the ethnic minorities who live, frequent and run businesses in the iconic Chungking Mansion. The singalong took place after Hong Kong Police fired the water cannon they were using to disperse protesters at the Kowloon mosque, staining its entrance with the blue dye that is added to the water to mark those targeted by the cannons for later arrest.

In the 1993 Asian Wall Street Journal article that used Koo’s office in Shui Hing as its opening location, the reporter also writes about a photograph of Koo at a gathering of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Committee (Cppcc) displayed for visitors (Wong 1993, 1). The gathering was a visit with Chinese leader Deng Xiao Ping, respected orchestrator of the One Country Two Systems solution to China’s so-called “Hong Kong and Taiwan problems” (Deng 1984). The Cppcc has its origins in Chinese Nationalist and Communist attempts to forge a united front against Imperial Japan (Forster 1998, 69-70). In 1949, it was the political body that declared the foundation of the People’s Republic of China under Communist Party dominance over the Nationalists. Transformed into a forum to encourage engagement with both non-aligned and non-communist democratic positions, it was dismantled during the Cultural Revolution, then revived in 1978 under Deng when the Chinese political leader returned to power after a period of alienation and devised One Country Two Systems. “Let us stop this destructive debate over democracy before it gets too late,” Koo urged in response to the reporter pressing him about his membership in the Cppcc (Wong 1993, 1). Ironically, for assumptions about lack of transparency in Cppcc politics, it is in a list of nominations for the committee circulating online that Villa Koo’s address as Koo’s principal residence in Hong Kong seems to have been released to the public for the first time.

Shui Hing: The Building Which Changes Colour According to the Sun’s Rays

In his seminal book on architecture in Hong Kong, Charlie Xue writes of Landmark (1982) and Pacific Place (1988) as “the first generation of shopping malls in Hong Kong” (Xue 2016, 130-131), focusing on the atrium plan that is now prevalent in most designs. As a Chinese family-run department store built two decades prior, rather than a colonial property developer’s shopping mall, Shui Hing is perhaps missing in this history of mall architecture because it precedes it as an associated antecedent rather than direct relative. Cecilia Chu’s writing about New Town Plaza (1984) in Sha Tin [Fig. 14, left] has recently expanded Xue’s Hong Kong Island centered history of the shopping mall with an important example from New Territories. New Town Plaza was an iconic shopping centre of the atrium plan design that became especially significant in recent years, according to Chu, because it experienced “a series of ‘bottom up’ initiatives to revive the sense of place” which nearby residents felt it had lost after renovations raised rents forcing the closure of long-time shops (Chu 2016, 83-84). In her article, Chu explores civil society efforts and nostalgia in Hong Kong in the unexpected context of shopping mall culture.

14 | New Town Plaza in Sha Tin (drawing from 1984); Ocean Terminal in Tsim Sha Tsui (1970); and Shui Hing (ca. 1970s). Sources: 新沙田月刊 as reprinted in Chu 2016, South China Morning Post and Hong Kong Heritage Project Archive.

To give a sense of how architecture, shopping, civil society and dissent combined in Kowloon’s Tsim Sha Tsui, Eunice Seng writes about Chungking Mansions becoming a “base for ‘missile’ launches” (Seng 2020, 108) against protests on the shopping thoroughfare Nathan Road targeting the colonial administration in 1966 (Ibid). Similarly, Tai-Lok Lui has written about the opening of Ocean Terminal [Fig. 14, middle] in Tsim Sha Tsui that same year – just three years after Shui Hing was built – as a significant marker of a “new generation of local consumers”: “young people […] restless and eager to look for new symbols” for whom “consumption […] and presenting […] as different from their parents, became something symbolically charged” (Lui 2001, 38). Whereas Shui-Hing was still tourist shopping [Fig. 14, right] (The Bulletin 1984, 16) – high consumption for affluent locals and foreign visitors – Ocean Terminal (now part of Harbour City) served the multitude, even young intellectuals who regularly met at the famed Café do Brasil, recently the subject of reflections by artists and curators at an important exhibition at Hong Kong’s contemporary art centre, Para Site, in 2019.

While discontented Hong Kong youth transformed Ocean Terminal into an unusual mix of consumption, fantasy and intellectual activity, Shui Hing carved out a space for itself amid the three major department store markets. The Chinese stores like Wing On and Sincere sold merchandise from Europe to middle-to-high income groups; Anglo-American retailers like Lane Crawford and the Duty Free Shoppers Group marketed to tourists and middle-to-high income groups; the Japanese department stores like Daimaru targeted the Japanese in Hong Kong with merchandise from Japan and Europe (Ho 2002, 57). In the Italian relationship he was looking to establish for Shui Hing’s other trade activities via the department store in Tsim Sha Tsui, Koo was perhaps looking to set Shui Hing up to profit when Italy would eventually come around to buying the number of refrigerators and televisions that the six other major European countries had started to consume at higher numbers (Scarpellini 2011, 131).

Recounting the history of Shui Hing to the “South China Morning Post” on the occasion of the company’s 50th anniversary, Koo emphasized entrepreneurialism and innovation (Koo 1976, 13). As he told it, the business started as a convenience shop selling grocery products at a location between Queens Road East and Le Chit Street. It expanded and contracted over the decades, growing between the 1930s and 1940s when it moved to Des Voeux Road in Central. During World War II it shrank, changing leadership in 1946 when Koo Shui Ting, the family patriarch, died. Shui Hing found new prosperity under Daniel Koo’s leadership. The story is a typical Hong Kong one: a tale of making something from little-to-nothing, and of a son honoring his father.

The ‘firsts’ that Koo recounts are numerous and indicative of his values. Shui Hing was the first to “branch out” to Causeway Bay in Hong Kong island, and to Mongkok and Tsim Sha Tsui in Kowloon, now famous shopping districts (Ibid). It was the first to use the so-called “magic door” by Stanley Works, an automatic door activated by photo-electric cells that opens on a hydraulic operator. It was the first to install American General Electric closed-circuit televisions for surveillance over the store, and the first to “stage a trade promotion of a country’s product,” starting with Italy, then running French, Canadian, American and Australian promotions (Ibid). It was also the first to have a store “without any columns and with split levels,” as Koo boasts, “even our Japanese competitors came down to see this major store of ours” (Ibid).

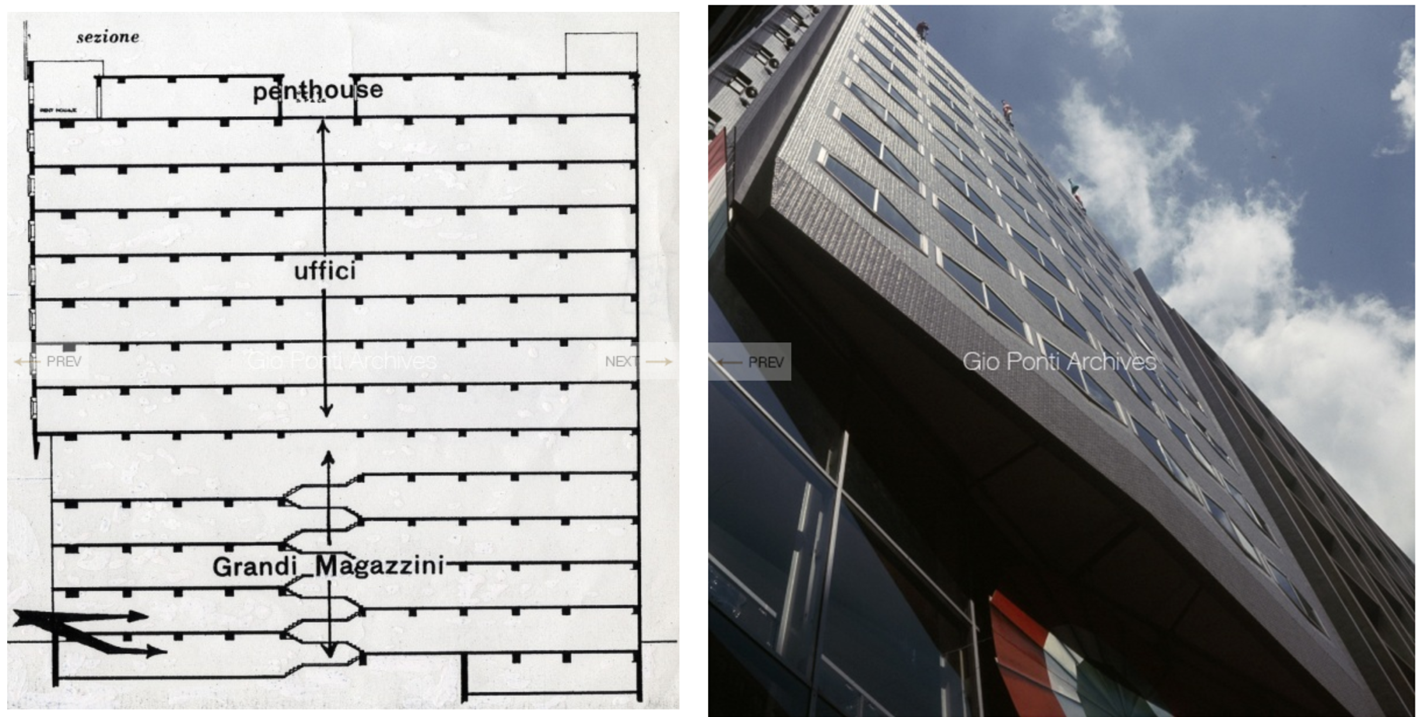

The design of Shui Hing was a collaboration between Studio Ponti Fornaroli Roselli and a local architect from the Harriman Realty Company, F. de P. Baptista along with local engineer, D.C. Ling (The Hong Kong and Far East Builder 1963, 114). In fact, Hong Kong’s The Hong Kong and Far East Builder announced the building’s arrival with an article title that emphasized this collaboration rather than Ponti’s absolute creative control: “Two Architects Combine on Italian-Style Kowloon Shop & Offices” (Ibid). It was Baptista that designed the building’s open plan while Ponti and his studio were responsible for the façade and interiors.

15 | Schematic plan of Gio Ponti’s Shui Hing project; building designed by F. de P. Baptista (1963, Tsim Sha Tsui); hanging façade designed by Gio Ponti. Source: Gio Ponti Archive, nr. 263DIS08, 263est9.

The “South China Morning Post” excitedly declared that the new façade design Ponti planned for Shui Hing was “revolutionary”: it “would seem to float in the air” [Fig. 15, right] (“Italian Architect Designs H.K. Store” 1962, 7). Diamond-shape ceramic tiles imported from Italy would reflect sunlight and “glitter” (Ibid). Baptista’s plan freeing the construction from internal pillars for structural support, created large open spaces for merchandise and for Ponti’s interior designs: “the closest span would be 60 feet wide,” the report announced [Fig. 15, left] (Ibid). Split level floors on the first five stories of the building would allow customers to “observe merchandise in three different floors at one time” (The Hong Kong and Far East Builder 1963, 115). The same experimentation with surface texture, with cladding, and with the dialectic between shaping and filling space – gently choreographing, but not coercing bodies to circulate through it – is repeated from the design of the Tai Tam house. There is also a similar focus on the experience of approach to the building and haptic qualities of vision with focus on effects like glittering and affects like the sensation of lightness and levitation.

16 | Interior design of Gio Ponti’s Shui Hing project (1963, Tsim Sha Tsui) showing effect of the tapering ‘V’ shape beams with the lighting troughs marking the lowest point. Source: The Hong Kong and Far East Builder; present day interiors of Shui Hing (now Prestige Tower) with ‘v’ shaped structural beams in place but lighting troughs removed for track lighting and chandeliers. Source: Emily Verla Bovino.

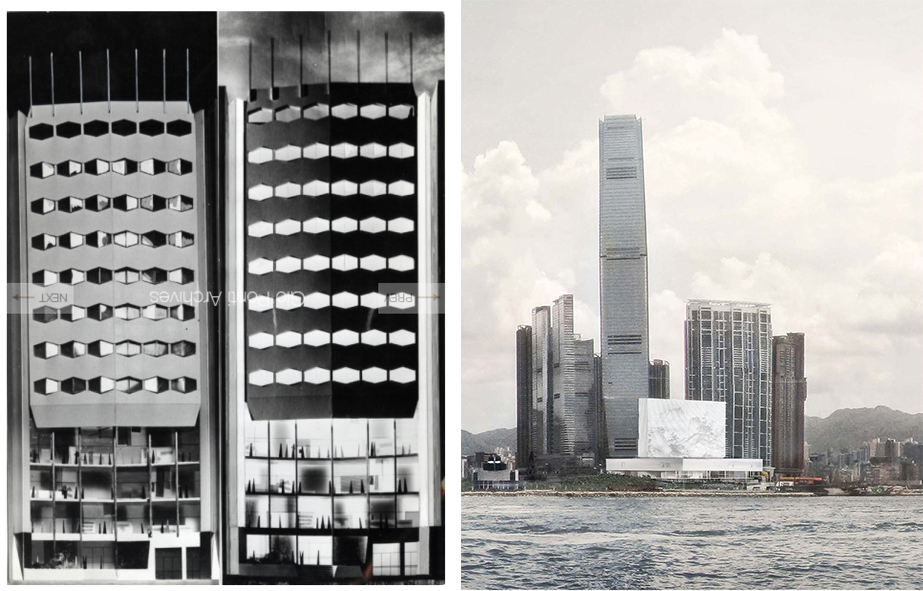

In “Domus”, Shui Hing was presented as a manifesto of sorts, designed according to principles central to Ponti’s approach [Fig. 9] (“Domus” 1961). First, the façade was a “puro schermo appeso” (a pure hanging screen), a hanging wall rather than supporting wall (Ibid). This performative wall, actively exhibiting its characteristics, was supported in the act by Ponti’s lighting design: two strips of light that travelled up each side of the building in the gaps between its façade and those of its adjacent neighbors. Second, the hexagonal windows in non-coplanar glass when looked at from below, also appeared to float, not completely flush with the façade, and the surface of ceramic tiles reflect the refracted light from the windows [Fig. 15, right] (Ibid). Third, the façade itself was also “made up of… planes set at a slight angle”: the angled planes of the first glass-curtained floors of the façade point inwards, while the tiled upper eight floors of the hanging wall façade point outward (Ibid).

17 | Gio Ponti’s Shui Hing project (1963, Tsim Sha Tsui). Source: Gio Ponti Archive, nr. 263EST06; Adolf Loos’s Looshaus (1911, Vienna). Source: Wikipedia.

There is more than just a superficial resemblance between Ponti’s design and Adolf Loos’s iconic Michaelerplatz building (1911, more commonly called the Looshaus) in Vienna [Fig. 17, right]. Loos created the plan for a multi-storied structure with the men’s clothing shops of the Goldman & Salatsch firm on lower levels and four floors of apartments above. The design was made clearly legible by the use of materials: the sensual marble revetment of the monumental commercial area, with its imposing entrance, seduced and dominated the visitor with the combined image of liquidity in marble vein and weightiness of tall bottom-heavy pillars. Inside, the impact continued with surfaces of precious wood, lush carpet, colored marble and plate glass reflecting all the surrounding textures to present goods to an enrapt sensorium (Long 2011; Coleman 2020, 43-44; Klinger 2008, 11).

In Ponti’s Amate l’Architettura (In Praise of Architecture, 1960), he writes about what he “learned from Loos” who, as he specifies, “I knew personally” (Ponti 1960, 127; my translation). In the section of the book about the obelisk, Ponti writes, “[a] foot and a leg of a chair and of any piece of furniture – [Loos] told me – have to always be a bit ‘too thin’, a spire always a bit ‘too tall’, a bridge a bit ‘too taut’ […]: this is the lesson of the obelisk” (Ibid). As Ponti writes, the obelisk represents a “an impossible balance that succeeds: the exactness of an excess” (Ibid). The design of the floating façade, like Loos’s own imposing structure on an ethereal base of veined marble, recalls such an “impossible balance” (Ibid).

In The Hong Kong and Far East Builder article on Shui Hing, emphasis is not only on the façade as it is in Ponti’s Domus, but on the economic benefits of the split level floor layout and the absence of internal columns (The Hong Kong and Far East Builder 1963, 114-116). In the first four stories of the building, the split levels create a total of eight floors. “From all positions on the staircase,” the report reads, “it is possible to see no less than three shopping levels” (Ibid). The landings provide for easy access with no more than seven steps in any one flight of stairs. The overhead lighting troughs designed in a ‘V’ shape were made possible by special structural designs of supporting beams aimed to avoid the need for heavy false ceilings. All of this, according to the article, is value added, or as the quoted theory states: “the goods displayed, the goods half sold” (Ibid). It is this open, light, and split-level design (no longer extant because subdivided) reinterpreted in the context of Ponti’s house for Koo, that complicates the separation between public and private in the Tai Tam Villa. At Villa Koo, the house is a strange “shelter from public life” – as Ponti theorized his conception of domestic space – that would carry the body’s memory of public life at Shui Hing with it in its interior spaces. Thus, it could be said, Koo was never quite sheltered from public life.

Indeed, the model of the Hong Kong family business makes the “family as a unit of production” explicit (Chiu 1998, 18). Daniel Koo always had Shui Hing with him – in him – when he went home at night. This was not – as scholars Heung-Wah Wong and Karin Ling-fung Chau have written in their study of the Chinese family business in Hong Kong – something natural to families in Hong Kong; rather, as this essay has also shown, it was the result of colonial “politicking” that actively sought, “the transformation of the so-called ‘refugee mentality’ of the Hong Kong people to the ‘market mentality’ characterized by the depoliticized, denationalized and de-territorialized-cum-consumption oriented life-style around which the Hong Kong identity was formed” (Wong and Chau 2019, 32). Ponti’s two commissioned designs reflect this lived reality of depoliticized, family business-based, interiority.

In May 2005, “Abitare” dedicated an entire issue to Hong Kong. For Lisa Ponti’s piece on Daniel Koo, “the much-loved Chinese client,” architect and architectural historian Fulvio Irace travelled to Hong Kong to photograph Shui Hing (Ponti 2005, 164-167). In Irace’s photographs, the glittering ceramic tile façade designed by Ponti as an immense non-structural wall – a hanging screen for Baptista’s building – is dulled. A large neon sign advertising “shoestring travel – via tour ticketing” to Chinese customers, eight years after the Handover, competes for the camera’s attention. The allure of the curtain wall glass spectacle of the lower three floors of display space is denied, covered by a massive billboard. Nonetheless, in her article, Lisa Ponti claims to see in Irace’s pictures hints of what she had captured in her own more dramatic black-and-white images almost forty years earlier for “Domus”: light reflecting off the horizontal glass-crystal panels and diamond-shaped windows. Hong Kong was indeed the perfect city for Ponti to experiment “playing with surfaces,” his focus in the 1960s (Ponti 1990, 207). It was ideal for his interest in what he called “nighttime design” and “self-lighting,” the quality of light and luminosity in architectural and interior design.

18 | Maquette of Gio Ponti’s Shui Hing project; building designed by F. de P. Baptista (1963, Tsim Sha Tsui). Source: Gio Ponti Archive, nr. 263DIS02; Simulation of M+ Museum of Visual Culture by Herzog & de Meuron. Source: Herzog & de Meuron.

In September 2020, as Hong Kong is emerging from its second wave of Covid-19 and from the passage of the National Security Law by Beijing on its behalf, the M+ Museum of Visual Culture in West Kowloon is testing its far more monumental façade-as-screen, the LED lighting display system in Herzog & de Meuron’s glass and ceramic louvred façade of the M+ building [Fig. 15]. This 65-meter high and 110-meter long façade-as-screen has been illuminated with pink, green and yellow fields of color in preparation for the moving images it will beam across the harbor after it opens. Hong Kong is caught in a dialectic of wrenching disappearances and ever-more sudden appearances that not only constantly change its landscape but the conditions for life of the bodies that inhabit it. And yet, it is consistently resilient, actively responsive.

Ponti explained the difficulty of the feat: “each space opens on many sides to other spaces, leading to a series of changing architectural events, composed and integrated with one another, with crossed and crossing views, transverses, sequences, from top to bottom and vice versa; with level changes and transparencies, composing planes and spaces in a game with no interruptions, in which new perspectives always appear and are framed as the visitor moves through it” (Ponti 1961). The passage reads like the architectural version of the “sensuous” cinematography and editing in Chungking Express, as described by film studies scholar Sean Redmond: “jump-cuts, elliptical and ‘stretch printing’ editing techniques confuse the relationship between time and space and symbolically problematize character relationships, so that, for example, at one moment, in one shot, the foreground of an event can happen in slow-motion while the background can happen in quick time […] two different and yet simultaneous realities” (Redmond 2004, 8).

Critic Germano Celant, who just passed away this year, wrote the foreword to the seminal Ponti monograph, The Complete Work (1990), titling it “the substantiality of the impalpable” (Ponti 1990). The title is also perfect for the general state of current affairs in Hong Kong, as is Celant’s characterization of Ponti’s life work as “an effort to get rid of any hint of linear development or the monolithic” (Ibid). Hong Kong art and architectural history also do as much, presenting a challenge to any force of coercive authority that aim to define them, any gestures of enclosure that seek to constrain them. Defiant, resistant, resilient: Hong Kong endures appearance and disappearance in its own substantiality of the impalpable.

Epilogue: What Art Knows - Rediscovering Gio Ponti in Hong Kong with artist LeeLee Chan

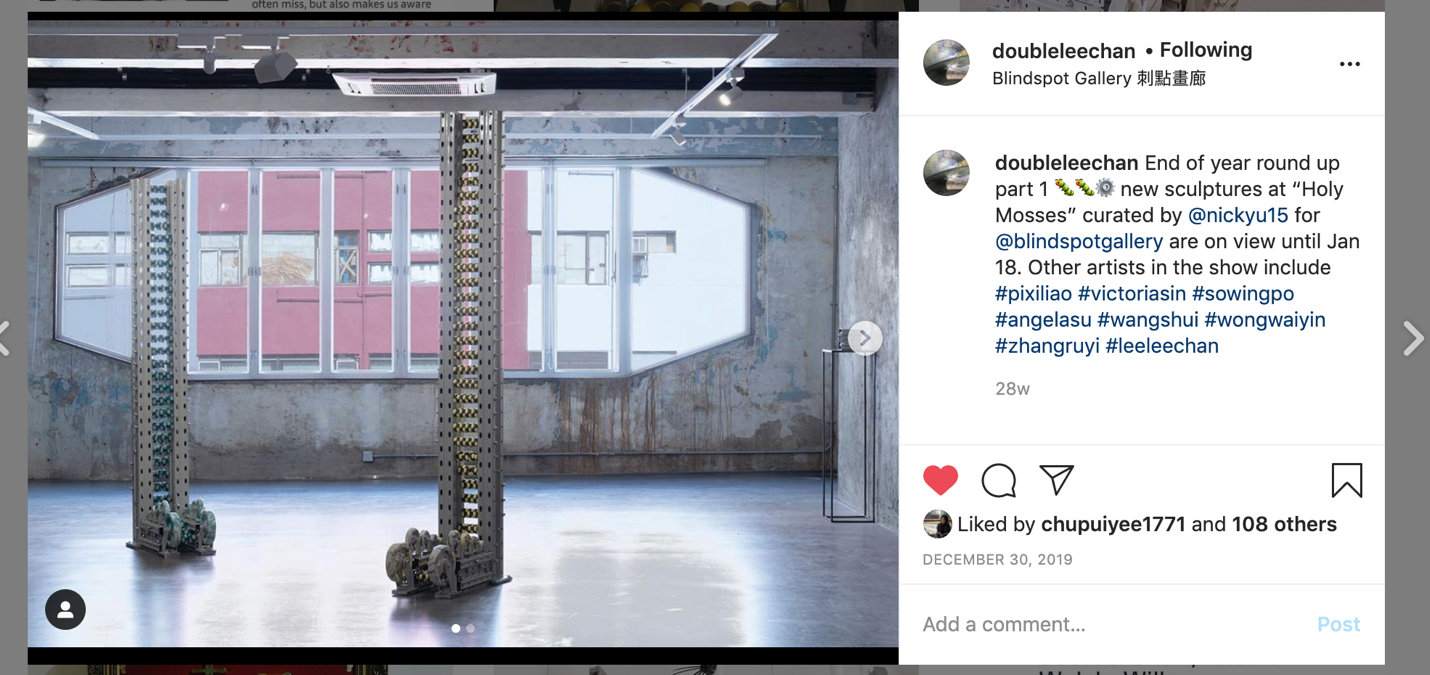

Transit on ferries and the underground was always in my dreams after my family moved back to New York from Hong Kong in the early 1990s. It was, therefore, predictable that my accidental rediscovery of Gio Ponti’s Hong Kong projects for Daniel Koo in 2020, would start while scrolling through Instagram on Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway (MTR). The sudden recall came to me through a complex series of associations between buildings of Ponti’s that I had taught in my architectural history classes, exhibitions I had recently seen in Hong Kong, and images posted by friends on the popular social media platform. That day, in mid-June, amid an easing of Covid-19 social distancing restrictions, I was sailing virtually through waves of images in an effort to distract myself from reading more updates on the coronavirus and Hong Kong’s political situation, when I stopped to linger on a post by sculptor LeeLee Chan.

I first saw Chan’s work at curator Ingrid Pui Yee Chu’s show The Preservationists (2018) at Duddell’s, a two-floor space in Hong Kong’s Central district that hosts both dim-sum dining and exhibitions. Later, I had the occasion to write briefly about one of her sculptures in a review of curator Nick Yu’s show Holy Mosses (2019) at Blindspot Gallery in Wong Chuk Hang. Viewing Chan’s Receptor (caterpillar-yellow, 2019) in the gentrifying industrial area of Hong Kong’s Southern District [Fig. 19, top], made the neighborhood’s state of speculative flux under the construction of an immense new shopping mall feel natural. The feeling broke with any tendency to split nature and culture, the ancient and the contemporary. Wong Chuk Hang is actually one of the longest inhabited areas of Hong Kong, though it is not usually appreciated for this history. Chan’s work silently theorized a materials-based philosophy of what aesthetics calls plastic nature, an animate inanimacy and inanimate animacy that changes the body’s relationship to the space around it.

19 | Leelee Chan’s Receptor (caterpillar-yellow, 2020) and Receptor (willow-green, 2020) on view at Blindspot Gallery in the Po Chai Industrial Building; Leelee Chan’s Celadon Weaver (2020) on view at the exhibition Up Close – Hollywood Road (2020). Source: Instagram.

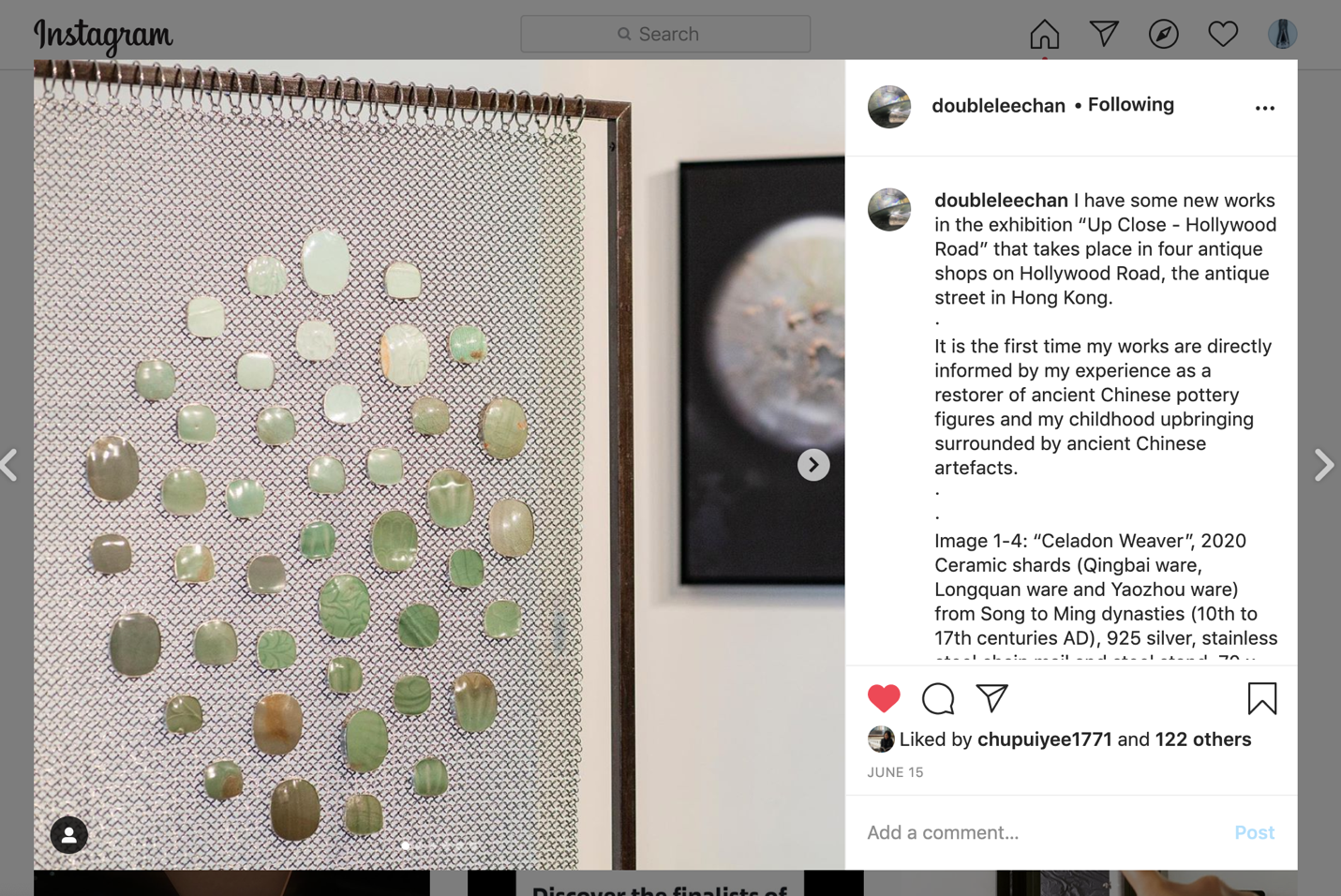

The work of Chan’s that halted my finger mid scroll was not Receptor, but a different work altogether: Celadon Weaver (2020) installed by the artist at another Hong Kong show that engaged responsively with site, Up Close – Hollywood Road (2020) [Fig. 19, bottom]. Seeing Celadon Weaver among Chinese antiquities at Gallery 149 in Sheung Wan, I recalled an experience walking through Yuen Long to the Sangwoodgoon organic farm, a project by another Hong Kong artist, Natalie Lo Lai Lai. In that walk, my eye had come to fix on a tiny polygonal cluster of light green spheres on a tiled wall. The spheres were eggs laid by a stink bug on the green tiles of a wall surrounding a village house. The cluster appeared impossibly deliberate, almost machinic. I touched it to better understand what it was. Some process of decay set into an adhesive that had discolored and bubbled? An animal intervention? Later I discovered it shared more with the termite mounds I had photographed on a research trip in Tanzania than the expandable foam I worked with on the Airstream trailer I kept in the West Texas desert. Yet, still, it seemed to share affinities with both: the technology of nature.

The Up Close show was a collaboration with various antique shops in Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan neighborhood and Chan had been invited to “explore the connection between the archaeology of the past and… archeology of the present,” exactly the temporal terrain her practice shows itself eager to engage. In Celadon Weaver [Fig. 19, bottom], jade-like forms that shimmer green are set in silver and attached to a chain mail screen that hangs from a delicate steel stand. The green material is not jade at all, but ceramic shards of Qingbai, Longquan and Yaozhou-ware that the artist collects from the 10th to 17th centuries CE (Song to Ming Dynasties). My thinking still lingered with Receptor. The sculpture, made from construction materials bought on the Chinese e-commerce site Tao Bao transformed with paper clay into a self-camouflaging entity, crosses the caterpillar from the work’s title with the Hong Kong podium-tower high-rise. The association between the two works brought me altogether elsewhere – to the hovering tiled façade of Ponti’s Shui Hing in Tsim Sha Tsui. I had forgotten about the building, and Chan’s work inspired me to return to it, in part, because of its material experiments, but also because the octagonal windows of the Po Chai Industrial Building (1975) where I had first seen Receptor [Fig. 19, top] at Blindspot Gallery, resemble Ponti’s hexagonal windows at Shui Hing. When I started gathering materials about Shui Hing – looking to see if it had been written about recently – I found references to Villa Koo listed under it (Hoyal 1997, 985). Of course, the connection with Ponti is nothing more than coincidental, but Chan’s Celadon Weaver channeled my attention to the two neglected projects [Fig. 20] through associations with my own “imaginary museum” (Malraux as cited in Grasskamp 2016, 1-2).

20 | Recent images of Gio Ponti’s Villa Koo and Shui Hing, now Prestige Tower. Source: Google Maps.

Curator Ingrid Chu has spoken to me about her conception of art as “care agent” that can create a shift in ways of conceiving the human beyond its assumed split with nature (Chu 2020). At this time of intensified biopolitical and geopolitical containment, LeeLee Chan’s practice emphasizes transformation, openness and a willful engagement with contamination. Reflecting on her process brought me to my two principle questions about Gio Ponti’s work in Hong Kong: first, what specific issues did Hong Kong force Ponti to confront in his practice and how did he use his knowledge of materials and attention to spatial and environmental relationships, to propose responses? Second, aside from bringing attention to “unrecognized projects” (Poli 2018, 252) and recognizing them, what can study of Ponti’s projects in Hong Kong reveal about the experience of building for domestic life in the city, conceiving spaces for interiority, consumption and retreat at a time of active colonial depoliticization? Contemporary artists theorize through practice and their works often bring about discoveries that they could never imagine. The political unconscious of architecture surfaces in art.

Bibliography

- Ali and Hill 2005

J. R. Ali, R. D. Hill, Feng Shui and the Orientation of Traditional Villages in the New Territories, Hong Kong, China, “Journal of the Royal Asiatic Branch“, vol. 45 (2005), 27-39. - “As It Happened” 2019

“As It Happened: How Hong Kong police fired tear gas in Tsim Sha Tsui and Mong Kok as protesters hit back with petrol bombs”, “South China Morning Post”, undated [Accessed June 30, 2020]. - Castells 1986

M. Castells, The Shek Kip Mei Syndrome: Public Housing and Economic Development in Hong Kong, Hong Kong 1986. - Carr 2004

A. K. Carr, “Department Store”, Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture, vol. 1, edited by Stephen Sennott, New York 2004, 356-357. - Celant 1990

G. Celant, “The Substantiality of the Impalpable”, Foreword in L. Licitra Ponti, Gio Ponti: The Complete Work, 1923-1978, Cambridge 1990. - Chan 1997

F. Chan, “Shui Hing Stake Sold as Losses Double”, “South China Morning Post”, November 27, 1997. - Chiu 1998

C. Chiu, Small Family Business in Hong Kong: Accumulation and Accomodation, Hong Kong 1998. - Chu 2016

C. Chu, “Narrating the Mall City.” Mall City: Hong Kong’s Dreamworlds of Consumption, edited by Stephan Al, Hong Kong 2016, 82-92. - Coleman 2020

N. Coleman, Materials and Meaning in Architecture: Essays on the Bodily Experience of Buildings, New York 2020. - Constable 1994

N. Constable, Christian Souls and Chinese Spirits: A Hakka Community in Hong Kong, Los Angeles 1994. - Chu 2020

Conversation with Ingrid Pui Yee Chu, July 11, 2020, Lamma Island, Hong Kong. - Davidson 2020

H. Davidson, “Jimmy Lai: the Hong Kong pro-democracy tycoon who is not afraid to take on Beijing”, The Guardian, August 10, 2020. - “Domus” 1961

“Domus” 385 (December 1961). - “Domus” 1968

“Domus” 459 (February 1968). - “Domus” 1970

“Domus” 484 (March 1970). - “Domus”1998

“Domus” 808 (October 1998). - Donna Moda 2020

“Donna Moda” Facebook [Accessed August 27, 2020]. - Donchin 2013

M. Donchin, The Collaborators: Interactions in the Architectural Design Process, Burlington 2013. - Easterling 2005

K. Easterling, Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and Its Political Masquerades, Cambridge 2005, 100. - Forster 1998

K. Forster, “Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference”, Dictionary of the Politics of the People’s Republic of China, edited by C. Mackerras, D. H. McMillen, A. Watson, London 1998, 69-70. - Ferguson 2020

J. C. Ferguson, Luis Barragan: A Study of Architect-Client Relationships, PhD Dissertation, University of Delaware 2000. - Gaskell 2019

V. Gaskell, Design Trust, Design Criticism: Why Hong Kong’s Buildings are Clad in Bathroom Tiles, “Zolima City Magazine”, September 26, 2019 - Grasskamp 2016

W. Grasskamp, The Book on the Floor: Andre Malraux and the Imaginary Museum, Los Angeles 2016. - Greco 2008

A. Greco, Gio Ponti: la Villa Planchart a Caracas = Gio Ponti : Villa Planchart en Caracas. Roma 2008. - Heung 2004

M. T.-Y. Heung, Walking Between Slums and Skyscrapers: Illusions of Open Space in Hong Kong, Tokyo and Shanghai, Hong Kong 2004. - Ho 2002

N. C. Ho, Firm Development in Hong Kong: A Study of the Retail Industry from the 1970’s to the 1990’s, PhD Dissertation, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 2002. - Hoyal 1997

S. Hoyal, “Gio Ponti”, Encyclopedia of Interior Design. Edited by Joanna Banham, vol. 1-2, A-Z, London 1997, 982-985. - The Hong Kong and Far East Builder 1963

The Hong Kong and Far East Builder, vol. 18, 4 (December 1963), 114-116. - Hung 2016

W. Hung, “Tycoons and Occupy Central in Hong Kong”, Tycoons in Hong Kong: Between Occupy Central and Beijing, London 2016. - Ippolito 2009

L. Ippolito, La Villa del Novecento, Firenze 2009. - “Italian Architect Designs H.K. Store” 1962

“Italian Architect Designs H.K. Store”, “South China Morning Post”, November 8, 1962. - “Italian Award for Local Resident” 1966

“Italian Award for Local Resident”, “South China Morning Post”, August 17, 1966. - Klinger 2008

K. Klinger, Relations: Information Exchange in Designing and Making Architecture, Manufacturing Material Effects Rethinking Design and Making in Architecture, edited by B. Kolarevic, K. Klinger, New York 2008. - Koo 1976

D. Koo, “Celebrating 50 Years of Service: A Message from the Chairman and Managing Director, Mr. Daniel S.C. Koo”, “South China Morning Post”, June 30, 1976. - LaMonaca 1997-1998

M. LaMonaca, Tradition as Transformation: Gio Ponti’s Program for the Modern Italian Home, 1928-1933), Studies in the Decorative Arts, vol. 5, 1 (Fall-Winter 1997-1998), 52-82. - Lange and Carlow 2017

C. J. Lange, J. F. Carlow, Cities of Repetition: Hong Kong’s Private Housing Estates, San Francisco 2017. - Lo, Leung and Lau 2020

C. Lo, C. Leung, C. Lau, “National Security Law: Hong Kong media mogul Jimmy Lai, activist Agnes Chow among those arrested as police spend nearly nine hours searching Apple Daily offices”, “South China Morning Post”, August 10, 2020. - LCQ 6 2016

“LCQ6: The Capitalist System and Way of Life in Hong Kong after 2047. A question by the Hon Nathan Law and a reply by the Under Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs, Mr Ronald Chan, in the Legislative Council”, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, press releases, December 14, 2016. - Liu 2016

C. Y. Liu, “Concepts of Architectural Space in Historical Chinese Thought”, A Companion to Chinese Art, first edition, edited by M. J. Powers, K. R. Tsiang, Hoboken 2016. - Lo 2017

Y. Lo, “Promotors – the first manufacturer of television sets in Hong Kong”, The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group, October 16, 2017. - Long 2011

C. A. Long, The Looshaus, New Haven 2011. - Lui 2001

T.-l. Lui, “The Malling of Hong Kong”, Consuming Hong Kong, edited by G. Mathews, T.-l. Lui, Hong Kong 2001, 23-46. - Mathews 2001

G. Mathews, T.-l. Lui, “Introduction”, Consuming Hong Kong, edited by G. Mathews, T.-l. Lui, Hong Kong 2001, 1-22. - Mathews 2012

G. Mathews, “Neoliberalism and Globalization from Below in Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong”, Globalization from Below: The World’s Other Economy, edited by G. Mathews, G. Lins Ribeiro, C. Alba Vega, Abdingdon 2012, 69-85. - Mautone 2009

F. Mautone, Gio Ponti e la committenza Fernandes = Gio Ponti and the Fernandes Commission, Napoli 2009. - Morris 1989

J. Morris, Hong Kong, New York 1989. - Ng 2009

J. Ng, Paradigm City: Space, Culture, and Capitalism in Hong Kong, Albany 2009. - Nightingale 2012

C. H. Nightingale, Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities, Chicago 2012. - Noack 2020

R. Noack, “Who are Jimmy Lai and Agnes Chow, two of the Hong Kong democracy advocates arrested Monday?”,“The Washington Post”, August 11, 2020. - “Opportunities for Colony’s Products in Italy” 1962

“Opportunities for Colony’s Products In Italy”, “South China Morning Post”, October 19, 1962. - Palandri 2019

A. Palandri, “La Casa Ideale. Evoluzione dell’Idea di Spazio Domestico nell’opera di Gio Ponti”, Esempi di Architettura (EdA), January 2019. - Pang 2020

L. Pang, The Appearing Demos: Hong Kong During and After the Umbrella Movement, Ann Arbor 2020. - Poli 2018

S. A. Poli, “Gio Ponti’s Unrecognized Architecture.” Gio Ponti: Archi-Designer, Milano 2018, 252-255. - Ponti 1961

G. Ponti, “A ‘Florentine’ Villa: House for Anala and Armando Planchart in Caracas”, “Domus” 375 (February 1961). - Ponti 1957

G. Ponti, Amate L’Architettura: L’Architettura è un Cristallo, Genova 1957. - Ponti 1990

L. Licitra Ponti, Gio Ponti: The Complete Work, 1923-1978, Cambridge 1990. - Ponti 2005

L. Licitra Ponti, “Gio Ponti, Hong Kong, e il committente cinese = Gio Ponti, Hong Kong and the Chinese Client.” Abitare 450 (January 2005), 164-167. - Ramanath 1971

K. R. Ramanath, “HK Mission off to Italy,” South China Sunday Post – Herald, May 9, 1971. - Ramzy and May 2020

A. Ramzy, T. May, “Hong Kong Arrests Jimmy Lai, Media Mogul, Under National Security Law”, The New York Times, August 10, 2020. - Redmond 2008

S. Redmond, Studying Chungking Express, New York 2008. - Rendell 2017

J. Rendell, The Architecture of Psychoanalysis: Spaces of Transition, London 2017. - Rendell 2011

J. Rendell, “May Mo(u)rn: A Site-Writing”, The Political Unconscious of Architecture: Re-opening Jameson’s Narrative, edited by N. Lahiji, New York 2011, 109-142. - Rooney 2003

N. Rooney, At Home with Density, Hong Kong 2003. - Scarpellini 2008

E. Scarpellini, Material Nation: A Consumer’s History of Modern Italy, Oxford 2008. - Schnapp 2004

J. T. Schnapp, Building Fascism, Communism, Liberal Democracy: Gaetano Ciocca – Architect, Inventor, Farmer, Writer, Engineer, Stanford 2004. - Seng Docomomo 2020

E. Seng, “3-Storey House, 20 Kadoorie Avenue”, Docomomo [Accessed June 30, 2020]. - Seng 2020

E. Seng, Resistant City: Histories, Maps and the Architecture of Development.“Domus” Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2020. - Shapiro 2020

A. Shapiro, “Hong Kong Police Arrests A Prominent Pro-Democracy Figure”, NPR, August 10, 2020. - “Shui Hing Co Ltd” 1993

“Shui Hing Co Ltd”, Major Companies of the Far East and Australasia 1993/1994, vol, 2: East Asia, edited by J. L. Carr, London 1993. - Space Design 1981

Space Design, vol. 200, 1981 (monographic issue: Gio Ponti). - Stein 1996

P. Stein, “’Angry, Hungry Eyes’: Hong Kong Crime Spree Has Roots Across Border”, “Asian Wall Street Journal”, August 1996. - Tong 2019

E. Tong, “In Pictures: Police-Protester Skirmishes Across Hong Kong, as Officers Clear Tsim Sha Tsui with Tear Gas”, “Hong Kong Free Press”, August 11, 2019. - Wong 2020

B. Wong, “Hong Kong Media Tycoon Jimmy Lai and 12 Others Face Incitement Charges Over June 4 Tiananmen Vigil”, “South China Morning Post”, July 13, 2020. - Wong 1993

J. Wong, “Debate on Reform Divides Hong Kong – Patten’s Proposals Raise Questions About Courage, Patriotism and Profits”, “Asian Wall Street Journal”, January 11, 1993, 1. - Wong 2019

H.-W. Wong, K. L.-F. Chau, Tradition and Transformation in a Chinese Family Business, London 2019. - Wong 2015