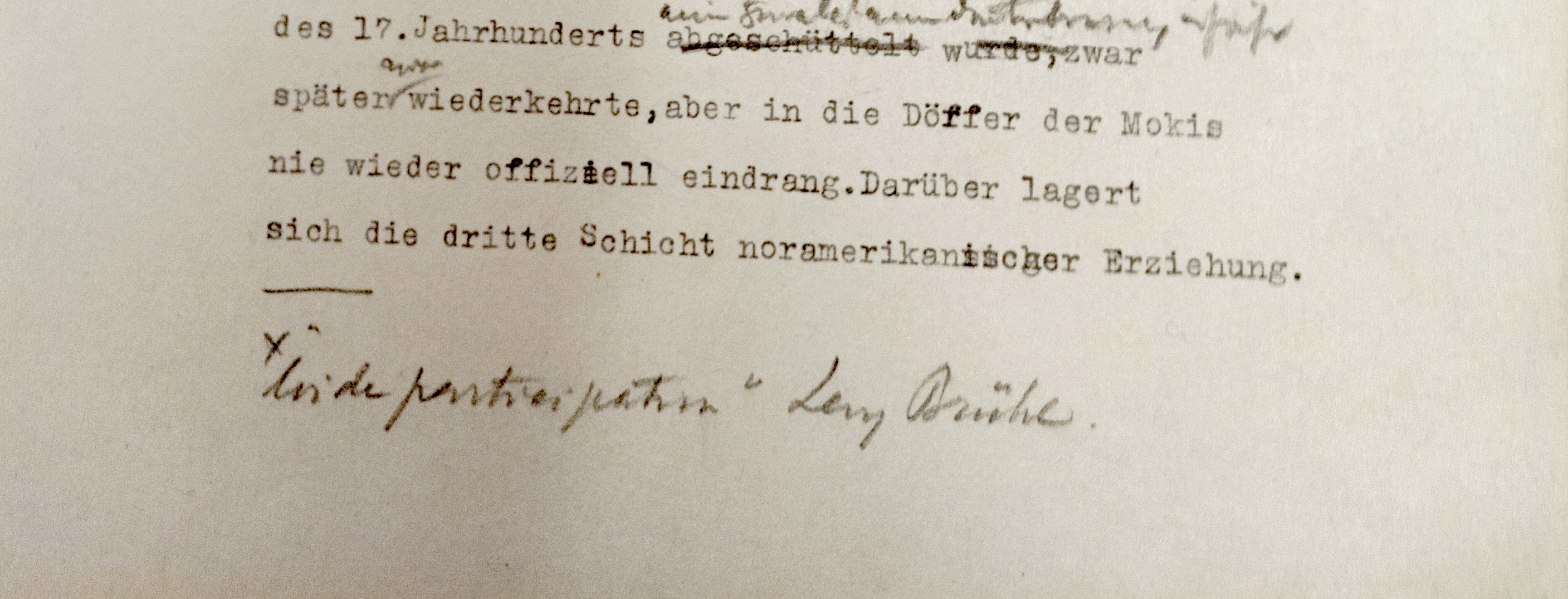

Footnote in the typescript of Bilder aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo-Indianer in Nord-Amerika, with reference to Lévy-Bruhl’s loi de participation [WIA III 93.1, fol. 2].

Anthropology

The first thorough analysis of how anthropology was present in the thought of Aby Warburg (1866–1929) pertains to the text written by his assistant and successor as director of the Library, Fritz Saxl (1890–1948), presented just a few months after Warburg’s death, at the XXIV Congress of American Anthropology. In the text, titled Warburg’s Journey to New Mexico, Saxl highlights Aby Warburg’s awareness of the decisive role anthropology played in his work. In Saxl’s own words:

Aby Warburg, the founder of the Warburg Institute, was in the middle of making plans for the organisation of the Twenty-Fourth Congress of American Anthropology when he died on 26th October, 1929. He had been looking forward to this Congress with great expectations, for by inviting it to meet on the premises of his library he had intended to repay an old debt. He had felt himself under a deep obligation towards American ethnologists ever since his return in 1896 from a visit to the United States which had played a decisive part in his life. It is not immediately clear why this should be so. A casual visitor will find only a small number of books in the library and few pictures in the photographic collection which bear directly on anthropological studies. With its four main sections on history of art, of religion, natural science and philosophy, of language and literature, and on political and social history the library looks as if it were designed for the study of the history of civilisation in general […]. [The Library] serves special rather than general problems; and it aims at completeness only where these are concerned. One of them—and this is in fact our central problem—is the question of how classical antiquity affected the mediaeval and modern civilisations of the Mediterranean […]. Why then should it include American anthropology at all, and why should this, in the founder’s opinion, even be necessary? I believe my best way to explain this is to describe Warburg’s own development. This is not merely a biographical matter; for the growth of the library goes hand in hand with that of Warburg’s personality and ideas […]. For what Warburg owed to America was that he learned to look at European history with the eyes of an anthropologist (Saxl [1930] [1957] 2023, 183).

In the following decades, the relationship between Warburg’s studies and anthropology was hinted at on various occasions by different scholars examining the critical reception of his work. However, the interest in a Warburg as an “anthropologist of the image” became more explicit from the 2000s onward. In this context, the Italian scholar and professor in France (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales – EHESS), Carlo Severi, sought to establish close connections between Warburg’s reflections and anthropological knowledge in a 2003 article. According to Severi, there are several foundational elements in Warburg’s inquiry into visual objects that align with distinctly anthropological matters: “The cultural difference and the ‘dividing line’ that mark different societies across time and space, the ritualized expression of emotions, the relationship between the origins of iconographies and ritual action, the construction of the image of a ritual memory” (loosely translated from Severi 2003). Rather than specifically categorizing Warburg’s work as anthropological, Severi highlights a gap in the critical reception of his writings. According to the Italian anthropologist, Warburg developed a strategy to analyze images that bring to light the need to restore the full historical and cultural complexity to iconographic traditions, situating his reflections at the intersection of art history, the history of ideas, psychology of vision, and anthropological research. However, the anthropological aspect of his work had not been revisited within the tradition of studies inspired by the Warburg Institute. “Not only did no one imagine following the path Warburg outlined, but the very existence of an anthropological aspect in his thought has long been sidelined by his successors”, Carlo Severi observes (Severi 2003, 87).

This perspective is also shared by Hans Belting, both in his book Bild-Anthropologie. Entwürfe für eine Bildwissenschaft (Belting 2001) and in a later article published in Brazil in 2005, Por uma antropologia da arte (Belting 2005). According to Belting, Aby Warburg developed an anthropology of images that encompassed both Western and non-Western images, a scientific and cultural operation which, however, he argues, was interrupted by his followers, who transformed it into an artistic-historical method: iconology. This critique is explicitly directed at Erwin Panofsky and Edgar Wind, who are specifically named. With his Bild-Anthropologie, Belting aims to establish a line of continuity with Warburg’s Kulturwissenschaft (science of culture), as his Anthropology of Image is defined by a term contemporary with the one coined by the Hamburg scholar: Bildwissenschaft—science of image.

In line with the discussion brought forth by Hans Belting is the article by David Freedberg, which reiterates the difficulty of establishing clear boundaries between the domains of anthropology and art history. Freedberg, who served as Director of the Warburg Institute in London from 2015 to 2017, goes so far as to assert that “the ethnography of art and the worlds of art are typical of both art history and anthropology”, and, therefore, “much of what is considered anthropology of art is, in reality, common practice among art historians” (loosely translated from Freedberg 2008, 8). Starting from the premise that an art historian must also be an anthropologist, Freedberg is explicit in advocating for an integration of the two disciplines:

The main areas of interest in art history concern the production, consumption, and circulation of artworks within society, specifically in their social context. One investigates both the practice and practices of art, encompassing the artist’s workshop as well as the art market; one examines issues related to the aesthetic status of artworks in society, their use, and the relationships they establish both among themselves and with other types of images circulating within a society or imported from abroad. At the same time, art history can shift its focus to other types of images and works that do not qualify as artworks in the strict sense, following the methods of the new subject of visual culture (Freedberg 2008, 5).

This passage describes the field of art history to highlight its integration with anthropology, emphasizing the absence of boundaries between these two humanistic disciplines. Significantly, however, Freedberg’s description could easily align with a definition of the scope and interests encompassed by Aby Warburg’s research on images. It is in this sense that, some years later, in 2014, in the introduction to a book compiling essays by various Italian scholars under the title Aby Warburg, antropologo dell’immagine, Elisabetta Villari presents Warburg as a precursor of the dialogue between art history and anthropology, framing the latter as the study of all visual expressions within the context of specific cultural conditions (Villari 2014, 13).

Thus, the discussion about the role of anthropology in Warburg’s investigations was established, while simultaneously affirming the difficulty of defining clear boundaries between art history and the anthropological discipline within contemporary research on images.

“Loi de participation”

Indeed, throughout his career, Aby Warburg maintained an intellectual dialogue with anthropology, which had recently emerged as an autonomous discipline, as well as with some prominent anthropologists who were active between the late nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century. Particularly emblematic in this regard is the connection he established with the work of the French anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Brühl (1857–1939). This engagement is often cited due to a reference in the lecture Warburg delivered in 1925, one of his most significant texts on the subject of astrology (loosely translated from Warburg [1925] 2018). In this case, the reference pertains to the concept of “loi de participation [law of participation]”, immediately indicated in Lévy-Brühl’s 1922 book, La mentalité primitive (Lévy-Brühl 1922). However, the book in which the French anthropologist originally conceived the loi de participation is the one published in 1910, Les Fonctions Mentales dans les Sociétés Inférieures (Lévy-Bruhl 1910), whose chapter II is titled precisely La loi de participation. The first reference to this concept in Aby Warburg’s writings predates 1925, appearing in his 1923 notes for the lecture he delivered on April 21 at the Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen, Switzerland, where he reflected on his trip to the United States in 1895–1896. These notes, made public in various versions (for the complex editorial history of the two texts, see the monographic issue of Engramma: De Laude, Ferrando 2023), were edited in the volume organized by Martin Treml and Sigrid Weigel under the titles Bilder aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo-Indianer in Nord-Amerika (“Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America”; WEB, 524-566) and Reise-Erinnerungen aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo-Indianer in Nordamerika (“Travel Memories from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America”; WEB, 567-602).

Let us begin, however, with the case of the 1925 lecture. In Die Einwirkung der Sphaera Barbarica auf die kosmischen Orientierungsversuche: Franz Boll zum Gedächtnis (“The Influence of the Sphaera barbarica on Western Attempts at Cosmic Orientation. In Memory of Franz Boll”), Warburg references the concept of the “law of participation”, which is central to Lévy-Brühl’s effort to uncover the meaning of causality among “primitive” peoples. In Warburg’s words:

In sociology, there is now discussion of a fundamental law, the loi de participation (that is, of the “consciousness of a fluid boundary between the Self and the environment”, Lévy-Brühl), which should be particularly characteristic of the mental functions of primitive man (Warburg [1925] 2018, 155).

And Warburg immediately references, in a footnote, Lucien Lévy-Brühl’s book La mentalité primitive, published in 1922 (Warburg [1925] 2018, 155). It is a fundamental passage to understand the intricacies of Warburg’s interpretation of the theme of astrology, and the importance that Lévy-Brühl’s mentioned concept holds within it.

In the passage quoted above, it is significant that Warburg, while referencing the book, also asserts that the law of participation is “particularly characteristic of the mental functions of the primitive man”. The term “mental functions” appears in the title of Lévy-Brühl’s work, where the notion of “law of participation” was first developed. In Les Fonctions Mentales dans les Sociétés Inférieures, published in 1910, the anthropologist dedicates an entire chapter to the subject. This suggests that Warburg was likely following the development of this concept in Lévy-Brühl’s writings from its inception, even though in his 1925 lecture he only references its appearance in La mentalité primitive (1922).

With the publication of Les Fonctions Mentales dans les Sociétés Inférieures, Lucien Lévy-Brühl inaugurated a new phase in his work, which had until then been characterized by reflections in the philosophical domain, the field of his original education. In his early books, he had focused on the thought of Auguste Comte, on Hegel’s theory of the state, and on the philosophy of Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi. From 1910 onward, however, ethnography began to provide the methodological foundation for his studies, now aimed at understanding the diametrically opposed characteristics of European and “pre-logical” or “primitive” mentalities. Lévy-Brühl adopted Émile Durkheim’s concept of “collective representation”, already present in Les règles de la méthode sociologique (Durkheim 1895), and applied it to the investigation of “primitive societies” (Lévy-Brühl 1910, first chapter Les représentations collectives dans les perceptions des primitifs et leur caractére mystique). For Lévy-Brühl, among Europeans, the notion of representation, even when immediate or intuitive, entails a duality within unity, for it conceives the cognizable object as separate from the cognizant subject. In the case of “primitives”, however, according to Lévy-Brühl one can observe that their mentality does something beyond merely representing its object: it possesses it and is possessed by it. Its meaning is, at once, physical and mystical. The primitive man simultaneously thinks and experiences the represented object (see Goldman 1994; de Oliveira 2002). From this arises the “law of participation”, as defined by the anthropologist in the second chapter of his 1910 book: “participation is so genuinely lived that it is not properly thought” (Lévy-Brühl 1910). In other words, in “primitive mentality”, according to Lévy-Brühl, there is no separation between subject and object in representation. On the contrary, the “primitive man” establishes a relationship with both nature and artifacts in which his individuality expands and merges with these elements, forming a singular, mystical, interpenetrated sphere. Thus, artifacts and animate and inanimate beings are imbued with mystical properties, establishing with man a single sphere of mutual participation. From this sphere of mutual participation, in which man simultaneously represents and experiences the world, the French anthropologist conceived the notion of “pre-logical thought”. It is this kind of pre-logical cognitive law, according to which these representational connections shape the reasoning of “primitives”, that he termed “law of participation”.

The “law of participation” thus becomes the very principle of primitive mentality, characterized as a mystical potentiality, conceived by Lévy-Brühl in opposition to logical potentiality, the latter being the foundation of the cognizant process of the European man. This notion was already fully developed in Les Fonctions Mentales dans les Sociétés Inférieures, therefore twelve years before it reappeared as a defining element of causality among the “primitives” in La mentalité primitive.

Aby Warburg, however, references the notion of loi de participation as it appears in Lévy-Brühl’s 1922 book, La mentalité primitive. On that occasion (April 25, 1925), Warburg delivered a lecture at the Hamburg Library in honor of the philologist Franz Boll, which he titled Die Einwirkung der Sphaera barbarica auf die kosmischen Orientierungsversuche des Abendlandes. Franz Boll zum Gedächtnis (“The Influence of the Sphaera barbarica on Western Attempts at Cosmic Orientation. In Memory of Franz Boll”). In the lecture, Warburg addressed a cultural-historical problem that he himself defined as:

The possibility of understanding the restoration of Antiquity as an attempt (perhaps not aesthetically alluring, but one that binds us even more profoundly to the human) to liberate the modern personality from the spell of the Hellenistic magical practice (Warburg [1925] 2018, 144).

Astrology

For Warburg, astrology is the essential testimony for the History of Culture, at the brink of the Modern World, of how humanity creates mental tools to locate itself within the universe. To this end, Warburg employs the concept of Denkraum (space of thought), aiming to demonstrate, through words and images, how Greek math, when reintroduced into the realm of knowledge during the Renaissance, provided humanity with a weapon against the conceptions of astral demons originating from Asian Greece, which had permeated the Western astrological imagination throughout the Middle Ages.

Warburg’s Greece is understood as a cultural meeting ground marked by tensions. Astrology itself represents the significant extension of this field of forces. It reached the Renaissance man through a transmission that, in turn, carried elements originating from the Late Antique Indian, and medieval Arab and Spanish worlds (Warburg had previously addressed this in his 1912 lecture Italienische Kunst und international Astrologie im Palazzo Schifanoia zu Ferrara: Warburg 1922). Thus, the numerical mathematical principle that originally characterized Greek astronomy is transformed by its contact with Late Antique magic. The magic manifests as an applied cosmology, ultimately culminating in a manipulative practice of the principle of equality between subject and object. Hence, man, understood as a microcosm, is conceived by the astrologer in direct relation to the world of the stars, in an era predating the invention of the microscope. The iconography of the “Zodiac Man”, a recurring representation in the Latin Middle Ages, exemplifies this process. It is a product of a relational understanding between man and the cosmos, an image that illustrates, through the phenomenon known as “melothesia”, how astral configurations influence each organ of the human body. It is a worldview expressed through philosophy and medicine that is also present in late-medieval astrology.

In his 1925 lecture, Warburg seeks to understand (in dialogue with the knowledge brought forth by the Anthropology of that time) the process that led to the astrological comprehension of the anthropomorphization of the cosmos—governed by sacrifices, knowledge derived from “livers of divination” (hepatology)—towards the contemplation of the celestial sphere through the erudition made possible by the contact with pagan knowledge. Hence the motto he adopts from Franz Boll: “Per monstra ad sphaeram!” (From monsters to the sphere!). This journey moves from the legacy of Teucer’s Sphaera barbarica, which persisted in the role it played in medieval and early Renaissance astrology through the Great Introduction (the work of the ninth-century Arab scholar Abu Ma’shar), to the discovery of the sphere by the Renaissance astronomer. The discovery of the sphere symbolized the conquer of Antiquity by Renaissance astrology/astronomy. This is the path of the Renaissance seen as a cultural-historical time, and therefore a transitional period bridging the Middle Ages and the Modern World.

Still in his 1925 lecture, Warburg turns his attention to Kepler, who, in Mysterium Kosmographicum (1569), conceived a solid system of nested regulars fitting to one another, representing the symbolic image of the spheres. He also references Kepler’s letter, in which the astronomer argues regarding the ellipse:

Kepler, in his 1608 correspondence with Fabricius, argued vigorously against him, asserting that the ellipse is, in itself, a mathematical idea not subordinate to the circle in terms of perfection. Thus, with the introduction of the ellipse, it became possible to deduce the infinity of the universe in accordance with physical regularity (Warburg [1925] 189-190).

Warburg places Kepler at the transition between the Renaissance and the Modern World, between astrology and astronomy (though this separation did not definitively eradicate the astrological knowledge, which became popular and persists to this day). Warburg highlights the fact that the astronomer, despite having also engaged in magical astrological practices (Kepler continued throughout his life to create predictions and horoscopes), was nevertheless the first to assert the importance of arithmetic in the study of the universe.

Thus, the attempt to resolve the phenomenon of astrology—which, according to Warburg, gravitates at the end of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance between two poles, the mathematical-numerical principle on one side, and the magical-ritual-imagistic principle on the other—receives, through Kepler’s work, renewed strength originating from the first pole (the mathematical-numerical). This shift lays the foundation for the development of modern science. Occurring in the early years of the seventeenth century, it marks the transition from the Renaissance (a transitional period, as Warburg sees it) toward the Modern World.

Warburg and Lévy-Brühl

The parallels between the concepts employed by Aby Warburg to understand the stages of astrological knowledge from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era, and the notions developed by Lucien Lévy-Brühl in building the opposition between European and primitive mentalities are significant. In Lévy-Brühl’s framework, mystical abstraction (focused on elements that establish links between visible and tangible objects and the invisible and hidden forces circulating within everything, endowing objects and beings with mystical properties and powers) is opposite to the laws of logic constructed by Western (European) thought and science. In Warburg’s analysis, mathematical abstraction, developed by the thought in the modern era, is opposed to the ties of veneration present in medieval astrological practices, from which the relationship between man and the cosmos follows the concept of the “law of participation”—a notion borrowed precisely from Lévy-Brühl’s anthropology.

As previously mentioned, prior to preparation of the 1925 lecture on the Sphaera barbarica, Warburg was certainly already engaged with the work of Lucien Lévy-Brühl and, consequently, with the concept of the loi de participation developed by the French anthropologist. In the notes for his lecture of April 1923, Bilder aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo-Indianer in Nord-Amerika, in the Introduction, Warburg alludes to Lévy-Brühl’s concept when mentioning the magical practices of the Pueblo Indians:

What interested me as a cultural historian was that in the midst of a country that had made technological culture into an admirable precision weapon in the hands of intellectual man, an enclave of primitive pagan humanity was able to maintain itself and—an entirely sober struggle for existence notwithstanding—to engage in hunting and agriculture with an unshakable adherence to magical practices that we are accustomed to condemning as a mere symptom of a completely backward humanity. Here, however, what we would call superstition goes hand in hand with livelihood. It consists of a religious devotion to natural phenomena, to animals and plants, to which the Indians attribute active souls, which they believe they can influence primarily through their masked dances. To us, this synchrony of fantastic magic and sober purposiveness appears as a symptom of a cleavage; for the Indian this is not schizoid but, rather, a liberating experience of the boundless communicability between man and environment (Warburg [1923] 1995, 2).

As observed in this passage, Warburg establishes an opposition between American culture and that of the Pueblo Indians, analogous to the one proposed by Lévy-Brühl between European and primitive mentalities. Warburg attributes to the Pueblo the cosmology in which the principle of magic structures their worldview. Later, referring to the symbolism of the ladder in Zuñi culture as an elevation of the walking man, as a reference to ascending and descending in space, he states:

The Zuñis have implemented with such artistry this harmonic system for organization in the cosmos that it rivals with the cosmological doctrine of superstition inherited from Hellenism. Thus, the correlation between man, plant, animal, and the cardinal points remains arbitrary and purely totemic (loosely translated from Warburg [1923] 2010a, 537 and Warburg [1923] 2015a, 217).

Although Warburg immediately references Ernst Cassirer’s book, Die Begriffsform im mythischen Denken (Cassirer 1922), a scholar with whom he had established a dialogue after the final period of his admission to the Kreuzlingen clinic, the reference to Hellenistic cosmology points toward the issue he would address two years later in his lecture on the Sphaera barbarica. In other words, the notion of a “cosmological doctrine of superstition” aligns with Lévy-Brühl’s concept of the loi de participation, in which the process of connection imposes itself on the relationship between man and the cosmos, building the sphere of magical causality, previously discussed. Furthermore, the mention of Hellenism here already expands the notion of primitive mentality to the realm of Late Antique cosmology, corroborating our assertion regarding the importance of Lucien Lévy-Brühl’s thought in the Warburgian conception of astrology in the Western tradition as a tool for orienting humanity within the cosmos. All of this points towards the interpretative unity that permeates Aby Warburg’s work.

In the other text also written in 1923, centered on the theme of his journey to the United States, the notes for the Kreuzlingen lecture, Warburg guides the idea of the previously called “cosmological doctrine of superstition” as a principle encompassing humanity across all eras. Thus, “participation”, while opposing the mentality of the modern European, exists as an underlying principle of man, manifesting in the very act of object manipulation. The creation of objects, therefore, represents the extension of the Self beyond the physical limits of the human body, encompassing the product of manipulation within a sphere of magical connection between subject and object:

The point of departure is this: I see man as an animal that handles and manipulates and whose activity consists in putting together and taking apart. That is how he loses his organic ego-feeling, specifically because the hand allows him to take hold of material things that have no nerve apparatus, since they are inorganic, but that, despite this, extend his ego inorganically. That is the tragic aspect of man, who, in handling and manipulating things, steps beyond his organic bounds (Warburg [1923] [1999] 2004, 312).

This theme would be revisited by Warburg in the introduction to Mnemosyne, in 1929, where it becomes one of the central motifs of the text. When he asserts that “the conscious creation of distance between oneself and the external world […] becomes the basis of artistic production” (Warburg [1929] [2009] 2017, 12), or that “the artist oscillating between the religious and the mathematical world view” (Warburg [1929] [2009] 2017, 12), Warburg is conceiving the domain of art within the pre-linguistic interval of human experience, located between the emotional upheaval caused by fundamental human feelings—such as pain, death, and love—and the impulse to represent them through images, transforming them into symbols.

In the case of Lucien Lévy-Brühl, the view of primitive mentality as an underlying element of European mentality would be developed in the anthropologist’s later writings, specifically in the unfinished notes posthumously published as Carnets. Here, in an entry dated August 31, 1938, Lévy-Brühl acknowledges a new course in his concept of “primitive mentality”, stating:

That participation did not belong exclusively to the primitive mentality but held also a place in our own, or, if one prefers, that the primitive mentality is in reality an aspect, a condition of human mentality in general (Lévy-Brühl [1938] [1949] 1975).

These notes, however, were written too late for Aby Warburg to respond to the development of Lévy-Brühl’s thought in its final phase.

*We are grateful to Maurizio Ghelardi, who, during an important period of academic collaboration, provided access to Aby Warburg’s manuscripts, from which the Brazilian version used here was edited, and who also wrote the Foreword to Presença do Antigo. This Brazilian version is a translation of the original German (handwritten or typed), compared with some texts contained in the Italian translation by Maurizio Ghelardi: AWO I.1 and AWO I.2. The excerpts cited from Aby Warburg’s writings about his trip to the United States (1895-1896) were taken directly from the Brazilian edition and then translated into English: História de fantasma (see also the important edition of the notes, edited in Italian by Maurizio Ghelardi: Warburg [1923] 2021).

Bibliography

Abbreviations

- AWO I.1

A. Warburg, La rinascita del paganesimo antico e altri scritti (1889-1914), a cura di M. Ghelardi, S. Müller, Torino 2004. - AWO I.2

A. Warburg, La rinascita del paganesimo antico e altri scritti (1917-1929), a cura di M. Ghelardi, Torino 2007. - AWM II

A. Warburg, Fra antropologia e storia dell’arte. Saggi, conferenze e frammenti, a cura di M. Ghelardi, Torino 2021. - História de fantasma

Histórias de fantasma para gente grande: escritos, esboços e conferências, São Paulo 2015 - Presença do Antigo

A. Warburg, A Presença do Antigo. Escritos inéditos, org. Cássio Fernandes, prefácio M. Ghelardi, Campinas 2018. - WEB

A. Warburg, Werke in einem Band. Auf der Grundlage der Manuskripte und Handexemplare, hrsg. und kommentiert von M. Treml, S. Weigel, P. Ladwig, Berlin 2010.

Bibliographical Refereces

- Belting 2001

H. Belting, Bild-Anthropologie. Entwürfe für eine Bildwissenschaft, München 2001. - Belting 2005

H. Belting, Por uma antropologia da arte, “Concinnitas” 6, 1, 8 (julho 2005), 65-78. - Cassirer 1922

E. Cassirer, Die Begriffsform im mythischen Denken, Leipzig 1922. - De Laude, Ferrando 2023

S. De Laude, M. Ferrando (a cura di), 21 aprile 1923. Il rituale del serpente, numero monografico, “La Rivista di Engramma” 201 (aprile 2023). - Durkheim 1895

E. Durkheim, Les Règles de la méthode sociologique, Paris 1895. - Freedberg 2008

D. Freedberg, Antropologia e storia dall’arte: la fine delle discipline?, “Rivista di Storia dell’Arte” 94 (2008), 5-18. - Goldman 1994

M. Goldman, Razão e diferença: Afetividade, racionalidade e relativismo no pensamento de Lévy-Bruhl, Rio de Janeiro 1994. - Lévy-Brühl 1910

L. Lévy-Brühl, Les Fonctions Mentales dans les Sociétés Inférieures, Paris 1910. - Lévy-Brühl 1922

L. Lévy-Brühl, La mentalité primitive, Paris 1922. - Lévy-Brühl [1938] [1949] 1975

L. Lévy-Bruhl, The Notebooks on Primitive Mentality [Carnets, Paris 1949], edited by M. Leenhardt, Eng. trans. by P. Riviere, Oxford 1975. - de Oliveira 2002

R.C. de Oliveira, Razão e Afetividade: o pensamento de Lucien Lévy-Brühl, Brasília 2002. - Saxl [1930] [1957] 2023

F. Saxl, Warburg’s Visit to New Mexico [Warburgs Besuch in Neu-Mexico], in Id., Lectures, London 1957, 325-330; ora in “La Rivista di Engramma” 201 (aprile 2023), 183-190. - Severi 2003

C. Severi, Warburg anthropologue ou le déchiffrement d’une utopie. De la biologie des images à l’anthropologie de la memoire, “L’Homme. Revue française d’anthropologie” 165 (2003), 78-79. - Villari 2014

E. Villari, Aby Warburg, antropologo dell’immagine, Roma 2014. - Warburg 1922

A. Warburg, Italienische Kunst und internationale Astrologie im Palazzo Schifanoia zu Ferrara, “L’Italia e l’Arte straniera. Atti del X Congresso Internazionale di Storia dell’Arte, 1912”, Roma 1922, 179-193. - Warburg [1923] 1995

A. Warburg, Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America [Bilder aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo-Indianer in Nord-Amerika, WIA III 93], Eng. trans. M.P. Steinberg, Ithaca 1995. - Warburg [1923] 2010a

A. Warburg, Bilder aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo-Indianer in Nord-Amerika [WIA III 93], in WEB, 524-566. - Warburg [1923] 2015a

A. Warburg, Imagens da região dos índios Pueblos na América do Norte [Bilder aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo-Indianer in Nord-Amerika, WIA III 93], in História de fantasma, 151-195. - Warburg [1923] [1999] 2004

A. Warburg, Memories of a Journey through the Pueblo Region [Reise-Erinnerungen aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo Indianer in Nordamerika, WIA III 93.4], trans. by S. Hawkes, in P. Michaud, Aby Warburg and the Image in Motion [Aby Warburg et l’image en mouvement, Paris 1999], New York 2004, 293-330. - Warburg [1923] 2021

A. Warburg, Ricordi di viaggio dal territorio degli indiani Pueblo nell’America settentrionale [Reise-Erinnerungen aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo Indianer in Nordamerika, WIA III 93.4], in AWM II, 166-190. - Warburg [1925] 2018

A. Warburg, A influência da Sphaera barbarica nas tentativas de ordenação cósmica do Ocidente [Die Einwirkung der Sphaera Barbarica auf die kosmischen Orientierungsversuche: Franz Boll zum Gedächtnis, WIA III 94.2.1], in Presença do Antigo, vol. 1, 141-196. - Warburg [1929] [2009] 2017

A. Warburg, Mnemosyne Atlas. Introduction [Einleitung, WIA III.102.3-4], Eng. trans. M. Rampley, “Art in Translation” 1/2 (March 2009), 273-283; ora in “La Rivista di Engramma” 142 (febbraio 2017), 11-29.

Abstract

Aby Warburg maintained an intellectual dialogue with anthropology, which had recently emerged as an autonomous discipline, as well as with some prominent anthropologists who were active between the late nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century. Particularly emblematic in this regard is the connection he established with the work of the French anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Brühl (1857-1939).

keywords | Aby Warburg; Lévy-Brühl; Art history; Anthropology.

La Redazione di Engramma è grata ai colleghi – amici e studiosi – che, seguendo la procedura peer review a doppio cieco, hanno sottoposto a lettura, revisione e giudizio questo saggio

(v. Albo dei referee di Engramma)

Per citare questo articolo / To cite this article: C. Fernandes, Partecipation and Creation of Distance. Aby Warburg and Lucien Lévy-Brühl, “La Rivista di Engramma” 227 (settembre 2025), pp. 225-236 | PDF