Unbounded freedom ruled the wandering scene

Nor fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect of the following eye

Its only bondage was the circling sky.

John Clare, The Moors

1 | John Constable (1776–1837), Ploughing Scene in Suffolk, Oil on canvas, England, 1824-25, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.41., CC0.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Enclosure Movement swept through rural England. Common lands that had been open for communal use were fenced off, privatised and controlled by a few landowners. For local citizens and communities, this meant the loss of access to shared land and resources that had sustained them for generations. While precise figures for population decline in every village affected by enclosure are difficult to determine due to the limitations of historical records, the overall impact was significant. J.M. Neeson estimates that between 1750 and 1820 as much as 30% of agricultural land in England was enclosed by an Act of Parliament (Neeson 1993, 328). Villages experienced substantial changes in their social structure as families were forced to migrate to urban centres in search of work.

Advocates for enclosure, like Arthur Young, praised its efficiency gains (Young 1770, 252-264), while critics such as William Cobbett and John Clare highlighted enclosure’s devastating social consequences (Cobbett [1830] 1985, 176; Clare 1820, 169). What had been freely accessible land became restricted, turning shared resources into private property. This transformation displaced communities, disrupted livelihoods and concentrated power in the hands of a few. Enclosure fundamentally reshaped the relationship between people and the commons.

Just as enclosure privatised communal lands, many early museums emerged from the private collections of elites, consolidating cultural artefacts into managed spaces. These institutions, often born of colonial acquisitions or aristocratic patronage, centralised heritage itself and the ways in which it was organised, mirroring the loss of shared access to land (Aldrich 2009, 137–156). Artefacts once integral to communal or ceremonial life were removed and recontextualised within curated environments, far from their original contexts.

The Digital Enclosure of Cultural Heritage

In the realm of museums, the rise of digitisation has been celebrated as a way to democratise access to culture. By putting artworks, manuscripts and artefacts online, museums promised to make these treasures accessible to anyone with an internet connection (European Commission 2010). In practice, however, access is frequently granted under restrictive terms that limit the use and reuse of these digital resources. A phenomenon reminiscent of enclosure has unfolded in the digital realm, particularly concerning when these restrictions are applied to digital reproductions of works that are themselves in the public domain.

This practice disrupts the fundamental principles of copyright, which grants creators exclusive rights for a limited time to encourage creativity. Once this period expires, works enter the public domain, becoming a shared cultural resource, freely available for public access, use and reinterpretation. The public domain plays a crucial role in fostering innovation, education and the creation of new works, allowing artists, writers and scholars to build upon the foundations laid by previous generations. It ensures that knowledge and culture are not indefinitely locked away behind paywalls but can be freely accessed and used to inspire new creative endeavours. However, many institutions use copyright and contract law to assert control over digitised public domain collections, such as centuries-old paintings, medieval manuscripts and historical photographs. In most jurisdictions, the legal basis for asserting copyright over straightforward digital reproductions of public domain works is highly questionable, as such reproductions typically lack the originality required for copyright protection. By effectively extending copyright beyond its intended limits, these institutions are creating an artificial scarcity that hinders the free flow of information and creativity, contradicting the very purpose of the public domain.

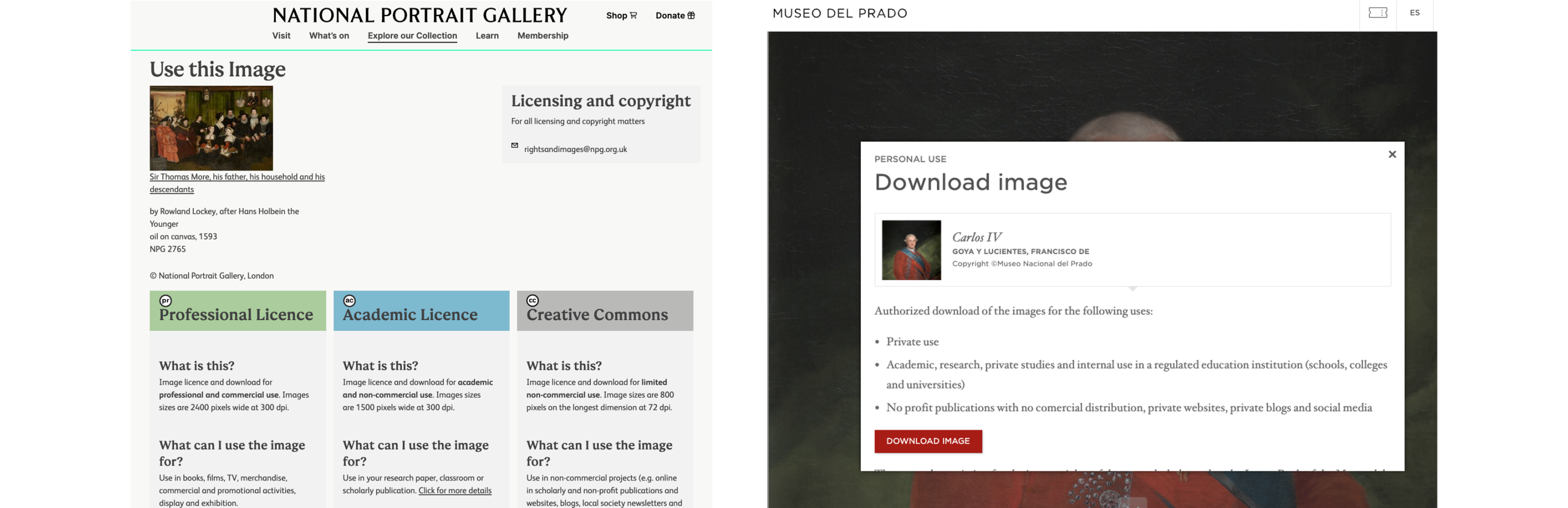

2a | Screenshot of the National Portrait Gallery’s website, highlighting copyright assertion and complex licensing framework.

2b | Screenshot of the Museo del Prado website, indicating its authorised forms of ‘personal’ image use.

In addition to legally dubious copyright assertions, many museums impose licensing fees and restrictive terms of use on their digital assets, even for educational and non-commercial purposes. London’s National Portrait Gallery, for instance, claims copyright in its digital images of public domain artworks and has three similar but distinct licences covering the spectrum of commercial to non-commercial use (National Portrait Gallery 2025). The Museo del Prado also claims copyright in images of works by long-dead artists and allows free use for a narrow range of non-commercial “personal use” (Museo del Prado 2025). Restricting access to digitised cultural heritage has far-reaching consequences. Scholars, educators and artists face significant hurdles when attempting to use these resources, especially financial barriers.

The British Museum charges £100 to reproduce a public domain artwork (in which it claims copyright) in an online academic publication, for an unlimited time period (British Museum 2025). The cumulative effect of such fees becomes apparent when considering that costs rise significantly with print runs and expanded territorial rights, quickly making image-rich publications prohibitively expensive. In 2019, the art historian Professor Kathryn Rudy calculated she had spent £24,000 in less than a decade of publishing articles and books, writing in the “Times Higher Education” that ‘the more I publish, the poorer I am’ (Rudy 2019). Image fees impose financial strain on scholars, particularly those in the early stages of their careers or working with limited budgets. The cost of acquiring licences for numerous images can rapidly become prohibitive, compelling researchers to make difficult decisions about which artworks to include in their publications. In some cases, these fees even influence the choice of research topics, as scholars may be forced to avoid areas that require extensive use of images.

The financial implications of these restrictive practices are far-reaching and exacerbate existing economic inequalities. While individual researchers, authors and artists in high-income countries bear a significant burden, the impact is even more detrimental to individuals and institutions in low- and middle-income countries. Licensing fees can quickly deplete already limited budgets, hindering their ability to create exhibitions, develop educational programmes, engage in digital outreach or support local scholarship. This disparity effectively creates a two-tiered system of access to cultural heritage, where institutions and scholars in less affluent nations are disproportionately disadvantaged. Moreover, by throttling access to digital reproductions, museums limit the range of perspectives and narratives that can be shared about art and history, leading to a narrower, more homogenous understanding of our collective cultural heritage and potentially excluding marginalized voices and alternative interpretations. This risks creating a chilling effect on scholarship and public discourse, ultimately undermining the very purpose of cultural institutions as stewards of shared heritage.

Lessons from History: The Impoverished Commons

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his essay Nature, lamented the loss of access to shared natural spaces as part of broader societal trends of privatisation and individualism (Emerson 1836). Emerson’s reflections resonate deeply with today’s cultural enclosures, where control over digitised heritage is maintained by institutions rather than shared openly. As the historian and critic Tyler Green noted in the foreword to his book Emerson’s Nature and the Artists:

Nothing restrains our knowledge of how art and artists have engaged with and impacted broader histories than the absurd rights fees that most art museums, libraries and other institutions charge to publish pictures of out-of-copyright art (Green 2021, 31).

The enclosure of cultural works invites critical questions about access, ownership and the role of memory institutions. Museums that impose restrictions on digitised public domain materials risk undermining their public mission and betraying the trust placed in them as stewards of collective memory.

Commodification of the Commons: NFTs and Public Domain Art

The rise of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) in 2021-23 added another layer of complexity to the debate over digital enclosures and public domain heritage. Several world-famous museums entered commercial partnerships to create and sell NFTs of masterpieces in their collections, a move that, at first glance, might seem to embrace new technology and potentially wider audiences. However, a closer look reveals a more concerning trend. The museums that most readily experimented with NFTs – including the State Hermitage Museum, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, the Uffizi Galleries and the British Museum – were also, typically, institutions with highly restrictive access policies regarding their digital collections. These were the very same museums that leverage both copyright and contract law to exert control over digital images of public domain works, imposing restrictive licensing fees, even for non-commercial use.

This was no coincidence, but a revealing indicator of a broader strategy. Rather than a genuine effort to democratise art, these museums’ forays into the NFT market appear to be driven by a desire to further monetise and control their digital assets, even those based on public domain works. Instead of opening up their collections, these NFT projects represented an extension of their existing restrictive practices into a new digital realm. It demonstrated that the underlying motivation was not to share cultural heritage freely but to find new avenues for asserting ownership and generating revenue. These NFT ventures, therefore, served to highlight the fundamental tension between a museum’s role as a public institution and the desire to commercialise and control cultural assets. The move raised ethical questions about whether these institutions were prioritising profit over their public mission to preserve and share cultural heritage (Deakin 2023).

Resisting Enclosure: Open GLAM and the Digital Commons

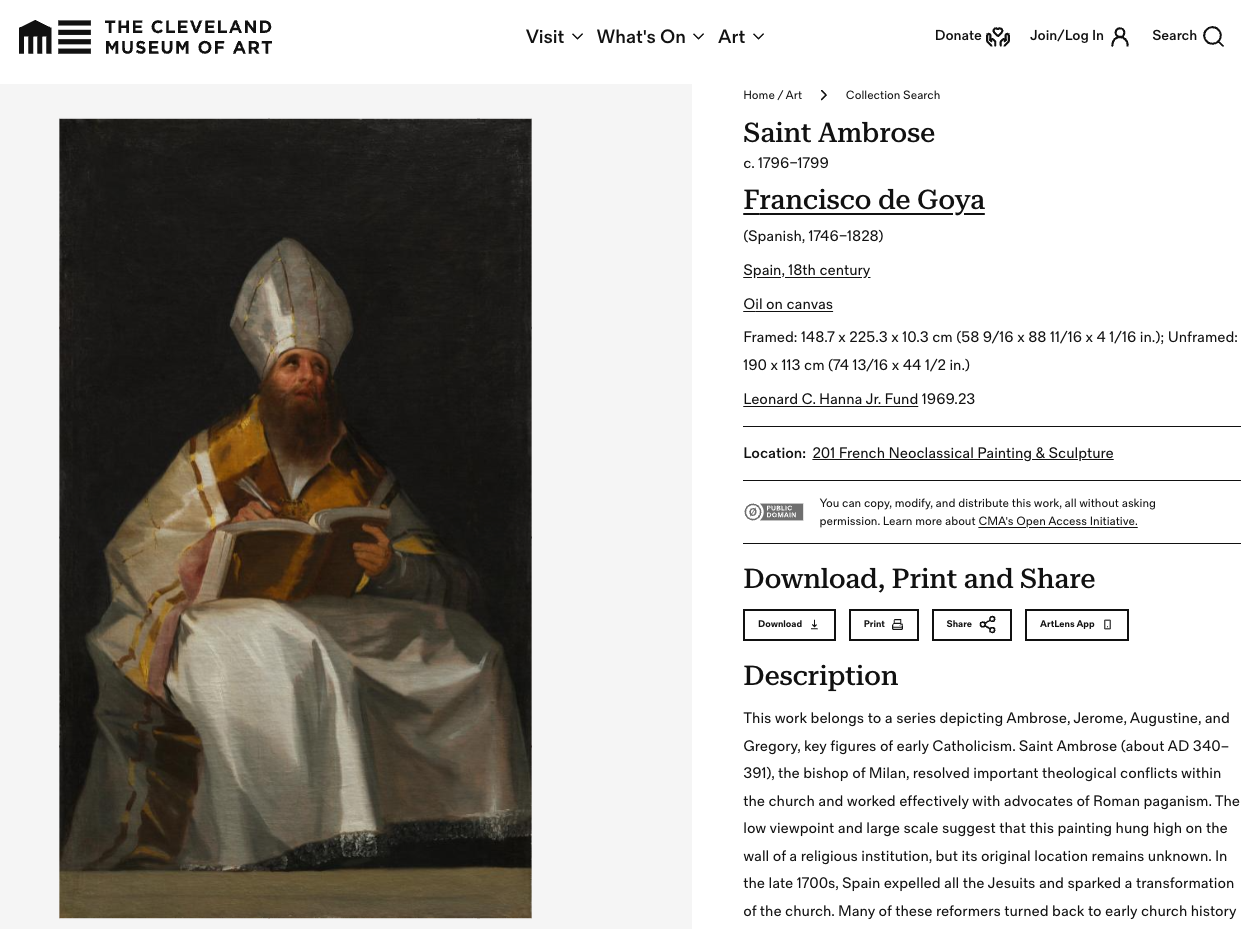

3 | Screenshot of image on the Cleveland Museum of Art’s website, demonstrating open access to a high-resolution image made available under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) designation.

4 | Member institutions of the TAROCH Coalition, Creative Commons, image of Logos of TAROCH Coalition, CC BY 4.0.

Despite the prevailing trend of digital enclosure described above, the case for open access to public domain heritage has been gaining ground. For two decades, the Open GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums) movement has actively challenged this enclosure by advocating for the free sharing of cultural heritage collections and data while respecting ethical considerations, such as the sensitive handling of culturally significant materials and appropriate consultation with communities of origin. Open GLAM has gained significant momentum, as evidenced by the growing number of institutions adopting open access policies, the development of supporting infrastructure and tools and the advocacy efforts of a global coalition of organisations. The Open GLAM Survey has recorded over 1,600 institutions worldwide with some form of open access initiative (McCarthy, Wallace 2025). A growing number of major institutions offer high-resolution downloads of their public domain collections for free, demonstrating a commitment to open access principles. While precise figures are difficult to track comprehensively, over 98 million digital objects from cultural institutions have been made freely available online to date (McCarthy, Wallace 2025). This continuing growth demonstrates a clear shift within the cultural heritage sector towards greater openness and a recognition of the public benefits of sharing digital collections widely.

Beyond individual institutions adopting open access policies, broader initiatives are providing crucial support at a systemic level. For example, Wikimedia affiliates and projects around the world, such as local chapters in Côte d’Ivoire, Colombia, Armenia and Argentina, are driving the digitisation of cultural heritage and making these digital resources freely available online under open licences. (GLAM Wiki 2025). Projects such as TAROCH (Towards a Recommendation on Open Cultural Heritage), a collaborative effort to achieve the adoption of a UNESCO standard-setting instrument to improve open access to cultural heritage, and the GLAM-E Lab Open GLAM Toolkit, which offers practical resources and guidance for implementing open access, are helping to drive change (Creative Commons 2024; GLAM-E Lab 2024). These initiatives are supported by a growing global coalition that extends beyond the GLAM sector, including open society and open data advocates. Organisations such as Communia Association, the Open Knowledge Foundation and Creative Commons have long championed the principles of open access, working to promote policies and infrastructure that enable the free flow of information and knowledge. For example, Creative Commons provides a suite of legal tools and licences that allow creators to share their work completely openly, or while retaining certain rights, while the Open Knowledge Foundation develops tools and resources for open data initiatives (Creative Commons 2025; Open Knowledge Foundation 2025). Communia focuses on advocating for copyright reform that supports the public domain and open access (Communia 2025). The combined efforts of these organisations, along with those of Open GLAM advocates, legal experts and museum professionals involved in such projects, are creating a powerful movement towards a more equitable and participatory cultural landscape where knowledge is freely shared, reused and built upon to foster creativity and innovation.

Complementary to these initiatives, digital commons repositories such as Wikimedia Commons, Europeana and cultural heritage aggregators provide shared infrastructures for managing cultural assets collaboratively and openly, and fostering public engagement. These platforms demonstrate the practical possibilities of open access, providing models for how cultural heritage can be made freely available and reusable, while respecting ethical considerations and the rights of creators where applicable.

Conclusions

The digital enclosure of cultural heritage mirrors the historical Enclosure Movement, with similarly profound consequences. While museums face legitimate funding challenges in maintaining their collections and operations, many in the cultural heritage sector, including myself, believe that relying on licensing fees for public domain images is not a sustainable or ethical long-term solution. In fact, I have argued that such restrictive licensing practices often generate negligible revenue, while open access policies can drive significant financial and mission-based benefits for institutions (McCarthy 2024). My research suggests that many museum image libraries operate at a loss. Furthermore, open access can lead to increased visibility, wider reach, new opportunities for collaboration and enhanced public engagement, ultimately helping museums to better fulfill their core mission.

Moving away from a reliance on restrictive licensing requires exploring alternative funding models, such as increased public funding, philanthropic support and innovative revenue streams that do not restrict access. Beyond traditional membership programmes and business partnerships, many museums are exploring opportunities in areas like digital storytelling, online education and creative collaborations with artists and designers that leverage openly-licensed digital collections. Some institutions have successfully implemented open access policies while maintaining financial stability, demonstrating that these goals are not mutually exclusive. However, the persistence of restrictive licensing practices continues to create a two-tiered system of access to cultural heritage, disproportionately impacting scholars and institutions in countries with fewer resources. The broader cultural and educational benefits of open access, including fostering creativity, innovation and public engagement, should be central to discussions about the future of museums and their role in the digital age. Therefore, it is imperative that museums, policymakers, funders and the public actively support open access initiatives, challenge restrictive licensing practices and work together to create a digital cultural landscape where public domain heritage is freely available to all, regardless of geographical location or financial means.

Bibliography

Bibliographical References

- Aldrich 2009

R. Aldrich, Colonial museums in a postcolonial Europe, “African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal”, vol. 2 (2009), 137-156. - Clare 1820

J. Clare, The Mores, in John Clare: Selected Poetry, London 1990, 169. - Cobbett [1830] 1985

W. Cobbett, Rural Rides in the Counties of Surrey, Kent, Sussex, Hampshire, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Somersetshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk and Hertfordshire; republished as Rural Rides, London 1985, 176. - Deakin 2023

C. Deakin, Museums and NFTs: what’s the opportunity, who’s doing it best and why question marks remain, “Museum Next”, 19 September 2023. - Emerson 1836

R.W. Emerson, Nature, Boston 1849. - Green 2021

T. Green, Emerson’s Nature and the Artists: Idea as Landscape, Landscape as Idea, London 2021. - Neeson 1993

J.M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820, Cambridge 1993. - Rudy 2019

K.M. Rudy, The true costs of research and publishing, “Times Higher Education”, 29 August 2019. - Young 1770

A. Young, The Farmer’s Tour Through the East of England, London 1770.

Online Resources

- British Museum 2025

British Museum Images. - Communia 2025

Communia website, 2025. - Creative Commons 2025

Creative Commons website, 2025. - European Commission 2010

European Commission, A Digital Agenda for Europe, 2010. - GLAM Wiki 2025

GLAM Wiki website, 2025. - GLAM-E Lab 2024

GLAM-E Lab, Open GLAM Toolkit, 2024. - McCarthy 2024

D. McCarthy, Balancing access and income – the dilemma of museum image licensing, 2024. - McCarthy, Wallace 2025

D. McCarthy, A. Wallace, Open GLAM Survey, 2018-2025. - Museo del Prado 2025

Museo del Prado website. - National Portrait Gallery 2025

National Portrait Gallery website. - Open Knowledge Foundation 2025

Open Knowledge Foundation website. - Creative Commons 2024

Creative Commons, TAROCH (Towards a Recommendation on Open Cultural Heritage), 1 November 2024.

English abstract

This article examines how many museums are restricting access to digital images of public domain artworks, a practice likened to the historical Enclosure Movement in England. It argues that this “digital enclosure” limits scholarship, education and creative reuse, undermining the natural state of the public domain. The article analyses the legal and ethical implications of these practices, particularly in relation to copyright claims over digital reproductions. It also explores the irony of museums with restrictive access policies embracing NFTs as a new form of monetisation. The article further highlights the resistance to this trend, exemplified by the Open GLAM movement, and the efforts of organisations like Creative Commons and Wikimedia Foundation affiliates, along with projects like TAROCH, to promote open access. By advocating for alternative funding models and greater collaboration, the article calls for a shift towards a more open and equitable digital cultural landscape, where public domain heritage is freely shared and accessible to all.

keywords | Digital Enclosure; Public Domain; Open Access; Copyright; Cultural Heritage.

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: Douglas McCarthy, Museums and the Enclosure of the Public Domain in the Digital Age, “La Rivista di Engramma” n. 222, marzo 2025, pp. 173-180 | PDF